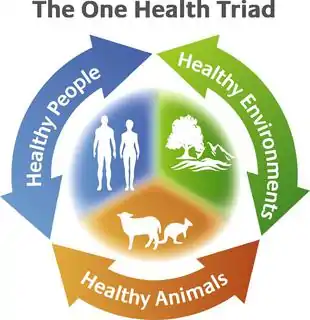

The concept of One Health is the unity of multiple practices that work together locally, nationally, and globally to help achieve optimal health for people, animals, and the environment. When the people, animals, and environment are put together they make up the One Health Triad .[2] The One Health Triad shows how the health of people, animals, and the environment is linked to one another.[2] With One Health being a worldwide concept, it makes it easier to advance health care in the 21st century.[3] When this concept is used, and implied properly it can help protect and save the lives of both people, animals, and the environment in the present and future generations.[3]

Background

The origins of the One Health Model dates as far back as 1821, with the first links between human and animal diseases being recognized by Rudolf Virchow. Virchow noticed links between human and animal disease, coining the term "zoonosis." The major connection Virchow made was between Trichinella spiralis in swine and human infections.[4] It was over a century later before the ideas laid out by Virchow were integrated into a single health model connecting human health with animal health.

In 1964, Dr. Calvin Schwabe, a former member of World Health Organization (WHO) and the founding chair of Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine at the Veterinary School at the University of California Davis, called for a "One Medicine" model emphasizing the need for collaboration between human and wildlife pathologists as a means of controlling and even preventing disease spread.[5] It would be another four decades before the One Health became a reality with the 12 Manhattan Principles, where human and animal pathologists called for "One Health, One World."[5][6]

The One Health Model has gained momentum in recent years due to the discovery of the multiple interconnections that exist between animal and human disease. Recent estimates place zoonotic diseases as the source 60% of total human pathogens, and 75% of emerging human pathogens.[7]

Applying the One Health Model

The One Health Model can constantly be applied with human and animal interactions. One of the main situations where One Health can be applied is with canine and feline obesity being linked to their owners and their own obesity.[8] Obesity in canines and felines is not good for them nor is it good for humans. The obesity of humans and their animals can result in many health problems such as diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis, and many others.[8] In some cases if the obesity of the pet is too bad the pet may be removed from its owner and put up for adoption.[8] The only solution for this issue is to encourage owners to have a healthy lifestyle for both them and their animals.[8] Zoonotic Diseases is another situation that the One Health model can be applied to. This is talked about more in the Zoonotic Disease section.

One Health and Antibiotic Resistance

Antibiotic resistance is becoming a serious problem in today's agriculture industry and for humans. One reason for this occurring resistance is that natural resistomes are present in different environmental niches.[9] These environmental resistomes function as an antibiotic resistance gene.[9] There are many questions and research that needs to be further done to find out if these environmental resistomes play a big role in the antibiotic resistance that is occurring in humans, animals, and plants.[9] A recent study was done and reported that 700 000 annual deaths were caused by infections due to drug resistant pathogens [10] This study also reported that if unchecked, this number will increase to 10 million by 2050.[10] The National Antimicrobial Monitoring System is a system used to monitor antimicrobial resistance among bacteria that is isolated from animals that are used as food[11] In 2013 they found that about 29% of turkeys, 18% of swine, 17% of beef, and 9% of chicken were multi drug resistant, meaning they had resistance to 3 or more classes of antimicrobials.[11] Having this resistance for both animals and humans makes it easier for zoonotic diseases to be transferred between them and also makes it easier for the resistance of these antimicrobials to be passed on.[12] With this being said, there are many possible risk management options that can be taken to help reduce this possibility.[13] Most of these risk management options can take place on the farm or at the slaughter house for animals.[13] When it comes to humans, risk management has to be done by you yourself and you have to be responsible for good hygiene, up to date vaccinations, and proper use of antibiotics.[14][15] With that being said, the same management on farms needs to be taken for proper use of antibiotics and only using them when it is absolutely necessary and improving the general hygiene in all stages of production.[13] With these management factors added in with research and knowledge on the amount of resistance within our environment, antimicrobial resistance may be able to be controlled and help reduce the amount of zoonotic diseases that are passed between animals and humans.[13]

Zoonotic Diseases and One Health

Zoonosis or zoonotic disease can be defined as an infectious disease that can be transmitted between animals and humans.[16] One Health plays a big role in helping to prevent and control zoonotic diseases.[17] Approximately 75% of new and emerging infectious diseases in humans are defined as zoonotic.[17] Zoonotic diseases can be spread in many different ways.[18] The most common known ways they are spread are through direct contact, indirect contact, vector-borne, and food-borne.[18] Below in (Table 1) you can see a list of different zoonotic diseases, their main reservoirs, and their mode of transmission.

Table 1: Zoonotic Diseases

| Disease | Main reservoirs | Usual mode of transmission to humans |

| Anthrax | livestock, wild animals, environment | direct contact, ingestion |

| Animal influenza | livestock, humans | may be reverse zoonosis |

| Avian influenza | poultry, ducks | direct contact |

| Bovine tuberculosis | cattle | milk |

| Brucellosis | cattle, goats, sheep, pigs | dairy products, milk |

| Cat scratch fever | cats | bite, scratch |

| COVID-19 | not yet known | not yet known |

| Cysticercosis | cattle, pigs | meat |

| Cryptosporidiosis | cattle, sheep, pets | water, direct contact |

| Enzootic abortion | farm animals, sheep | direct contact, aerosol |

| Erysipeloid | pigs, fish, environment | direct contact |

| Fish tank granuloma | fish | direct contact, water |

| Campylobacter | poultry, farm animals | raw meat, milk |

| Salmonella | poultry, cattle, sheep, pigs | foodborne |

| Giardiasis | humans, wildlife | waterborne, person to person |

| Glanders | horse, donkey, mule | direct contact |

| Haemorrhagic colitis | ruminants | direct contact (and foodborne) |

| Hantavirus syndromes | rodents | aerosol |

| Hepatitis E | not yet known | not yet known |

| Hydatid disease | dogs, sheep | ingestion of eggs excreted by dog |

| Leptospirosis | rodents, ruminants | infected urine, water |

| Listeriosis | cattle, sheep, soil | dairy produce, meat products |

| Louping ill | sheep, grouse | direct contact, tick bite |

| Lyme disease | ticks, rodents, sheep, deer, small mammals | tick bite |

| Lymphocytic choriomeningitis | rodents | direct contact |

| Orf | sheep | direct contact |

| Pasteurellosis | dogs, cats, many mammals | bite/scratch, direct contact |

| Plague | rats and their fleas | flea bite |

| Psittacosis | birds, poultry, ducks | aerosol, direct contact |

| Q fever | cattle, sheep, goats, cats | aerosol, direct contact, milk, fomites |

| Rabies | dogs, foxes, bats, cats animal | bite |

| Rat bite fever (Haverhill fever) | rats | bite/scratch, milk, water |

| Rift Valley fever | cattle, goats, sheep | direct contact, mosquito bite |

| Ringworm | cats, dogs, cattle, many animal species | direct contact |

| Streptococcal sepsis | pigs | direct contact, meat |

| Streptococcal sepsis | horses, cattle | direct contact, milk |

| Tickborne encephalitis | rodents, small mammals, livestock | tickbite, unpasteurised milk products |

| Toxocariasis | dogs, cats | direct contact |

| Toxoplasmosis | cats, ruminants | ingestion of faecal oocysts, meat |

| Trichinellosis | pigs, wild boar | pork products |

| Tularemia | rabbits, wild animals, environment, ticks | direct contact, aerosol, ticks, inoculation |

| Ebola, Crimean-Congo HF, Lassa and Marburg viruses | variously: rodents, ticks, livestock, primates, bats | direct contact, inoculation, ticks |

| West Nile fever | wild birds, mosquitoes | mosquito bite |

| Zoonotic diphtheria | cattle, farm animals, dogs | direct contact, milk |

See also

References

- ↑ "OPINION: DO WE NEED TO INDUCE STRESS in the ONE-HEALTH PARADIGM?". THE OUTBREAK. 2013-10-16. Retrieved 2017-04-05.

- 1 2 "One Health - It's all connected". avma.org. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- 1 2 "About the One Health Initiative". onehealthinitiative.com. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ Schultz, Myron (2008). "Rudolf Virchow". Emerg Infect Dis. 14 (9): 1480–1481. doi:10.3201/eid1409.086672. PMC 2603088.

- 1 2 "History of One Health". Cdc.gov. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ↑ "The Manhattan Principles As defined during the meeting titled Building Interdisciplinary Bridges to Health in a "Globalized World" held in 2004" (PDF). Cdc.gov. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ↑ "Zoonotic Disease: When Humans and Animals Intersect". Cdc.gov. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Sandoe, Peter (December 20, 2014). "Canine and feline obesity: a One Health perspective" (PDF). Veterinary Record. 175 (24): 610–616. doi:10.1136/vr.g7521. PMID 25523996. S2CID 27828358.

- 1 2 3 Atlans, Ronald M. (2014). One Health: People, Animals, and the Environment. Washington, DC: ASM Press. pp. 185–197. ISBN 978-1-55581-842-5.

- 1 2 Robinson, T.P. (5 August 2016). "Antibiotic resistance is the quintessential One Health issue". Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 110 (7): 377–380. doi:10.1093/trstmh/trw048. PMC 4975175. PMID 27475987 – via Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 "About Antibiotic Resistance and One Health Antibiotic Stewardship". Minnesota Department of Health. 30 March 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ Antimicrobial Resistance in Zoonotic Bacteria and Foodborne Pathogens. Washington, DC: American Society For Microbiology. 2008. pp. 12–13.

- 1 2 3 4 Choffnes, Eileen R. (2012). Improving Food Safety Through a One Health Approach: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. pp. A15. ISBN 978-0-309-25933-0.

- ↑ Editor., Nyhus, Philip J., Contribution by. McCarthy, Tom, Volume Editor. Mallon, David, Volume (June 2016). Snow Leopards: Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes. Academic Press [Imprint]. ISBN 978-0-12-802213-9. OCLC 972571184.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Canada, Public Health Agency of. "Prevention of antibiotic resistance - Canada.ca". www.canada.ca. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- ↑ "Zoonotic Diseases: Disease Transmitted from Animals to Humans - Minnesota Dept. of Health". www.health.state.mn.us. Retrieved 2017-04-05.

- 1 2 Bidaisee, Satesh; Macpherson, Calum N. L. (2014-01-01). "Zoonoses and One Health: A Review of the Literature". Journal of Parasitology Research. 2014: 874345. doi:10.1155/2014/874345. ISSN 2090-0023. PMC 3928857. PMID 24634782.

- 1 2 "Zoonotic Diseases One Health CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-05.

- ↑ "List of zoonotic diseases - GOV.UK". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 2017-04-05.