| Operation Golden Fleece | |

|---|---|

| Part of War in Abkhazia (1992–1993) | |

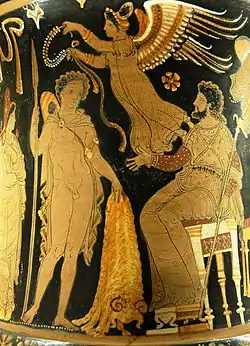

Jason holding the Golden Fleece | |

| Type | Noncombatant Evacuation Operation |

| Location | 43°00′12″N 41°00′55″E / 43.00333°N 41.01528°E |

| Commanded by | Vasilis Ntertilis |

| Objective | Evacuate ethnic Greeks from Abkhazia |

| Date | 15–18 August 1993 |

| Executed by | |

| Outcome | Evacuation of 1,013 civilians |

| Casualties | 0 |

Sukhumi | |

The Operation Golden Fleece (Greek: Επιχείρηση Χρυσόμαλλο Δέρας) codename given to the non-combatant evacuation operation of ethnic Greeks from the port of Sukhumi, Abkhazia. On 14 August 1992, Georgian troops invaded Abkhazia in order to crush its secessionist movement. The war created an atmosphere of lawlessness in the region, resulting in dozens of deaths of Greek civilians. The Greek state decided to intervene in order to evacuate members of the Greek minority in Abkhazia. The operation was carried out by the Hellenic Navy between 15-18 August 1993. It resulted in the evacuation of 1,013 civilians to Alexandroupolis, Greece.

Background

Greek ties with the Black Sea region date back to antiquity, as exemplified by the myths of Prometheus and the Argonauts’ quest to retrieve the Golden Fleece. During the second Greek colonization period (7th – 6th centuries BC), they founded 60 colonies on the Black Sea coast,[1] hellenizing some native populations.[2] Greek immigration to the territory of present day Georgia continued in waves throughout the centuries most notably after the Fall of Constantinople, the Treaty of Adrianople (1829) and in the aftermath of the Greek genocide.[3]

Following the victory of the alliance of Georgian nationalist parties Round Table—Free Georgia in the 1990 Georgian Supreme Soviet election; the Supreme Soviet declared the independence of Georgia from the Soviet Union on 9 April 1991. The leader of Round Table—Free Georgia Zviad Gamsakhurdia was elected president of Georgia in May 1991. Gamsakhurdia's authoritarian ruling style alienated a fraction of the members of his coalition, while his chauvinist and nationalist rhetoric caused discontent in Abkhazia and South Ossetia.[4] By September, clashes had begun to take place between state troops on one side and anti-Gamsakhurdia militias and rebel elements of the National Guard of Georgia on the other. On 22 December, rebel elements of the National Guard led by Tengiz Kitovani assaulted the National Assembly complex in Tbilisi where Gamsakhurdia had barricaded himself; marking the beginning of the Georgian Civil War.[5]

The Abkhaz ASSR was an autonomous region on the north western edge of Georgia. Multi ethnic in its composition, until the 1930s in had an approximately even population of Georgians, Abkhazians, Russians, Greeks and Armenians. In 1949, Soviet authorities forcibly transferred citizens of the Abhaz ASSR they deemed disloyal to the Asian parts of the country. This was followed by the resettlement of Abkhazia by ethnic Georgians, who came to form 45% of the region's population. In August 1992, the Greek minority in Abkhazia numbered 15,000 people most of whom were returnees of the 1949 deportation of the Soviet Greeks.[6]

Ethnic tensions between Abkhazians and Georgians flared up in the aftermath opening of a branch of Tbilisi State University in Sukhumi, which resulted in the 1989 Sukhumi riots. The following year the majority of the non-Georgian members of the Supreme Soviet of Abkhazia declared Abkhazia's sovereignty.[7] The outbreak of civil war in Georgia emboldened Abkhazian separatists even further. In July 1992, the Abkhazian Supreme Council restored the 1925 Abkhazian constitution, effectively declaring sovereignty from Georgia. On 14 August 1992, Georgian troops invaded Abkhazia in response to a draft treaty prepared by the Abkhazian parliament which they saw a paving the way for complete secession.[8]

Prelude

By 18 August 1992, the Georgian army had conquered a large part of Abkhazia including Sukhumi. The Abkhazian separatist government was forced to evacuate to Gudauta.[9] While Abkhazians comprised only 17.8% of the population Gamsakhurdia's nationalist policies[7] largely caused other minority populations to rally behind them. They had also gained the support of militants from the Confederation of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus.[10] The war created an atmosphere of lawlessness in the region. Refugees reported that artillery bombardments had damaged housing while groups of bandits, rogue Georgian and Abkhazian soldiers operated with impunity. These criminal elements engaged in the robbery, murder and rape of civilians and ejected them from their houses.[11] Russia and Israel immediately launched non-combatant evacuation operations for the members of their respective minorities. The first Greek refugees fled to former Soviet states, mainly to southern Russia and then tried to immigrate to Greece either legally or via travel visas.[12]

During the Cold War Greek foreign policy was focused on the Cyprus problem and its relations with its Balkan neighbors, while the Black Sea region was largely ignored.[13] The Greek state failed to react to the unfolding situation in a timely manner. Greek immigration authorities arrested and even deported refugees citing the fact that their residence permits had expired. On 1 November, refugee organizations sent a protest note to the Greek government demanding the evacuation of ethnic Greek civilians from Abkhazia and the legalization of arriving refugees.[14] Pontic Greek organizations likewise launched demonstrations in Athens and Thessaloniki and petitioned Konstantinos Mitsotakis’ government to evacuate the members of Greek community from Abkhazia. The largest demonstration took place in central Athens in April 1993 and involved 5000 protesters.[15][16]

During the course of the Georgian occupation of Sukhumi 30 Greeks were killed by paramilitary organizations and 22 died as a result of artillery bombardments. Total Greek casualties across Abkhazia during the course of the entire war may number over 200 dead according to verbal statements from refugees.[17]

Operation

In July 1993, Greek deputy Foreign Minister Virginia Tsouderou ordered the evacuation of ethnic Greeks from Abkhazia. On 21 July, a diplomatic task force which included military attaché Colonel Georgios Kousoulis traveled from the Embassy of Greece, Moscow to Tbilisi and began planning Operation Golden Fleece. The decision was taken for the task force to travel to Sukhumi and coordinate the evacuation with the local Greek community and to expedite the process of issuing Greek identity cards and exit permits to the evacuees. Fighting in the vicinity of Sukhumi prevented the diplomats from immediately proceed to their destination. They therefore visited Adjara and spoke with the head of the Greek community in Sochi, handing over documents to refugees who had fled to the two regions. On 31 July, the task force reached Sukhumi and established its headquarters in an inn guarded by α Russian paratrooper battalion.[18]

An improvised embassy was established in a house in the center of the city. Greek diplomats then visited all the suburbs of Sukhumi and seven surrounding villages under an armed convoy of Georgian policemen. The task force collected the necessary documents to issue identity cards and surveyed the port to facilitate the evacuation. Power cuts and a night curfew, complicated the operation and forced the Greek officials to work under candle light. On 9 August, Russian diplomats assured the Greek side that the paratroopers would assist in the evacuation if necessary.[19] The same day the private ferry Viscountes M. departed from the port of Piraeus for Sukhumi.[20] Its civilian crew was supplemented by 20 soldiers from the Underwater Demolition Command, two Hellenic Navy doctors and three nurses dressed in civilian clothing.[21] [22] On 12 August, 11 Greek military policemen led by Captain Vasilis Ntertilis (who had overall command of the operation) arrived in Sukhumi from Georgia and finalized the evacuation plan which was approved by Georgian authorities.[23]

At some point Viscountes M. was stopped by an Abkhazian improvised patrol boat whose crew boarded her. After brief negotiation and a bribe of cigarettes the rebels allowed the ship to continue to its destination.[21] At 5 am on 15 August,[24] the military police team secured the only entrance to the harbor. Viscountes M. anchored in the port of Sukhumi several hours later. After unloading humanitarian aid its crew began processing the refugees, who had gathered in the harbor.[22] Greek navy personnel had to intervene multiple times to verbally drive away unidentified armed men present in the harbor who tried to meddle into the crowd of the evacuees.[21] By 17:00 pm, total of 1,013 people boarded the ship which departed for Greece an hour later. No casualties were reported during the course of the operation.[22] Gunshots and grenade explosions were heard by the ship's crew shortly after its departure.[20] Viscountes M. reached Alexandroupolis, Greece on 18 August where all the refugees disembarked.[20]

Aftermath

Some 1,484[24] Greeks chose not to take part in the evacuation either because they believed that hostilities were on the verge of ending or because they did not wish to abandon their properties. They either remained in Abkhazia or were temporarily displaced to Georgia and Russia.[15] On 27 September 1993, Sukhumi was captured by the Abkhazians leading to heavy civilian casualties;[24] including victims from the Greek minority. After the fall of Sukhumi Abhazian president Vladislav Ardzinba called upon the refugees to return and "help rebuild the country", he also appointed two ethnic Greeks into his cabinet of ministers.[25]

References

- ↑ Kotsionis 2006, p. 267.

- ↑ Karagiannis 2013, pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Kotsionis 2006, p. 268.

- ↑ Kotsionis 2006, pp. 271–272.

- ↑ O'Ballance 1996, pp. 106–108.

- ↑ Kotsionis 2006, pp. 272–273.

- 1 2 O'Ballance 1996, pp. 102–103.

- ↑ Kalamvrezos 2015, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Kalamvrezos 2015, p. 112.

- ↑ Kotsionis 2006, p. 273.

- ↑ Kalamvrezos 1997, p. 253.

- ↑ Agtzidis 1993, pp. 8, 5.

- ↑ Karagiannis 2013, p. 79.

- ↑ Agtzidis 1993, pp. 5–6.

- 1 2 Agtzidis 1993, p. 8.

- ↑ Karagiannis 2013, p. 86.

- ↑ Agtzidis 1993, p. 21.

- ↑ Kalamvrezos 1997, pp. 254–255.

- ↑ Kalamvrezos 1997, pp. 256–257.

- 1 2 3 CNN (16 November 2021). "Πέθανε ο Γιώργος Σαμιωτάκης, ο καπετάνιος της επιχείρησης «Χρυσόμαλλο Δέρας»" [Giorgos Samiotakis has passed away, the captain of operation "Golden Fleece"] (in Greek). CNN. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - 1 2 3 Papahelas, Alexis (7 March 2022). "Επιχείρηση «Χρυσόμαλλο Δέρας»: Η απομάκρυνση των Ελλήνων της Αμπχαζίας" [Operation "Golden Fleece": The evacuation of the Greeks of Abkhazia] (in Greek). Kathimerini. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- 1 2 3 Kalamvrezos 1997, p. 258.

- ↑ Kalamvrezos 1997, p. 257.

- 1 2 3 Kalamvrezos, Dionysios (19 August 2023). "Επιχείρηση «Χρυσόμαλλο Δέρας»: Η ναυτική «εκστρατεία» στην Αμπχαζία" [Operation "Golden Fleece": The naval "campaign" in Abkhazia] (in Greek). Kathimerini. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ↑ Agtzidis 1993, p. 13.

Sources

- Agtzidis, Vlasis (1993). Ο πόλεμος στην Αμπχαζία και οι συνέπειές του στην ελληνική κοινότητα [The war in Abkhazia and its consequences on the Greek community]. Athens: Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs Report.

- Kalamvrezos, Dionysios (1997). "Μικρό Χρονικό της Επιχείρησης Χρυσόμαλλο Δέρας" [A Short Chronicle of the Operation Golden Fleece]. In Agtzidis, Vlasis (ed.). Οι Άγνωστοι Έλληνες του Πόντου [The Unknown Greeks of Pontus] (in Greek). Etairia Meletis Ellinikis Istorias. pp. 253–259. ISBN 9788888883557.

- Kalamvrezos, Dionysios (2015). Ο ελληνισμός και οι εξελίξεις στη Ρωσία και στις άλλες χώρες της τ. ΕΣΣΔ μετά το 1991: κρίσεις, ελληνικές παρεμβάσεις, προοπτικές [The greek diaspora in Russia and other countries of the former USSR after 1991: crises, greek policies, prospects] (PhD thesis) (in Greek). National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. pp. 1–626. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- Karagiannis, Emmanuel (2013). "Greek Foreign Policy toward the Black Sea Region: Combining Hard and Soft Power" (PDF). Mediterranean Quarterly. 24 (3): 74–101. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- Kotsionis, Panagiotis (2006). Λαοί και πολιτισμοί στην πρώην Σοβιετική ένωση. Η Ελληνική Παρουσία [People and Cultures in the former Soviet Union. The Greek Presence] (in Greek). Athens: typothito - Giorgos Dardanos. ISBN 960-8041-04-X.

- O'Ballance, Edgar (1996). Wars in the Caucasus, 1990-95. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0333671009.