Collapse of the Golden State Freeway | |

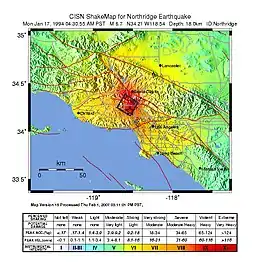

ShakeMap for the event created by the United States Geological Survey | |

Los Angeles Las Vegas San Diego Turlock | |

| UTC time | 1994-01-17 12:30:55 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 189275 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | January 17, 1994 |

| Local time | 4:30:55 a.m. PST[1] |

| Duration | 10–20 seconds[2] |

| Magnitude | 6.7 Mw[3] |

| Depth | 11.31 mi (18.20 km) |

| Epicenter | 34°12′47″N 118°32′13″W / 34.213°N 118.537°W |

| Fault | Northridge Blind Thrust Fault[4] |

| Type | Blind thrust |

| Areas affected | Greater Los Angeles Area Southern California United States |

| Total damage | $13–50 billion[5] (equivalent to $24–93 billion in 2021) |

| Max. intensity | IX (Violent)[1] |

| Peak acceleration | 1.82 g[6] |

| Peak velocity | 183 cm/s[7] |

| Casualties | 57 killed > 8,700 injured |

The 1994 Northridge earthquake was a moment magnitude 6.7 (Mw),[8] blind thrust earthquake that occurred on January 17, 1994, at 4:30:55 a.m. PST in the San Fernando Valley region of the City of Los Angeles. The quake had a duration of approximately 10–20 seconds, and its peak ground acceleration of 1.82 g was the highest ever instrumentally recorded in an urban area in North America.[9][10][11] Shaking was felt as far away as San Diego, Turlock, Las Vegas, Richfield, Phoenix, and Ensenada.[12] The peak ground velocity at the Rinaldi Receiving Station was 183 cm/s (4.1 mph; 6.6 km/h), the fastest ever recorded.[7]

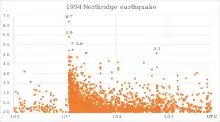

Two 6.0 Mw aftershocks followed, the first about one minute after the initial event and the second approximately 11 hours later, the strongest of several thousand aftershocks in all.[13] The death toll was 57, with more than 9,000 injured.[14][15] In addition, property damage was estimated to be $13–50 billion (equivalent to $24–93 billion in 2021), making it among the costliest natural disasters in U.S. history.[16]

Epicenter

The earthquake struck in the San Fernando Valley about 20 miles (32 km) northwest of downtown Los Angeles. Although given the name "Northridge", where the quake was believed to have been centered and substantial damage occurred, the actual epicenter was pinpointed in the neighboring community of Reseda within several days.

The United States Geological Survey placed the hypocenter's geographical coordinates at 34°12′47″N 118°32′13″W / 34.213°N 118.537°W and at a depth of 11.31 mi (18.20 km).[17] It occurred on a previously undiscovered fault, now named the Northridge Blind Thrust Fault (also known as the Pico Thrust Fault).[4] Several other faults experienced minor rupture during the main shock and other ruptures occurred during large aftershocks, or triggered events.[18]

Damage and fatalities

by the earthquake

Damage occurred up to 85 miles (137 km) away, with the most damage in the west San Fernando Valley, and the cities and neighborhoods of Santa Monica, Hollywood, Simi Valley, and Santa Clarita. The Historic Egyptian Theater in Hollywood was red-tagged and closed as was the Capital Theater in Glendale due to structural damage. The exact number of fatalities is unknown, with sources estimating the number to be 60[1][15] or "over 60",[19] to 72,[14] where most estimates fall around 60.[20] The "official" death toll was placed at 57;[14] 33 people died immediately or within a few days from injuries sustained,[21] and many died from indirect causes, such as stress-induced cardiac events.[22][23] Some counts factor in related events such as a man's suicide possibly inspired by the loss of his business in the disaster.[14] More than 8,700 were injured including 1,600 who required hospitalization.[24] Actress Iris Adrian died in September 1994 from complications of a broken hip she suffered in the earthquake.[25]

Sixteen people were killed as a result of the collapse of the Northridge Meadows apartment complex.[26] The Northridge Fashion Center and California State University, Northridge also sustained very heavy damage – most notably the collapse of parking structures. The earthquake also gained worldwide attention because of damage to the vast freeway network, which serves millions of commuters every day. The most notable was to the Santa Monica Freeway, Interstate 10, known as the busiest freeway in the United States, congesting nearby surface roads for three months while the freeway was repaired. Farther north, the Newhall Pass interchange of Interstate 5 (the Golden State Freeway) and State Route 14 (the Antelope Valley Freeway) collapsed as it had 23 years earlier in the 1971 Sylmar earthquake, even though it had been rebuilt with minor improvements to the structural components.[27] LAPD motorcycle officer Clarence Wayne Dean died because of the collapse of the Newhall Pass interchange, falling 40 feet from the damaged connector from southbound 14 to southbound I-5. He likely did not realize until too late in the early morning darkness that the elevated roadway had collapsed. The rebuilt interchange was renamed in his honor a year later.[28]

Additional damage occurred about 50 miles (80 km) southeast in the city of Anaheim, located in Orange County, as the scoreboard at Anaheim Stadium collapsed onto several hundred seats.[29] The stadium was vacant at the time. Although several commercial buildings also collapsed, loss of life was minimized because of the early morning hour of the quake, and because it also occurred on a federal holiday (Martin Luther King Jr. Day). Also, because of known seismic activity in California, area building codes dictate that buildings incorporate structural design intended to withstand earthquakes. However, the damage revealed that some structural specifications did not perform as intended. Because of these revelations, building codes were revised. Some structures were not red-tagged until months later because the damage was not immediately evident.

The quake produced unusually strong ground accelerations in the range of 1.0 g. Damage was also caused by fire and landslides. The Northridge earthquake was notable for hitting almost the same exact area as the Mw 6.6 San Fernando (Sylmar) earthquake. Estimates of total damage range between $13 and $50 billion.[30][31]

Most casualties and damage occurred in multi-story wood-frame buildings (such as the three-story Northridge Meadows apartment building). In particular, buildings with an unstable first floor (such as those with parking areas on the bottom) performed poorly.[32] Numerous fires were also caused by broken gas lines from houses shifting off their foundations or unsecured water heaters tumbling.[33] In the San Fernando Valley, several underground gas and water lines were severed, resulting in some streets experiencing simultaneous fires and floods. Damage to the system resulted in water pressure dropping to zero in some areas; this predictably affected success in fighting subsequent fires. Five days later, it was estimated that between 40,000 and 60,000 customers were still without public water service.[34] As expected, unreinforced masonry buildings and houses on steep slopes suffered damage. However, school buildings (K-12), which are required by California law to be reinforced, in general survived fairly well.

Valley fever outbreak

An unusual effect of the Northridge earthquake was an outbreak of coccidioidomycosis (Valley fever) in Ventura County. This respiratory disease is caused by inhaling airborne spores of the fungus. The 203 cases reported, of which three resulted in fatalities, constituted roughly 10 times the normal rate in the initial eight weeks. This was the first report of such an outbreak following an earthquake, and it is believed that the spores were carried in large clouds of dust created by seismically triggered landslides.[35] Most of the cases occurred immediately downwind of the landslides.[36]

Facilities and infrastructure affected

Hospitals

Eleven hospitals suffered structural damage and were damaged or rendered unusable.[24] Not only were they unable to serve their local neighborhoods, but they also had to transfer out their inpatient populations, which further increased the burden on nearby hospitals that were still operational. As a result, the state legislature passed a law requiring all hospitals in California to ensure that their acute care units and emergency rooms would be in earthquake-resistant buildings by January 1, 2005. Most were unable to meet this deadline and only managed to achieve compliance in 2008 or 2009.[37]

Television, movie, and music productions

The production of movies and TV shows was disrupted. At the time of the quake, before dawn on Monday morning, the Warner Bros. film Murder in the First (with Christian Slater, Kevin Bacon, and Gary Oldman) was being filmed only four miles (6.4 km) from the epicenter. Production came to a halt. The main courtroom set was in shambles. The building containing the set was later "red tagged" as unsafe due to the damage it sustained. The Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode "Profit and Loss" was being filmed at the time, and actors Armin Shimerman and Edward Wiley left the Paramount Pictures lot in full Ferengi and Cardassian makeup, respectively.[38] The season five episode of Seinfeld entitled "The Pie" was due to begin shooting on January 17 before stage sets were damaged. Also, ABC's General Hospital set at ABC Television Center suffered partial structural collapse and water damage.

All of the earthquake sequences in the Wes Craven film New Nightmare were filmed a month prior to the Northridge quake. The real quake struck only weeks before filming was completed. Subsequently, a team was sent out to film footage of the quake-damaged areas of the city. The cast and crew had initially thought that the scenes that were filmed before the real quake struck were a bit overdone, but upon viewing the footage after the earthquake, they were reportedly startled by the realism of it.[39]

Some archives of film and entertainment programming were also affected. For example, the original 35 mm master films for the 1960s sitcom My Living Doll were destroyed.[40]

Transportation

Portions of a number of major roads and freeways, including Interstate 10 over La Cienega Boulevard, and the interchanges of Interstate 5 with California State Route 14, 118, and Interstate 210, were closed because of structural failure or collapse.[41][42] James E. Roberts was chief bridge engineer with Caltrans and was placed in charge of the seismic retrofit program for Caltrans until his death in 2006.

Rail service was briefly interrupted, with full Amtrak and expanded Metrolink service resuming in stages in the days after the quake. Interruptions to road transport caused Metrolink to experiment with service to Camarillo in February and Oxnard in April,[43][44] which continues today as the Ventura County Line, and extended the Antelope Valley Line almost ten years ahead of schedule. Six new stations opened in six weeks.[45] Metrolink leased equipment from Amtrak, San Francisco's Caltrain, and Toronto, Canada's GO Transit to handle the sudden onslaught of passengers. Amtrak ceased service in the Pasadena Subdivision following structural damage to a rail bridge in Arcadia and redirected all rail traffic through Riverside and Fullerton.[46] All MTA bus lines operated service with detours and delays on the day of the quake. Los Angeles International Airport and other airports in the area were also shut down as a 2-hour precaution, including Burbank-Glendale-Pasadena Airport (now Hollywood Burbank Airport) and Van Nuys Airport, which is near the epicenter, where the control tower suffered from radar failure and panel collapse. The airport was reopened in stages after the quake.

California State University, Northridge

California State University, Northridge, was the closest university to the epicenter. Many campus buildings were heavily damaged and a parking structure collapsed. Many classes were moved to temporary structures.[47] The 1994 Northridge earthquake greatly affected the CSUN campus, damaging much of its infrastructure, and causing multiple fires and explosions throughout the campus.[48] The magnitude 6.7 earthquake damaged several buildings as well as destroying all communications, such as telephone lines and causing computer systems to shut down. The seismic event killed two CSUN students at the Northridge Meadows Complex along with 14 other residents.[49] The damage caused a shutdown of the campus and delayed the start of the 1994 Spring semester.

Campus damage

All 58 buildings on campus sustained significant damage, resulting in a $406 million recovery effort (equivalent to $757 million today).[50] In addition, the newly completed student parking structure C collapsed, and had to be demolished. The Oviatt Library experienced both interior and exterior damage, but the overall frame of the central part of the building remained stable, allowing student use to continue.[51] In the Science Complex, Building #1 and #2 suffered fire damage while the bridges connecting buildings #3 and #4 were closed and named unstable.[52] The Fine Arts Building and the South Library experienced internal structural damage, resulting in the demolition and replacement of both buildings.

Classes and enrollment

The 1994 Spring semester was delayed by two weeks due to the Northridge earthquake. The campus was unable to use any of its classrooms because of the damage the buildings sustained. The campus still opened and provided students with mobile classrooms and mobile offices. CSUN President Dr. Blenda Wilson assured the rental of temporary structures to be placed in available spaces throughout the campus. An estimated $350 million (equivalent to $690 million today) was used to supply the number of trailers and domes which housed classes and administration offices. Enrollment dropped by approximately 1,000 students, leaving some homeless as dormitories were closed due to damage that rendered them unsafe and which required repair.[53]

External resources

The seismic event led to millions of dollars worth of damage resulting in a sharp drop in student enrollment. CSUN received financial assistance for its efforts in reestablishing the damaged buildings with monetary gifts from the McCarthy Foundation, the Common Wealth Fund, and the Union Bank Foundation. In addition, the campus received a $23,000 check (equivalent to $45,000 today) from the Los Angeles Times Valley Edition for the journalism department.[54] CSUN also received assistance from government agencies FEMA and OES to support the recovery effort and serve the needs of the local community.[55] UCLA and Pierce College opened their doors and allowed CSUN students to use their libraries while providing shuttle buses to and from the university.

Entertainment and sports

Universal Studios Hollywood shut down the Earthquake attraction, based on the 1974 motion picture blockbuster, Earthquake. It was closed for the second time since the Loma Prieta earthquake. Angel Stadium of Anaheim (then known as Anaheim Stadium) suffered some damage when the scoreboard fell into the seats,[29] forcing a Mickey Thompson Entertainment Group off-road race at the ballpark to be postponed from that upcoming weekend to February 12.[56]

Other buildings

Numerous Los Angeles museums, including the Art Deco Building in Hollywood, were closed, as were numerous city shopping malls. Gazzarri's nightclub suffered irreparable damage and had to be torn down. The city of Santa Monica suffered significant damage. Many multifamily apartment buildings in Santa Monica were yellow-tagged and red-tagged. An especially hard hit area was between Santa Monica Canyon and Saint John's Hospital, a linear corridor that suffered a significant amount of property damage. The City of Santa Monica provided assistance to landlords dealing with repairs so tenants could return home as soon as possible. In Valencia, the California Institute of the Arts experienced heavy damage, with classes relocated to a nearby Lockheed test facility for the remainder of 1994. The Los Angeles Unified School District closed local schools throughout the area, which reopened one week later. UCLA and other local universities were also shut down. The University of Southern California suffered some structural damage to several older campus buildings, but classes were conducted as scheduled.

Aftermath

Lifestyle disruptions in the weeks following

In the weeks following the quake, many San Fernando Valley residents had either lost their homes entirely or experienced structural damage too severe to continue living in them without making repairs. Although the vast majority of homes in the area, with the exception of a few particular neighborhoods, were relatively unaffected; many feared an aftershock to rival or exceed the severity of the first one. While a notable aftershock never came, many residents opted to stay in shelters or live with friends and family outside the area for a short time following.[57]

While many businesses remained closed in the days following the quake, some infrastructure was not able to be rebuilt for months, even years later. The daily commute for many drivers in the weeks following was significantly lengthened, notably for those traveling between Santa Clarita and Los Angeles, and commuters on I-10 traveling to and from the Westside. Additionally, many businesses were forced to relocate or use temporary facilities in order to accommodate structural damage to their original locations or the difficulty accessing them. Some people even made temporary relocations closer to their jobs while their homes or neighborhoods were being rebuilt.

State legislative response

The Northridge earthquake led to a number of legislative changes. Due to the large amount lost by insurance companies, most insurance companies either stopped offering or severely restricted earthquake insurance in California. In response, the California Legislature created the California Earthquake Authority (CEA), which is a publicly managed but privately funded organization that offers minimal coverage.[58] A substantial effort was also made to reinforce freeway bridges against seismic shaking, and a law requiring water heaters to be properly strapped was passed in 1995.

Engineering analysis

The analysis of the effect of Northridge earthquake on behavior of structures has been investigated by many researchers. For example, the behavior of underground walls has been evaluated for the Northridge earthquake using numerical methods. The comparison of the seismic behavior of underground braced walls with ACI 318 design method reveals that bending moment and shear force of the walls under Northridge earthquake loads were observed to reach 2.8 and 2.7 times as large as the respective allowable limits. Therefore, caution should be taken in seismic design of diaphragm walls using ACI 318 code requirements.[59]

In popular culture

- The Northridge Earthquake was the subject of the 1995 film Epicenter U., a first-hand account of healing from the natural disaster, directed by Alexis Krasilovsky.[60][61][62][63][64][65][66] The Earthquake Haggadah (1995) was a video excerpt from Epicenter U. narrated by Wanda Coleman. Distributed in 3/4" and VHS by the Poetry Film Workshop circa 1998. Re-released as part of the DVD Some Women Writers Kill Themselves in 2008.

- The Northridge earthquake was used as a plot device in the 2004 film A Cinderella Story. The film is a modern retelling of the Cinderella classic starring Hilary Duff and Chad Michael Murray. In it, Duff's character, Sam Montgomery, lives in the San Fernando Valley with her father, stepmother, and two stepsisters. Her father, Hal, perishes in the quake trying to save her stepmother, setting the story in motion.[67]

- A song about the earthquake, set to the tune of "Happy Farmer", was featured in the Animaniacs episode "A Quake, A Quake!".[68]

- Simon Harris and Daddy Freddy recorded The Big One, a song "dedicated to all the victims"[69] that references the magnitude and events of the quake. Its glib treatment of the subject and ironically named label of release (Harris' Music of Life) has led some to believe the two didn't like Los Angeles and were, in reality, less than concerned about the event.

- The Northridge Earthquake was mentioned in the 1997 film Volcano.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Historic Earthquakes". Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Introduction". Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ↑ ANSS: Northridge 1994 .

- 1 2 "USGS Northridge Earthquake 10th Anniversary". Archived from the original on December 2, 2003. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ↑ "1994 Quake Still Fresh in Los Angeles Minds". Los Angeles Daily News. January 11, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- ↑ Yegian, M.K.; Ghahraman; Gazetas, G.; Dakoulas, P.; Makris, N. (April 1995). "The Northridge Earthquake of 1994: Ground Motions and Geotechnical Aspects" (PDF). Third International Conference on Recent Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics. Northeastern University College of Engineering. p. 1384. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 6, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- 1 2 "ShakeMap Scientific Background". Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ↑ ANSS. "Northridge 1994: 6.7 – 1km NNW of Reseda, CA". Comprehensive Catalog. U.S. Geological Survey.

- ↑ Luco, Nicolas (2019). "Seismic design and hazard maps: Before and after". Structure: 28–30.

- ↑ USGS Earthquake Information for 1994 "Significant Earthquakes of the World 1994" Archived 2011-07-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Northridge EarthquakeArchived 2004-09-04 at the Wayback Machine Southern California Earthquake Data Center. Retrieved October 6, 2006.

- ↑ "M 6.7 - Northridge - Impact". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- ↑ Douglas Dreger. "The Large Aftershocks of the Northridge Earthquake and their Relationship to Mainshock Slip and Fault Zone Complexity". Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Reich, K. Study raises Northridge quake death toll to 72. Los Angeles Times December 20, 1995

- 1 2 Miller, Devon (January 17, 2021). "Remembering The Northridge Earthquake 27 Years Later". The Valley Post. Archived from the original on May 25, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ↑ "1994 Quake Still Fresh in Los Angeles Minds". Los Angeles Daily News. January 11, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ↑ "M 6.7 - 1km NNW of Reseda, CA". Earthquake Hazards Program. USGS. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ↑ "Southern California Earthquake Data Center". Caltech. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ↑ "FEMA". Archived from the original on March 15, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ↑ "History Channel". Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ↑ Peek-Asa, C.; et al. (1998). "Fatal and hospitalized injuries resulting from the 1994 Northridge earthquake". International Journal of Epidemiology. 27 (3): 459–465. doi:10.1093/ije/27.3.459. PMID 9698136.

- ↑ Kloner, R. A.; et al. (1997). "Population-Based Analysis of the Effect of the Northridge Earthquake on Cardiac Death in Los Angeles County, California". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 30 (5): 1174–1180. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00281-7. PMID 9350911.

- ↑ Leor, J.; et al. (1996). "Sudden cardiac death triggered by an earthquake". New England Journal of Medicine. 334 (4): 413–419. doi:10.1056/NEJM199602153340701. PMID 8552142.

- 1 2 "Executive Summary". Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved June 8, 2007.

- ↑ "Obituary: Iris Adrian". The Independent. October 23, 2011. Archived from the original on May 1, 2022.

- ↑ "25 Years Later: The Desperate Search for Survivors at Northridge Meadows Apartments" (with video). NBC News Los Angeles. January 18, 2019 [January 15, 2019].

- ↑ "Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology". Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on April 3, 2006. Retrieved March 25, 2006.

- ↑ "Interchange Named for Officer Who Died in Quake". Los Angeles Times. July 8, 1994.

- 1 2 Spencer, Terry (January 18, 1994). "Earthquake: Disaster Before Dawn: Scoreboard Crashes Onto Seats in Anaheim Stadium: Collapse: The 17.5-ton Sony 'Jumbotron' also destroyed a section of roof as it broke loose and fell to the left-field upper deck". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "1994 Quake Still Fresh in Los Angeles Minds". Los Angeles Daily News. January 11, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Comments for the Significant Earthquake". National Geophysical Data Center. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ↑ Schleuss, Jon; Lin, Rong-Gong II (November 22, 2019). "Dangerous L.A. apartment buildings most at risk in an earthquake are quickly being fixed". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "Secure Your Stuff: Water Heater". Archived from the original on May 3, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2007.

- ↑ Scawthorn; Eidinger; Schiff, eds. (2005). Fire Following Earthquake. Reston, VA: ASCE, NFPA. ISBN 978-0-7844-0739-4. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ↑ Schneider, E., Hajjeh, R. A., Der Spiegel, R. A., Jibson, R. W., Harp, E. L., Marshall, G. A., . . . Werner, S. B. (1997). A coccidioidomycosis outbreak following the Northridge, Calif, earthquake. Jama, 277(11), 904-908.

- ↑ "Coccidioidomycosis Outbreak". USGS Landslide Hazards Program. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014.

- ↑ Cheevers, Jack; Abrahamson, Alan (January 19, 1994), "Earthquake: The Long Road Back: Hospitals Strained to the Limit by Injured: Medical care: Doctors treat quake victims in parking lots. Details of some disaster-related deaths are released", Los Angeles Times

- ↑ Erdmann, Terry J.; Paula M. Block (2010). Star Trek: Deep Space Nine Companion. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-50106-8.

- ↑ "New Nightmare (1994)". IMDb. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ↑ Susan King, "The 'perfect' '60s woman", Los Angeles Times, April 4, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2012

- ↑ Weinraub, Bernard (January 18, 1994). "The Freeways; Collapsed Freeways Cripple City Where People Live Behind Wheel". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ↑ Taylor, Alan. "The Northridge Earthquake: 20 Years Ago Today – Info and images of collapsed freeways". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 25, 2019.

- ↑ Mitchell, J. E. (January 25, 1994). "Camarillo Gets a Little Good News: MetroLink Is Coming". Los Angeles Times. p. B6. Retrieved March 23, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Catania, Sara (April 4, 1994). "Last of Post-Quake Metrolink Stations Opening in Oxnard". Los Angeles Times. p. B5. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ↑ Gbenekama, Delana G. (October 2012). Metrolink 20th Anniversary Report (PDF). HWDS and Associates, Inc. pp. 9, 48. Retrieved May 21, 2018.

- ↑ Hymon, Steve (March 5, 2016). "Photos: Gold Line Foothill Extension's opening day". thesource.metro.net. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

- ↑ Chandler, John; Johnson, John-Us (February 15, 1994). "Quake-Ravaged CSUN Reopens Amid Confusion". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ↑ Heistand, Jesse (1994). "Science Complex Explodes". Daily Sundial.

- ↑ Saringo-Rodriguez, John (January 17, 2014). "20 Years after Northridge Earthquake, CSUN Is Not Just Back, Better". sundial.csun.edu.

- ↑ Moore, Solomon (1999). "Education: Three-story Monterey Hall and Five-story Administration Structure Are among Last Campus Construction Projects Related to the 1994 Earthquake". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Collins, Michael (March 1, 1994). "Temporary library may ease traveling headaches over hill". Daily Sundial.

- ↑ Heistand, Jesse (January 24, 1994). "Science Complex Explodes". Daily Sundial.

- ↑ Lebrun, Chris (February 24, 1994). "Slight Drop in CSUN Enrollment Attributed to Quake". Daily Sundial.

- ↑ Kastle (March 1, 1994). "CSUN Grateful for Grants and Donations". Daily Sundial.

- ↑ Symes, Michael (March 1, 1994). "FEMA Opens CSUN Office". Daily Sundial.

- ↑ Shepard, Eric (January 19, 1994). "Trojan Game Moved: Earthquake: USC will play Arizona State at Lyon Center because of possible damage". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ↑ "The Northridge Earthquake: 20 Years Ago Today". The Atlantic. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- ↑ "CA Earthquake Authority". Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ↑ Bahrami, M.; Khodakarami, M.I.; Haddad, A. (April 2019). "Seismic behavior and design of strutted diaphragm walls in sand". Computers and Geotechnics. 108: 75–87. Bibcode:2019CGeot.108...75B. doi:10.1016/j.compgeo.2018.12.019. S2CID 128226913.

- ↑ "'Epicenter U.' Captures Earthquake Aftermath: Education: CSUN film students' work documents frustration, anxiety and hope that followed the devastating temblor". Los Angeles Times. October 5, 1994.

- ↑ Thesaurus - Geologic Time Terms. "News & Notes | Seismological Research Letters | GeoScienceWorld". Pubs.geoscienceworld.org. doi:10.1785/gssrl.66.5.5. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Pauly, Brett."Film Helps CSUN Remember," Daily News, L.A.. Life Section, February 16, 1995, p.11. g. Commendation Award from Richard J. Riordan, Mayor, Los Angeles

- ↑ Slater, Eric. "Student Cinema Verite Examines Earthquake," Los Angeles Times, Metropolitan Digest, October 11, 1994, p. B2.

- ↑ "Good Morning, America," clips from "Epicenter U.," with appearances by Prof. Krasilovsky and her film production students, Scott Jolgen and T.C. Warner, January 14, 1995.

- ↑ Commendation Award from Richard J. Riordan, Mayor, Los Angeles, California, February 14,1995

- ↑ "The Best of the Weekend," Los Angeles Times, Calendar Section, October 6, 1995, p.F1,2.

- ↑ Crust, Kevin (July 16, 2004). "Midnight can't come too soon". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 1, 2022.

- ↑ Elliot, Austin (January 21, 2013). "Yakko, Wakko, and Dot recount the Northridge quake". American Geophysical Union. Retrieved March 1, 2022.

- ↑ "Daddy Freddy - The Big One". YouTube. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

External links

- Southern California Earthquake Data Center

- USGS Pasadena Archived June 6, 2003, at the Wayback Machine

- USC Earthquake Engineering-Strong Motion Group

- SAC Steel Project (Study of welded steel failures)

- Helicopter Footage Filmed After The Quake

- City of Los Angeles Re-survey of the San Fernando Valley

- Film "Epicenter U."

- Film "Earthquake Haggadah, The"

- The International Seismological Centre has a bibliography and/or authoritative data for this event.