| First Reformed Protestant Dutch Church of Kingston | |

|---|---|

Church spire and south elevation, 2008 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Reformed Church in America |

| Leadership | The Rev. Kenneth L. Walsh[1] |

| Year consecrated | 1852 |

| Location | |

| Location | Kingston, NY, USA |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°55′58″N 74°01′08″W / 41.93278°N 74.01889°W |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Minard Lafever |

| Style | Renaissance Revival |

| General contractor | Hallenbeck & Brink |

| Groundbreaking | 1851[2] |

| Completed | 1852 |

| Construction cost | $33,000[2] |

| Specifications | |

| Direction of façade | south |

| Length | 117 feet (36 m)[2] |

| Width | 66 feet (20 m)[2] |

| Height (max) | 50 feet (15 m)[2] |

| Spire(s) | 1 |

| Spire height | 225 feet (69 m)[2] |

| Materials | Bluestone, wood |

| U.S. National Historic Landmark | |

| NRHP Reference no. | 08001089 |

| Designated as NHL | October 6, 2008[3] |

| Website | |

| Old Dutch Church | |

The Old Dutch Church, officially known as the First Reformed Protestant Dutch Church of Kingston, is located on Wall Street in Kingston, New York, United States. Formally organized in 1659, it is one of the oldest continuously existing congregations in the country. Its current building, the fifth, is an 1852 structure by Minard Lafever that was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2008,[4][5] the only one in the city. The church's 225-foot (69 m) steeple, a replacement for a taller but similar original that collapsed, makes it the tallest building in Kingston and a symbol of the city.

Lafever's building was described by Calvert Vaux as "ideally perfect". It is unique among his work as his only Renaissance Revival church that largely retains the original design, and the only stone church he is known to have built. Its interior includes stained glass by Louis Comfort Tiffany's company, and an extensive M.P. Moller pipe organ After a few early renovations, and the collapse of the higher original steeple, it has remained largely intact since 1892, although there have been continuing issues with one of the walls. One of the congregation's previous churches is across neighboring Wall Street. The church grounds also include a small cemetery with most of the burials predating its construction. Among them is George Clinton, a former governor and U.S. vice president.

The church has been active in Kingston's civic life. During the Revolutionary War George Washington paid a visit due to the church's strong support for the Patriot cause, and wrote a thank-you note exhibited in the church today. An annual dinner is held to commemorate the visit. George H. Sharpe raised a Civil War regiment at the church, and later erected a monument in the churchyard to those volunteers. Franklin Delano Roosevelt and members of the Dutch royal family, among other notables, have visited the church. It has also been the site of memorials to tragedy from the assassination of William McKinley in 1901 to the September 11 attacks in 2001.

Building

The church is located on a 1.4-acre (5,700 m2) lot at the east of uptown Kingston. It is a contributing property to the Stockade District. Main, Fair and Wall streets surround it on three sides; the north has some two-story commercial buildings. The old Ulster County courthouse is just to the northwest, across Wall. Amid a cluster of buildings on the south, across Main Street, is the building the current church replaced, now St. Joseph's Catholic church. Most of the neighboring buildings support the church's historic character, dating to the 19th or early 20th centuries.[2]

Tall shade trees surround the building and shelter its cemetery. An iron fence with stone posts encircles most of the property. Flagstone walks lead to the primary entrance on the south side and around the building, where another one leads from the tower entrance to Wall Street.[2]

Exterior

The building itself is faced in load-bearing locally quarried bluestone, set in a random ashlar pattern with limestone trim. It consists of a main sanctuary building oriented north–south with an east–west lecture hall wing on the north end and attached multi-stage bell tower at the northwest corner. The gabled roof is clad in raised-seam metal, with a modillioned wooden cornice. It is pierced by skylights corresponding to the exterior windows, currently covered in plastic, just above the roofline.[2]

Fenestration on both side profiles consists of five large round-arched stained glass windows framed by molded limestone casings with bracketed sills. On the east in the center is an engaged buttress added to shore up the wall. A three-bay projecting pavilion on the west supports the bell tower. Its entrance is a single door with round-arched window above and on the sides. Its lowest stage is a three-story masonry tower with wooden cornices separating the stories, topped by three frame ones above a curved cornice. The lower two are octagonal, one featuring a clock and the next louvered round-arched vents. The uppermost stage, the conical steeple, has ribs defining its eight facts and is covered with diamond-shaped wooden shingles.[2] Kingston's city ordinances prohibit the construction of any building taller than its base in the Stockade District.[6]

The lecture hall addition on the north is similar to the main church block. It is a two-story bluestone structure with slate roof, mostly shielded from view by the church and adjacent buildings.[2]

A similar projecting gabled pavilion, with battered corners, on the Main Street side frames the main entrance. Two bluestone steps with iron railings lead up to a pair of slightly recessed paneled wooden doors topped by a fanlight with tracery. The limestone surround is topped with a keystone. Limestone is also used for the corner bases and courses at ground level and continuing the cornice line at that level. Similarly appointed but smaller doors flank the main entrance.[2]

Interior

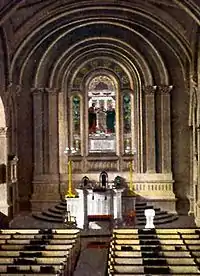

In the narthex a small display case contains items of significance from the church's history: the first communicants' tablet, and a letter from George Washington thanking the congregation for its hospitality to him on a 1782 visit (This is reportedly his only writing during the entire eight years of the Revolutionary War that mentions any religious institution.[7]) Across from the main entrance three round-arched doors corresponding to those on the outside lead into the main sanctuary.[2]

The sanctuary itself is painted off-white, with the stained glass windows, red carpeting, gilding and mahogany trim of the pews providing a contrast. Corinthian columns, creating lateral arcades, provide corbeled support to groin vaults. The arcading partially encloses the balcony. A simulated clerestory level is illuminated by the skylights supplemented by electric lighting in the original wall sconces. The walls themselves are plaster on lath with beaded wainscoting ending in a chair rail.[2]

A raised wooden platform supports the pulpit, carved with some classical motifs such as rectangular, rounded lozenges and foliation, some of it gilded, echoing the wall behind it. It has two front piers that resemble antae. On the wall above the pulpit is a Palladian Tiffany stained glass window depicting the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple framed by gilded moldings and flanked by pairs of fluted Corinthian pilasters. Bronze statues of angels are on either side.[2]

On the south wall is a choir loft with the church's pipe organ. It is in a case with another Palladian motif and carvings similar to those in the pulpit, and also framed with fluted Corinthian pilasters. A large swan-necked broken pediment is atop the case.[2]

The church's box pews have hinged doors, scrolled armrests and seat cushions. They all face forward on the ground floor except for the two rows in the front. On the upstairs galleries they face the opposite wall. Metal and marble memorial plaques line the walls, and a door on the northwest side leads to the tower vestibule.[2]

Cemetery

The remainder of the church lot is given over to its cemetery.[8] It contains around 300 headstones, many of which predate the current church. The stonework on many is detailed and high in quality.[2] 1710 is the earliest date for which one is legible, but church records show burials as early as 1679, and some that have not yet been translated may have taken place earlier. Not all graves were marked. The most recent stone dates to 1832.[9]

At least 70 of the stones are believed to be Revolutionary War-era veterans. George Clinton, former Governor of New York and U.S. Vice President under Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, is buried here under a large obelisk in the churchyard's southwest corner. He was moved here from Washington in 1908 and reburied in a full ceremony. Another large monument to "Patriotism" in the southeast corner honors the volunteers of the 120th New York Infantry during the Civil War. It was commissioned by George H. Sharpe, a Kingston native and colonel of volunteers for the 120th.[2]

Aesthetics

The Old Dutch Church was one of Lafever's last commissions, and considered his most fully developed application of the Renaissance Revival style. Architectural historian W. Barksdale Maynard says it "reveals an experienced architect at the height of his powers, broadening his approach beyond the Greek Revival he had done so much to popularize." The style may have also appealed to the church's congregation as a way of distinguishing itself architecturally within the city from the Second Reformed Dutch Church of Kingston, an offshoot church which had built a new Gothic Revival church nearby in 1850. It also may have been preferred as it made the church building look older than it actually was.[2]

Lafever abandoned the classical symmetry he had used for earlier churches such as the Old Whaler's Church in Sag Harbor for the church's exterior, preferring the more Picturesque choice of putting the tower on the side. The projecting front pavilion on the Main Street side creates the appearance of superimposed gables, much like those on the Church of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice. Eclecticism was another aspect of the Picturesque that showed up in Lafever's design. The battered piers at the corners give the main block and front pavilion a slight Egyptian Revival feel, as well as adding mass.[2]

The interior of the church follows English Renaissance forms popularized by Christopher Wren and James Gibbs, particularly some aspects of the latter's St Martin-in-the-Fields,[10] which again may have been chosen by the congregation to distinguish themselves from the Second Reformed Church. By using such a consciously English model, the church's congregation signaled the full assimilation of Dutch Americans, many of whom had continued to speak Dutch for some years after independence, into the predominantly English-influenced culture of the mid-19th century United States. He used a 3:5:7 ratio for the proportions, representing the Trinity, the human senses and the days of Creation respectively.[7] Calvert Vaux, when declining a commission for a new pulpit at the church three decades later, called its forms and symmetry, "ideally perfect".[2]

History

The First Protestant Dutch Reformed Church of Kingston has held worship services for 350 years, making it one of the oldest continuously existing congregations in the U.S. The current building is its fifth.

For the first 170 years of its existence it was the only church in Kingston, and the only Dutch Reformed Church for much of the west side of the Hudson River. Fifty other churches in the region were started under its auspices. Its birth, marriage and death records are complete to 1660, making it one of the oldest such collections in the country and an important resource for genealogists.[9]

17th and 18th centuries

Like many churches, the Old Dutch Church began with informal meetings, in its case starting around May 1658, when Kingston was still known as Wiltwyck, part of the Dutch colony of New Netherland. Jacob Stoll, a local settler, led services for 11 others in his house in the absence of an ordained minister or actual building. The following year it was formally organized, and in 1660 received its first dominie, or minister, Hermanus Blom.[2] A parsonage was built at the order of Peter Stuyvesant in 1662. It was used as a school and court as well, and possibly an Indian trading post.[9]

Church lore holds that a crude log meetinghouse, built into the stockade that had been built around the small city,[7] was erected near the current location in 1661, although whether it was there has been disputed. Any structure that did exist was destroyed in 1663 during the Second Esopus War.[7] By 1680 a small stone building was in use there. Records of the time describe it as 60 feet (18 m) wide long and 45 feet (14 m) wide. A later history notes that it was extravagantly furnished for the time and place with stained glass windows bearing coats of arms.[2]

Services of that era were austere and lengthy, conducted in strict accordance with Calvinist beliefs. On the Sabbath day, liquor consumption, discharge of firearms and beating of drums were forbidden, with steadily escalating penalties starting at one Flemish pound. The church itself was unheated, due to fears of fire. Some congregants brought small stoves to warm their feet in winter. They sat in seats on either side of the sanctuary. A Vorleser (reader) and Vorsanger (music leader) assisted the minister. There were no books for the audience since many were illiterate. The church did not have an organ since they were considered a work of the devil.[9]

After the Second Anglo-Dutch War, the 1667 Treaty of Breda turned New Netherland over to the English, and Wiltwyck became Kingston. The trustees of the Kingston Patent generously funded the church, by transferring to it a thousand acres (400 ha) in the north of the town, which the church subdivided and sold.[9]

In 1712 the church requested a royal charter; seven years later it was granted by King George I in exchange for a peppercorn in rent every year.[9] Two years later, in 1721, it was expanded, early in the half-century tenure of Dominie Petrus Vas. A doop huys, a sort of chapel, was built to handle baptisms, meetings and other consistorial activities. Vas would, three decades later, oversee the construction of a second church building. Surviving prints show a gambrel-roofed meetinghouse two bays wide with a tower on the front. Its siding seems to have been limestone rubble, although the first print shows a material that could be either in a coursed ashlar pattern or parging to mimic coursed stone. Fenestration consisted of three round-arched windows along the sides. It was dedicated on November 29, 1752, by Georg Wilhelm Mancius, Vas's assistant.[2]

In October 1777, the church, like many other buildings in the city, was damaged by fires set by British forces retaliating against the recently proclaimed capital of the independent state of New York after the Battle of Saratoga. It was gutted, but the walls still stood. The congregation strongly supported the Patriot cause throughout the war.[7] In 1782, George Washington, garrisoned near Newburgh to the south, visited the church. He enjoyed his visit enough that he wrote the congregation the letter of thanks currently displayed in its museum.[2] By 1790 repairs to the church were complete. The tower was rebuilt with a cupola and clocks on all sides.[9]

19th century

The first decade of the new century brought change to the church and its community. In 1803 the trustees of the patent decided to sell all their remaining landholdings and dissolve. Upon completing this task two years later, they disbursed £3,000 to the church. That same year Kingston was formally incorporated as a village. In 1808 the village surveyed the property on which the church proper stood and formally conveyed it to the church. The next year, the church began to break with its cultural roots, holding its last services in Dutch.[2]

In 1816 the church established the first Sunday school in Ulster County. Its goal was to teach local African-Americans to read the Bible. The church did in this in the context of publicly saying that it looked forward to "the time when people of color will be entitled to the rights of citizenship".[11]

Burials in the church cemetery stopped in 1830. A cholera epidemic swept Kingston that year, and as the graveyard filled up quickly the consistory decided against allowing any more. One exception was a woman who died in 1832, possibly the last burial in the churchyard.[9]

The church building, too, was reaching the limit of its capacity. The original parsonage was torn down and a new brick church with Romanesque arched windows erected. Its roof was damaged by a lightning strike in 1840 that tore a large hole in it. No one was present in the church at the time and services were held the next Sunday.[9]

Within two decades the new church was already reaching its capacity, with over a thousand congregants. In 1848, a group of parishioners broke away when the Classis of Ulster denied permission for a new building and formed the Second Reformed Dutch Church of Kingston two blocks away on Fair Street, ending the Old Church's hegemony over Kingston. This did not adequately relieve the overcrowding. In 1850 the church resolved to replace the old building, which was still suffering the effects of the lightning strike.[2] The next year the church bought another nearby parcel to enlarge its cemetery, in preparation for the construction of a new building. How they chose Lafever is not known, but in 1852 they began construction of his church, grounding the building in trenches instead of excavating a full cellar, so as not to disturb the graves in the area. The cornerstone was laid in May.[9]

After a year and a half of construction work, costing $33,000 ($1,161,000 in contemporary dollars[12]), the church was dedicated in September 1852. The contractors were paid for work beyond the original scope. It is not known whether Lafever ever visited the site or modified his design while construction was underway.[2]

Two years later, its original steeple, at 239 feet (73 m)[9] the tallest in the state at that time,[7] crashed to the ground when the roof collapsed during a Christmas Eve windstorm. The cause was traced to the 50 tons (46 tonnes) of slate roofing the church elders had substituted for Lafever's tin, creating a load greater than the structure was intended to support.[2]

The church sold the brick building, which it no longer needed. After a few other owners, it became the property of the state, which used it as an armory. When the Civil War started, the church, long active in the abolitionist movement,[7] became the center of parishioner George H. Sharpe's efforts to organize the 120th New York Infantry. The unit drilled in the armory and fought in battles ranging from Fredericksburg to Appomattox.[7] Its battle flags hang in the Old Church's narthex.[9] After the war, it was consecrated as St. James Catholic Church

In 1861 the church closed for ten months in order to erect the current steeple. Another structural problem, the shifting of its east wall, had been noticed and was mentioned in a report by the state engineer's office in 1874. It was attributed at the time to the lack of a full basement due to the decision to leave the underlying graves intact. In 1882 the church started another building campaign to address this and other issues.[2]

Not only had the wall shifted, the ceiling had suffered. It was replastered, and the exterior buttress was built. Lafever's original tin was restored to the roof.[2] A small stone chapel was built on the north side.[9]

At the beginning of 1892, the church dedicated the new stained glass window, a gift in remembrance of a congregant's parents. Made from Favrile glass by one of Louis Comfort Tiffany's artists, it depicts the Presentation of Christ at the Temple. It was lit at first by gas, and later electricity. It marks the last significant change to the church's interior.[2]

Four years later, in 1896, Sharpe's monument to his volunteers was added to the graveyard. The 16-foot (4.9 m) statue, the work of Byron M. Pickett, was dedicated in a ceremony attended by many of the 120th's former members.[9] It is the only Civil War monument erected to a unit's members by that unit's commander,[7] and one of the rare examples of such a war monument anywhere.[13] The plot it stands on was reportedly deeded to the monument itself.[9]

20th century

The early 20th century saw several events related to funerary matters. In 1901, the church held one of the official funeral services following the assassination of President William McKinley. Seven years later, the remains of George Clinton, an Episcopalian, were transferred from Washington to the churchyard, where he was reburied with full honors, under the same obelisk he had originally been buried under, within sight of the steps of the courthouse where he had been sworn in as New York's first governor in 1777.[13][14] Shortly after the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, the church held a memorial service for the victims.[7]

The following year a small stone building at the corner of Washington Avenue and Joys Lane, known as Bethany Chapel, was sold to the church. In 1932 Franklin D. Roosevelt, then governor and himself a Dutch American native of the Hudson Valley, spoke at ceremonies commemorating the 150th anniversary of Washington's visit.[9]

Bethany Chapel was sold in 1946, and burned down shortly thereafter. Five years later, when the church needed to expand its facilities again, the small chapel on the north that had been created in 1883 was enlarged to include a second story, with choir room, classroom and kitchen as well. Bluestone sympathetic to the original design was used. The new wing was named Bethany Annex in honor of the chapel building.[2] The next year, to celebrate the centenary of the church building, Queen Juliana of the Netherlands and her consort, Bernhard, attended services. Her daughter, then-Princess Beatrix, followed her in 1959, during commemorations of Henry Hudson's voyage up the river on the Halve Maen and the church's tercentenary.[14]

The later years of the 20th century would see more renovations. In the mid-1970s the east wall was shored up again, and the steeple was repainted in its current white from its previous gray.[14] In 1996 the Patriotism monument to the 120th was restored.[9] Other historic Kingston buildings benefited from the church's focus on restoration and preservation. When city hall began suffering from neglect in the late 20th century, some congregants removed the surviving bas-relief plaster lunettes depicting scenes in the city's history from the building's facade and stored them in the church's basement. They were returned to city hall when it was restored in 2000.[7]

21st century

As with the century just past, the first major event of the new century at the church was an observance of national grief. On the evening of September 11, 2001, it was opened to all members of the community for impromptu services in the wake of that day's terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center.[7]

After several years of restorations and maintenance, the church, with the help of the State Historic Preservation Office, applied to the National Park Service (NPS) for National Historic Landmark status.[15]

U.S. Representative Maurice Hinchey lobbied the NPS on the church's behalf, and in October 2008 his office made the first announcement of the designation.[16] Several months later he was also present as the church officially received its plaque.[17] That year, the church celebrated its 350th anniversary at events like its annual Washington dinner and Pinkster.[13] The current pastor, Ken Walsh, started the year by doing the liturgy as it was in 1659, in the vestments a minister of that era would have worn. He has advanced to a different century every three months, to reach the present day by the end of the year.[18]

Hinchey spoke at the church in 2010 to lobby for passage of a federal urban development bill which included a $350,000 grant to shore up the church, replacing steel girders which had done that since 2004. At that time the bill had passed the House but not the Senate. The structural problems have been attributed to the graves it was built on.[19]

The church today

The church and its congregation are "committed to providing worship, education, evangelism, social action, and fellowship", according to their mission statement.[20] It professes its faith thus:

We acknowledge the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments to be our rule in faith and practice; we celebrate the Sacraments of Holy Baptism and Communion as living sign and seal of Christ's presence among us. We confess our faith using the Apostle's Creed, the Nicene Creed and the Heidelberg Catechism.[21]

It holds regular Sunday services,[22] Sunday School, confirmation classes, Sunday adult discussion programs and a "Souper Thursday" program that complements homemade soup with spiritual discussion.[23] There is a women's ministry[24] and men's club.[25] The church also publishes a monthly newsletter, Steeple Chimes.[26]

There are several groups affiliated with the church. The Friends of Old Dutch is a non-profit that raises money for the continued maintenance and preservation of the church building.[27] Two musical groups, the Kingston Community Singers[28] and Mendelssohn Club of Kingston,[29] rehearse and perform at the church.

Organ

By the 19th century, the church's original aversion to organs had abated, and a photo of the interior of the 1832 church from that era shows an organ. When the current church was built, Henry Erben, who had built the pipe organs at the First Reformed Church in Albany and St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York, was hired to build the new Dutch Church's organ.[30]

Erben's facade and case remain today, but the pipes and internal mechanics were replaced with an E.M. Skinner organ in 1903. It was powered by a water-driven motor, providing a continuous flow of air. The church's consistory had written to the city requesting that water pressure be maintained on Sundays to allow the organ to function. In 1914 an electric motor was installed to replace the water. A smaller Echo organ was given to the church in 1927.[30]

In the mid-1950s the church decided to recondition the organ. After reviewing several bids, its Music Committee decided to award the contract to the M. P. Moller company, with a plan for further extensions of the organ. The reconditioned organ was dedicated in 1956 with a recital including Johann Sebastian Bach's Toccata and Fugue in D minor. Its console is still in use, after many emergency repairs. A Wicks choir division was added in the next decade.[30]

Another organ subcommittee was formed in 1978 to assess the progress since the mid-century restoration. Its major move was to replace the Wicks choir division, which had never integrated well with the rest of the organ due to a difference in powering methods. It was replaced with a Moller division in 1980. A 1990 committee was able to negotiate another deal with Moller for the completion of the plan.[30]

The next year the Echo organ was removed to make way for the completion of the Moller. The company delivered the final set of pipes and mechanics in late 1991. After they were installed, the expanded organ was rededicated with two recitals in 1992, both including the Toccata. An annual recital series was established that year as well, later with the help of a state grant.[30]

Bell

Church lore has it that the first bell was made from copper and silver brought by congregants as gifts upon the baptism of their children. This bell was replaced with a professionally cast one in 1724, shortly after the second church was expanded. The cost was split between the church and the patent trustees.[9]

That bell lasted until the fire started by the British Army in 1777 damaged the church sufficiently for the bell tower to collapse. A replacement bell donated to the church by a Colonel Rutgers, a friend of the congregation, was not popular, as it sounded more like a ship's bell than a church's. Eventually it was supposedly donated to the courthouse, and Rutgers arranged for the casting of a new bell. The 540-pound (240 kg) replacement was brought over from Amsterdam in 1794.[9]

It remained in regular service, tolling not only for services and funerals but also at noon and 8 p.m. daily, until a crack developed in 1888. After that it was rung only for special events and at the remembrances of recently deceased U.S. presidents, up to Woodrow Wilson's death in 1924.[9]

Only once since then has it been rung. During World War II, it rang in the New Year for 1943. This was broadcast to the Netherlands via shortwave radio. That country was occupied by Nazi Germany at the time, and most of its church bells had been confiscated and melted down for matériel. Those that had not were not permitted to be rung, and the broadcast was thus intended to boost morale among the Dutch population.[9]

After Bethany Chapel burned down following its sale in 1946, the church was able to salvage its 1870 bell from the ruins. It was fully restored in 1974 and is now on display in the church's narthex.[9]

Hobgoblin legend

Church lore has it that a hobgoblin haunts the steeple. The story begins with an early dominie and his wife returning from New York City via the Hudson in stormy weather. As the ship passed Dunderberg Mountain in the Hudson Highlands, the creature flew out and sat on the foremast, making the ship more likely to capsize in the rough water. The passengers and crew asked the dominie to pray.[9]

He did, and the hobgoblin left. The next morning, its cap was discovered hanging on the church's bell tower. In attempting to get it back, the hobgoblin became imprisoned in the tower, and all succeeding spires. He will remain so, the legend says, as long as the church remains on consecrated ground. Stories claim that a small painter has been seen at work on the steeple during lightning flashes. His moans during Sunday services were mistaken for worshippers snoring.[9]

The tale is related in an episode of "Dolph Heyliger," part of Washington Irving's 1822 Bracebridge Hall.

Twice the creature is supposed to have made more direct contact with humans. A painter on the steeple in 1852 died of "painter's colic" when he was scared into a fall off the church, and in 1984 another painter suddenly climbed down after he claimed to have been tapped on the shoulder three times. The hobgoblin is supposed to have added an extra line to the clock face so that "XII" became "XIII".[9]

See also

References

- ↑ "Old Dutch Church staff". Old Dutch Church. 2008. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 William E. Krattinger and James A. Jacobs (May 2006). National Historic Landmark Nomination: First Reformed Protestant Dutch Church of Kingston / Dutch Reformed Church; Old Dutch Church (PDF). National Park Service.

- ↑ "First Reformed Protestant Dutch Church of Kingston". National Park Service. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- ↑ Paul Kirby (October 11, 2008). "Kingston's Old Dutch Church gets national landmark status". Daily Freeman. Retrieved October 14, 2008.

- ↑ "Interior Designates 16 New National Historic Landmarks". D.O.I. News Release. U.S. Department of the Interior. October 14, 2008. Archived from the original on October 20, 2008. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- ↑ "Kingston City Code, Article 1 § 264.5". Ecode. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

Because of the visual importance of the Old Dutch Church Steeple, no new structure may rise within the Stockade Area above the base of the steeple, which is 62 feet above curb level.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Our Story". Old Dutch Church. 2008. Retrieved July 24, 2009.

- ↑ "Kingston's Old Cemetery. Where Lie Buried The Ancestors Of Many A Famous Family". New York Times. June 10, 1894.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Werner, James W. (February 1, 2009). "The Old Dutch Church, Kingston, NY". Retrieved July 29, 2009.

- ↑ Badger, William (Summer 1972). "Historical and Descriptive Data, Reformed Protestant Dutch Church". Historic American Buildings Survey. Library of Congress. p. 1. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

It has some aspects of James Gibbs St.-Martin-in-the-Fields in London

- ↑ "Old Dutch Church Heritage Museum page". Old Dutch Church. Retrieved August 1, 2009.

- ↑ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Langston, Bonnie (February 15, 2009). "Old Dutch Church marks milestone". Daily Freeman. Journal Register Company. Archived from the original on February 20, 2012. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Chronology". Old Dutch Church. Retrieved August 1, 2009.

- ↑ Kingston's Old Dutch Church on shaky ground, but aid may be near recordonline.com

- ↑ "Hinchey Announces Old Dutch Church's Designation as National Historic Landmark" (Press release). Office of U.S. Rep. Maurice Hinchey. October 10, 2008. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

- ↑ "Hinchey Helps Officially Unveil Old Dutch Church as a National Historic Landmark" (Press release). Office of U.S. Rep. Maurice Hinchey. June 14, 2009. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

- ↑ Murphy, Meghan (January 26, 2009). "Kingston's Old Dutch Church celebrating 350 years". Times-Herald Record. Ottaway Community Newspapers. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

- ↑ Horrigan, Jeremiah (September 15, 2010). "Kingston's Old Dutch Church on shaky ground, but aid may be near". Times-Herald Record. News Corporation. Retrieved September 27, 2010.

- ↑ "Mission Statement". Old Dutch Church. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Beliefs". Old Dutch Church. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Sunday Morning Services". Old Dutch Church. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Christian Education". Old Dutch Church. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Women's Ministry". Old Dutch Church. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Men's Club". Old Dutch Church. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ↑ "The Steeple Chimes:Old Dutch Church's Monthly Newsletter". Old Dutch Church. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Friends of Old Dutch". Old Dutch Church. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Kingston Community Singers". Old Dutch Church. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Mendelssohn Club of Kingston". Old Dutch Church. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lottridge, Barbara (1998). "The Moller Organ — Old Dutch Church, Kingston, NY". Central Hudson Valley chapter of American Guild of Organists. Retrieved August 8, 2009.

External links

- Official website

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. NY-5573, "Reformed Protestant Dutch Church, Main Street, Kingston, Ulster County, NY", 8 photos, 2 color transparencies, 10 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- The Old Dutch Church, Kingston, N.Y.

- Old Dutch Organ History at Central Hudson Valley chapter of American Guild of Organists.

- Old Dutch Church birth, marriage and death records