| Battle of Chawinda | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 | |||||||

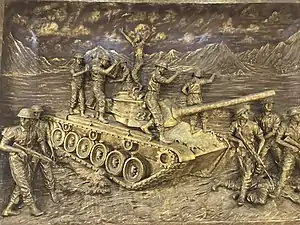

Sculpture showing the Indo-Pakistani War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Pakistan's I Corps Cavalry units:

|

India's I Corps Cavalry units:[7][8]

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

Chawinda Location of Chawinda in Pakistani Punjab | |||||||

The Battle of Chawinda was a major engagement between Pakistan and India in the Second Kashmir War[lower-alpha 2] as part of the Sialkot campaign. It is well known as being one of the largest tank battles in history since the Battle of Kursk, which was fought between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany in World War II.[14]

The initial clashes in Chawinda coincided with the Battle of Phillora, and the fighting here intensified once the Pakistani forces at Phillora retreated. The battle came to an end shortly before the United Nations Security Council mandated an immediate ceasefire, which would formally end the hostilities of the 1965 war.[15][16]

Sialkot campaign

The Sialkot campaign was part of the strategy of riposte that India had devised to counter Pakistan's advances into Jammu and Kashmir (J&K).[10] It called for relieving Jammu by advancing from either Samba (in J&K) or Dera Baba Nanak (in Indian Punjab) with a view to encircling the city of Sialkot along the Marala–Ravi Link Canal (MRL).[17][18][lower-alpha 3]

The canal starts from the Marala Headworks on the Chenab River close to Pakistan's border with J&K, and runs to the west and south of Sialkot, eventually draining into the Ravi River near the town of Narang Mandi.

The GOC Western Command Gen. Harbakhsh Singh favoured launching the campaign from Dera Baba Nanak using the 1st Armoured Division. But he was overridden by the Chief of Army Staff Gen. J. N. Chaudhuri, who created a new I Corps under the command of Lt. Gen. Pat Dunn for the purpose. It would operate from Samba.[22]

Gen. Dunn was given an assortment of units. In addition to the 1st Armoured Division under Maj. Gen. Rajinder Singh, he had:[23][24]

- the 6th Mountain Division under Maj. Gen. S. K. Korla

- the 14th Infantry Division under Maj. Gen. Ranjeet Singh and

- the 26th Infantry Division under Maj. Gen. M. L. Thapan.

The new corps was still in the process of formation when the hostilities broke out in September 1965. Some of the units were also under-strength because of their forces being tied up elsewhere.[25] According to the Indian official history, the force contained 11 infantry brigades and 6 tank regiments.[26][lower-alpha 4]

Pakistani defence

The Pakistani forces opposing the Indian thrust were part of Pakistan's I Corps under Lt. Gen. Bakhtiar Rana. Included in it were:[27]

- the 6th Armoured Division commanded by Maj. Gen. Abrar Hussain,

- the 4th Artillery Corps under Brig. Amjad Ali Khan Chaudhury (affiliated to the 6th Armoured Division), and

- the 15th Infantry Division under Brig. S. M. Ismail.

The 15th Infantry Division was a mixed infantry and armour force, with four pairs of a brigade and an armoured regiment each. However, only one out of the four pairs (the 24th Brigade and 25th Cavalry) was in the conflict area when the Indian campaign started.[27] They were based in and around Chawinda. The 24th Brigade was commanded by Brig. Abdul Ali Malik and the 25th Cavalry was led by Lt. Col. Nisar Ahmed Khan.[28]

The 6th Armoured Division, normally based at Gujranwala, was moved to Pasrur in preparation for the war.[29] It had three cavalry regiments: 10th Cavalry (also called the Guides Cavalry), the 22nd Cavalry and the 11th Cavalry.[30][31] The 11th Cavalry, along with the 4th Artillery Corps, was in Chamb as part of Operation Grand Slam when the operations started. The units were recalled and deployed in the vicinity of Phillora by 8 September.

Later reinforcements included the 8th Infantry Division and 1st Armoured Division.

The battle

The main striking force of the Indian I Corps was the 1st Armoured Division, which was supported by the 14th Infantry and 6th Mountain divisions. Indian forces seized the border area on 7 September 1965. This was followed by a short engagement at Jassoran in which the Pakistanis suffered losses in the form of about 10 tanks, consequently ensuring complete Indian dominance over the Sialkot-Pasrur railway.[32]

Realizing the severe threat posed by the Indians in Sialkot, the Pakistanis rushed two regiments of the 6th Armoured Division from Chamb, Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir (located today in Pakistani-administered Azad Jammu and Kashmir) to the Sialkot sector to support the Pakistani 7th Infantry Division fighting there. These units, supported by an independent tank destroyer squadron, amounted to about 135 tanks; 24 M47 and M48 Pattons, about 15 M36B1s and the rest Shermans. The majority of the American Pattons belonged to the new 25th Cavalry under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Nisar Ahmed Khan, which was sent to Chawinda. Intense fighting around the village of Gadgor between the Indian 1st Armoured Division and the Pakistani 25th Cavalry Regiment resulted in the Indian advance being stopped.

The Indian plan was to drive a wedge between Sialkot and the Pakistani 6th Armoured Division. At the time, only one Pakistani regiment was present in the area, and it was wiped out by the Indian 1st Armoured Division's thrust, spearheaded by the 43rd Lorried Infantry Brigade and a tank regiment attacking Gat. The bulk of the Indian 1st Armoured Brigade was hurled towards Phillora. Pakistani air attacks caused significant damage to the Indian tank columns and exacted a heavy toll on the truck columns and infantry. The terrain of the area was very different from that of the area surrounding Lahore, being quite dusty, and therefore the Indian offensive's advance was evident to the Pakistani 25th Cavalry by the rising dust columns on the Charwah-Phillora road.

Indian forces resumed their offensive on 10 September 1965 with multiple corps-sized assaults and succeeded in pushing the Pakistani forces back to their base at Chawinda, where the Indian advance was eventually stopped. A Pakistani counterattack at Phillora was repulsed with heavy losses, after which the Pakistanis took up defensive positions. The situation for the Pakistanis at this point was highly perilous; the Indians outnumbered them ten to one.

However, the Pakistani situation improved as reinforcements arrived, consisting of two independent brigades from Kashmir: the 8th Infantry Division, and more crucially, the 1st Armoured Division. For the next several days, Pakistani forces repulsed Indian attacks on Chawinda. A major Indian assault involving India's 1st Armoured and 6th Mountain divisions on 18 September was repelled, with the Indians suffering heavy losses. Following this, on 21 September, the Indians withdrew to a defensive position near their original bridgehead, with the retreat of India's advancing divisions, all the offensives were effectively halted on that front.[33]

Pakistani officers vetoed the proposed counterattack, dubbed "Operation Windup", in light of the Indians' retreat. According to the Pakistani commander-in-chief, the operation was cancelled due to the fact that "both sides had suffered heavy tank losses.… would have been of no strategic importance...." and, above all: "the decision... was politically motivated as by then the Government of Pakistan had made up their mind to accept [the] ceasefire and foreign-sponsored proposals".[10]

Outcome

The battle has widely been described as one of the largest tank battles since World War II.[34] On 22 September 1965, the United Nations Security Council unanimously passed a resolution that called for an immediate and unconditional ceasefire from both nations.[15][35] The war ended the following day. The international military and economic assistance to both countries had stopped when the war started. Pakistan had suffered attrition to its military might and serious reverses in the Battle of Asal Uttar and Chawinda, which made way for its acceptance of the United Nations ceasefire.[5]

Following the end of hostilities on 23 September 1965, India claimed to have held about 518 km2 (200 sq mi) of Pakistani territory in the Sialkot sector (although neutral analyses put the figure at around 460 km2 (180 sq mi) of territory), including the towns and villages of Phillora, Deoli, Bajragarhi, Suchetgarh, Pagowal, Chaprar, Muhadpur and Tilakpur. These were all returned to Pakistan after the signing of the Tashkent Declaration in January 1966.[36][37][2]

Published accounts

Documentaries

Battle of Chawinda − Indo Pak War 1965 − Lieutenant Colonel Ardeshir Tarapore (2018) is an Indian TV documentary which premiered on Veer by Discovery India.[38][39]

Notes

- ↑ "[Abrar Hussain] had fought in the World War II and won the MBE due to his bravery as a young army lieutenant. Later in the 1965 War, he was awarded the gallantry award, Hilal-i-Jurat, for leading an infantry brigade as part of the 6th Armoured Division that fought the famous tank battle with the Indian Army at Chawinda in Sialkot and halted the advance of the invading Indian troops in Pakistan’s territory."

- ↑ It is also called the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965.

- ↑ Pakistani military has long held a theory that the Indian objective was to cut the Grand Trunk Road at Wazirabad. The Grand Trunk Road is a major north–south highway that links, for example, Islamabad and Lahore.[19][20] Some western military analysts also reproduce this theory.[21]

- ↑ However, the history lists only 5 tank regiments in the composition: 4 Horse, 16 Cav, 17 Horse, 2 Lancers and 62 Cav.[25]

References

- ↑ Jogindar Singh (1993). Behind the Scene: An Analysis of India's Military Operations, 1947–1971. Lancer Publishers. pp. 217–219. ISBN 1-897829-20-5. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- 1 2 Chakravorty 1992a.

- ↑ Abrar Hussain (2005). Men of Steel: 6 Armored Division in the 1965 War. Army Education Publishing House. pp. 36–52. ISBN 969-8125-19-1.

- ↑ Nawaz 2008, pp. 227–230.

- 1 2 Krishna Rao 1991.

- ↑

Sources assessing stalemate:

- Manus I. Midlarsky (2011). Origins of Political Extremism: Mass Violence in the Twentieth Century and Beyond. Cambridge University Press. p. 256. ISBN 978-1139500777.: "Several major tank battles would be fought, one at Khem Karan in Punjab yielding a major Pakistani defeat, and another at Chawinda involving over 600 tanks, the outcome of which was inconclusive."

- Clodfelter, Micheal (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015 (4th ed.). McFarland. p. 600. ISBN 978-1476625850.: "Up to 600 tanks were engaged in the battle, primarily fought around Phillora and Chawinda, September 11–12, but the results were indecisive, largely because neither side properly supported their armor with infantry units."

- Hasan, Zubeida (Fourth Quarter 1965), "The India-Paktstan War – A summary account", Pakistan Horizon, 18 (4): 344–356, JSTOR 41393247: "After a few days of intense fighting, in which each side claimed to have inflicted heavy losses on the other, the war reached a stalemate on this front."

- ↑ Zaloga 1980, p. 19.

- ↑ Barua 2005, p. 191

- ↑ Philip, Snehesh Alex (12 August 2019). "How Pakistani Lt Col Nisar Ahmed won over Indian peers after stalling their advance in 1965". ThePrint. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- 1 2 3 Amin, Major A.H. "Battle of Chawinda Comedy of Higher Command Errors". Military historian. Defence journal(pakistan). Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- 1 2 Clodfelter, Micheal (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015 (4th ed.). McFarland. p. 600. ISBN 978-1476625850.

- 1 2 Chakravorty 1992a, p. 221.

- 1 2 Zaloga 1980, p. 35.

- ↑ Michael E. Haskew (2015). Tank: 100 Years of the World's Most Important Armored Military Vehicle. Voyageur Press. pp. 201–. ISBN 978-0-7603-4963-2.

- 1 2 Pradhan 2007.

- ↑ "Indo-Pakistan War of 1965". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ↑ Barua 2005, p. 190

- ↑ Singh 2013, Part 1, paragraphs 32–33.

- ↑ Bajwa 2013, pp. 254–255.

- ↑ Krishna Rao 1991, p. 129.

- ↑ Zaloga 1980, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Pradhan 2007, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Pradhan 2007, p. 50.

- ↑ Bajwa 2013, pp. 252–253.

- 1 2 Chakravorty 1992a, p. 194.

- ↑ Chakravorty 1992a, p. 223.

- 1 2 Bajwa 2013, pp. 253–254.

- ↑ Nawaz 2008, pp. 224, 225.

- ↑ Nawaz 2008, p. 224: "When news of the Indian attack came, he was told to move his troops to Pasrur on the night of 6/7 September as reserve for the 1 Corps. The move occurred during the night. Then at midnight, the division’s staff were told to return to their previous position around Gujranwala by 05:00 hours on 7 September! ... GHQ seemed to be making decisions quite arbitrarily."

- ↑ Higgins 2016, p. 46.

- ↑ Bajwa 2013, pp. 253–254. Bajwa does not list 11th Cavalry as being part of the 6th Armoured Division. But it is said to have came under its command from 8 September.

- ↑ Gupta, Hari Ram (1946). India-Pakistan war, 1965, Volume 1. Haryana Prakashan, 1967. pp. 181–182 – via archive.org.

- ↑ Barua 2005, p. 192.

- ↑ Bhattacharya, Brigadier Samir (2013). Nothing But! Book Three What Price Freedom. p. 490. ISBN 978-1482816259. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ↑ Midlarsky, Manus I. (2011). Origins of Political Extremism: Mass Violence in the Twentieth Century and Beyond (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 256. ISBN 978-0521700719.

- ↑ Chakravorty 1992b.

- ↑ Singh, Lt. Gen.Harbaksh (1991). War Despatches. New Delhi: Lancer International. p. 159. ISBN 81-7062-117-8.

- ↑ "Battle of Chawinda -Indo Pak War 1965 - Lieutenant Colonel Ardeshir Tarapore". Veer by Discovery. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ↑ "This R-Day, get ready for Discovery channel's 'Battle Ops'". The Hindu. 25 January 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

Bibliography

- Bajwa, Farooq (2013), From Kutch to Tashkent: The Indo-Pakistan War of 1965, Hurst Publishers, ISBN 978-1-84904-230-7

- Barua, Pradeep (2005), The State at War in South Asia, U of Nebraska Press, p. 190, ISBN 0-8032-1344-1

- Chakravorty, B. C. (1992a), "Operations in Sialkot sector" (PDF), History of the Indo-Pak War, 1965, Government of India, Ministry of Defence, History Division, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2011

- Chakravorty, B. C. (1992b), "War diplomacy, ceasefire, Tashkent" (PDF), History of the Indo-Pak War, 1965, Government of India, Ministry of Defence, History Division, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2011

- Higgins, David R. (2016), M48 Patton vs Centurion: Indo-Pakistani War 1965, Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4728-1093-9

- Kalyanaraman, S. (2015), "The sources of military change in India: An analysis of evolving strategies and doctrines towards Pakistan", in Jo Inge Bekkevold; Ian Bowers; Michael Raska (eds.), Security, Strategy and Military Change in the 21st Century: Cross-Regional Perspectives, Routledge, pp. 89–114, ISBN 978-1-317-56534-5

- Krishna Rao, K. V. (1991), Prepare or Perish: A Study of National Security, Lancer Publishers, ISBN 978-81-7212-001-6

- Nawaz, Shuja (2008), Crossed Swords: Pakistan, Its Army, and the Wars Within, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-547660-6

- Pradhan, R. D. (2007), 1965 War, the Inside Story: Defence Minister Y.B. Chavan's Diary of India-Pakistan War, Atlantic Publishers & Dist, ISBN 978-81-269-0762-5

- Singh, Lt Gen Harbakhsh (2013), War Despatches: Indo–Pak Conflict 1965, Lancer Publishers LLC, ISBN 978-1-935501-59-6

- Zaloga, Steven J. (1980), The M47 & M48 Patton Tanks, London: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 0-85045-466-2

Further reading

- Fricker, John (1979). Battle for Pakistan: the air war of 1965. I. Allan. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-71-100929-5.

External links

- Battle of Chawinda – Comedy of Higher Command Errors

- In Memory of Martyrs (first-hand account of the battle)