Open ocean convection is a process in which the mesoscale ocean circulation and large, strong winds mix layers of water at different depths. Fresher water lying over the saltier or warmer over the colder leads to the stratification of water, or its separation into layers. Strong winds cause evaporation, so the ocean surface cools, weakening the stratification. As a result, the surface waters are overturned and sink while the "warmer" waters rise to the surface, starting the process of convection. This process has a crucial role in the formation of both bottom and intermediate water and in the large-scale thermohaline circulation, which largely determines global climate.[1] It is also an important phenomena that controls the intensity of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC).[2]

Convection exists under certain conditions which are promoted by strong atmospheric forcing due to thermal or haline surface fluxes. This may be observed in oceans adjacent to boundaries with either dry and cold winds above or ice, inducing large latent heat and moisture fluxes. Ocean convection depends on the weakness of stratification under the surface mixed layer. These stratified water layers must rise, near to the surface resulting in their direct exposition to intense surface forcing.[1][3]

Major convection sites

Deep convection is observed in the subpolar North Atlantic (the Greenland Sea and the Labrador Sea), in the Weddell Sea in the southern hemisphere as well as in the northwestern Mediterranean. In sub-polar regions, the upper mixed layer starts deepening during late autumn until early spring, when the convection is at the deepest level before the phenomenon is weakened.[2]

The weak density stratification of the Labrador Sea is observed each wintertime, in depths between 1000 and 2000 m, making it one of the most extreme ocean convection sites in the world. The deep convection in the Labrador Sea is significantly affected by the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). In winter, when the NAO is in positive phase above this region, the cyclonic activity is greater over the North Atlantic with an enhanced circulation of cold and dry air. During this positive phase of NAO, the oceanic heat loss from the Labrador Sea is higher, contributing to a deeper convection.[3] According to Holdsworth et al. (2015), during the negative phase of NAO which is associated with an absence of high frequency forcing, the average maximum mixed layer depth decreases more than 20%.[4]

The Greenland Sea differs from the Labrador Sea because of the important role of ice in preconditioning during the months November until February. In early winter, the ice spreads eastward across the central Greenland Sea, and brine rejection under the ice increases the surface layer density. In March, when preconditioning is far enough advanced, and the meteorological conditions are favourable, deep convection develops.[5]

In the northwestern Mediterranean Sea, deep convection occurs in winter, when the water undergoes the necessary preconditioning with air-sea fluxes inducing buoyancy losses at the surface. In winter, the Gulf of Lions is regularly subject to atmospheric forcing under the intense cold winds Tramontane and Mistral, inducing strong evaporation and an intense cooling of surface waters. This leads to buoyancy losses and vertical deep mixing.[6]

The convection in the Weddell Sea is mostly associated with polynya. According to Akitomo et al. (1995), Arnold L. Gordon was the first to find the remnant of deep convection near the Maud Rise in 1977. This deep convection was probably accompanied by a large polynya which had been appearing in the central Weddell Sea every winter during 1974-76.[7] Additionally, according to Van Westen and Dijkstra, (2020), the formation of Maude Rise polynya which was observed in 2016 is associated with the subsurface convection. In particular, the Maud Rise region undergoes preconditioning due to the accumulation of subsurface heat and salt, leading to a convection and favoring a polynya formation.[8]

Phases of convection

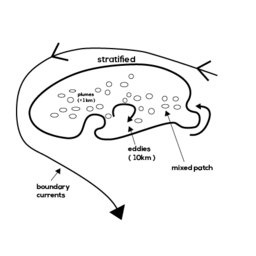

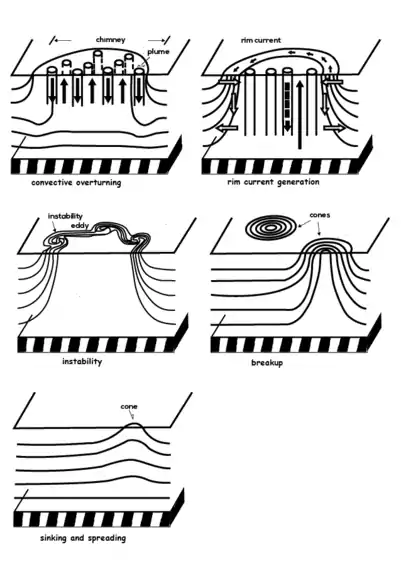

Ocean convection is distinguished by three phases: preconditioning, deep convection and lateral exchange and spreading. Preconditioning is referred to a period during which a cyclonic gyre-scale circulation and buoyancy forcing are combined to predispose a convective site to locally overturn. A site is preconditioned when a laterally extended deep region of relatively weak vertical density stratification exists there, and it is capped by a locally shallow thermocline. Cooling events lead to the second phase, deep convection, in which a part of the fluid column may overturn in numerous plumes that distribute the dense surface water in the vertical axis. These plumes form a homogeneous deep chimney. During this phase, the chimney is getting deeper through plume-scale overturning and adjusts geostrophically. Additionally, at some point in time, the sea-surface buoyancy loss is completely offset through lateral buoyancy transfer by baroclinic eddies which are generated at the periphery of the convective regime and thus, the quasi-steady state can be achieved. Once the surface forcing decreases, the vertical heat transfer due to convection abates, leading to horizontal transfer associated with eddying on geostrophic scale. The balance between sea-surface forcing and lateral eddy buoyancy flux becomes unstable. Due to gravity and planetary rotation, the mixed fluid disperses and spreads out, leading to the decay of the chimney. The residual pieces of the “broken” chimney are named cones. The lateral exchange and spreading are also known as restratification phase. If surface conditions deteriorate again, deep convection can reinitiate while the remaining cones can form preferential centers for further deep convective activity.[3][9][10]

Phenomena involved in convection

Deep convection is distinguished in small-scale and mesoscale processes. Plumes represent the smallest-scale process while chimneys (patch) and eddies represent the mesoscale.[11]

Plumes

Plumes are the initial convectively driven vertical motions which are formed during the second phase of convection. They have horizontal scales between 100m and 1 km and their vertical scale is around 1–2 km with vertical velocities of up to 10 cm/s which are measured by acoustic doppler current profilers (ADCPs). Time scales associated with convective plumes are reported to be several hours to several days.[3][11][12]

The plumes act as “conduits” or as “mixing agents” in terms of their dynamic part. If they act as “conduits”, they transport cooled and dense surface water downward. This is the main mechanism of water transport toward lower depths and its renewal. However, plumes can act as “mixing agents” rather than as downward carriers of a flow. In this case, the convection cools and mixes a patch of water, creating a dense homogeneous cylinder, like a chimney, which ultimately collapses and adjusts under planetary rotation and gravity.[13]

Coriolis force and thermobaricity are important in deep convective plumes. Thermobaricity is the effect in which sinking cold saline water is formed under freezing conditions, resulting in downward acceleration. Additionally, many numerical and tank modeling experiments examine the role of rotation in the processes of the convection and in the morphology of the plumes. According to Paluszkiewicz et al. (1994), planetary rotation does not affect the individual plumes vertically, but do so horizontally. Under the influence of rotation, the diameter of the plumes becomes smaller compared to the diameter of the plumes in the absence of rotation. In contrast, chimneys and associated eddies are dominated by the effects of rotation due to thermal wind.[11]

Convection patch (or “Chimney”)

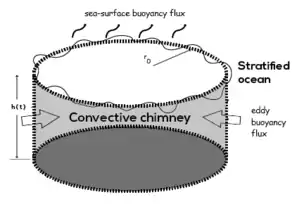

The convective overturning of the water column occurs through a contribution of a high number of intense plumes, which strongly mix the column. The plumes can process large volumes of fluid to form what has become known as a “chimney” of homogenized fluid.[14] These vertically isolated homogenized water columns have a diameter of 10 to 50 km and they are 1–2 km deep. Surface waters growing denser and sinking drive the initial deepening stage, while the final deepening stage and the restratification phase are affected by a buoyancy transfer, through the lateral surface of the chimney, by baroclinic eddies.[2]

Seasonality

The chimneys of deep convection remain open for one to three months, during winter, in a quasi-stable state whereas they can collapse within a few weeks. The chimneys are destroyed in early spring when the sea-surface buoyancy flux weakens and reverses while the stratification of the water’s layers under the mixed layer starts becoming stable.[2]

Formation

Formation of the convection chimneys is preconditioned by two processes: strong heat fluxes from the sea-surface and cyclonic circulation. A chimney is formed when a relatively strong buoyancy flux from the ocean’s surface exists for at least 1 to 3 days. The time, depth and diameter development of the chimney clearly depends on the buoyancy flux and the stratification of the surrounding ocean.[2] As the surface water cools, it becomes denser and it overturns, forming a convectively modified layer of depth . In the center of the chimney, the mixed layer deepens and the depth as a function of time is computed as described below.

During the initial stage of the intensive deepening of the chimney, when the baroclinic instability effects are assumed to be unimportant, the depth can be found as a function of time using the buoyancy forcing. The buoyancy is defined as:

Where is the acceleration due to gravity, the potential density and a constant reference value of density. The buoyancy equation for the mixed layer is:

Where is the buoyancy and the buoyancy forcing. The buoyancy forcing is equal to where is the buoyancy loss. As a simplification, the assumption that the buoyancy loss is constant in time () is used. Neglecting horizontal advection and integrating the above equation over the mixed layer, we obtain:

For a uniformly stratified fluid, the power of the buoyancy frequency is equal to:

Therefore, the classical result for the nonpenetrative deepening of the upper mixed layer is:[14]

The chimney evolution equation

As time progresses and the baroclinic instability effects are becoming important, the time evolution of the chimney cannot be described only by the buoyancy forcing. The maximum depth that a convection chimney reaches, must be found using the chimney evolution equation instead. Following Kovalevsky et al. (2020) and Visbeck et al. (1996), consider a chimney of radius and a time-dependent height . The driving force of the chimney deepening is the surface buoyancy loss which causes convective overturning leading to homogeneously mixed fluid in the interior of the chimney. Assuming that the density at the base of the chimney is continuous, the buoyancy anomaly of a particle which is displaced a distance Δz within the chimney is:

According to Kovalevsky et al. (2020) the buoyancy budget equation is:[2]

The left-hand side represents the time evolution of the total buoyancy anomaly accumulated in the time-depended chimney volume . The first and second term on the right-hand side correspond to the total buoyancy loss from the sea-surface over the chimney and the buoyancy transfer between the interior of the chimney and the baroclinic eddies, respectively.[2]

Initially, the total buoyancy depends only on the total buoyancy loss through the sea-surface above the chimney. While time progresses, the buoyancy loss through the sea-surface above the chimney becomes partially equivalent with the lateral buoyancy exchange between the chimney and the baroclinic eddies, through the chimney’s side walls.[2]

Visbeck et al. (1996), by using a suggestion by Green (1970) and Stone (1972), parameterized the eddy flux as:

Where is a constant of proportionality to be determined by observations and laboratory modeling. The variable represents the pulsations of the horizontal current velocity component perpendicular to the side-walls of the chimney while, by following Visbeck et al. (1996), is equal to:[2]

Decay

If the buoyancy loss is maintained for a sufficient time period, then the sea-surface cooling weakens and the restratification phase starts. At the surrounding of the convective regime, the stratification takes up an ambient value while in the center of the chimney the stratification is eroded away. As a result, around the periphery of the chimney, the isopycnal surfaces deviate from their resting level, tilting towards the ocean’s surface. Associated with the tilting isopycnal surfaces a thermal wind is set up generating the rim current around the edge of the convection regime. This current must be in thermal wind balance with the density gradient between the chimney’s interior and exterior. The width of the rim current’s region and its baroclinic zone will initially be of the order of the Rossby radius of deformation.[12][14]

The existence of the rim current plays an important role for the chimney’s collapse. At the center of the chimney, the mixed layer will deepen as , until the growing baroclinic instability begins to carry convected fluid outward while water from the exterior flows into the chimney. At this moment, the rim current around the cooling region becomes baroclinically unstable and the buoyancy laterally is transferred by the instability eddies. If the eddies are intense enough, deepening of the chimney will be limited. In this limit, when the lateral buoyancy flux completely balances the sea-surface buoyancy loss, a quasi-steady state can be established:[2][14]

By solving the above equation, the final depth of the convective chimney can be found to be:

Consequently, the final mixing depth depends on the strength of the cooling, the radius of the cooling and the stratification. Therefore, the final mixing depth is not directly dependent of the rate of the rotation. However, baroclinic instability is a consequence of the thermal wind, which is crucially dependent on rotation.[14] The length scale of baroclinic eddies, assumed to be set by the Rossby radius of deformation, scale as:[14]

Which does depend on the rate of rotation f but is independent of the ambient stratification.

The least time that the chimney needs to reach the quasi-equilibrium state is equivalent with the time that it needs to reach the depth and it is equal to:[14]

The final timescale is independent of the rate of rotation, increases with the radius of the cooling region r and decreases with the surface buoyancy flux Bo. According to Visbeck at al. (1996), the constant of proportionality γ and β are found to be equal to 3.9 ± 0.9 and 12 ± 3 respectively, through laboratory experiments.[14]

Cones

Finally, the cooling of the surface as well as convective activity cease. Therefore, the chimney of homogenized cold water erodes into several small conical structures, named cones, which propagate outward. The cones travel outward, carrying cold water far from the area of cooling. As time progresses and the cones disperse, the magnitude of the rim current diminishes. The currents associated with the cones are intensified and cyclonic at the surface whereas they are weaker and anticyclonic at low depths.[15]

Effects of global warming on ocean convection

Deep convective activity in the Labrador Sea has decreased and become shallower since the beginning of the 20th century due to low-frequency variability of the North Atlantic oscillation. A warmer atmosphere warms the surface waters so that they do not sink to mix with the colder waters below. The resulting decline does not occur steeply but stepwise. Specifically, two severe drops in deep convective activity have been recorded, during the 1920s and the 1990s.[16]

Similarly, in the Greenland Sea, shallower deep mixed layers have been observed over the last 30 years due to the fall of wintertime atmospheric forcing. The melting of the Greenland ice-sheet, could also contribute to an even earlier extinction of deep convection. The freshening of the surface waters due to enhanced meltwater from the Greenland Ice Sheet, have less density, making it more difficult for oceanic convection to occur.[17] Reduction of the deep wintertime convective mixing in the North Atlantic results the weakening of AMOC.

References

- 1 2 Wadhams, P.; Holfort, J.; Hansen, E.; Wilkinson, J. P. (2002). "A deep convective chimney in the winter greenland sea". Geophysical Research Letters. 29 (10): 76–1–76-4. Bibcode:2002GeoRL..29.1434W. doi:10.1029/2001GL014306. ISSN 1944-8007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Kovalevsky, D. V; Bashmachnikov, I. L.; Alekseev, G. V. (2020). "Formation and decay of a deep convective chimney". Ocean Modelling. 148: 101583. Bibcode:2020OcMod.14801583K. doi:10.1016/j.ocemod.2020.101583. ISSN 1463-5003.

- 1 2 3 4 The Lab Sea, Group (1998). "The Labrador Sea Deep Convection Experiment". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 79 (10): 2033–2058. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1998)079<2033:TLSDCE>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0003-0007. S2CID 128525901.

- ↑ Holdsworth, Amber M.; Myers, Paul G. (2015-06-15). "The Influence of High-Frequency Atmospheric Forcing on the Circulation and Deep Convection of the Labrador Sea". Journal of Climate. 28 (12): 4980–4996. Bibcode:2015JCli...28.4980H. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00564.1. ISSN 0894-8755.

- ↑ Schott, F.; Visbeck, M.; Send, U. (1994), Malanotte-Rizzoli, Paola; Robinson, Allan R. (eds.), "Open Ocean Deep Convection, Mediterranean and Greenland Seas", Ocean Processes in Climate Dynamics: Global and Mediterranean Examples, NATO ASI Series, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 203–225, doi:10.1007/978-94-011-0870-6_9, ISBN 978-94-011-0870-6, retrieved 2021-05-07

- ↑ Margirier, Félix; Bosse, Anthony; Testor, Pierre; L'Hévéder, Blandine; Mortier, Laurent; Smeed, David (2017). "Characterization of Convective Plumes Associated With Oceanic Deep Convection in the Northwestern Mediterranean From High-Resolution In Situ Data Collected by Gliders". Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 122 (12): 9814–9826. Bibcode:2017JGRC..122.9814M. doi:10.1002/2016JC012633. ISSN 2169-9291. S2CID 134732376.

- ↑ Akitomo, K.; Awaji, T.; Imasato, N. (1995). "Open-ocean deep convection in the Weddell Sea: two-dimensional numerical experiments with a nonhydrostatic model". Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. 42 (1): 53–73. Bibcode:1995DSRI...42...53A. doi:10.1016/0967-0637(94)00035-Q. ISSN 0967-0637.

- ↑ Van Westen, R. M.; Dijkstra, H. A. (2020). "Subsurface Initiation of Deep Convection near Maud Rise" (PDF). Ocean Science Discussions: 1–15.

- ↑ Jones, Helen. "Open-ocean deep convection". puddle.mit.edu. Retrieved 2021-05-07.

- ↑ Marshall, John; Schott, Friedrich (February 1999). "Open-ocean convection: Observations, theory, and models". Reviews of Geophysics. 37 (1): 1–64. Bibcode:1999RvGeo..37....1M. doi:10.1029/98RG02739.

- 1 2 3 Paluszkiewicz, T.; Garwood, R. W.; Denbo, Donald W. (1994). "Deep Convective Plumes in the Ocean". Oceanography. 7 (2): 34–44. doi:10.5670/oceanog.1994.01.

- 1 2 Paluszkiewicz, T.; Romea, R. D. (1997). "A one-dimensional model for the parameterization of deep convection in the ocean". Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans. 26 (2): 95–130. Bibcode:1997DyAtO..26...95P. doi:10.1016/S0377-0265(96)00482-4. ISSN 0377-0265.

- ↑ Send, Uwe; Marshall, John (1995). "Integral Effects of Deep Convection". Journal of Physical Oceanography. 25 (5): 855–872. Bibcode:1995JPO....25..855S. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(1995)025<0855:IEODC>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-3670.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Visbeck, Martin; Marshall, John; Jones, Helen (1996). "Dynamics of Isolated Convective Regions in the Ocean". Journal of Physical Oceanography. 26 (9): 1721–1734. Bibcode:1996JPO....26.1721V. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(1996)026<1721:DOICRI>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-3670.

- ↑ Jones, Helen; Marshall, John (1993). "Convection with Rotation in a Neutral Ocean: A Study of Open-Ocean Deep Convection". Journal of Physical Oceanography. 23 (6): 1009–1039. Bibcode:1993JPO....23.1009J. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(1993)023<1009:CWRIAN>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-3670.

- ↑ Brodeau, Laurent; Koenigk, Torben (2016-05-01). "Extinction of the northern oceanic deep convection in an ensemble of climate model simulations of the 20th and 21st centuries". Climate Dynamics. 46 (9): 2863–2882. Bibcode:2016ClDy...46.2863B. doi:10.1007/s00382-015-2736-5. ISSN 1432-0894. S2CID 73579392.

- ↑ Moore, G. W. K.; Våge, K.; Pickart, R. S.; Renfrew, I. A (2015). "Decreasing intensity of open-ocean convection in the Greenland and Iceland seas" (PDF). Nature Climate Change. 5 (9): 877–882. Bibcode:2015NatCC...5..877M. doi:10.1038/nclimate2688. hdl:1956/16722.

Other sources

- Marshall, J.; Schott, F. (1999). "Open‐ocean convection: Observations, theory, and models". Reviews of Geophysics. 37 (1): 1–64. Bibcode:1999RvGeo..37....1M. doi:10.1029/98RG02739.

- Lazier, J.; Hendry, R.; Clarke, A.; Yashayaev, I.; Rhines, P. (2002). "Convection and restratification in the Labrador Sea". Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. 49 (10): 1819–1835. doi:10.1016/S0967-0637(02)00064-X.