Nuri al-Said | |

|---|---|

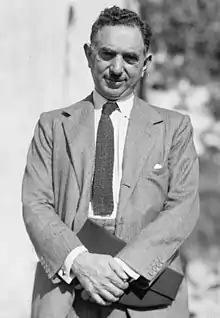

Nuri al-Said in 1936 | |

| Prime Minister of Iraq | |

| In office 3 March 1958 – 18 May 1958 | |

| Monarch | Faisal II |

| Preceded by | Abdul-Wahab Mirjan |

| Succeeded by | Ahmad Mukhtar Baban |

| In office 4 August 1954 – 20 June 1957 | |

| Monarch | Faisal II |

| Preceded by | Arshad al-Umari |

| Succeeded by | Ali Jawdat Al-Ayyubi |

| In office 15 September 1950 – 12 July 1952 | |

| Monarchs | Faisal II Prince ʻAbd al-Ilah (Regent) |

| Preceded by | Tawfiq al-Suwaidi |

| Succeeded by | Mustafa Mahmud al-Umari |

| In office 6 January 1949 – 10 December 1949 | |

| Monarchs | Faisal II Prince ʻAbd al-Ilah (Regent) |

| Preceded by | Muzahim al-Pachachi |

| Succeeded by | Ali Jawdat Al-Ayyubi |

| In office 21 November 1946 – 29 March 1947 | |

| Monarchs | Faisal II Prince ʻAbd al-Ilah (Regent) |

| Preceded by | Arshad al-Umari |

| Succeeded by | Salih Jabr |

| In office 10 October 1941 – 4 June 1944 | |

| Monarchs | Faisal II Prince ʻAbd al-Ilah (Regent) |

| Preceded by | Jamil al-Midfai |

| Succeeded by | Hamdi al-Pachachi |

| In office 25 December 1938 – 31 March 1940 | |

| Monarchs | Ghazi I Faisal II Prince ʻAbd al-Ilah (Regent) |

| Preceded by | Jamil al-Midfai |

| Succeeded by | Rashid Ali al-Gaylani |

| In office 23 March 1930 – 3 November 1932 | |

| Monarch | Faisal I |

| Preceded by | Naji al-Suwaydi |

| Succeeded by | Naji Shawkat |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Nuri Pasha al-Said December 1888 Baghdad, Baghdad Vilayet, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 15 July 1958 (aged 69) Baghdad, Arab Federation |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound |

| Political party | Covenant Party, Constitutional Union Party (Iraq) |

Nuri Pasha al-Said CH (Arabic: نوري السعيد; December 1888 – 15 July 1958) was an Iraqi politician during the Mandatory Iraq and the Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq. He held various key cabinet positions and served eight terms as the Prime Minister of Iraq.

From his first appointment as prime minister under the British Mandate in 1930, Nuri was a major political figure in Iraq under the monarchy. The 1930 Anglo-Iraqi Treaty granted Britain permanent military prerogatives in Iraq, but also paved the way for the country's nominal independence and entry as a member of the League of Nations in 1932. Nuri was forced to flee the country after the 1941 Iraqi coup d'état which brought a pro-Nazi government to power, but following a British-led intervention he was re-installed as prime minister.

During the early fifties, Nuri's government negotiated a fifty-fifty profit-sharing agreement on royalties with the Iraq Petroleum Company as oil began to play a significant role in the Iraqi economy. The agreement, along with the establishment of the Iraqi Development Board, provided for a series of ambitious schemes and projects to foster comprehensive economic growth in Iraq, and the private sector came to dominate the country's economic activity. However, the working conditions of the poor remained poorly addressed, which further contributed to the growth of anti-monarchist sentiment. The formation of the Baghdad Pact in 1955 exacerbated discontent in the country.

A controversial figure throughout most of his career, Nuri was deeply unpopular amongst several fragments of Iraqi society by the end of 1950s. His political views, regarded as a blend of Iraqi nationalism, conservatism, pro-western themes, anti-communism, and anti-nasserism, were believed by his detractors to have failed in adapting to the country's changed social circumstances. A coup d'état took place in July 1958 and led to the overthrow of the Hashemite monarchy. Nuri attempted to flee the country but was captured and killed.

Biography

Early career

He was born in Baghdad to middle class Sunni Muslim family of North Caucasian origin.[1] His father was a minor government accountant. Nuri graduated from a military college in Istanbul in 1906, trained at the staff college there in 1911 as an officer in the military of the Ottoman Empire and was among the officers dispatched to Ottoman Tripolitania in 1912 to resist the Italian occupation of that province. He was an elusive guerrilla leader, with Jaafar Al-Askari, against the British in Libya in 1915.[2]

After being captured and held prisoner by the British in Egypt, he and Jaafar were converted to the Arab nationalist cause and fought in the Arab Revolt under Emir Faisal ibn Hussain of the Hejaz, who would later reign briefly as King of Arab Syria before he was installed as King of Iraq. On one operation Nuri rode with T. E. Lawrence and his British Army driver as crew of a Rolls-Royce Armoured Car.[3]

Like other Iraqi officers who had served under Faisal, he went on to emerge as part of a new political elite.

Initial positions under Iraqi monarchy

Nuri headed the Arab troops who took Damascus for Faisal in the wake of the retreating Turkish forces in 1918. When Faisal was deposed by the French in 1920, Nuri followed the exiled monarch to Iraq, and in 1922 became first director general of the Iraqi police force. He used the position to fill the force with his placemen, a tactic that he would repeat in subsequent positions; that was a basis of his considerable political clout in later years.

He was a trusted ally of Faisal who, in 1924, appointed him deputy commander in chief of the army so as to ensure the loyalty of the troops to the regime. Once again, Nuri used the position to build up his own power base. During the 1920s, he supported the king's policy to build up the nascent state's armed forces, based on the loyalty of Sharifian officers, the former Ottoman soldiers who formed the backbone of the regime.

Prime Minister for first time

Faisal first proposed Nuri as prime minister in 1929, but it was only in 1930 that the British were persuaded to forgo their objections. As in previous appointments, Nuri was quick to appoint supporters to key government positions, but that only weakened the king's own base among the civil service, and the formerly close relationship between the two men soured. Among Nuri's first acts as prime minister was the signing of the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1930, an unpopular move since it essentially confirmed Britain's mandatory powers and gave them permanent military prerogatives in the country even after full independence was achieved. In 1932, he presented the Iraqi case for greater independence to the League of Nations.

In October 1932, Faisal dismissed Nuri as Prime Minister and replaced him with Naji Shawkat, which curbed Nuri's influence somewhat; after the death of Faisal the following year and the accession of Ghazi, his access to the palace decreased. Further impeding his influence was the rise of Yasin al-Hashimi, who would become prime minister for the first time in 1935. Nevertheless, Nuri continued to hold sway among the military establishment, and his position as a trusted ally of the British meant that he was never far from power. In 1933, the British persuaded Ghazi to appoint him foreign minister, a post he held until the Bakr Sidqi coup in 1936. However, his close ties to the British, which helped him remain in important positions of state, also destroyed any remaining popularity.

Intriguing with army

The Bakr Sidqi coup showed the extent to which Nuri had tied his fate to that of the British in Iraq: he was the only politician of the toppled government to seek refuge in the British Embassy, and his hosts sent him into exile in Egypt. He returned to Baghdad in August 1937 and began plotting his return to power in collaboration with Colonel Salah al-Din al-Sabbagh. That so perturbed Prime Minister Jamil al-Midfai that he persuaded the British that Nuri was a disruptive influence who would be better off abroad. They obliged by convincing Nuri to take up residence in London as the Iraqi ambassador. Despairing perhaps of his relationship with Ghazi, he now began to secretly suggest co-operation with the House of Saud.

Back in Baghdad in October 1938, Nuri re-established contact with al-Sabbagh, and persuaded him to overthrow the Midfai government. Al-Sabbagh and his cohorts launched their coup on 24 December 1938, and Nuri was reinstated as prime minister. He sought to sideline the king by promoting the position and possible succession of the latter's half-brother Prince Zaid. Simultaneously, the British were irritated by Ghazi's increasingly nationalistic broadcasts on his private radio station. In January 1939, the king further aggrieved Nuri by appointing Rashid Ali al-Gaylani head of the Royal Divan. Nuri's campaign against his rivals continued in March that year, when he claimed to have unmasked a plot to murder Ghazi and used it as an excuse to carry out a purge of the army's officer corps.

When Ghazi died in a car crash on 4 April 1939, Nuri was widely suspected of being implicated in his death. At the royal funeral crowds chanted, "You will answer for the blood of Ghazi, Nuri". He supported the accession of 'Abd al-Ilah as regent for Ghazi's successor, Faisal II, who was still a minor. The new regent was initially susceptible to Nuri's influence.

On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Soon, Germany and Britain were at war. In accordance with Article 4 of the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty, Iraq was committed to declaring war on Germany. Instead, in an effort to maintain a neutral position, Nuri announced that Iraqi armed forces would not be employed outside of Iraq. While German officials were deported, Iraq would not declare war.[4]

By then, affairs in Europe had begun to affect Iraq; the Battle of France in June 1940 encouraged some Arab nationalist elements to seek, in the style of the United States and Turkey, to move toward neutrality toward Germany and Italy rather than being part of the British war effort. While Nuri generally was more pro-British, al-Sabbagh moved into the camp more positively oriented toward Germany. The loss of his main military ally meant that Nuri "quickly lost his ability to affect events".[5]

Co-existence with regent in the 1940s

In April 1941, the pro-neutrality elements seized power, installing Rashid Ali al-Kaylani as prime minister. Nuri fled to British-controlled Transjordan; his protectors then sent him to Cairo, but after occupying Baghdad they brought him back, installing him as prime minister under the British occupation. He would retain the post for over two and half years, but from 1943 onward, the regent obtained a greater say in the selection of his ministers and began to assert greater independence. Iraq remained under British military occupation until late 1947. He served as the President of the Senate of Iraq from July 1945 to November 1946, and from 1948 to January 1949.[6]

The regent's brief flirtation with more liberal policies in 1947 did little to stave off the problems that the established order was facing. The social and economic structures of the country had changed considerably since the establishment of the monarchy, with an increased urban population, a rapidly growing middle class, and increasing political consciousness among the peasants and the working class, in which the Iraqi Communist Party was playing a growing role. However, the political elite, with its strong ties and shared interests with the dominant classes, was unable to take the radical steps that might have preserved the monarchy.[7] The attempt by the elite to retain power during the last ten years of the monarchy, Nuri rather than the regent would increasingly play the dominant role, thanks largely to his superior political skills.

Regime resists growing political unrest

In November 1946, an oil workers' strike culminated in a massacre of the strikers by the police, and Nuri was brought back as premier. He briefly brought the Liberals and National Democrats into the cabinet, but soon reverted to the more repressive approach he generally favoured, ordering the arrest of numerous communists in January 1947. Those captured included party secretary Fahd. Meanwhile, Britain attempted to legalise a permanent military presence in Iraq even beyond the terms of the 1930 treaty although it no longer had World War II to justify its continued presence there. Both Nuri and the regent increasingly saw their unpopular links with Great Britain as the best guarantee of their own position, and accordingly set about co-operating in the creation of a new Anglo-Iraqi Treaty. In early January 1948 Nuri himself joined the negotiating delegation in England, and on 15 January the treaty was signed.

The response on the streets of Baghdad was immediate and furious. After six years of British occupation, no single act could have been less popular than giving the British an even larger legal role in Iraq's affairs. Demonstrations broke out the following day, with students playing a prominent part and the Communist Party guiding much of the anti-government activity. The protests intensified over the following days, until the police fired on a mass demonstration (20 January), leaving many casualties. On the following days, 'Abd al-Ilah disavowed the new treaty. Nuri returned to Baghdad on 26 January and immediately implemented a harsh policy of repression against the protesters. At mass demonstration the next day, police fired again at the protesters, leaving many more dead. In his struggle to implement the treaty, Nuri had destroyed any credibility that he had left. He retained considerable power throughout the country, but he was generally hated.

He was determined to drive the Jews out of his country as quickly as possible,[8][9] and on 21 August 1950, he threatened to revoke the license of the company transporting the Jewish exodus if it did not fulfill its daily quota of 500 Jews. On 18 September 1950, Nuri summoned a representative of the Jewish community, claimed Israel was behind the emigration delay and threatened to "take them to the borders" and expel the Jews.

In 1950, Nuri Al-Said turned to building up Iraq's internal strength by concentrating on economic development. He replaced the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty (1948) with a new oil agreement with the Iraq Petroleum Company on the basis of 50/50 profit sharing, which increased the amount of funds available for development. This allowed for the establishment of the Development Board for reconstruction which launched a series of ambitious schemes and projects to foster comprehensive growth in Iraq. Private capital invested in industry amounted to about ID 4 million in 1953, rising to nearly ID 20 million by 1956, although the working conditions of the poor had hardly been assessed, which led to reprimand by the ever-growing anti-monarchist sentiment in Iraq.[10]

The next major political demarche with which Nuri's name would be associated was the Baghdad Pact, a series of agreements concluded between 1954 and 1955, which tied Iraq politically and militarily with the Western powers and their regional allies, notably Turkey. The pact was especially important to Nuri, as it was favoured by the British and Americans. On the other hand, it was also contrary to the political aspirations of most of the country. Taking advantage of the situation, Nuri stepped up his policies of political repression and censorship.

The political situation deteriorated in 1956, when Israel, France and Britain colluded in an invasion of Egypt, in response to the nationalisation of the Suez Canal by President Gamal Abdel Nasser. Nuri was overjoyed with the tripartite move and instructed the radio station to play The Postmen Complained about the Abundance of My Letters as a way to mock Nasser, whose father was a postal clerk. However, Nuri then publicly condemned the invasion, as the national sentiment was strongly for Egypt. The invasion exacerbated popular mistrust of the Baghdad Pact, and Nuri responded by refusing to sit with British representatives during a meeting of the Pact and cut off diplomatic relations with France. According to historian Adeeb Dawish, "Nuri's circumspect response hardly placated the seething populace."[11]

Mass protests and disturbances occurred throughout the country, in Baghdad, Basrah, Mosul, Kufa, Najaf and al-Hillah. In response Nuri decreed martial law and sent in troops to some southern cities to suppress the riots, while in Baghdad, nearly 400 protesters were detained. Nuri's political position was weakened, so much that he became more "discouraged and depressed" than ever before (according to the British ambassador) and was genuinely fearful that he would be unable to restore stability.[11] Meanwhile, the opposition began to co-ordinate its activities: in February 1957, a Front of National Union was established, bringing together the National Democrats, the Independents, the Communists, and the Ba'th Party. A similar process within the military officer corps followed, with the formation of the Supreme Committee of Free Officers. However, Nuri's attempts to preserve the loyalty of the military by generous benefits failed.

The Iraqi monarchy and its Hashemite ally in Jordan reacted to the union between Egypt and Syria (February 1958) by forming the Arab Federation of Iraq and Jordan. (Kuwait was asked to enter the union; however, the British opposed this.) Nuri was the first prime minister of the new federation, which was soon ended with the coup that toppled the Iraqi monarchy.

Fall of monarchy and death

As the 1958 Lebanon crisis escalated, Jordan requested the help of Iraqi troops, who feigned to be en route there on 14 July. Instead, they moved on to Baghdad, and on that day, Brigadier Abd al-Karim Qasim and Colonel Abdul Salam Arif seized control of the country and ordered the Royal Family to evacuate the Rihab Palace in Baghdad. They congregated in the courtyard—King Faisal II; Prince 'Abd al-Ilah and his wife Princess Hiyam; Princess Nafeesa, Abdul Ilah's mother; Princess Abadiya, the king's aunt; and several servants. The group was ordered to turn facing the wall and were shot down by Captain Abdus Sattar As Sab', a member of the coup. After almost four decades, the monarchy had been toppled.

Nuri went into hiding, but he was captured the next day as he sought to make his escape. He was shot dead and buried that same day, but an angry mob disinterred his corpse and dragged it through the streets of Baghdad, where it was hung up, burned and mutilated, ultimately being run over repeatedly by municipal buses, until his corpse was unrecognizable.[12]

Personal life and family

Nuri and his wife had one son, Sabah As-Said, who married an Egyptian heiress, Esmat Ali Pasha Fahmi in 1936. They had two sons: Falah (born 1937) and Issam (born 1938). Sabah As-Said is supposed to have taken an Iraqi-Jewish woman as a second wife and had a child with her when Jews accounted for 25-40% of Baghdad's population. After being ousted from Iraq, both his second wife and child fled to Israel.[13]

Falah, who worked as King Hussein's personal pilot, was first married to Nahla El-Askari and had one son, Sabah. He later married Dina Fawaz Maher in 1974, the daughter of a Jordanian army general, Fawaz Pasha Maher, and had two daughters: Sima and Zaina.

Falah died in a car accident in Jordan in 1983. Issam was an artist and architect based in London who died in 1988 from a heart attack.[14]

See also

- Kinahan Cornwallis – British Ambassador to Iraq

- Fritz Grobba – German Ambassador to Iraq

Notes

- ↑ Nakash, Yitzhak (2011). Reaching for Power: The Shi'a in the Modern Arab World. Princeton University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-1400841462.

- ↑ Rolls, S. C., Steel Chariots in the Desert London, Jonathan Cape, 1940, p. 21-2, 41–2

- ↑ Rolls, S. C. Steel Chariots in the Desert London pp163-8

- ↑ Lukutz, p. 95

- ↑ Batatu, p. 345.

- ↑ "'File 11/44 Leading Personalities in Iraq, Iran & Saudi Arabia' [32v] (64/96)". Qatar Digital Library. 10 September 2018.

- ↑ Batatu, pp. 350–351.

- ↑ Esther Meir-Glitzenstein (2 August 2004). Zionism in an Arab Country: Jews in Iraq in the 1940s. Routledge. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-135-76862-1.

in mid September 1950, Nuri al-Said replaced...as prime minister. Nuri was determined to drive the Jews out of his country as quickly as...

- ↑ Orit Bashkin (12 September 2012). New Babylonians: A History of Jews in Modern Iraq. Stanford University Press. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-8047-8201-2.

- ↑ Ali, A.-M.S. (15 March 1990). 9 investment policies in Iraq, 1950–87. International Monetary Fund. doi:10.5089/9781557751409.071. ISBN 9781557751409. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - 1 2 Dawisha, pp. 182–183.

- ↑ "At first [he] was buried in a shallow grave but later the body was dug up and repeatedly ran over by municipal buses, until, in the words of a horror-struck eyewitness, it resembled bastourma, an Iraqi [pressed] sausage meat." Simons, Geoff; Iraq: From Sumer to Saddam, p. 218

- ↑ "Foreign News: The Grandson of Nuri". Time. 11 August 1958 – via content.time.com.

- ↑ Al-Ali, and Al-Najjar, D., We Are Iraqis: Aesthetics and Politics in a Time of War, Syracuse University Press, 2013, p. 42

Sources

- Batatu, Hanna: The Old Social Classes and New Revolutionary Movements of Iraq, al-Saqi Books, London, 2000, ISBN 0-86356-520-4

- Gallman, Waldemar J.: Iraq under General Nuri: My Recollection of Nuri Al-Said, 1954–1958, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1964, ISBN 0-8018-0210-5

- Lukutz, Liora: Iraq: The Search for National Identity, pp. 256-, Routledge Publishing, 1995, ISBN 0-7146-4128-6

- O'Sullivan, Christopher D. FDR and the End of Empire: The Origins of American Power in the Middle East. Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, ISBN 1137025247

- Simons, Geoff: Iraq: From Sumer to Saddam, Palgrave Macmillan, 2004 (3rd edition), ISBN 978-1-4039-1770-6

- Tripp, Charles: A History of Iraq, Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-521-52900-X

External links

- "Revolt in Baghdad". Time Magazine. 21 July 1958. Archived from the original on 20 January 2008. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- "In One Swift Hour". Time Magazine. 28 July 1958. Archived from the original on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- Newspaper clippings about Nuri al-Said in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW