Offshore installation security is the protection of maritime installations from intentional harm.[2] As part of general maritime security, offshore installation security is defined as the installation's ability to combat unauthorized acts designed to cause intentional harm to the installation.[2][3][4][5] The security of offshore installations is vital as not only may a threat result in personal, economic, and financial losses, but it also concerns the strategic aspects of the petroleum market and geopolitics.[6][7]

Offshore installations refer to offshore platforms, oil platforms, and various types of offshore drilling rigs. It also is a general term for mobile and fixed maritime structures which includes facilities that are intended for exploration; drilling; the production, processing, or storage of hydrocarbons, and other related activities regarding the processing of fluids lying beneath the seabed.[8][2] Offshore installations are most commonly engaged in drilling actions located in the continental shelf of a country and form a major part of the petroleum industry's upstream sector.[9]

Whilst records of security incidents date to the 1960s, the matter did not appear in academic writings until the early 1980s .[10][11] A milestone is the 1988 SUA Act & Protocol which criminalized crime or violence against ships or fixed platforms.[2][12] After the September 11 attacks in 2001, there was increased awareness of possible threats in the offshore energy sector.[13][14] Threats [15][16][17] stem from sources such as pirates, environmental extremists, and other criminals, and they may vary in gravity and frequency.[2][10] There are a variety of protective mechanisms in place, and these range from international legal frameworks to specific industry planning and responses.[18][17]

History

1960s - 2000s

Record keeping of security incidents of offshore installations dates back to the 1960s,[10] but it was not until the early 1980s that possible threats were first addressed within academic literature.[11][10] This lack of protection left the assets vulnerable to attacks;[2][10][17] however, with the Achille Lauro attack in 1985, the awareness for the protection of maritime targets, including offshore installations, increased.[2] The attack is seen as a major driver for the 1988 adoption of the Convention For The Suppression Of Unlawful Acts Against The Safety Of Maritime Navigation (SUA Act) criminalizes behavior of crime or violence against ships including attacks of terrorism and piracy.[12][19] The signing of the accompanying SUA Protocol, the Protocol for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts against the Safety of Fixed Platforms Located on the Continental Shelf , which prohibits and punishes behavior that may threaten the security of offshore fixed platforms is seen to present a milestone in offshore installation security.[2] In the same year Brian Michael Jenkins published a paper under the RAND Corporation and was the first to comprehensively list a record of historical attacks on offshore installations and identify the main methods of attack.[10] By the late 1980s the awareness of installation security had increased, and the first international legal regulation was in place. Nevertheless, industry standards with regards to the protection of offshore installations were still low.[17]

September 11 attacks as turning point

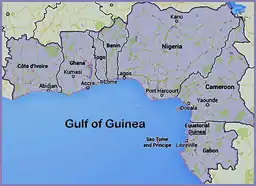

The 9/11 attacks marked a turning point in the international awareness and policy towards the comprehensive protection of offshore energy sector as political engagement with the topic increased.[4][2] Moreover, since 2004, the international community experienced an increase in the attacks on offshore installation due to reasons such as the increased capabilities of adversaries, political instability within certain nations, and armed conflicts in oil producing countries. For example, since 2006 the conflict in the Niger Delta has resulted in increased attacks in the Gulf of Guinea and raised security level.[13]

According to the International Energy Agency, the security of offshore oil and gas industry is currently of economic and strategic importance as about one quarter of the global energy supply stems from offshore sources.[4][2][9][6] [20] The resulting overall development towards heightened awareness and recognition of the issue has affected the organization of the offshore oil and gas sector within their installations. For example, some companies include a security division within their Health, Safety & Environment departments.[21] This overall development has brought changes to the international regulatory framework; namely, the passing of the ISPS Codes and the 2005 amendments to the 1988 SUA Convention and Protocol. Additionally, national laws have been enacted to include critical infrastructure protection policies (for further information see below 'Protection Mechanisms').[14][17]

Security threats

While a security threat is seen as "any unlawful interference with offshore oil and gas operations or an act of violence directed towards offshore installations",[22] there are several ways of how to classify the various threats facing offshore installations. The most comprehensive and encyclopedic compilation is Dr. Mikhail Kashubsky in his 2016 book. Offshore Oil and Gas Installations Security: An International Perspective.[2] The book includes a comprehensive dataset of past attacks and security incidents involving offshore oil and gas installations entitled the Offshore Installations Attack Dataset (OIAD).[23] In his writing, Kashubsky established an offshore security threat nexus in which he classifies the different threats. This classification identifies the people and organizations behind the threats as an analysis to learn more about their motivation, intent and tactics, to develop an effective response.[24]

Specifically, there are three factors taken into account by Kashubsky when assessing the offshore security threats: geography and other enabling factors, motivations and objectives, and capabilities and tactics. With regards to geography, the location of the offshore installation is identified for possible vulnerability. Other enabling factors refer to how events such as civil wars or political unrest in the region might effect offshore security. Motivations and objectives highlight the difference in intentions by the respective threats and how this relates to a differing methods in which they might deploy threats methods. Capabilities and tactics, address how to adapt defensive operations depending on the type of type and aim of a threat. These can range from piratical kidnapping tactics to external sabotage. Since threats are seen as being motivated by a range of objectives, the threats are also seen as being interlinked and overlapping. Lastly, Kashubsky ranks the different threats according to the API Security Risk Assessment methodology.[25] This consists of a 5-level threat ranking system that define threat rankings for the petroleum and petrochemical industry, where 1 is very low, 2 is low, 3 is medium, 4 is high, and 5 is very high. This ranking is based on these three factors as well as the frequency of past incidents.[2]

The offshore security threat nexus identifies and ranks the following threats:

_approaches_a_suspected_p.jpg.webp)

- Civil protest: These are interferences caused by non-violent environmental activists, indigenous activists, labour activists, striking workers, anti-government protesters or the like, usually employing non-violent and non-destructive measures. API-SRA Ranking: High

- Cyber threats: These present a broad spectrum of motivations and capabilities; however, there is a trend of cyber-attacks to target critical infrastructure targets, attacks that can be executed from any location worldwide. API-SRA Ranking: High

- Inter-state hostilities: These are certain actions of nation-states that take the form of interstate armed conflict and wars, maritime boundary disputes, or state terrorism. API-SRA Ranking: High

- Piracy: Piracy activities are those acts that seek financial gain and it describes the act of piracy. API-SRA Ranking: Medium

- Insurgency: These include regular or guerrilla combat against the armed forces of an established authority and the government or administration which act in opposition to civil authority. These may also relate to piracy as a financial tactic. API-SRA Ranking: Medium

- Organised crime: This addresses criminal activities with illegal ventures for financial purpose, specifically those which are non-ideological. API-SRA Ranking: Medium

- Internal sabotage: This addresses the deliberate destruction, disruption, or damage of equipment by dissatisfied employees, current or former. It also includes the intentional disclosure of sensitive and confidential information to third parties. API-SRA Ranking: Medium

- Terrorism: This concerns activities organised for terrorist purposes with a political aim or a tactic to realise certain sub-goals. In this classification, violence is deliberately used. API-SRA Ranking: Low

- Vandalism: The concerns acts that damage cargo, support equipment, infrastructure, systems, or facilities. They can include violent actions of radical environmental and animal rights groups that intend to cause damage to company property. API-SRA Ranking: Very Low

With this classification system, the highest threats are seen to stem from civil protest, interstate hostilities, and cyber threats. On the other hand, terrorism threat is low, and vandalism even lower. The other categories provide a medium threat level.

Geographical considerations

The security of an offshore installation stands in close relation to its geographical location.[2] Even though attacks have taken place in all regions of the world, most occurred in political and economically unstable countries. The majority of these, more than 60%, took place off the coast of Nigeria.[13] This raised the notion that there are national and regional dimensions that must be considered.[26]

Regions of heightened concern include the following:[4]

- Gulf of Guinea with more than 60% of the attacks taking place there

- Bay of Benegal and the Asia Pacific region due to civil unrest onshore

- Persian Gulf which is in an oil rich region

- Indian Ocean specifically around the Horn of Africa

Possible consequences of security incidents

There is a variety of consideration when analyzing the consequences of a possible threat materializing. Within this, offshore installations security threats are considered hybrid-threats as the consequences may be felt by various organizations and sectors around the globe.[4]

Personal security concerns

Possible injury or death of offshore workers need to be considered. Attacks may result in grave injuries or other medical consequences, or loss of life in the worst case.[10][4]

Operational security concerns

A materialized security threat may result in the disruption of the functioning of the offshore installation due to the damage or harm on the operational site.[14]

Environmental security concerns

The consequences of oil spills, especially in the high seas, may be grave.[27] A possible oil spill may cause long-lasting damage to the immediate environment, but may have wider implications too. For example, the food security of a region may be compromised due to water contamination.[4] Not only may water offshore and in coastal waters be affected, but it also may cause toxic effects on shorelines and shallow inshore waters.[15] This could have a negative effect on the population living in the region.

Economic Security Concerns

A successful attack may result in economic concerns for a variety of people who are involved. First, for the operating company may suffer damage and also a loss of income when production is stalled. Additionally, a disruption of oil and gas supply to the market may result in volatile oil prices, which would carry an effect on global economy and the stock exchange.[28][6][7] An oil spill may also have significant effects on other sectors such as local fisheries and tourism which could experience losses.

Energy security concerns

With the offshore oil and gas sector being one fourth of the global energy production, offshore oil and gas extraction has become increasingly important in the evolving world energy scene.[7][17] Petroleum, as one of the most important energy resources of the earth, will remain an essential part of the global energy demand also in the future, as demands are not projected to curtail.[7] Thus, an uninterrupted petroleum supply is essential in light of the global energy security as a sustained disruption in oil supply may cause national emergencies.[14][2][29]

Strategic security concerns

A sustained disruption in oil and gas supply may also cause geopolitical concerns. It could present a weakened position of a nation within global politics as it loses power within those factors that govern international relations.[17]

Protection mechanisms

_engage_in_a_mock_assault_operation_in_the_Red_Sea.jpg.webp)

Offshore installations enjoy a number of protection mechanisms that are international, regional, and industry specific.

Legal mechanisms

UNCLOS Art. 60

The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provides a basic legal basis for protecting offshore installations.[30] Typically, offshore installations are deployed either in the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, or the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of a coastal state. Whilst the coastal state has full enforcement jurisdiction over all security matters in the territorial sea, in the contiguous zone it has also has powers over law enforcement issues which affect its domestic stability. This allows the coastal state to secure its offshore assets broadly through jurisdiction in these two zones. In the EEZ the rights are more limited, as the coastal state cannot restrict others' right to innocently transit the waters. 'Art. 60 of UNCLOS' gives coastal states the right to create a 500-meter safety zone around offshore installations which designates it as an area of restricted navigation where any passing vessel or boat may be considered a potential security concern. Within this zone, personnel may take appropriate measures to stop those who pose the threat.[14][18]

SUA Convention + protocol

The Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Maritime Navigation (SUA Convention) and its accompanying Protocol for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Fixed Platforms Located on the Continental Shelf (SUA Protocol) criminalized behavior of crime, violence, or behavior that may threaten the security of ships and fixed platforms.[19] The main purpose of the Convention was to ensure that appropriate action is taken against those who have committed unlawful acts against vessels and offshore oil and gas infrastructure as it obliges contracting Governments either to extradite or prosecute alleged offenders.[2] The 2005 amendments, moreover, addressed vulnerable elements of the maritime-based oil and gas industry and drew attention to potential acts of terrorism. These actions establish that consideration should be also given also to the oil and gas industry.[14][17] With this the SUA Convention and Protocol provided the first international treaty and framework for combating and prosecuting criminals and terrorists who have attacked or used a tanker or a fixed oil or gas installation as part of a terrorist operation.[17][14]

ISPS Code

The International Ship and Port Facility Security Code (ISPS) prescribed responsibilities to governments, companies and personnel to detect security threats and take preventive measures against security incidents affecting ships or port facilities used in international trade. It additionally introduced maritime security levels for quick crisis communication which provides industry members with a framework for crisis response. The ISPS Code is enacted in national law in the EU and the US.[31][17]

Industry mechanisms

International Association of Oil and Gas Producers (OGP documents)

The International Association of Oil and Gas Producers is asserted as the "voice of the global upstream oil and gas industry"[32] and has published several documents in the form of reports that recommend best practices to be introduced in the oil and gas industry including enhanced security of energy installations.[16] The pertinent documents are:

ISO Standards ISO 31000:2009

The voluntary international ISO Standards introduced recommendations and best practices for industry actors. The ISO 31000:2009 Risk Management: Principles and Guidelines is a standard presenting internationally accepted best practice frameworks and guidelines for action on risk management.[3][14] It presents a systematized protocol to identify, analyse, evaluate, and treat possible risks to support strategies for major safety and security incident prevention, response, and recovery. Implementation of these standards is designed to both prepare for and react to an security emergency.

Risk assessment mechanisms

RAMCAP

RAMCAP or Risk Analysis and Management for Critical Asset Protection is a framework for analyzing and managing the risks associated with attacks against the United States national critical infrastructure assets. It provides an overarching 7-step methodology for assessment and management of risks and their impact. It has been developed by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers to be used by the staff and management of infrastructure facilities and is also used by the American industry to report to the US Department of Homeland Security[36][37][38][39]

CRISRRAM

CRISRRAM, or critical infrastructures and systems risk and resilience assessment methodology, is a security methodology developed by the European Commission. It addresses risks and vulnerabilities of critical infrastructure at asset, system, and societal levels which takes into account environmental and man-made security hazards. It provides industry professionals with a framework to analyse, act, and a security emergency.[38]

SVA Methodology for the Petroleum and Petrochemical Industries

The Security Vulnerability Assessment (SVA) Methodology for the Petroleum and Petrochemical Industries from the American Petroleum Institute and the National Petrochemical & Refiners Association aims at maintaining and increasing the security of energy facilities in the petroleum sector. The document establishes a security vulnerability assessment methodology to identify and analyse the threats and vulnerabilities those energy installations face.[38][25]

Moreover, general security risk management practices, such as enterprise risk management are employed throughout the sector.

See also

References

- ↑ Office of Ocean Exploration and Research (15 December 2008). "Types of Offshore Oil and Gas Structures". NOAA Ocean Explorer: Expedition to the Deep Slope. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Kashubsky, M. (2016). Offshore Oil and Gas Installations Security: An International Perspective. Abingdon, UK: Informa Law.

- 1 2 ISO (September 2007), ISO 28000:2007, pg. 2, Retrieved May 25, 2019

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cordner, L. (2018). Maritime Security Risks, Vulnerabilities and Cooperation: Uncertainty in the Indian Ocean. New South Wales, AUS: palgrave macmillan

- ↑ Bueger, Christian (2015). "What is maritime security?". Marine Policy. 53: 159–164. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2014.12.005.

- 1 2 3 IEA. "World Energy Outlook". IEA. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 BP (June 2018). BP Statistical Review of World Energy. 67th Edition. Retrieved 24 May 2019

- ↑ Det Norske Veritas (2011). Offshore Standard DNV-OS-C101 - Design of Offshore Steel Structures, General (LRFD Method) (DNV-OS-C101). Høvik, Norway: Author. Retrieved 22 April

- 1 2 IEA (May 2018). Offshore Energy Outlook. Retrieved 23 May 2019

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jenkins, B.M. (1988). Potential threats to offshore platforms (P-7406). Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation

- 1 2 Jenkins, B.M & Cordes, B. & Gardela, K., & Petty, G. (September 1983). A Chronology of Attacks and other Criminal Actions Against Maritime Targets (P-6906). Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation. Retrieved 24 May 2019

- 1 2 United Nations, (March 1988). Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Maritime Navigation.

- 1 2 3 Kashubsky, M. (2013). Protecting offshore oil and gas installations: Security threats and countervailing measures. Journal of Energy Security, 11. Retrieved 18 April 2019

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sebastian, M.A. (2015). Critical Infrastructures – Offshore Installation Protection. Malaysia: Centre for Maritime Security & Diplomacy. Retrieved 17 April 2019

- 1 2 ITOPF (2018). Environmental Effects of Oil Spills. Retrieved 22 May 2019

- 1 2 IOGP (2018). Security. Retrieved 22 May 2019

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Herbert-Burns, R. (2009). Tankers, Specialized Production Vessels, and Offshore Terminals: Vulnerability and Security in the International Maritime Oil Sector. In R. Herbert-Burns, S. Bateman, & P. Lehr (Eds.). Lloyd's MIU Handbook of Maritime Security (pp. 133-159). Boca Raton, FL: Auerbach Publications

- 1 2 Kashubsky, M. & Morrison, A. (2013). Security Of Offshore Oil And Gas Facilities: Exclusion Zones And Ships' Routeing. Australian Journal of Maritime and Ocean Affairs. Vol. 5(1). Retrieved 17 April 2019

- 1 2 IMO. Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Maritime Navigation, Protocol for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Fixed Platforms Located on the Continental Shelf. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ↑ Batemans, S. & Bergin, A. (March 2009). Sea Change: Advancing Australia's Ocean Interests. Barton, AUS: Australian Strategic Policy Institute. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ↑ Mærsk Drilling. Health, Safety, Security & Environment. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ↑ Kashubsky, M. (2013). Protecting offshore oil and gas installations: Security threats and countervailing measures. Journal of Energy Security, 11. page 2. Retrieved 11 April 2019

- ↑ CCES (July 2016). Oil and Gas Installation Security. Barton, AUS: Centre for Customs and Excise Studies. Retrieved 22 May 2019

- ↑ Hansen, T.H. (2009). Distinctions in the Finer Shades of Grey: The "Four Circles Model" for Maritime Security Threat Assessment. In R. Herbert-Burns, S. Bateman, & P. Lehr (Eds.). Lloyd's MIU Handbook of Maritime Security (pp. 73-87). Boca Raton, FL: Auerbach Publications

- 1 2 API & NPRA (May 2003). Security Vulnerability Assessment Methodology for the Petroleum and Petrochemical Industries. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ↑ Vasilev, V.S. (2016). Some Specifics of Reducing the IED Risk in Offshore Security Environment. "Mircea cel Batran" Naval Academy Scientific Bulletin, Volume XIX (2).

- ↑ ITOPF (2018). Environmental Effects of Oil Spills. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ Yergin, D. (2011). The prize: The epic quest for oil, money & power. Simon and Schuster.

- ↑ Cordner, Lee (2009). Offshore Oil and Gas Industry Security Risk Assessment: An Australian Case Study. In R. Herbert-Burns, S. Bateman, & P. Lehr (Eds.). Lloyd's MIU Handbook of Maritime Security (pp. 169-187). Boca Raton, FL: Auerbach Publications

- ↑ United Nations (1982). United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

- ↑ IMO (2002). International Ship and Port Facility Security Code.

- ↑ "IOGP". Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ↑ IOGP (2014). Report No. 494. on Integrating Security in major projects.

- ↑ IOGP (2014). Security management system – Processes and concepts in security management

- ↑ IOGP (2016). IOGP Report No. 555 on Conducting Security Risk Assessments (SRA) in dynamic threat environments.

- ↑ Nikitakos, N. & Progoulakis, I. (August 2018). Security Assessment for Offshore Oil and Gas Assets. Malmö, SWE: World Maritime University. Retrieved 21 April 2019

- ↑ ASME (2005). RAMCAP Executive Summary. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- 1 2 3 OECD (April 2019). Good Governance for Critical Infrastructure Resilience. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ↑ Brashear, J.P. & William Jones, J. (February 2010). Risk Analysis and Management for Critical Asset Protection (RAMCAP Plus). Wiley Handbook of Science and Technology for Homeland Security. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

External links

- Kashubsky (2016). Offshore Oil and Gas Installations Security: An International Perspective

- Cordner, L. (2018). Maritime Security Risks, Vulnerabilities and Cooperation: Uncertainty in the Indian Ocean.

- IEA (2018). Offshore Energy Outlook.

- BP (2018). BP Statistical Review of World Energy. 67th Edition.