Order theory is a branch of mathematics that investigates the intuitive notion of order using binary relations. It provides a formal framework for describing statements such as "this is less than that" or "this precedes that". This article introduces the field and provides basic definitions. A list of order-theoretic terms can be found in the order theory glossary.

Background and motivation

Orders are everywhere in mathematics and related fields like computer science. The first order often discussed in primary school is the standard order on the natural numbers e.g. "2 is less than 3", "10 is greater than 5", or "Does Tom have fewer cookies than Sally?". This intuitive concept can be extended to orders on other sets of numbers, such as the integers and the reals. The idea of being greater than or less than another number is one of the basic intuitions of number systems (compare with numeral systems) in general (although one usually is also interested in the actual difference of two numbers, which is not given by the order). Other familiar examples of orderings are the alphabetical order of words in a dictionary and the genealogical property of lineal descent within a group of people.

The notion of order is very general, extending beyond contexts that have an immediate, intuitive feel of sequence or relative quantity. In other contexts orders may capture notions of containment or specialization. Abstractly, this type of order amounts to the subset relation, e.g., "Pediatricians are physicians," and "Circles are merely special-case ellipses."

Some orders, like "less-than" on the natural numbers and alphabetical order on words, have a special property: each element can be compared to any other element, i.e. it is smaller (earlier) than, larger (later) than, or identical to. However, many other orders do not. Consider for example the subset order on a collection of sets: though the set of birds and the set of dogs are both subsets of the set of animals, neither the birds nor the dogs constitutes a subset of the other. Those orders like the "subset-of" relation for which there exist incomparable elements are called partial orders; orders for which every pair of elements is comparable are total orders.

Order theory captures the intuition of orders that arises from such examples in a general setting. This is achieved by specifying properties that a relation ≤ must have to be a mathematical order. This more abstract approach makes much sense, because one can derive numerous theorems in the general setting, without focusing on the details of any particular order. These insights can then be readily transferred to many less abstract applications.

Driven by the wide practical usage of orders, numerous special kinds of ordered sets have been defined, some of which have grown into mathematical fields of their own. In addition, order theory does not restrict itself to the various classes of ordering relations, but also considers appropriate functions between them. A simple example of an order theoretic property for functions comes from analysis where monotone functions are frequently found.

Basic definitions

This section introduces ordered sets by building upon the concepts of set theory, arithmetic, and binary relations.

Partially ordered sets

Orders are special binary relations. Suppose that P is a set and that ≤ is a relation on P ('relation on a set' is taken to mean 'relation amongst its inhabitants'). Then ≤ is a partial order if it is reflexive, antisymmetric, and transitive, that is, if for all a, b and c in P, we have that:

- a ≤ a (reflexivity)

- if a ≤ b and b ≤ a then a = b (antisymmetry)

- if a ≤ b and b ≤ c then a ≤ c (transitivity).

A set with a partial order on it is called a partially ordered set, poset, or just ordered set if the intended meaning is clear. By checking these properties, one immediately sees that the well-known orders on natural numbers, integers, rational numbers and reals are all orders in the above sense. However, these examples have the additional property that any two elements are comparable, that is, for all a and b in P, we have that:

- a ≤ b or b ≤ a.

A partial order with this property is called a total order. These orders can also be called linear orders or chains. While many familiar orders are linear, the subset order on sets provides an example where this is not the case. Another example is given by the divisibility (or "is-a-factor-of") relation |. For two natural numbers n and m, we write n|m if n divides m without remainder. One easily sees that this yields a partial order. The identity relation = on any set is also a partial order in which every two distinct elements are incomparable. It is also the only relation that is both a partial order and an equivalence relation. Many advanced properties of posets are interesting mainly for non-linear orders.

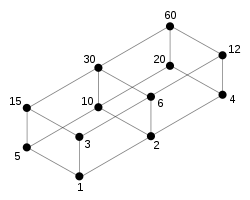

Visualizing a poset

Hasse diagrams can visually represent the elements and relations of a partial ordering. These are graph drawings where the vertices are the elements of the poset and the ordering relation is indicated by both the edges and the relative positioning of the vertices. Orders are drawn bottom-up: if an element x is smaller than (precedes) y then there exists a path from x to y that is directed upwards. It is often necessary for the edges connecting elements to cross each other, but elements must never be located within an edge. An instructive exercise is to draw the Hasse diagram for the set of natural numbers that are smaller than or equal to 13, ordered by | (the divides relation).

Even some infinite sets can be diagrammed by superimposing an ellipsis (...) on a finite sub-order. This works well for the natural numbers, but it fails for the reals, where there is no immediate successor above 0; however, quite often one can obtain an intuition related to diagrams of a similar kind.

Special elements within an order

In a partially ordered set there may be some elements that play a special role. The most basic example is given by the least element of a poset. For example, 1 is the least element of the positive integers and the empty set is the least set under the subset order. Formally, an element m is a least element if:

- m ≤ a, for all elements a of the order.

The notation 0 is frequently found for the least element, even when no numbers are concerned. However, in orders on sets of numbers, this notation might be inappropriate or ambiguous, since the number 0 is not always least. An example is given by the above divisibility order |, where 1 is the least element since it divides all other numbers. In contrast, 0 is the number that is divided by all other numbers. Hence it is the greatest element of the order. Other frequent terms for the least and greatest elements is bottom and top or zero and unit.

Least and greatest elements may fail to exist, as the example of the real numbers shows. But if they exist, they are always unique. In contrast, consider the divisibility relation | on the set {2,3,4,5,6}. Although this set has neither top nor bottom, the elements 2, 3, and 5 have no elements below them, while 4, 5 and 6 have none above. Such elements are called minimal and maximal, respectively. Formally, an element m is minimal if:

- a ≤ m implies a = m, for all elements a of the order.

Exchanging ≤ with ≥ yields the definition of maximality. As the example shows, there can be many maximal elements and some elements may be both maximal and minimal (e.g. 5 above). However, if there is a least element, then it is the only minimal element of the order. Again, in infinite posets maximal elements do not always exist - the set of all finite subsets of a given infinite set, ordered by subset inclusion, provides one of many counterexamples. An important tool to ensure the existence of maximal elements under certain conditions is Zorn's Lemma.

Subsets of partially ordered sets inherit the order. We already applied this by considering the subset {2,3,4,5,6} of the natural numbers with the induced divisibility ordering. Now there are also elements of a poset that are special with respect to some subset of the order. This leads to the definition of upper bounds. Given a subset S of some poset P, an upper bound of S is an element b of P that is above all elements of S. Formally, this means that

- s ≤ b, for all s in S.

Lower bounds again are defined by inverting the order. For example, -5 is a lower bound of the natural numbers as a subset of the integers. Given a set of sets, an upper bound for these sets under the subset ordering is given by their union. In fact, this upper bound is quite special: it is the smallest set that contains all of the sets. Hence, we have found the least upper bound of a set of sets. This concept is also called supremum or join, and for a set S one writes sup(S) or for its least upper bound. Conversely, the greatest lower bound is known as infimum or meet and denoted inf(S) or . These concepts play an important role in many applications of order theory. For two elements x and y, one also writes and for sup({x,y}) and inf({x,y}), respectively.

For example, 1 is the infimum of the positive integers as a subset of integers.

For another example, consider again the relation | on natural numbers. The least upper bound of two numbers is the smallest number that is divided by both of them, i.e. the least common multiple of the numbers. Greatest lower bounds in turn are given by the greatest common divisor.

Duality

In the previous definitions, we often noted that a concept can be defined by just inverting the ordering in a former definition. This is the case for "least" and "greatest", for "minimal" and "maximal", for "upper bound" and "lower bound", and so on. This is a general situation in order theory: A given order can be inverted by just exchanging its direction, pictorially flipping the Hasse diagram top-down. This yields the so-called dual, inverse, or opposite order.

Every order theoretic definition has its dual: it is the notion one obtains by applying the definition to the inverse order. Since all concepts are symmetric, this operation preserves the theorems of partial orders. For a given mathematical result, one can just invert the order and replace all definitions by their duals and one obtains another valid theorem. This is important and useful, since one obtains two theorems for the price of one. Some more details and examples can be found in the article on duality in order theory.

Constructing new orders

There are many ways to construct orders out of given orders. The dual order is one example. Another important construction is the cartesian product of two partially ordered sets, taken together with the product order on pairs of elements. The ordering is defined by (a, x) ≤ (b, y) if (and only if) a ≤ b and x ≤ y. (Notice carefully that there are three distinct meanings for the relation symbol ≤ in this definition.) The disjoint union of two posets is another typical example of order construction, where the order is just the (disjoint) union of the original orders.

Every partial order ≤ gives rise to a so-called strict order <, by defining a < b if a ≤ b and not b ≤ a. This transformation can be inverted by setting a ≤ b if a < b or a = b. The two concepts are equivalent although in some circumstances one can be more convenient to work with than the other.

Functions between orders

It is reasonable to consider functions between partially ordered sets having certain additional properties that are related to the ordering relations of the two sets. The most fundamental condition that occurs in this context is monotonicity. A function f from a poset P to a poset Q is monotone, or order-preserving, if a ≤ b in P implies f(a) ≤ f(b) in Q (Noting that, strictly, the two relations here are different since they apply to different sets.). The converse of this implication leads to functions that are order-reflecting, i.e. functions f as above for which f(a) ≤ f(b) implies a ≤ b. On the other hand, a function may also be order-reversing or antitone, if a ≤ b implies f(a) ≥ f(b).

An order-embedding is a function f between orders that is both order-preserving and order-reflecting. Examples for these definitions are found easily. For instance, the function that maps a natural number to its successor is clearly monotone with respect to the natural order. Any function from a discrete order, i.e. from a set ordered by the identity order "=", is also monotone. Mapping each natural number to the corresponding real number gives an example for an order embedding. The set complement on a powerset is an example of an antitone function.

An important question is when two orders are "essentially equal", i.e. when they are the same up to renaming of elements. Order isomorphisms are functions that define such a renaming. An order-isomorphism is a monotone bijective function that has a monotone inverse. This is equivalent to being a surjective order-embedding. Hence, the image f(P) of an order-embedding is always isomorphic to P, which justifies the term "embedding".

A more elaborate type of functions is given by so-called Galois connections. Monotone Galois connections can be viewed as a generalization of order-isomorphisms, since they constitute of a pair of two functions in converse directions, which are "not quite" inverse to each other, but that still have close relationships.

Another special type of self-maps on a poset are closure operators, which are not only monotonic, but also idempotent, i.e. f(x) = f(f(x)), and extensive (or inflationary), i.e. x ≤ f(x). These have many applications in all kinds of "closures" that appear in mathematics.

Besides being compatible with the mere order relations, functions between posets may also behave well with respect to special elements and constructions. For example, when talking about posets with least element, it may seem reasonable to consider only monotonic functions that preserve this element, i.e. which map least elements to least elements. If binary infima ∧ exist, then a reasonable property might be to require that f(x ∧ y) = f(x) ∧ f(y), for all x and y. All of these properties, and indeed many more, may be compiled under the label of limit-preserving functions.

Finally, one can invert the view, switching from functions of orders to orders of functions. Indeed, the functions between two posets P and Q can be ordered via the pointwise order. For two functions f and g, we have f ≤ g if f(x) ≤ g(x) for all elements x of P. This occurs for example in domain theory, where function spaces play an important role.

Special types of orders

Many of the structures that are studied in order theory employ order relations with further properties. In fact, even some relations that are not partial orders are of special interest. Mainly the concept of a preorder has to be mentioned. A preorder is a relation that is reflexive and transitive, but not necessarily antisymmetric. Each preorder induces an equivalence relation between elements, where a is equivalent to b, if a ≤ b and b ≤ a. Preorders can be turned into orders by identifying all elements that are equivalent with respect to this relation.

Several types of orders can be defined from numerical data on the items of the order: a total order results from attaching distinct real numbers to each item and using the numerical comparisons to order the items; instead, if distinct items are allowed to have equal numerical scores, one obtains a strict weak ordering. Requiring two scores to be separated by a fixed threshold before they may be compared leads to the concept of a semiorder, while allowing the threshold to vary on a per-item basis produces an interval order.

An additional simple but useful property leads to so-called well-founded, for which all non-empty subsets have a minimal element. Generalizing well-orders from linear to partial orders, a set is well partially ordered if all its non-empty subsets have a finite number of minimal elements.

Many other types of orders arise when the existence of infima and suprema of certain sets is guaranteed. Focusing on this aspect, usually referred to as completeness of orders, one obtains:

- Bounded posets, i.e. posets with a least and greatest element (which are just the supremum and infimum of the empty subset),

- Lattices, in which every non-empty finite set has a supremum and infimum,

- Complete lattices, where every set has a supremum and infimum, and

- Directed complete partial orders (dcpos), that guarantee the existence of suprema of all directed subsets and that are studied in domain theory.

- Partial orders with complements, or poc sets,[1] are posets with a unique bottom element 0, as well as an order-reversing involution such that

However, one can go even further: if all finite non-empty infima exist, then ∧ can be viewed as a total binary operation in the sense of universal algebra. Hence, in a lattice, two operations ∧ and ∨ are available, and one can define new properties by giving identities, such as

- x ∧ (y ∨ z) = (x ∧ y) ∨ (x ∧ z), for all x, y, and z.

This condition is called distributivity and gives rise to distributive lattices. There are some other important distributivity laws which are discussed in the article on distributivity in order theory. Some additional order structures that are often specified via algebraic operations and defining identities are

which both introduce a new operation ~ called negation. Both structures play a role in mathematical logic and especially Boolean algebras have major applications in computer science. Finally, various structures in mathematics combine orders with even more algebraic operations, as in the case of quantales, that allow for the definition of an addition operation.

Many other important properties of posets exist. For example, a poset is locally finite if every closed interval [a, b] in it is finite. Locally finite posets give rise to incidence algebras which in turn can be used to define the Euler characteristic of finite bounded posets.

Subsets of ordered sets

In an ordered set, one can define many types of special subsets based on the given order. A simple example are upper sets; i.e. sets that contain all elements that are above them in the order. Formally, the upper closure of a set S in a poset P is given by the set {x in P | there is some y in S with y ≤ x}. A set that is equal to its upper closure is called an upper set. Lower sets are defined dually.

More complicated lower subsets are ideals, which have the additional property that each two of their elements have an upper bound within the ideal. Their duals are given by filters. A related concept is that of a directed subset, which like an ideal contains upper bounds of finite subsets, but does not have to be a lower set. Furthermore, it is often generalized to preordered sets.

A subset which is - as a sub-poset - linearly ordered, is called a chain. The opposite notion, the antichain, is a subset that contains no two comparable elements; i.e. that is a discrete order.

Related mathematical areas

Although most mathematical areas use orders in one or the other way, there are also a few theories that have relationships which go far beyond mere application. Together with their major points of contact with order theory, some of these are to be presented below.

Universal algebra

As already mentioned, the methods and formalisms of universal algebra are an important tool for many order theoretic considerations. Beside formalizing orders in terms of algebraic structures that satisfy certain identities, one can also establish other connections to algebra. An example is given by the correspondence between Boolean algebras and Boolean rings. Other issues are concerned with the existence of free constructions, such as free lattices based on a given set of generators. Furthermore, closure operators are important in the study of universal algebra.

Topology

In topology, orders play a very prominent role. In fact, the collection of open sets provides a classical example of a complete lattice, more precisely a complete Heyting algebra (or "frame" or "locale"). Filters and nets are notions closely related to order theory and the closure operator of sets can be used to define a topology. Beyond these relations, topology can be looked at solely in terms of the open set lattices, which leads to the study of pointless topology. Furthermore, a natural preorder of elements of the underlying set of a topology is given by the so-called specialization order, that is actually a partial order if the topology is T0.

Conversely, in order theory, one often makes use of topological results. There are various ways to define subsets of an order which can be considered as open sets of a topology. Considering topologies on a poset (X, ≤) that in turn induce ≤ as their specialization order, the finest such topology is the Alexandrov topology, given by taking all upper sets as opens. Conversely, the coarsest topology that induces the specialization order is the upper topology, having the complements of principal ideals (i.e. sets of the form {y in X | y ≤ x} for some x) as a subbase. Additionally, a topology with specialization order ≤ may be order consistent, meaning that their open sets are "inaccessible by directed suprema" (with respect to ≤). The finest order consistent topology is the Scott topology, which is coarser than the Alexandrov topology. A third important topology in this spirit is the Lawson topology. There are close connections between these topologies and the concepts of order theory. For example, a function preserves directed suprema if and only if it is continuous with respect to the Scott topology (for this reason this order theoretic property is also called Scott-continuity).

Category theory

The visualization of orders with Hasse diagrams has a straightforward generalization: instead of displaying lesser elements below greater ones, the direction of the order can also be depicted by giving directions to the edges of a graph. In this way, each order is seen to be equivalent to a directed acyclic graph, where the nodes are the elements of the poset and there is a directed path from a to b if and only if a ≤ b. Dropping the requirement of being acyclic, one can also obtain all preorders.

When equipped with all transitive edges, these graphs in turn are just special categories, where elements are objects and each set of morphisms between two elements is at most singleton. Functions between orders become functors between categories. Many ideas of order theory are just concepts of category theory in small. For example, an infimum is just a categorical product. More generally, one can capture infima and suprema under the abstract notion of a categorical limit (or colimit, respectively). Another place where categorical ideas occur is the concept of a (monotone) Galois connection, which is just the same as a pair of adjoint functors.

But category theory also has its impact on order theory on a larger scale. Classes of posets with appropriate functions as discussed above form interesting categories. Often one can also state constructions of orders, like the product order, in terms of categories. Further insights result when categories of orders are found categorically equivalent to other categories, for example of topological spaces. This line of research leads to various representation theorems, often collected under the label of Stone duality.

History

As explained before, orders are ubiquitous in mathematics. However, the earliest explicit mentionings of partial orders are probably to be found not before the 19th century. In this context the works of George Boole are of great importance. Moreover, works of Charles Sanders Peirce, Richard Dedekind, and Ernst Schröder also consider concepts of order theory.

Contributors to ordered geometry were listed in a 1961 textbook:

It was Pasch in 1882, who first pointed out that a geometry of order could be developed without reference to measurement. His system of axioms was gradually improved by Peano (1889), Hilbert (1899), and Veblen (1904).

— H. S. M. Coxeter, Introduction to Geometry

In 1901 Bertrand Russell wrote "On the notion of order"[2] exploring the foundations of the idea through generation of series. He returned to the topic in part IV of The Principles of Mathematics (1903). Russell noted that binary relation aRb has a sense proceeding from a to b with the converse relation having an opposite sense, and sense "is the source of order and series". (p 95) He acknowledges Immanuel Kant[3] was "aware of the difference between logical opposition and the opposition of positive and negative". He wrote that Kant deserves credit as he "first called attention to the logical importance of asymmetric relations."

The term poset as an abbreviation for partially ordered set is attributed to Garrett Birkhoff in the second edition of his influential book Lattice Theory.[4][5]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Roller, Martin A. (1998), Poc sets, median algebras and group actions. An extended study of Dunwoody's construction and Sageev's theorem (PDF), Southampton Preprint Archive, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04, retrieved 2015-01-18

- ↑ Bertrand Russell (1901) Mind 10(2)

- ↑ Immanuel Kant (1763) Versuch den Begriff der negativen Grosse in die Weltweisheit einzufuhren

- ↑ Birkhoff 1940, p. 1.

- ↑ "Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics (P)". jeff560.tripod.com.

References

- Birkhoff, Garrett (1940). Lattice Theory. Vol. 25 (3rd Revised ed.). American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0-8218-1025-5.

- Burris, S. N.; Sankappanavar, H. P. (1981). A Course in Universal Algebra. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-90578-5.

- Davey, B. A.; Priestley, H. A. (2002). Introduction to Lattices and Order (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-78451-4.

- Gierz, G.; Hofmann, K. H.; Keimel, K.; Mislove, M.; Scott, D. S. (2003). Continuous Lattices and Domains. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications. Vol. 93. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80338-0.

External links

- Orders at ProvenMath partial order, linear order, well order, initial segment; formal definitions and proofs within the axioms of set theory.

- Nagel, Felix (2013). Set Theory and Topology. An Introduction to the Foundations of Analysis