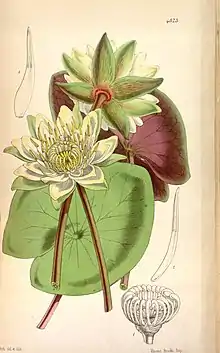

| Nymphaea amazonum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Order: | Nymphaeales |

| Family: | Nymphaeaceae |

| Genus: | Nymphaea |

| Species: | N. amazonum |

| Binomial name | |

| Nymphaea amazonum Mart. & Zucc.[1] | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Nymphaea amazonum is a species of water lily native to the region spanning from Mexico to tropical South America. It has been introduced to Bangladesh.[1]

Description

_(7060879859).jpg.webp)

Vegetative characteristics

Nymphaea amazonum is an aquatic herb.[2] It has dark brown to black, subcylindrical rhizomes, which can reach lengths of 10 centimetres (3.9 in) and widths of 3 centimetres (1.2 in).[3] The broadly ovate-elliptic leaf blade reaches 32 centimetres (13 in) in length and 26 centimetres (10 in) in width.[4] The actinodromous venation on the abaxial side of the mature leaf features strongly prominent and rounded veins.[2] The petiole is up to 8 mm wide and exhibits a ring of trichomes towards the apex.[4]

Generative characteristics

_(20935222715).jpg.webp)

The nocturnal flowers float on the water surface.[2] They are attached to 10 mm wide peduncles, which rarely exhibit a ring of trichomes towards the apex.[4] The strong floral fragrance has been said to resemble that of Magnolia fuscata,[5] a synonym of Magnolia figo var. figo.[6] It has also been characterised as very pleasant.[7][8][9] The fragrance is also said to resemble petrol, xylol,[3][4] benzene, PDB, turpentine, benzol, xylene, and acetone.[4] Fruits are produced very frequently.[4] Up to 22000 seeds are found in a single fruit.[5] The ovoid seeds are 1.3 mm long and 0.9 mm wide.[3] They are smooth, pilose and exhibit trichomes in continuous longitudinal lines.[2]

Cytology

The diploid chromosome count is 2n = 18.[4]

Reproduction

Vegetative reproduction

Nymphaea amazonum is stoloniferous,[4] but does not produce proliferating pseudanthia.[2]

Generative reproduction

The seed dispersal is hydrochorous (i.e. water-dispersed) or ornithochorous (i.e. bird-dispersed).[10]

Taxonomy

It was first described by Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius and Joseph Gerhard Zuccarini in 1832.[1]

Type specimen

The type specimen was collected in Brazil.[4]

Placement within Nymphaea

It is placed in Nymphaea subgenus Hydrocallis.[4]

Former subspecies

Nymphaea amazonum was sepataed into the two subspecies Nymphaea amazonum subsp. amazonum and Nymphaea amazonum subsp. pedersenii Wiersema.[4] This view was later rejected and Nymphaea amazonum subsp. pedersenii Wiersema was then treated as a separate species Nymphaea pedersenii (Wiersema) C.T.Lima & Giul. in 2021.[11]

Conservation

In Puerto Rico, USA Nymphaea amazonum faces habitat destruction.[12] It is considered to be endangered (EN) in Cuba, as it faces diminishing and deteriorating habitats caused by agricultural practices, the influence of exotic flora and fauna, livestock farming, sedimentation, and pollution.[13] In the Liste rouge de la flore vasculaire de Guadeloupe of 2019, Nymphaea amazonum is listed as data deficient (DD).[14]

Ecology

Habitat

In the Pantanal, it can be found in permanent ponds.[15] It is also found in lagoons and canals.[16] It is found growing in mixtures of clay and sand or in sandy-quartzitic soils.[13] Rhizomes of Nymphaea amazonum can endure periods of drought in moist sediments. In the floodplains of the Amazon, it faces competition from aquatic and semi-aquatic grass species.[17]

Pollination

The strong floral fragrance attracts beetles of the genus Cyclocephala.[19] The beetle species Cyclocephala castanea pollinates the flowers of Nymphaea amazonum.[18]

Uses

Nymphaea amazonum is used as a medicine and for food.[1] The rhizomes are edible.[15] It has the ability to absorb the pesticides cyhalothrin and imidacloprid from the water.[20][21] It exhibits antimicrobial properties in the treatment of ulcers.[22] The flowers have been used in the treatment of herpes and erysipelas.[23]

Cultivation

It is rare in cultivation.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Nymphaea amazonum Mart. & Zucc". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Nymphaea amazonum Mart. & Zucc". Flora e Funga do Brasil (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- 1 2 3 Stoffers, A.L.; Lindeman, J.C. (1979). Flora of Suriname. Brill. p. 373-375. ISBN 978-90-04-06062-3. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Wiersema, J. H. (1987). A monograph of Nymphaea subgenus Hydrocallis (Nymphaeaceae). Systematic Botany Monographs, 1-112.

- 1 2 3 Henkel, F., Rehnelt, F., Dittmann, L. (1907). "Das Buch der Nymphaeaceen oder Seerosengewächse." p. 76. Germany: Henkel.

- ↑ "Magnolia figo var. figo". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ↑ Otto, F.; Dietrich, A. (1856). Allgemeine Gartenzeitung (in German). Verlag der Nauck'sche Buchhandlung. p. 64. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- ↑ Lóczy, L.; Hungary. Földművelésügyi Minisztérium (1897). Resultate der wissenschaftlichen Erforschung des Balatonsees (in German). In Kommission von E. Hölzel. p. 7-PA33. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- ↑ Otto, E.; Mettler, R. (1855). Neue allgemeine deutsche Garten- und Blumenzeitung (in German). R. Kittler. p. 4-PA78. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- ↑ Lot, A. (1999). Catálogo de angiospermas acuáticas de México: hidrófitas estrictas emergentes, sumergidas y flotantes. Cuadernos del Instituto de Biología (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. p. 93. ISBN 978-968-36-7928-4. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- ↑ "Nymphaea pedersenii (Wiersema) C.T.Lima & Giul". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ↑ Woodbury, R.O. (1975). Rare and Endangered Plants of Puerto Rico: A Committee Report. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service. p. 61. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- 1 2 Cruz, A.J.U.; González-Oliva, L.; Carbó, R.N. (2010). Libro rojo de la flora vascular de la provincia Pinar del Río (in Spanish). Universidad de Alicante. p. 317. ISBN 978-84-9717-061-1. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- ↑ "Nymphaea amazonum Mart. & Zucc., 1832". Inventaire National du Patrimoine Naturel (in French). Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- 1 2 Damasceno-Junior, G.A.; Pott, A. (2022). Flora and Vegetation of the Pantanal Wetland. Plant and Vegetation. Springer International Publishing. p. 710. ISBN 978-3-030-83375-6. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- ↑ Liogier, A.H.; Martorell, L.F. (2000). Flora of Puerto Rico and Adjacent Islands: A Systematic Synopsis. Ed. de la Universidad. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-8477-0369-2. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- ↑ Junk, Wolfgang J.; Piedade, Maria Teresa F. (1997). "Plant Life in the Floodplain with Special Reference to Herbaceous Plants". The Central Amazon Floodplain. Vol. 126. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 147–185. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-03416-3_8. ISBN 978-3-642-08214-6.

- 1 2 Kaufman, L.; Mallory, K.; New England Aquarium Corporation (1993). The Last Extinction. MIT Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-262-61089-6. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- ↑ Heckman, C.W. (2013). The Pantanal of Poconé: Biota and Ecology in the Northern Section of the World's Largest Pristine Wetland. Monographiae Biologicae. Springer Netherlands. p. 178. ISBN 978-94-017-3423-3. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- ↑ Arora, N.K.; Kumar, N. (2019). Phyto and Rhizo Remediation. Microorganisms for Sustainability. Springer Nature Singapore. p. 98. ISBN 978-981-329-664-0. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- ↑ Malik, J.A. (2022). Advances in Bioremediation and Phytoremediation for Sustainable Soil Management: Principles, Monitoring and Remediation. Springer International Publishing. p. 68. ISBN 978-3-030-89984-4. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- ↑ Rai, M.; Feitosa, C.M. (2022). Eco-Friendly Biobased Products Used in Microbial Diseases. CRC Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-000-61466-4. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- ↑ Deutscher Apotheker-Verein (1879). Jahresbericht über die Fortschritte der Pharmacognosie, Pharmacie und Toxicologie (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 39. Retrieved 2023-12-11.