In music, ornaments or embellishments are musical flourishes—typically, added notes—that are not essential to carry the overall line of the melody (or harmony), but serve instead to decorate or "ornament" that line (or harmony), provide added interest and variety, and give the performer the opportunity to add expressiveness to a song or piece. Many ornaments are performed as "fast notes" around a central, main note.

There are many types of ornaments, ranging from the addition of a single, short grace note before a main note to the performance of a virtuosic and flamboyant trill. The amount of ornamentation in a piece of music can vary from quite extensive (it was often extensive in the Baroque period, from 1600 to 1750) to relatively little or even none. The word agrément is used specifically to indicate the French Baroque style of ornamentation.

Improvised vs. written

In the Baroque period, it was common for performers to improvise ornamentation on a given melodic line. A singer performing a da capo aria,[1] for instance, would sing the melody relatively unornamented the first time and decorate it with additional flourishes and trills the second time. Similarly, a harpsichord player performing a simple melodic line was expected to be able to improvise harmonically and stylistically appropriate trills, mordents (upper or lower) and appoggiaturas.

Ornamentation may also be indicated by the composer. A number of standard ornaments (described below) are indicated with standard symbols in music notation, while other ornamentations may be appended to the score in small notes, or simply written out normally as fully sized notes. Frequently, a composer will have his or her own vocabulary of ornaments, which will be explained in a preface, much like a code. A grace note is a note written in smaller type, with or without a slash through it, to indicate that its note value does not count as part of the total time value of the bar. Alternatively, the term may refer more generally to any of the small notes used to mark some other ornament (see § Appoggiatura below), or in association with some other ornament's indication (see § Trill below), regardless of the timing used in the execution.

In Spain, melodies ornamented upon repetition ("divisions") were called "diferencias", and can be traced back to 1538, when Luis de Narváez published the first collection of such music for the vihuela.[2]

Types

Trill

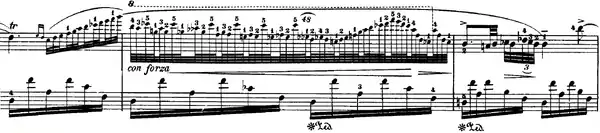

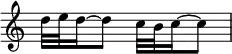

A trill, also known as a "shake", is a rapid alternation between an indicated note and the one above it. In simple music, trills may be diatonic, using just the notes of the scale; in other cases, the trill may be chromatic. The trill is usually indicated by either a tr or a tr~~, with the ~ representing the length of the trill, above the staff.

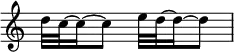

At a moderate tempo, the above might be executed as follows:

![{

\override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f

\relative c'' {

\time 2/4

g32[ a g \set stemRightBeamCount = #1 a \set stemLeftBeamCount = #1 g a g a]

g32[ a g \set stemRightBeamCount = #1 a \set stemLeftBeamCount = #1 g a g a]

}

}](../I/2e3ca08d09a909d41f9744b216b6c986.png.webp)

In Baroque music, the trill is sometimes indicated with a + (plus) sign above or below the note.

In the late 18th century, when performers played a trill, it always started from the upper note. However, "[Heinrich Christoph] Koch expressed no preference and observed that it was scarcely a matter of much importance whether the trill began one way or the other, since there was no audible difference after the initial note had been sounded."[3] Clive Brown writes that "Despite three different ways of showing the trills, it seems likely that a trill beginning with the upper note and ending with a turn was envisaged in each case."[4]

Sometimes it is expected that the trill will end with a turn (by sounding the note below rather than the note above the principal note, immediately before the last sounding of the principal note), or some other variation. Such variations are often marked with a few grace notes following the note that bears the trill indication.

There is also a single tone trill variously called trillo or tremolo in late Renaissance and early Baroque. Trilling on a single note is particularly idiomatic for the bowed strings.

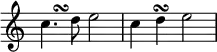

Mordent

A mordent is a rapid alternation between an indicated note, the note above (called the upper mordent, pralltriller, or simply mordent) or below (called the inverted mordent or lower mordent), and the indicated note again. The upper mordent is indicated by a short thick tilde (which may also indicate a trill); the lower mordent is the same with a short vertical line through it.

As with the trill, the exact speed with which a mordent is performed will vary according to the tempo of the piece, but, at a moderate tempo, the above might be executed as follows:

Confusion over the meaning of the unadorned word mordent has led to the modern terms upper and lower mordent being used, rather than mordent and inverted mordent. Practice, notation, and nomenclature vary widely for all of these ornaments; that is to say, whether, by including the symbol for a mordent in a musical score, a composer intended the direction of the additional note (or notes) to be played above or below the principal note written on the sheet music varies according to when the piece was written, and in which country.

In the Baroque period, a mordant (the German or Scottish equivalent of mordent) was what later came to be called an inverted mordent and what is now often called a lower mordent. In the 19th century, however, the name mordent was generally applied to what is now called the upper mordent. Although mordents are now thought of as a single alternation between notes, in the Baroque period a mordant may have sometimes been executed with more than one alternation between the indicated note and the note below, making it a sort of inverted trill. Mordents of all sorts might typically, in some periods, begin with an extra inessential note (the lesser, added note), rather than with the principal note as shown in the examples here. The same applies to trills, which in the Baroque and Classical periods would begin with the added, upper note. A lower inessential note may or may not be chromatically raised (that is, with a natural, a sharp, or even a double sharp) to make it one semitone lower than the principal note.

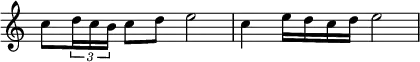

Turn

A turn is a short figure consisting of the note above the one indicated, the note itself, the note below the one indicated, and the note itself again. It is marked by a backwards S-shape lying on its side, sometimes known as an "inverted lazy S", above the staff. The details of its execution depend partly on the exact placement of the turn mark. For instance, the turns below

may be executed as

The exact speed with which a turn is executed can vary, as can its rhythm. The question of how a turn is best executed is largely one of context, convention, and taste. The lower and upper added notes may or may not be chromatically raised.

An inverted turn (the note below the one indicated, the note itself, the note above it, and the note itself again) is usually indicated by putting a short vertical line through the normal turn sign, though sometimes the sign itself is turned upside down.

Appoggiatura

An appoggiatura (/əˌpɒdʒəˈtjʊərə/; Italian: [appoddʒaˈtuːra]) is an added note that is important melodically (unlike an acciaccatura) and suspends the principal note by a portion of its time-value, often about half, but this may be considerably more or less depending on the context. The added note (the auxiliary note) is one degree higher or lower than the principal note, and may or may not be chromatically altered. Appoggiaturas are also usually on the strong or strongest beat of the resolution, are themselves emphasised, and are approached by a leap and left by a step in the opposite direction of the leap.[5][6]

An appoggiatura is often written as a grace note prefixed to a principal note and printed in small character,[7] without the oblique stroke:

This may be executed as follows:

Acciaccatura

The word acciaccatura (UK: /əˌtʃækəˈtjʊərə/, US: /-tʃɑːkə-/; Italian: [attʃakkaˈtuːra]) comes from the Italian verb acciaccare, "to crush". In the 18th century, it was an ornament applied to any of the main notes of arpeggiated chords, either a tone or semitone below the chord tone, struck simultaneously with it and then immediately released. Hence the German translation Zusammenschlag (together-stroke).[8]

In the 19th century, the acciaccatura (sometimes called short appoggiatura) came to be a shorter variant of the long appoggiatura, where the delay of the principal note is quick. It is written using a grace note (often a quaver, or eighth note), with an oblique stroke through the stem. In the Classical period, an acciaccatura is usually performed before the beat and the emphasis is on the main note, not the grace note. The appoggiatura long or short has the emphasis on the grace note.

The exact interpretation of this will vary according to the tempo of the piece, but the following is possible:

Whether the note should be played before or on the beat is largely a question of taste and performance practice. Exceptionally, the acciaccatura may be notated in the bar preceding the note to which it is attached, showing that it is to be played before the beat.[9] The implication also varies with the composer and the period. For example, Mozart's and Haydn's long appoggiaturas are – to the eye – indistinguishable from Mussorgsky's and Prokofiev's before-the-beat acciaccaturas.

Glissando

A glissando is a slide from one note to another, signified by a wavy line connecting the two notes.

All of the intervening diatonic or chromatic notes (depending on instrument and context) are heard, albeit very briefly. In this way, the glissando differs from portamento. In contemporary classical music (especially in avant garde pieces), a glissando tends to assume the whole value of the initial note.

Slide

A slide (or Schleifer in German) instructs the performer to begin one or two diatonic steps below the marked note and slide upward. The schleifer usually includes a prall trill or mordent trill at the end. Willard A. Palmer writes that "[t]he schleifer is a 'sliding' ornament,[1] usually used to fill in the gap between a note and the previous one."[10]

Nachschlag

The word Nachschlag (German: [ˈnaːxˌʃlaːk]) translates, literally, to “after-beat”, and refers to "the two notes that sometimes terminate a trill, and which, when taken in combination with the last two notes of the shake, may form a turn." The term Nachschlag may also refer to “an ornament that took the form of a supplementary note that, when placed after a main note, “steals” time from it.”[11]

The first definition of Nachschlag refers to the “shaken” or trilled version of the ornament, while the second definition refers to the “smooth” version. This ornament has also been referred to as a cadent or a springer in English Baroque performance practice. Instruction books from the Baroque period, such as Christopher Simpson's The Division Violist, refer to the cadent as an ornament in which "a Note is sometimes graced by joyning [sic] part of its sound to the note following... whose following Quaver is Placed with the ensuing Note, but played with the same Bow."[12]

In Western classical music

Renaissance and early Baroque music

From Silvestro Ganassi's treatise in 1535 we have instructions and examples of how musicians of the Renaissance and early Baroque periods decorated their music with improvised ornaments. Michael Praetorius spoke warmly of musicians' "sundry good and merry pranks with little runs/leaps".

Until the last decade of the 16th century the emphasis is on divisions, also known as diminutions, passaggi (in Italian), gorgia ("throat", first used as a term for vocal ornamentation by Nicola Vicentino in 1555), or glosas (by Ortiz, in both Spanish and Italian) – a way to decorate a simple cadence or interval with extra shorter notes. These start as simple passing notes, progress to step-wise additions and in the most complicated cases are rapid passages of equal valued notes – virtuosic flourishes. There are rules for designing them, to make sure that the original structure of the music is left intact. Towards the end of this period the divisions detailed in the treatises contain more dotted and other uneven rhythms and leaps of more than one step at a time.

Starting with Antonio Archilei (1589), the treatises bring in a new set of expressive devices called graces alongside the divisions. These have a lot more rhythmic interest and are filled with affect as composers took much more interest in text portrayal. It starts with the trillo and cascate, and by the time we reach Francesco Rognoni (1620) we are also told about fashionable ornaments: portar la voce, accento, tremolo, gruppo, esclamatione and intonatio.[13]

Key treatises detailing ornamentation:

- Silvestro Ganassi dal Fontego Opera intitulata Fontegara ..., Venice 1535

- Adrianus Petit Coclico Compendium musices Nuremberg, 1552

- Diego Ortiz Tratado de glosas sobre clausulas ..., Rome, 1553

- Juan Bermudo El libro llamado declaracion de instrumentos musicales, Ossuna, 1555

- Hermann Finck Pratica musica, Wittenberg, 1556

- Tomás de Santa María Libro llamado arte de tañer fantasia, 1565

- Girolamo Dalla Casa Il vero modo diminuir..., Venice, 1584

- Giovanni Bassano Ricercate, passaggi et cadentie ..., Venice 1585

- Giovanni Bassano Motetti, madrigali et canzoni francesi ... diminuiti, Venice 1591

- Riccardo Rognoni Passaggi per potersi essercitare nel diminuire, Venice 1592

- Lodovico Zacconi Prattica di musica, Venice, 1592

- Giovanni Luca Conforti Breve et facile maniera ... a far passaggi, Rome 1593

- Girolamo Diruta Il transylvano, 1593

- Giovanni Battista Bovicelli Regole, passaggi di musica, madrigali e motetti passaggiati, Venice 1594

- Aurelio Virgiliano Il Dolcimelo, MS, c.1600

- Giulio Caccini Le nuove musiche, 1602

- Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger, Libro primo di mottetti passeggiati à una voce, Rome, 1612

- Francesco Rognoni Selva de varii passaggi..., 1620

- Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger, Libro secondo d'arie à una e piu voci, Rome, 1623

- Giovanni Battista Spadi da Faenza Libro de passaggi ascendenti e descendenti, Venice, 1624

- Johann Andreas Herbst Musica practica, 1642

Baroque music

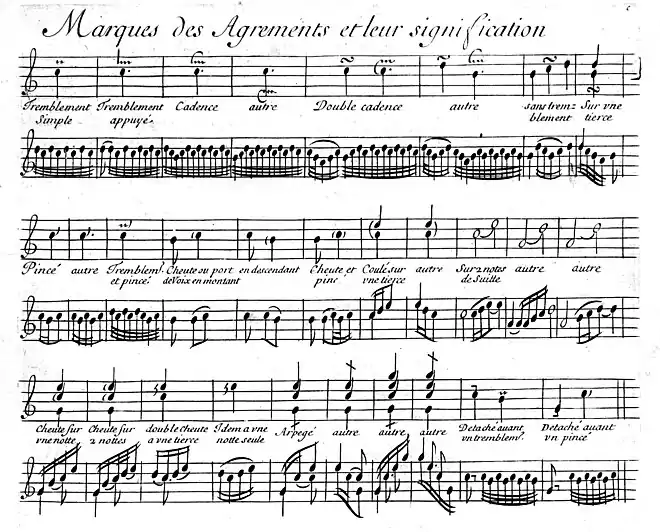

Ornaments in Baroque music take on a different meaning. Most ornaments occur on the beat, and use diatonic intervals more exclusively than ornaments in later periods do. While any table of ornaments must give a strict presentation, consideration has to be given to the tempo and note length, since at rapid tempos it would be difficult or impossible to play all of the notes that are usually required. One realisation of some common Baroque ornaments is set in the following table from the Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach by J.S. Bach:

Another realisation can be seen in the table in Pièces de clavecin (1689) by Jean-Henri d'Anglebert:

Classical period

In the late 18th and early 19th century, there were no standard ways of performing ornaments and sometimes several distinct ornaments might be performed in a same way.[14]

In the 19th century, performers were adding or improvising ornaments on compositions. As C.P.E Bach observed, "pieces in which all ornaments are indicated need give no trouble; on the other hand, pieces in which little or nothing is marked must be supplied with ornaments in the usual way."[15] Clive Brown explains that "For many connoisseurs of that period the individuality of a performer's embellishment of the divine notation was a vital part of the musical experience."

In Beethoven's work, however, there should not be any additional ornament added from a performer. Even in Mozart's compositions, ornaments not included in the score are not allowed, as Brown explains: "Most of the chamber music from Mozart onwards that still remains in the repertoire belongs to the kind in which every note is thought out and which tolerates virtually no ornamental additions of the type under consideration here..."[16] Recent scholarship has however brought this statement in question.[17]

In other music

Jazz

Jazz music incorporates a wide variety of ornaments including many of the classical ones mentioned above as well as a number of their own. Most of these ornaments are added either by performers during their solo extemporizations or as written ornaments. While these ornaments have universal names, their realizations and effects vary depending on the instrument. Jazz music incorporates most of the standard "classical" ornaments, such as trills, grace notes, mordents, glissandi and turns but adds a variety of additional ornaments such as "dead" or ghost notes (a percussive sound, notated by an "X"), "doit" notes and "fall" notes (annotated by curved lines above the note, indicating by direction of curve that the note should either rapidly rise or fall on the scale),[18] squeezes (notated by a curved line from an "X" to a specific pitch, that denotes an un-pitched glissando), and shakes (notated by a squiggly line over a note, which indicates a fast lip trill for brass players and a minor third trill for winds).[19]

Indian classical music

In Carnatic music, the Sanskrit term gamaka (which means "to move") is used to denote ornamentation. One of the most unusual forms of ornamentation in world music is the Carnatic kampitam which is about oscillating a note in diverse ways by varying amplitude, speed or number of times the note is oscillated. This is a highly subtle, yet scientific ornamentation as the same note can be oscillated in different ways based on the raga or context within a raga. For instance, the fourth note (Ma) in Shankarabharanam or Begada allows at least three to five types of oscillation based on the phrasings within the raga.

Another important gamaka in Carnatic is the "Sphuritam" which is about rendering a note twice but forcefully from a grace note immediately below it the second time. For instance, the third note (Ga) would be rendered plain first time and with a force from the second (Ri) the next time.

Celtic music

Ornamentation is a major distinguishing characteristic of Welsh, Irish, Scottish, and Cape Breton music. A singer, fiddler, flautist, harpist, tin whistler, piper or a player of another instrument may add grace notes (known as 'cuts' / 'strikes' in Irish fiddling), slides, rolls, cranns, doubling, mordents, drones, trebles (or birls in Scottish fiddling), or a variety of other ornaments to a given melody.[20]

See also

References

- 1 2 Westrup, Jack; McClymonds, Marita P.; Budden, Julian; Clements, Andrew; Carter, Tim; Walker, Thomas; Heartz, Daniel; Libby, Dennis (2001). "Aria". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.43315. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ↑ Elaine Sisman, "Variations, §4: Origins", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan, 2001).

- ↑ Brown 2004, p. 492.

- ↑ Brown 2004, p. 499.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-10-29. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Kent Kennan, Counterpoint, Fourth Edition, p. 40

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 225.

- ↑ Robert E. Seletsky, "Acciaccatura (It.; Fr. pincé étouffé; Ger. Zusammenschlag)", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan, 2001).

- ↑ Gould, Elaine (2011). Behind Bars - The definitive guide to music notation. Faber Music. p. 128. ISBN 9780571514564.

- ↑ First Lesson in Bach for the Piano, Edited by Walter Carroll & Willard A. Palmer, p. 3

- ↑ "Music Dictionary: N–Nh". Dolmetsch Online. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ↑ Dannreuther, Edward (1893). Musical Ornamentation. New York: Edwin F. Kalmus. pp. 65–67.

- ↑ Rognoni, Riccardo (2002). Passaggi per potersi essercitare nel diminuire (1592); edition with preface by Bruce Dickey. Arnaldo Forni Editore.

- ↑ Brown 2004, p. 456.

- ↑ Brown 2004, p. 455.

- ↑ Brown 2004, pp. 415–425.

- ↑ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Levin, Robert (29 October 2012), Improvising Mozart, lecture given at Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities

- ↑ Read, Gardner (1969). Music notation: a manual of modern practice. Allyn and Bacon. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ↑ Brye, John. "Interpretation of Jazz Band Literature" (PDF). The U.S. Army Field Band.

- ↑ Williams, Sean (2004). "Traditional Music: Ceol Tráidisiúnta: Melodic Ornamentation in the Connemara Sean-Nós Singing of Joe Heaney". New Hibernia Review / Iris Éireannach Nua. 8 (1): 122–145. ISSN 1092-3977. JSTOR 20557912.

Sources

- Brown, Clive (2004). Classical and Romantic Performing Practice 1750–1900. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195166655.

Further reading

- Donington, Robert. A Performer's Guide to Baroque Music. London: Faber & Faber, 1975.

- Neumann, Frederick. Ornamentation in Baroque and Post-Baroque Music, with Special Emphasis on J. S. Bach. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978. ISBN 0-691-09123-4 (cloth); ISBN 0-691-02707-2 (pbk).

External links

Media related to Ornaments (music) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ornaments (music) at Wikimedia Commons- Tovey, Donald Francis (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). pp. 912–915.