First edition cover | |

| Author | Aphra Behn |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | Early Modern English |

| Genre | Prose fiction |

| Publisher | Will. Canning |

Publication date | 1688 |

| Media type | |

| OCLC | 53261683 |

| 823.44 | |

| LC Class | PR3317 .O7 |

| Text | Oroonoko: or, the Royal Slave. A True History. at Wikisource |

Oroonoko: or, the Royal Slave is a work of prose fiction by Aphra Behn (1640–1689), published in 1688 by William Canning and reissued with two other fictions later that year. It was also adapted into a play. The eponymous hero is an African prince from Coramantien who is tricked into slavery and sold to European colonists in Surinam where he meets the narrator. Behn's text is a first-person account of Oroonoko's life, love, rebellion, and execution.[1]

Behn, often cited as the first known professional female writer,[2] was a successful playwright, poet, translator and essayist. She began writing prose fiction in the 1680s, probably in response to the consolidation of theatres that led to a reduced need for new plays.[3] Published less than a year before she died, Oroonoko is sometimes described as one of the first novels in English. Interest in Oroonoko has increased since the 1970s, with critics arguing that Behn is the foremother of British female writers, and that Oroonoko is a crucial text in the history of the novel.[4]

The novel's success was jump-started by a popular 1695 theatrical adaptation by Thomas Southerne which ran regularly on the British stage throughout the first half of the 18th century, and in America later in the century.

Plot Summary and Analysis

Plot Summary

Oroonoko: or, the Royal Slave is a relatively short novel set in a narrative frame. The narrator opens with an account of the colony of Surinam and its inhabitants. Within this is a historical tale concerning the Coramantien grandson of an African king, Prince Oroonoko. At a very young age Prince Oroonoko was trained for battle, becoming an expert captain by the age of seventeen. During a battle the best general sacrifices himself for the Prince by taking an arrow for him. In sight of this event, the Prince takes the place of General. Oroonoko decides to honorably visit the daughter of the deceased general to offer the "Trophies of her Father's Victories", but he immediately falls in love with Imoinda and later asks for her hand in marriage.

The king hears Imoinda described as the most beautiful and charming in the land, and he also falls in love. Despite his Intelligence saying she had been claimed by Oroonoko, the king gives Imoinda the royal veil, thus forcing her to become one of his wives, even though she is already promised to Oroonoko. Imoinda unwillingly, but dutifully, enters the king's harem (the Otan), and Oroonoko is comforted by his assumption that the king is too old to ravish her. Over time the Prince plans a tryst with the help of the sympathetic Onahal (one of the king's wives) and Aboan (a friend to the prince). The Prince and Imoinda are reunited for a short time and consummate their marriage, but they are eventually discovered. Imoinda and Onahal are punished for their actions by being sold as slaves. The king's guilt, however, leads him to lie to Oroonoko that Imoinda has instead been executed, since death was thought to be better than slavery. The Prince grieves. Later, after winning another tribal war, Oroonoko and his men visit a European slave trader on his ship and are tricked and shackled after drinking. The slave trader plans to sell the Prince and his men as slaves and carries them to Surinam in the West Indies. Oroonoko is purchased by a Cornish man named Trefry, but given special treatment due to his education and ability to speak French and English (which he learned from his own French mentor). Trefry mentions that he came to own a most beautiful enslaved woman and had to stop himself from raping her. Unbeknownst to Oroonoko, Trefry is speaking of Imoinda who is at the same plantation. The two lovers are reunited under the slave names of Caesar and Clemene.

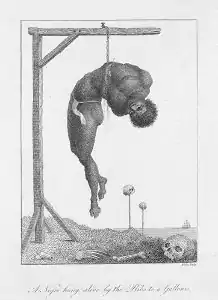

The narrator and Trefry continue to treat the hero as an honored guest. The narrator recounts various entertaining episodes, including reading, hunting, visiting native villages, and capturing an electric eel. Oroonoko and Imoinda live as husband and wife in their own slave cottage, and once she becomes pregnant, Oroonoko petitions for their return to the homeland. After being put off with vague promises of the governor's arrival, Oroonoko organizes a slave revolt. The slaves, including Imoinda, fight valiantly, but the majority surrender when deputy governor Byam promises them amnesty. After the surrender, Oroonoko and Tuscan, his second-in-command, are punished and whipped by their former allies at the command of Byam. To avenge his honor, Oroonoko vows to kill Byam. He worries, however, that to do so would make Imoinda vulnerable to reprisal after his death. The couple both decide that he should kill her, and so Imoinda dies by his hand. Oroonoko hides in the woods to mourn her and grows weaker, becoming unable to complete his revenge. When he is discovered, he decides to show his fearlessness in the face of death. Oroonoko cuts off a piece of his own throat, disembowels himself, and stabs the first man who tries to approach him. Once captured, he is bound to a post. Resigned to his death, Oroonoko asks for a pipe to smoke as Banister has him quartered and dismembered.

Analysis

The novel is written in a mixture of first and third person, as the narrator relates events in Africa secondhand, and herself witnesses, and participates in, the actions that take place in Surinam. The narrator is a lady who has come to Surinam with her unnamed father, a man intended to be the new lieutenant-general of the colony. He, however, dies on the voyage from illness. The narrator and her family are put up in the finest house in the settlement, in accord with their station, and the narrator's experiences of meeting the indigenous peoples and slaves are intermixed with the main plot of Oroonoko and Imoinda. At the conclusion of the narrative, the narrator leaves Surinam for London.

Structurally, there are three significant pieces to the narrative, which does not flow in a strictly biographical manner. The novel opens with a statement of veracity, wherein the narrator claims to be writing neither fiction nor pedantic history. She claims to be an eyewitness and to be writing without any embellishment or agenda, relying solely upon real events. A description of Surinam and the Southern American Indians follows. The narrator regards the indigenous peoples as innocent and living in a golden age. Next, she provides the history of Oroonoko in Africa: the betrayal by his grandfather, the captivity of Imoinda, and his capture by the slaver captain. The narrative then returns to Surinam and the present: Oroonoko and Imoinda are reunited, and Oroonoko and Imoinda meet the narrator and Trefry. The final section describes Oroonoko's rebellion and its aftermath.

Biographical and historical background

Oroonoko is now the most studied of Aphra Behn's novels, but it was not immediately successful in her own lifetime. It sold well, but the adaptation for the stage by Thomas Southerne (see below) made the story as popular as it became. Soon after her death, the novel began to be read again, and from that time onward the factual claims made by the novel's narrator, and the factuality of the whole plot of the novel, have been accepted and questioned with greater and lesser credulity. Because Mrs. Behn was not available to correct or confirm any information, early biographers assumed the first-person narrator was Aphra Behn speaking for herself and incorporated the novel's claims into their accounts of her life. It is important, however, to recognise that Oroonoko is a work of fiction and that its first-person narrator—the protagonist—need be no more factual than Jonathan Swift's first-person narrator, ostensibly Gulliver, in Gulliver's Travels, Daniel Defoe's shipwrecked narrator in Robinson Crusoe, or the first-person narrator of A Tale of a Tub.

Fact and fiction in the narrator

Researchers today cannot say whether or not the narrator of Oroonoko represents Aphra Behn and, if so, tells the truth. Scholars have argued for over a century about whether or not Behn even visited Suriname and, if so, when. On one hand, the narrator reports that she "saw" sheep in the colony, when the settlement had to import meat from Virginia, as sheep, in particular, could not survive there. Also, as Ernest Bernbaum argues in "Mrs. Behn's 'Oroonoko'", everything substantive in Oroonoko could have come from accounts by William Byam and George Warren that were circulating in London in the 1660s. However, as J.A. Ramsaran and Bernard Dhuiq catalogue, Behn provides a great deal of precise local colour and physical description of the colony. Topographical and cultural verisimilitude were not a criterion for readers of novels and plays in Behn's day any more than in Thomas Kyd's, and Behn generally did not bother with attempting to be accurate in her locations in other stories. Her plays have quite indistinct settings, and she rarely spends time with topographical description in her stories.[5] Secondly, all the Europeans mentioned in Oroonoko were really present in Surinam in the 1660s. It is interesting, if the entire account is fictional and based on reportage, that Behn takes no liberties of invention to create Europeans she might need. Finally, the characterisation of the real-life people in the novel does follow Behn's own politics. Behn was a lifelong and militant royalist, and her fictions are quite consistent in portraying virtuous royalists and put-upon nobles who are opposed by petty and evil republicans/Parliamentarians. Had Behn not known the individuals she fictionalized in Oroonoko, it is extremely unlikely that any of the real royalists would have become fictional villains or any of the real republicans fictional heroes, and yet Byam and James Bannister, both actual royalists in the Interregnum, are malicious, licentious, and sadistic, while George Marten, a Cromwellian republican, is reasonable, open-minded, and fair.[5]

On balance, it appears that Behn truly did travel to Surinam. The fictional narrator, however, cannot be the real Aphra Behn. For one thing, the narrator says that her father was set to become the deputy governor of the colony and died at sea en route. This did not happen to Bartholomew Johnson (Behn's father), although he did die between 1660 and 1664.[6] There is no indication at all of anyone except William Byam being Deputy Governor of the settlement, and the only major figure to die en route at sea was Francis, Lord Willoughby, the colonial patent holder for Barbados and "Suriname." Further, the narrator's father's death explains her antipathy toward Byam, for he is her father's usurper as Deputy Governor of Surinam. This fictionalised father thereby gives the narrator a motive for her unflattering portrait of Byam, a motive that might cover for the real Aphra Behn's motive in going to Surinam and for the real Behn's antipathy toward the real Byam.

It is also unlikely that Behn went to Surinam with her husband, although she may have met and married in Surinam or on the journey back to England. A socially creditable single woman in good standing would not have gone unaccompanied to Surinam. Therefore, it is most likely that Behn and her family went to the colony in the company of a lady. As for her purpose in going, Janet Todd presents a strong case for its being spying. At the time of the events of the novel, the deputy governor Byam had taken absolute control of the settlement and was being opposed not only by the formerly republican Colonel George Marten, but also by royalists within the settlement. Byam's abilities were suspect, and it is possible that either Lord Willoughby or Charles II would be interested in an investigation of the administration there.

Beyond these facts, there is little known. The earliest biographers of Aphra Behn not only accepted the novel's narrator's claims as true, but Charles Gildon even invented a romantic liaison between the author and the title character, while the anonymous Memoirs of Aphra Behn, Written by One of the Fair Sex (both 1698) insisted that the author was too young to be romantically available at the time of the novel's events. Later biographers have contended with these suggestions, either to deny or prove them.

Models for Oroonoko

One figure who matches aspects of Oroonoko is the John Allin, a settler in Surinam. Allin was disillusioned and miserable in Surinam, and he took to over-indulging in alcohol and wild, lavish blasphemies so shocking that Governor Byam believed that the repetition of them at Allin's trial cracked the foundation of the courthouse.[7] In the novel, Oroonoko plans to kill Byam and then himself, and this matches a plot that Allin had to kill Lord Willoughby and then commit suicide, for, he said, it was impossible to "possess my own life, when I cannot enjoy it with freedom and honour".[8] He wounded Willoughby and was taken to prison, where he killed himself with an overdose. His body was taken to a pillory,

where a Barbicue was erected; his Members cut off, and flung in his face, they had his Bowels burnt under the Barbicue... his Head to be cut off, and his Body to be quartered, and when dry-barbicued or dry roasted... his Head to be stuck on a pole at Parham (Willoughby's residence in Surinam), and his Quarters to be put up at the most eminent places of the Colony.[8]

While Behn was in Surinam (1663), she would have seen a slave ship arrive with 130 "freight", 54 having been "lost" in transit. Although the African slaves were not treated differently from the indentured servants coming from Europe (and were, in fact, more highly valued),[9] their cases were hopeless, and both slaves, indentured servants, and local inhabitants attacked the settlement. There was no single rebellion, however, that matched what is related in Oroonoko. Further, the character of Oroonoko is physically different from the other slaves by being blacker skinned, having a Roman nose, and having straight hair. The lack of historical record of a mass rebellion, the unlikeliness of the physical description of the character (when Europeans at the time had no clear idea of race or an inheritable set of "racial" characteristics), and the European courtliness of the character suggests that he is most likely invented wholesale. Additionally, the character's name is artificial. There are names in the Yoruba language that are similar, but the African slaves of Surinam were from Ghana.[9]

Instead of from life, the character seems to come from literature, for his name is reminiscent of Oroondates, a character in La Calprenède's Cassandra, which Behn had read.[9] Oroondates is a prince of Scythia whose desired bride is snatched away by an elder king. Previous to this, there is an Oroondates who is the satrap of Memphis in the Æthiopica, a novel from late antiquity by Heliodorus of Emesa. Many of the plot elements in Behn's novel are reminiscent of those in the Æthiopica and other Greek romances of the period. There is a particular similarity to the story of Juba in La Calprenède's romance Cléopâtre, who becomes a slave in Rome and is given a Roman name—Coriolanus—by his captors, as Oroonoko is given the Roman name of Caesar.[10]

Alternatively, it could be argued that "Oroonoko" is a homophone for the Orinoco River, along which the colony of Surinam was established and it is possible to see the character as an allegorical figure for the mismanaged territory itself. Oroonoko, and the crisis of values of aristocracy, slavery, and worth he represents to the colonists, is emblematic of the new world and colonisation itself: a person like Oroonoko is symptomatic of a place like the Orinoco.

The name "Oroonoko" is also associated with tobacco.[11]

Slavery and Behn's attitudes

According to biographer Janet Todd, Behn did not oppose slavery per se. She accepted the idea that powerful groups would enslave the powerless, and she would have grown up with Oriental tales of "The Turk" taking European slaves.[12] Although it has never been proven that Behn was actually married, the most likely candidate for her husband is Johan Behn, who sailed on The King David from the German imperial free city of Hamburg.[13] This Johan Behn was a slaver whose residence in London later was probably a result of acting as a mercantile cover for Dutch trade with the colony of Suriname under a false flag. One could argue that if Aphra Behn had been opposed to slavery as an institution, it is not very likely that she would have married a slave trader. At the same time, it is fairly clear that she was not happy in marriage, and Oroonoko, written twenty years after the death of her husband, has, among its cast of characters, no one more evil than the slave ship captain who tricks and captures Oroonoko.[14] It can also be argued that Behn's attitude towards slavery can be exemplified through her characteristics of Oroonoko and Imoinda, both characters given significantly positive attributes. Oroonoko was a strong, brave, heroic figure, while Imoinda was beautiful and pure in her ways.

The final words of the novel are a slight expiation of the narrator's guilt, but it is for the individual man she mourns and for the individual that she writes a tribute, and she lodges no protest over slavery itself. A natural king could not be enslaved, and, as in the play Behn wrote while in Surinam, The Young King, no land could prosper without a king.[14] Her fictional Surinam is a headless body. Without a true and natural leader (a king) the feeble and corrupt men of position abuse their power. What was missing was Lord Willoughby, or the narrator's father: a true lord. In the absence of such leadership, a true king, Oroonoko, is misjudged, mistreated, and killed.[14]

One potential motive for the novel, or at least one political inspiration, was Behn's view that Surinam was a fruitful and potentially wealthy settlement that needed only a true noble to lead it.[14] Like others sent to investigate the colony, she felt that Charles was not properly informed of the place's potential. When Charles gave up Surinam in 1667 with the Treaty of Breda, Behn was dismayed. This dismay is enacted in the novel in a graphic fashion: if the colony was mismanaged and the slaves mistreated by having an insufficiently noble ruler there, then the democratic and mercantile Dutch would be far worse. Accordingly, the passionate misrule of Byam is replaced by the efficient and immoral management of the Dutch. Charles had a strategy for a united North American presence, however, and his gaining of New Amsterdam for Surinam was part of that larger vision. Neither Charles II nor Aphra Behn could have known how correct Charles's bargain was, but Oroonoko can be seen as a royalist's demurral.[14]

Historical significance

Behn was a political writer of fiction and for the stage, and though not didactic in purpose, most of her works have distinct political content. The timing of Oroonoko's publication must be seen in its own context as well as in the larger literary tradition (see below). According to Charles Gildon, Aphra Behn wrote Oroonoko even with company present, and Behn's own account suggests that she wrote the novel in a single sitting, with her pen scarcely rising from the paper. If Behn travelled to Surinam in 1663–64, she felt no need for twenty-four years to write her "American story" and then felt a sudden and acute passion for telling it in 1688. It is therefore wise to consider what changes were in the air in that year that could account for the novel.

The year 1688 was a time of massive anxiety in Crown politics.[15] Charles II had died in February 1685, and James II came to the throne later in the same year. James's purported Roman Catholicism and his marriage to an avowedly Roman Catholic bride roused the old Parliamentarian forces to speak of rebellion again. This is the atmosphere for the writing of Oroonoko. One of the most notable features of the novel is that Oroonoko insists, over and over again, that a king's word is sacred, that a king must never betray his oaths, and that a measure of a person's worth is the keeping of vows. Given that men who had sworn fealty to James were now casting about for a way of getting a new king, this insistence on fidelity must have struck a chord. Additionally, the novel is fanatically anti-Dutch and anti-democratic, even if it does, as noted above, praise faithful former republicans like Trefry over faithless former royalists like Byam. In as much as the candidate preferred by the Whig Party for the throne was William of Orange, the novel's stern reminders of Dutch atrocities in Surinam and powerful insistence on the divine and emanate nature of royalty were likely designed to awaken Tory objections.

Behn's side would lose the contest, and the Glorious Revolution would end with the Act of Settlement 1701, whereby Protestantism would take precedence over sanguineous processes in the choice of monarch ever after. Indeed, so thoroughly did the Stuart cause fail that readers of Oroonoko may miss the topicality of the novel.[16]

Literary significance

Claims for Oroonoko's being the "first English novel" are difficult to sustain. In addition to the usual problems of defining the novel as a genre, Aphra Behn had written at least one epistolary novel prior to Oroonoko. The epistolary work Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister predates Oroonoko by more than five years. However, Oroonoko is one of the very early novels of the particular sort that possesses a linear plot and follows a biographical model. It is a mixture of theatrical drama, reportage, and biography that is easy to recognise as a novel.[16]

Oroonoko is the first European novel to show Africans in a sympathetic manner. At the same time, this novel is as much about the nature of kingship as it is about the nature of race. Oroonoko is a prince, and he is of noble lineage whether of African or European descent, and the novel's regicide is devastating to the colony. The theatrical nature of the plot follows from Behn's previous experience as a dramatist.[16] The language she uses in Oroonoko is far more straightforward than in her other novels, and she dispenses with a great deal of the emotional content of her earlier works. Further, the novel is unusual in Behn's fictions by having a very clear love story without complications of gender roles.[16]

Critical response to the novel has been coloured by the struggle over the debate over the slave trade and the struggle for female equality. In the 18th century, audiences for Southerne's theatrical adaptation and readers of the novel responded to the love triangle in the plot. Oroonoko on the stage was regarded as a great tragedy and a highly romantic and moving story, and on the page as well the tragic love between Oroonoko and Imoinda, and the menace of Byam, captivated audiences. As the European and American disquiet with slavery grew, Oroonoko was increasingly seen as protest to slavery. Wilbur L. Cross wrote, in 1899, that "Oroonoko is the first humanitarian novel in English." He credits Aphra Behn with having opposed slavery and mourns the fact that her novel was written too early to succeed in what he sees as its purpose (Moulton 408). Indeed, Behn was regarded explicitly as a precursor of Harriet Beecher Stowe. In the 20th century, Oroonoko has been viewed as an important marker in the development of the "noble savage" theme, a precursor of Rousseau and a furtherance of Montaigne, as well as a proto-feminist work.[17]

Recently (and sporadically in the 20th century) the novel has been seen in the context of 17th-century politics and 16th-century literature. Janet Todd argues that Behn deeply admired Othello, and identified elements of Othello in the novel. In Behn's longer career, her works center on questions of kingship quite frequently, and Behn herself took a radical philosophical position. Her works question the virtues of noble blood as they assert, repeatedly, the mystical strength of kingship and of great leaders. The character of Oroonoko solves Behn's questions by being a natural king and a natural leader, a man who is anointed and personally strong, and he is poised against nobles who have birth but no actual strength.

The New World setting

With Oroonoko, Aphra Behn took on the challenge of blending contemporary literary concerns, which were often separated by genre, into one cohesive work. Restoration literature had three common elements: the New World setting, courtly romance, and the concept of heroic tragedy. John Dryden, a prominent playwright in 1663, co-wrote The Indian Queen and wrote the sequel The Indian Emperour. Both plays have the three aspects of Restoration literature, and "Behn was certainly familiar with both plays",[18] influencing her writing as seen in the opening of the tale. Behn takes the Restoration themes and recreates them, bringing originality. One reason Behn may have changed the elements is because Oroonoko was written near the end of the Restoration period. Readers were aware of the theme, so Behn wanted to give them something fresh. Behn changed the New World setting, creating one that readers were unfamiliar with. Challenging her literary abilities even further, Behn recreates the Old World setting. Behn gives readers an exotic world, filling their heads with descriptive details. Behn was the first person to blend new elements with the old Restoration essentials. The New World was set in the contemporary Caribbean, not in Mexico as previous centuries were accustomed to. The New World gave readers knowledge of a foreign place, "a colony in America called Surinam, in the West Indies".[19] Behn paints a picture-perfect New World unspoiled by natives—one that contrasts with Dryden's previous work.[20] Behn's New World seems almost utopian as she describes how the people get along: "with these People, ... we live in perfect Tranquility, and good Understanding, as it behooves us to do."[21] This New World is unique during this period; it is "simultaneously a marvelous prelapsarian paradise and the thoroughly commercialised crossroads of international trade".[22] It seems hard to believe that in such a romantic setting Behn can blend heroic tragedy, yet she accomplishes this effect through the character of Oroonoko. The Old World changes as Behn recreates the trade route back across the Atlantic to Africa, instead of Europe, becoming "the first European author who attempted to render the life lived by sub-Saharan African characters on their own continent."[20] There were few accounts of coastal African kingdoms at that time. Oroonoko is truly an original play blending three important elements in completely original ways, with her vision of the New World constituting a strong example of the change.[20]

Although Behn assures that she is not looking to entertain her reader with the adventures of a feigned hero, she does exactly this to enhance and romanticize the stories of Oroonoko. Ramesh Mallipeddi had stressed that "spectacle was the main mediator" for the representation of foreign cultures in the Restoration era.[23] Therefore, Behn describes Oroonoko's native beauty as a spectacle of 'beauty so transcending' that surpassed 'all those of his gloomy race'.[24] She completely romanticizes Oroonoko's figure by portraying him as an ideal handsome hero; however due to the color of his skin, his body is still constricted within the limits of exoticism. Oroonoko has all the qualities of an aristocrat, but his ebony skin and country of origin prevent him from being a reputable European citizen.[16] Due to these foreign qualities, his Europeaness is incomplete. He has the European-like education and air, but lacks the skin color and legal status. Behn uses this conflicting description of Oroonoko to infuse some European familiarity into his figure while still remaining exotic enough. She compares Oroonoko to well-known historical figures like Hannibal and Alexander and describes Oroonoko's running, wrestling and killing of tigers and snakes. Albert J. Rivero states that this comparison to great Western conquerors and kings translates and naturalizes Oroonoko's foreignness into familiar European narratives.[16]

Character list

- Oroonoko – The protagonist of the story. Love interest of Imoinda. Oroonoko is the prince of Coramantien, who is sold into slavery in Surinam by European slave traders. Oroonoko later leads a slave revolt and is killed by his slave masters.

- Caesar – the English name that Oroonoko is given after he is sold into slavery. After Oroonoko’s purchase, he is exclusively referred to by this name for the remainder of the text.

- Imoinda – The love interest of Oroonoko. After Oroonoko takes her virginity, the King of Coramantien sells her into slavery. Imoinda and Oroonoko eventually end up on the same plantation, marry, and have children. Imoinda’s pregnancy is the impetus for their slave revolt, and she is eventually killed by Oroonoko.

- Clemene – The English name that Imoinda is given after she is sold into slavery. Imoinda is mostly referred to as Clemene after her purchase, but at the end of the text she is once again addressed as Imoinda.

- King of Coramantien – The elderly king and grandfather of Oroonoko. He hears rumors of Imoinda and takes her as a member of his harem. After Oroonoko takes Imoinda’s virginity, the king sells her into slavery and lies to Oroonoko, telling him that she was instead executed.

- Aboan – A friend of Oroonoko's from Coramantien. He helps Oroonoko visit Imoinda after she is forced into the king's harem.

- Onahal – An older women in the king's harem. She helps Oroonoko visit Imoinda after Imoinda is forced into the king's harem.

- Tuscan – A fellow slave to Oronokoo. He plays a vital role in the slave resistance against Governor Byam.

- Governor Byam – the governor of Surinam and the owner of the plantation that Oroonoko and Imoinda are living on. He is expected to free Oroonoko and Imoinda, but never arrives.

- Trefrey – the slave owner that eventually purchases both Oroonoko and Imoinda.

Themes

Kingship

Aphra Behn herself held incredibly strong pro-monarchy views that carried over into her writing of Oroonoko.[25] The idea that Behn attempts to present within the work is that the idea of royalty and natural kingship can exist even within a society of slaves. Although Oroonoko himself is a native who later becomes a slave, he possesses the traits of those typically required of a king within a typically civilized society.[26] He is admired and respected by those who follow him, and even in death he keeps his royal dignity intact—as he would rather be executed by his owners than surrender his self-respect. Oroonoko's death can be viewed as being unjustified and outrageous as the death of any king would be when caused by those who fall below him, as even though the whites are the ones who enslaved him, they are portrayed as being the ones who are the true animals.[25]

Female narrative

The unnamed female narrator of the story serves as being a strong reflection of a woman's role in society throughout the 18th century, as well as being a reflection of Behn's own personal views regarding the major themes within her work. Women within this time period were most often expected to remain silent and on the sidelines, simply observing rather than actively contributing, and the narrator in Oroonoko is a portrayal of that. A female narrator is also a way to voice the real world disagreements over women's rights, as well as slavery, to the fictional story. The narrator's disgust surrounding the treatment of Oroonoko, as well as her inability to watch his murder, is a way in which Behn inserts her own voice and viewpoints into the story, as her feelings towards kingship, slavery and the slave trade have been established. Likewise, the narrator's relatively inactive involvement in the story could also be viewed as a reflection of the way in which female writers of the time were viewed as well—silent and non contributing due to their male peers—especially with Behn herself being one of very few female authors of the time.[27]

Slavery and servitude

The view of slavery and other forms of forced servitude in Oroonoko is intentionally mixed. While Oroonoko himself is shown as wrongly imprisoned by the whims and cruelty of his European captors, the character himself comes out in direct support of slavery multiple times throughout the text. Slavery is depicted as a natural order of things, the weak overcoming the strong and using these lower people as tools in order to conduct busywork such as manual labor and chores in order to free the betters of society into perusing the more important work that must be done. Oroonoko goes from being a warrior and prominent figure in his society to being captured and turned to slavery at his own expense. Oroonoko is seen as unjustly held in bondage as a singular entity rather than as a moral imperative for the evils of slavery in itself.[28]

Gender roles

Despite having little dialogue in Oroonoko, Imoinda is a multifaceted character; she exhibits both traditionally feminine and masculine traits. On one hand, Imoinda is characterized as submissive and frail, for instance, when she faints into Oroonoko’s arms on two occasions. However, when the slaves make an effort to escape from their masters, Imoinda acts as a heroine and injures one of the slave masters that chased after them.[29]

Women

Author

As a member of the "British female transatlantic experience" and an early canonical female author, Aphra Behn's writings have been the subject of various feminist analyses in the years since Oroonoko's publication.[27] Through the eponymous Oroonoko, and other periphery male characters, masculinity is equated with dominance throughout the text, a dominance which is supplemented by feminine power in the form of strong female characters. Behn challenges the predetermined patriarchal norm of favoring the literary merit of male writers simply because of their elite role in society. In her time, Behn's success as a female author enabled the proliferation of respect and high readership for up-and-coming women writers.[27]

As an author who did not endure the brutality of slavery, Behn is considered a duplicitous narrator with dual perspectives according to research from G.A. Starr's "Aphra Behn and the Genealogy of the Man of Feeling". Throughout Behn's early life and literary career, Starr notes that "Behn was in a good position to analyze such a predicament... as a woman-single, poor, unhealthy-supporting herself by writing, and probably a Roman Catholic, she knew about marginality and vulnerability".[30] As evident in this excerpt, Behn's attitude towards the "predicament" of slavery remained ambiguous throughout Oroonoko, due in part to her identity and inexperience with racial discrimination.[30] Despite the fact that this story is told through Behn's perspective as a marginalized female author in a male-dominated literary canon, the cultural complexities of the institution of slavery are still represented through the lens of an outside source.[30]

Throughout the novella, Behn identifies with Oroonoko's strength, courage, and intelligence but also includes herself in the same categorization of the higher European power structure. For example, in Albert Rivero's "Aphra Behn's 'Oroonoko' and the 'Blank Spaces' of Colonial Fictions," the author gives context to Oroonoko within a greater body of colonial fictions. Rivero describes Behn's novella as "the romance of decorous, upper class sentiments".[16] The multi-layered components of Behn's publication parallel her ever-changing perception of racial tension throughout the novella. Behn as a duplicitous narrator plays into the ambiguity of her support for abolition, mixed with the control afforded to her because of her race and economic status.[16]

Imoinda

Imoinda serves as a strong female character in Oroonoko due in part to Behn's emphasis on Imoinda's individuality. Behn's depiction of Imoinda is mostly unrelated to the central plot point within the text; the protagonist's journey of self-discovery. During the era in which the work was written, male heroism dominated the literary field. Most often, protagonist roles were designated to male characters, and with this, the voice of the female remained silent.[31] In this sense, Behn's characterization of Imoinda as a fighter and a lively autonomous woman, despite the cultural climate of slavery and the societal norm to view females as accessories, prompted a sense of female liberation.[31]

Behn's novel awakens the voice of the female that deserves more recognition in literature. Imoinda is Oroonoko's love interest in the novel, but this is not all she is. Rather than falling into the role of the typical submissive female, Imoinda frequently displays that she is strong enough to fight alongside Oroonoko, exemplified by her killing of the governor (Behn 68). Imoinda is portrayed as Oroonoko's equal in the work; where Oroonoko is described as "Mars" (16), Imoinda is described as "the beautiful black Venus" (16). Ultimately, their strengths of aggression and beauty are exemplified through mythological parallels. Comparisons with Mars, the God of war, in the beginning of the novella provides a framework for Oroonoko's rise as an admired warrior, while Imoinda's relation to divinity is more feminine from the start, drawing a connection between her appearance, and that of the powerful Venus, goddess of love and beauty in Roman myth. Imoinda being compared to a goddess of love is fitting of her character, for through reading the novella, readers can easily see that she is a character that is driven by love, particularly hers for Oroonoko. She fights alongside her husband to free themselves from slavery, and to obtain a better life for both themselves and their unborn child. By the end of her life, Imoinda obediently accepts her death at the hands of her husband, along with that of her unborn child, out of love, admiration, and respect for Oroonoko.

By paralleling Imoinda with a Roman goddess, she is given an air of prominence and power, a revolutionary concept in literature at the time. Behn herself was a revolutionary part of seventeenth-century literature, as she played the role of a female author, narrator, and character. Behn bases the story upon her trip to Surinam and, in the beginning of the text, she makes it clear that it is a "true story", presenting Oroonoko as both an anti-slavery and proto-feminist narrative combined.

In regards to Imoinda, In "The White Female as Effigy and the Black Female as Surrogate in Janet. Schaw's Journal of a Lady of Quality and Jane Austen's Mansfield Park" by David S. Wallace, "MacDonald emphasizes the whitening of the character of Imoinda--Oroonoko's wife--in every adaptation of the novella.” Wallace also discusses how Imoinda is hypersexualized in this novel to desexualize white women. Wallace writes: "At least a few white, female authors became agents in this desexualization of white women and hyper-sexualization of their black counterparts."[32]

Sexuality

One of the first attributes allotted to Imoinda in Oroonoko is her stunning and beautiful exterior. Behn depicts her as godlike in appearance, describing her as "the beautiful black Venus" (Behn 16). For example, Behn boasts about the hundreds of European men who are "vain and unsuccessful" (16) in winning her affections. Here, Behn raises Imoinda's appearance and value above the standards of a whitened sense of European beauty. By claiming that these "white men" are unworthy of her attention, she is granted greater merit than them (16). Furthermore, Behn states that Imoinda was of such high prominence that she was "too great for any but a prince of her own nation" (16). Though our female protagonist is once again linked to the male hero here, she is still evidently given an air of dominance over the men Behn describes.[33]

When Imoinda is taken as the King's mistress, she does not give herself to him sexually simply because of his position in society. Though he makes advances towards the young Imoinda, she and the King never consummate their marriage; it isn't until Imoinda reunites with Oroonoko that she feels prepared to give up her virginity (29). With this, Behn connects a female's virtue with her sovereignty, indicating that Imoinda maintains autonomy over her own sexuality.[33]

Imoinda is not the only female protagonist who symbolizes female sexuality. Based on her portrayal of, and attitude towards Oroonoko, Aphra Behn emphasizes the sexual freedom and desires of the female gender. She molds Oroonoko in her own image, depicting him with European features despite his "ebony" flesh (Behn 15). By doing so, she is not only creating a mirror image of herself, a hero who seeks to dismantle the institution of slavery, but she is also embodying the desires of female sexuality.[33] Rob Baum claims that "Behn's attraction to Oroonoko is not engendered by his blackness but despite it" (14) and that she ultimately reveres him, not merely for his heroism, but for his overt physical attractiveness.[33]

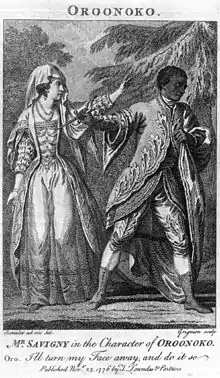

Adaptation

Oroonoko was not a very substantial success at first. The stand-alone edition, according to the English Short Title Catalog online, was not followed by a new edition until 1696. Behn, who had hoped to recoup a significant amount of money from the book, was disappointed. Sales picked up in the second year after her death, and the novel then went through three printings. The story was used by Thomas Southerne for a tragedy entitled Oroonoko: A Tragedy.[34] Southerne's play was staged in 1695 and published in 1696, with a foreword in which Southerne expresses his gratitude to Behn and praises her work. The play was a great success. After the play was staged, a new edition of the novel appeared, and it was never out of print in the 18th century afterward. The adaptation is generally faithful to the novel, with one significant exception: it makes Imoinda white instead of black (see Macdonald), and therefore, like Othello, the male lead would perform in blackface to a white heroine. As the taste of the 1690s demanded, Southerne emphasises scenes of pathos, especially those involving the tragic heroine, such as the scene where Oroonoko kills Imoinda. At the same time, in standard Restoration theatre rollercoaster manner, the play intersperses these scenes with a comic and sexually explicit subplot. The subplot was soon cut from stage representations with the changing taste of the 18th century, but the tragic tale of Oroonoko and Imoinda remained popular on the stage. William Ansah Sessarakoo reportedly left a mid-century performance in tears.

Through the 18th century, Southerne's version of the story was more popular than Behn's, and in the 19th century, when Behn was considered too indecent to be read, the story of Oroonoko continued in the highly pathetic and touching Southerne adaptation. The killing of Imoinda, in particular, was a popular scene. It is the play's emphasis on, and adaptation to, tragedy that is partly responsible for the shift in interpretation of the novel from Tory political writing to prescient "novel of compassion". When Roy Porter writes of Oroonoko, "the question became pressing: what should be done with noble savages? Since they shared a universal human nature, was not civilization their entitlement," he is speaking of the way that the novel was cited by anti-slavery forces in the 1760s, not the 1690s, and Southerne's dramatic adaptation is significantly responsible for this change of focus.[35]

In the 18th century, Oroonoko appears in various German plays:

- Anonymous: Oronocko, oder Der moralisirende [!] Wilde (1757)

- Klinger, Friedrich Maximilian: Der Derwisch. Eine Komödie in fünf Aufzügen (1780)

- Dalberg, Wolfgang Heribert Freiherr von: Oronooko ein Trauerspiel in fünf Handlungen (1786) (an adaptation of Behn)

- Schönwärt: Oronooko, Prinz von Kandien. Trauerspiel in 5 Aufzügen (1780?)

The work was rewritten in the 21st century as IMOINDA Or She Who Will Lose Her Name (2008) by Professor Joan Anim-Addo. The rewriting focuses on the story of Imoinda.

In 2012, a play by Biyi Bandele based on Oroonoko was performed by the Royal Shakespeare Company at The Other Place.[36]

Notes

- ↑ Benítez-Rojo, Antonio (2018). "The Caribbean: From a Sea Basin to an Atlantic Network". The Southern Quarterly. 55: 196–206.

- ↑ Woolf, Virginia (1929). A Room of One's Own. Harcourt.

- ↑ Janet Todd, 'Behn, Aphra (1640?–1689)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 31 March 2016

- ↑ Hutner 1993, p. 1.

- 1 2 Todd, 38

- ↑ Todd, 40

- ↑ Todd, 54

- 1 2 Exact Relation, quoted in Todd, 55

- 1 2 3 Todd, 61

- ↑ Hughes, Derek (2007). Versions of Blackness. Cambridge University Press. p. xviii. ISBN 978-0-521-68956-4.

- ↑ Iwanisziw, Susan B. (1998). "Behn's Novel Investment in "Oroonoko": Kingship, Slavery and Tobacco in English Colonialism". South Atlantic Review. 63 (2): 75–98. doi:10.2307/3201039. ISSN 0277-335X. JSTOR 3201039.

- ↑ Todd, 61–63

- ↑ Todd, 70

- 1 2 3 4 5 Campbell, Mary (1999). ""My Travels to the Other World": Aphra Behn and Surinam". Wonder and Science: Imagining Worlds in Early Modern Europe. Cornell University Press. pp. 257–84.

- ↑ Pincus, Steve (2009). "English Politics at the Accession of James II". 1688: The First Modern Revolution. Yale University Press. pp. 91–117. ISBN 9780300115475.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Rivero, Albert J. (1999). "Aphra Behn's 'Oroonoko' and the 'Blank Spaces' of Colonial Fictions". Studies in English Literature. 39 (3): 443–62. doi:10.1353/sel.1999.0029. S2CID 162219993.

- ↑ Todd, 3

- ↑ Behn, Gallagher, and Stern, 13

- ↑ Behn, 38

- 1 2 3 Behn, Gallagher, and Stern, 15

- ↑ Behn, 40

- ↑ Behn, Gallagher, and Stern, 14

- ↑ Mallipeddi, Ramesh (2012). "Spectacle, Spectatorship, and Sympathy in Aphra Behn's Oroonoko". Eighteenth-Century Studies. 45 (4): 475–96. doi:10.1353/ecs.2012.0047. S2CID 163033074.

- ↑ Stephen Greenblatt; et al., eds. (2012). The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Volume C: The Restoration and The Eighteenth Century. W. W. Norton and Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0393912517.

- 1 2 Conway, Alison (Spring 2003). "Flesh on the Mind: Behn Studies in the New Millennium". The Eighteenth Century. 44.

- ↑ Pacheco, Anita (1994). "Royalism and Honor in Aphra Behn's Oroonoko". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 34 (3): 491–506. doi:10.2307/450878. ISSN 0039-3657. JSTOR 450878.

- 1 2 3 Tasker-Davis, Elizabeth (2011). "Cosmopolitan Benevolence from a Female Pen: Aphra Behn and Charlotte Lennox Remember the New World". South Atlantic Review. 76 (1): 33–51. JSTOR 41635670.

- ↑ Ferguson, Moira (20 March 1992). "Oroonoko: Birth of a Paradigm". New Literary History. 23 (2): 339–359. doi:10.2307/469240. JSTOR 469240.

- ↑ Tirado, Ana Ruano (5 July 2016). "Racial and Gender Dichotomies in Aphra Behn's Oroonoko or the Royal Slave".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 Starr, G. A. (1990). "Aphra Behn and the Genealogy of the Man of Feeling". Modern Philology. 87 (4): 362–72. doi:10.1086/391801. JSTOR 438558. S2CID 162246311.

- 1 2 Andrade, Susan Z. (1994). "White Skin, Black Masks: Colonialism and the Sexual Politics of Oroonoko". Cultural Critique (27): 189–214. doi:10.2307/1354482. JSTOR 1354482.

- ↑ Wallace, David S. (2014). "The White Female as Effigy and the Black Female as Surrogate in Janet. Schaw's Journal of a Lady of Quality and Jane Austen's Mansfield Park". Studies in the Literary Imagination. 47 (2): 117–130. doi:10.1353/sli.2014.0009. S2CID 201796498.

- 1 2 3 4 Baum, Rob (2011). "Aphra Behn's Black Body: Sex, Lies & Narrativity in Oroonoko". Brno Studies in English. 37 (2): 13–14. doi:10.5817/BSE2011-2-2.

- ↑ Messenger, Ann (1986). "Novel Into Play". His and Hers: Essays in Restoration and 18th-Century Literature. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 41–70.

- ↑ Porter 361.

- ↑ "Oroonoko By Biyi Bandele". Black Plays Archive. National Theatre. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

References

- Alarcon, Daniel Cooper and Athey, Stephanie (1995). Oroonoko's Gendered Economies of Honor/Horror: Reframing Colonial Discourse Studies in the Americas. Duke University Press.

- An Exact Relation of The Most Execrable Attempts of John Allin, Committed on the Person of His Excellency Francis Lord Willoughby of Parham. . . . (1665), quoted in Todd 2000.

- Baum, Rob, "Aphra Behn's Black Body: Sex, Lies & Narrativity in Oroonoko." Brno Studies in English, vol. 37, no. 2, 2011, pp. 13–14.

- Behn, Aphra. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 19 March 2005

- Behn, Aphra, and Janet Todd. Oroonoko. The Rover. Penguin, 1992. ISBN 978-0-140-43338-8

- Behn, A., Gallagher, C., & Stern, S. (2000). Oroonoko, or, The royal slave. Bedford cultural editions. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's.

- Bernbaum, Ernest (1913). "Mrs. Behn's Oroonoko" in George Lyman Kittredge Papers. Boston, pp. 419–33.

- Brown, Laura (1990). Romance of empire: Oroonoko and the trade in slaves. St. Martin's Press, Scholarly and Reference Division, New York.

- Dhuicq, Bernard (1979). "Additional Notes on Oroonoko", Notes & Queries, pp. 524–26.

- Ferguson, Margaret W. (1999). Juggling the Categories of Race, Class and Gender: Aphra Behn's Oroonoko. St. Martin's Press, Scholarly and Reference Division, New York.

- Hughes, Derek (2007). Versions of Blackness: Key Texts on Slavery from the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68956-4

- Hutner, Heidi (1993). Rereading Aphra Behn: history, theory, and criticism. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-1443-4

- Klein, Martin A. (1983). Women and Slavery in Africa. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Macdonald, Joyce Green (1998). "Race, Women, and the Sentimental in Thomas Southerne's Oroonoko", Criticism 40.

- Moulton, Charles Wells, ed. (1959). The Library of Literary Criticism. Volume II 1639–1729. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith.

- Parker, Matthew (2015). Willoughbyland: England's lost colony. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0091954096

- Porter, Roy (2000). The Creation of the Modern World. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-32268-8

- Ramsaran, J. A. (1960). "Notes on Oroonoko". Notes & Queries, p. 144.

- Rivero, Albert J. "Aphra Behn's 'Oroonoko' and the 'Blank Spaces' of Colonial Fictions." SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900, vol. 39, no. 3, 1999, pp. 451. JSTOR 1556214.

- Stassaert, Lucienne (2000). De lichtvoetige Amazone. Het geheime leven van Aphra Behn. Leuven: Davidsfonds/Literair. ISBN 90-6306-418-7

- Todd, Janet (2000). The Secret Life of Aphra Behn. London: Pandora Press.

External links

- Oroonoko; or, The Royal Slave, Literature in Context: An Open Anthology of Literature. 2019. Web.

- Oroonoko, scanned pages of a seventeenth-century edition of the theatrical adaptation by Thomas Southerne.

Oroonoko public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Oroonoko public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Lecture: Behn's Oroonoko: ethnography, romance and history, by professor William Warner at the University of California Santa Barbara.

- An Annotated Bibliography on Aphra Behn's Oroonoko, by Jack Lynch, 1997.

Further reading

- Altaba-Artal, Dolors (1999). Aphra Behn's English feminism : wit and satire. Selinsgrove, PA: Susquehanna University Press. ISBN 1-57591-029-2. OCLC 41355826.

- Todd, Janet (1996) Aphra Behn Studies. Great Britain: University Press, Cambridge.

- Backscheider, Paula R. (1999-02). "Aphra Behn Studies. Janet Todd, Aphra Behn". Modern Philology. 96 (3): 384–387. doi:10.1086/492770. ISSN 0026-8232

- Sim, Stuart (2008) Oroonoko, or, The History of the Royal Slave and Race Relations. Edinburgh University Press

- Beach, Adam R. (2010) Behn's Oroonoko, the Gold Coast, and Slavery in the Early-Modern Atlantic World. Johns Hopkins University Press