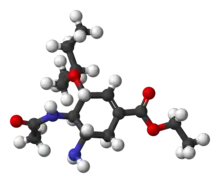

Oseltamivir total synthesis concerns the total synthesis of the antiinfluenza drug oseltamivir[1] marketed by Hoffmann-La Roche under the trade name Tamiflu. Its commercial production starts from the biomolecule shikimic acid harvested from Chinese star anise and from recombinant E. coli.[2][3] Control of stereochemistry is important: the molecule has three stereocenters and the sought-after isomer is only 1 of 8 stereoisomers.

Commercial production

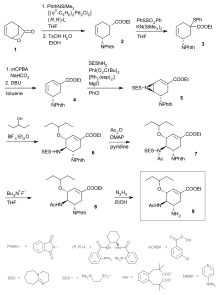

The current production method is based on the first scalable synthesis developed by Gilead Sciences[4] starting from naturally occurring quinic acid or shikimic acid. Due to lower yields and the extra steps required (because of the additional dehydration), the quinic acid route was dropped in favour of the one based on shikimic acid, which received further improvements by Hoffmann-La Roche.[5][6] The current industrial synthesis is summarised below:

Karpf / Trussardi synthesis

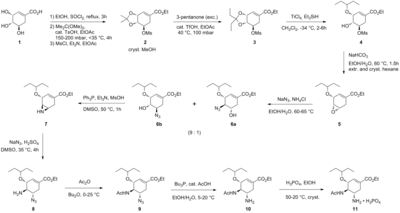

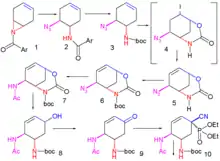

The current production method includes two reaction steps with potentially hazardous azides. A reported azide-free Roche synthesis of tamiflu is summarised graphically below:[7]

The synthesis commences from naturally available (−)-shikimic acid. The 3,4-pentylidene acetal mesylate is prepared in three steps: esterification with ethanol and thionyl chloride; ketalization with p-toluenesulfonic acid and 3-pentanone; and mesylation with triethylamine and methanesulfonyl chloride. Reductive opening of the ketal under modified Hunter conditions[8] in dichloromethane yields an inseparable mixture of isomeric mesylates. The corresponding epoxide is formed under basic conditions with potassium bicarbonate. Using the inexpensive Lewis acid magnesium bromide diethyl etherate (commonly prepared fresh by the addition of magnesium turnings to 1,2-dibromoethane in benzene:diethyl ether), the epoxide is opened with allyl amine to yield the corresponding 1,2-amino alcohol. The water-immiscible solvents methyl tert-butyl ether and acetonitrile are used to simplify the workup procedure, which involved stirring with 1 M aqueous ammonium sulfate. Reduction on palladium, promoted by ethanolamine, followed by acidic workup yielded the deprotected 1,2-aminoalcohol. The aminoalcohol was converted directly to the corresponding allyl-diamine in an interesting cascade sequence that commences with the unselective imination of benzaldehyde with azeotropic water removal in methyl tert-butyl ether. Mesylation, followed by removal of the solid byproduct triethylamine hydrochloride, results in an intermediate that was poised to undergo aziridination upon transimination with another equivalent of allylamine. With the librated methanesulfonic acid, the aziridine opens cleanly to yield a diamine that immediately undergoes a second transimination. Acidic hydrolysis then removed the imine. Selective acylation with acetic anhydride (under buffered conditions, the 5-amino group is protonated owing to a considerable difference in pKa, 4.2 vs 7.9, preventing acetylation) yields the desired N-acetylated product in crystalline form upon extractive workup. Finally, deallylation as above, yielded the freebase of oseltamivir, which was converted to the desired oseltamivir phosphate by treatment with phosphoric acid. The final product is obtained in high purity (99.7%) and an overall yield of 17-22% from (−)-shikimic acid. It is noted that the synthesis avoids the use of potentially explosive azide reagents and intermediates; however, the synthesis actually used by Roche uses azides. Roche has other routes to oseltamivir that do not involve the use of (−)-shikimic acid as a chiral pool starting material, such as a Diels-Alder route involving furan and ethyl acrylate or an isophthalic acid route, which involves catalytic hydrogenation and enzymatic desymmetrization.

Corey synthesis

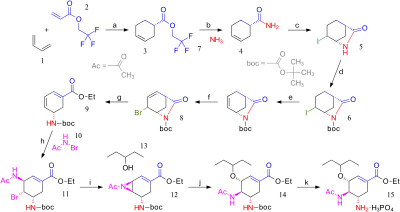

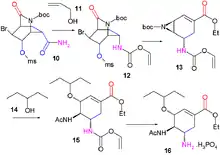

In 2006 the group of E.J. Corey published a novel route bypassing shikimic acid starting from butadiene and acrylic acid.[9] The inventors chose not to patent this procedure which is described below.

Butadiene 1 reacts in an asymmetric Diels-Alder reaction with the esterification product of acrylic acid and 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol 2 catalysed by the CBS catalyst. The ester 3 is converted into an amide in 4 by reaction with ammonia and the next step to lactam 5 is an iodolactamization with iodine initiated by trimethylsilyltriflate. The amide group is fitted with a BOC protecting group by reaction with Boc anhydride in 6 and the iodine substituent is removed in an elimination reaction with DBU to the alkene 7. Bromine is introduced in 8 by an allylic bromination with NBS and the amide group is cleaved with ethanol and caesium carbonate accompanied by elimination of bromide to the diene ethyl ester 9. The newly formed double bond is functionalized with N-bromoacetamide 10 catalyzed with tin(IV) bromide with complete control of stereochemistry. In the next step the bromine atom in 11 is displaced by the nitrogen atom in the amide group with the strong base KHMDS to the aziridine 12 which in turn is opened by reaction with 3-pentanol 13 to the ether 14. In the final step the BOC group is removed with phosphoric acid and the oseltamivir phosphate 15 is formed.

Shibasaki synthesis

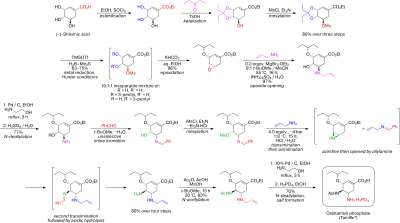

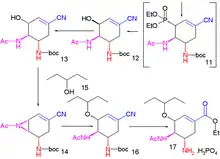

Also in 2006 the group of Masakatsu Shibasaki of the University of Tokyo published a synthesis again bypassing shikimic acid.[10][11]

An improved method published in 2007 starts with the enantioselective desymmetrization of aziridine 1 with trimethylsilyl azide (TMSN3) and a chiral catalyst to the azide 2. The amide group is protected as a BOC group with Boc anhydride and DMAP in 3 and iodolactamization with iodine and potassium carbonate first gives the unstable intermediate 4 and then stable cyclic carbamate 5 after elimination of hydrogen iodide with DBU.

The amide group is reprotected as BOC 6 and the azide group converted to the amide 7 by reductive acylation with thioacetic acid and 2,6-lutidine. Caesium carbonate accomplishes the hydrolysis of the carbamate group to the alcohol 8 which is subsequently oxidized to ketone 9 with Dess-Martin periodinane. Cyanophosphorylation with diethyl phosphorocyanidate (DEPC) modifies the ketone group to the cyanophosphate 10 paving the way for an intramolecular allylic rearrangement to unstable β-allyl phosphate 11 (toluene, sealed tube) which is hydrolyzed to alcohol 12 with ammonium chloride. This hydroxyl group has the wrong stereochemistry and is therefore inverted in a Mitsunobu reaction with p-nitrobenzoic acid followed by hydrolysis of the p-nitrobenzoate to 13.

A second Mitsunobu reaction then forms the aziridine 14 available for ring-opening reaction with 3-pentanol catalyzed by boron trifluoride to ether 15. In the final step the BOC group is removed (HCl) and phosphoric acid added to objective 16.

Fukuyama synthesis

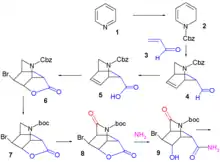

An approach published in 2007[12] like Corey's starts by an asymmetric Diels-Alder reaction this time with starting materials pyridine and acrolein.

Pyridine (1) is reduced with sodium borohydride in presence of benzyl chloroformate to the Cbz protected dihydropyridine 2. The asymmetric Diels-Alder reaction with acrolein 3 is carried out with the McMillan catalyst to the aldehyde 4 as the endo isomer which is oxidized to the carboxylic acid 5 with sodium chlorite, monopotassium phosphate and 2-methyl-2-butene. Addition of bromine gives halolactonization product 6 and after replacement of the Cbz protective group by a BOC protective group in 7 (hydrogenolysis in the presence of di-tert-butyl dicarbonate) a carbonyl group is introduced in intermediate 8 by catalytic ruthenium(IV) oxide and sacrificial catalyst sodium periodate. Addition of ammonia cleaves the ester group to form amide 9 the alcohol group of which is mesylated to compound 10. In the next step iodobenzene diacetate is added, converting the amide in a Hofmann rearrangement to the allyl carbamate 12 after capturing the intermediate isocyanate with allyl alcohol 11. On addition of sodium ethoxide in ethanol three reactions take place simultaneously: cleavage of the amide to form new an ethyl ester group, displacement of the mesyl group by newly formed BOC protected amine to an aziridine group and an elimination reaction forming the alkene group in 13 with liberation of HBr. In the final two steps the aziridine ring is opened by 3-pentanol 14 and boron trifluoride to aminoether 15 with the BOC group replaced by an acyl group and on removal of the other amine protecting group (Pd/C, Ph3P, and 1,3-dimethylbarbituric acid in ethanol) and addition of phosphoric acid oseltamivir 16 is obtained.

Trost synthesis

In 2008 the group of Barry M. Trost of Stanford University published the shortest synthetic route to date.[13]

Hayashi synthesis

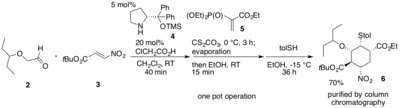

In 2009, Hayashi et al. successfully produced an efficient, low cost synthetic route to prepare (-)-oseltamivir (1). Their goal was to design a procedure that would be suitable for large-scale production. Keeping cost, yield, and number of synthetic steps in mind, an enantioselective total synthesis of (1) was accomplished through three one-pot operations.[14][5] Hayashi et al.'s use of one-pot operations allowed them to perform several reactions steps in a single pot, which ultimately minimized the number of purification steps needed, waste, and saved time.

In the first one-pot operation, Hayashi et al. begins by using diphenylprolinol silyl ether (4)[6] as an organocatalyst, along with alkoxyaldehyde (2) and nitroalkene (3) to perform an asymmetric Michael reaction, affording an enantioselective Michael adduct. Upon addition of a diethyl vinylphosphate derivative (5) to the Michael adduct, a domino Michael reaction and Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons reaction occurs due to the phosphonate group produced from (5) to give an ethyl cyclohexenecarboxylate derivative along with two unwanted by-products. To transform the undesired by-products into the desired ethyl cyclohexencarboxylate derivative, the mixture of the product and by-products was treated with Cs2CO3 in ethanol. This induced a retro-Michael reaction on one by-product and a retro-aldol reaction accompanied with a Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons reaction for the other. Both by-products were successfully converted to the desired derivative. Finally, the addition of p-toluenethiol with Cs2CO3 gives (6) in a 70% yield after being purified by column chromatography, with the desired isomer dominating.[14]

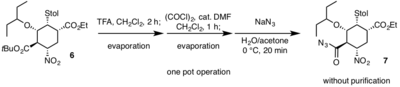

In the second one-pot operation, trifluoroacetic acid is employed first to deprotect the tert-butyl ester of (6); any excess reagent was removed via evaporation. The carboxylic acid produced as a result of the deprotection was then converted to an acyl chloride by oxalyl chloride and a catalytic amount of DMF. Finally, addition of sodium azide, in the last reaction of the second one-pot operation, produce the acyl azide (7) without any purification needed.[14]

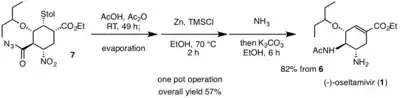

The final one-pot operation begins with a Curtius Rearrangement of acyl azide (7) to produce an isocyanate functional group at room temperature. The isocyanate derivative then reacts with acetic acid to yield the desired acetylamino moiety found in (1). This domino Curtius rearrangement and amide formation occurs in the absence of heat, which is extremely beneficial for reducing any possible hazard. The nitro moiety of (7) is reduced to the desired amine observed in (1) with Zn/HCl. Due to the harsh conditions of the nitro reduction, ammonia was used to neutralize the reaction. Potassium carbonate was then added to give (1), via a retro-Michael reaction of the thiol. (1) was then purified by an acid/base extraction. The overall yield for the total synthesis of (-)-oseltamivir is 57%.[14] Hayashi et al. use of inexpensive, non-hazardous reagents has allowed for an efficient, high yielding synthetic route that can allow for vast amount of novel derivatives to be produced in hopes of combatting against viruses resistant to (-)-oseltamivir.

References

- ↑ Classics in Total Synthesis III: Further Targets, Strategies, Methods K. C. Nicolaou, Jason S. Chen ISBN 978-3-527-32957-1 2011

- ↑ Farina V, Brown JD (November 2006). "Tamiflu: the supply problem". Angewandte Chemie. 45 (44): 7330–4. doi:10.1002/anie.200602623. PMID 17051628.

- ↑ Rawat G, Tripathi P, Saxena RK (May 2013). "Expanding horizons of shikimic acid. Recent progresses in production and its endless frontiers in application and market trends". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 97 (10): 4277–87. doi:10.1007/s00253-013-4840-y. PMID 23553030. S2CID 17660413.

- ↑ Rohloff John C.; Kent Kenneth M.; Postich Michael J.; Becker Mark W.; Chapman Harlan H.; Kelly Daphne E.; Lew Willard; Louie Michael S.; McGee Lawrence R.; et al. (1998). "Practical Total Synthesis of the Anti-Influenza Drug GS-4104". J. Org. Chem. 63 (13): 4545–4550. doi:10.1021/jo980330q.

- 1 2 Laborda, Pedro; Wang, Su-Yan; Voglmeir, Josef (2016-11-11). "Influenza Neuraminidase Inhibitors: Synthetic Approaches, Derivatives and Biological Activity". Molecules. 21 (11): 1513. doi:10.3390/molecules21111513. PMC 6274581. PMID 27845731.

- 1 2 Hayashi, Yujiro; Gotoh, Hiroaki; Hayashi, Takaaki; Shoji, Mitsuru (2005-07-04). "Diphenylprolinol Silyl Ethers as Efficient Organocatalysts for the Asymmetric Michael Reaction of Aldehydes and Nitroalkenes". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 44 (27): 4212–4215. doi:10.1002/anie.200500599. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 15929151.

- ↑ Karpf, M; Trussardi, R (March 2001). "New, azide-free transformation of epoxides into 1,2-diamino compounds: synthesis of the anti-influenza neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir phosphate (Tamiflu)". J. Org. Chem. 66 (6): 2044–51. doi:10.1021/jo005702l. PMID 11300898..

- ↑ Birgit Bartels; Roger Hunter (1993). "A selectivity study of activated ketal reduction with borane dimethyl sulfide". J. Org. Chem. 58 (24): 6756–6765. doi:10.1021/jo00076a041.

- ↑ Yeung, Ying-Yeung; Hong, Sungwoo; Corey, E. J. (2006). "A Short Enantioselective Pathway for the Synthesis of the Anti-Influenza Neuramidase Inhibitor Oseltamivir from 1,3-Butadiene and Acrylic Acid". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (19): 6310–6311. doi:10.1021/ja0616433. PMID 16683783. S2CID 20852603.

- ↑ Fukuta, Yuhei (2006). "De Novo Synthesis of Tamiflu via a Catalytic Asymmetric Ring-Opening of meso -Aziridines with TMSN 3". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 128 (19): 6312–6313. doi:10.1021/ja061696k. PMID 16683784.

- ↑ Mita, Tsuyoshi (2007). "Second Generation Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Tamiflu: Allylic Substitution Route". Organic Letters. 9 (2): 259–262. doi:10.1021/ol062663c. PMID 17217279.

- ↑ Satoh, Nobuhiro (2007). "A Practical Synthesis of (−)-Oseltamivir". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 46 (30): 5734–5736. doi:10.1002/anie.200701754. PMID 17594704.

- ↑ Trost, Barry M. (2008). "A Concise Synthesis of (−)-Oseltamivir". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 47 (20): 3759–3761. doi:10.1002/anie.200800282. PMID 18399551.

- 1 2 3 4 Ishikawa, Hayato; Suzuki, Takaki; Hayashi, Yujiro (2009-02-02). "High-Yielding Synthesis of the Anti-Influenza Neuramidase Inhibitor (−)-Oseltamivir by Three "One-Pot" Operations". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 48 (7): 1304–1307. doi:10.1002/anie.200804883. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 19123206.