Osferth or Osferd or Osfrith[lower-alpha 1] (fl. c. 885 to c. 934) was described by Alfred the Great in his will as a "kinsman". Osferth witnessed royal charters from 898 to 934, as an ealdorman between 926 and 934. In a charter of Edward the Elder, he was described as a brother of the king. Therefore, Janet Nelson argues that he was probably an illegitimate son of Alfred. Simon Keynes and Michael Lapidge suggest that he may have been a relative of Alfred's mother Osburh, or a son of Oswald filius regis (king's son), who in turn may have been a son of Alfred's elder brother and predecessor as king, Æthelred I.

Life

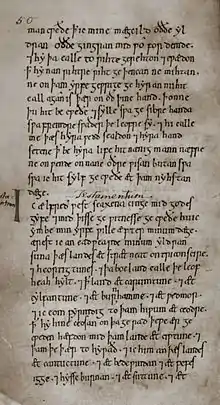

Osferth is first recorded in the will of Alfred the Great, King of the Anglo-Saxons, which probably dates to the mid-880s.[2] Alfred bequeathed "to my kinsman Osferth" estates at Beckley, Rotherfield, Ditchling, Sutton, Lyminster, Angmering and Felpham. Ditchling and Lyminster were substantial royal estates,[3] and all the properties are in Sussex. Janet Nelson suggests that they may have been "the core of a South Saxon subkingdom". The bequest was more generous than that to Æthelwold, who was the younger son of Alfred's elder brother and predecessor, Æthelred, and more compact than that to Æthelred's elder son, Æthelhelm. In a royal charter of 898 Osferth witnessed second in the list of ministri (king's thegns).[4] Alfred died in 899, and in a charter of 901 he witnessed without a title second after King Edward,[5] and in 903 again without title immediately after Edward's brother Æthelweard.[6] In a charter of 904 he witnessed above Plegmund, Archbishop of Canterbury, and next after "Æthelweard filius regis" (king's son) as "Osferd frater regis" (king's brother).[7] In a doubtful charter of 909 he is listed straight after Edward's son Ælfweard as propinquus regis (king's kinsman).[8] Osferth witnesses as dux (ealdorman) in two dubious charters of 909,[9] but there are no surviving charters for the last fifteen years of Edward's reign, and Osferth appears from 926 to 934 at or near the top of lay witnesses as an ealdorman.[lower-alpha 2] At an unknown date, probably early in Edward's reign, he was a signatory to the settlement of the dispute outlined in the Fonthill Letter.[22] Nelson comments: "Clearly Osferth held an exceptionally prominent position at the courts of three successive kings. It is a sobering thought that none of the narrative sources mention him at all."[23]

Parentage

According to Keynes and Lapidge, Osferth was described as Edward's brother "mistakenly" (in Nelson's view "with a briskness worthy of the late Dorothy Whitelock herself"). They say: "Osferth's relationship to Alfred is uncertain. He may have belonged to his mother Osburh's family, or he may have been a son of the Oswald filius regis who occurs in [royal charters] S 340, 1201 and 1203 and was perhaps a son of Alfred's brother Æthelred."[24] However, in Nelson's view, it is very unlikely that Oswald was Æthelred's son. She points out that in the introduction to Alfred's will he says that on his succession to the throne there were complaints about his treatment of Æthelred's sons, "the older and the younger", meaning Æthelhelm and Æthelwold. This suggests that only two sons were alive in 871, but Oswald witnessed in 875. She argues that in view of Osferth's place in Alfred's will and his high position in witness lists in Edward's and Æthelstan's reigns, he may have been Alfred's illegitimate son. In the ninth century moralists were increasingly condemning sex outside marriage, and Alfred suffered such anxiety over his sexuality that he prayed for an illness that would inhibit lust. Nelson argues that the existence of an illegitimate son would explain the depth of his concern: Asser's failure to mention Osferth in his Life of Alfred is not surprising as he aimed to portray Alfred as a faithful husband.[25] In his biography of Alfred, Richard Abels points out that the 'Os-' prefix was common in Alfred's maternal ancestry, and suggests that Osferth belonged to that side of the family, but also mentioned Nelson's view favourably in a footnote.[26]

Notes

- ↑ Osferth is recorded as Osfrith in the Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England[1]

- ↑ Nelson lists the charters which Osferth witnessed in Æthelstan's reign.[10] He is listed third among the ealdormen in a charter of 926;[11] he is second among lay witnesses in charters of 931[12] and 932,[13] and two charters of 934;[14] he is first among lay witnesses in a charter of 928,[15] two charters of 929,[16] one of 930,[17] two of 931,[18] one of 932,[19] one of 933[20] and one of 931/4.[21]

Citations

- ↑ Osfrith 8 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England

- ↑ Abels, p. 92; Keynes and Lapidge, p. 313

- ↑ Keynes and Lapidge, pp. 177, 322–323

- ↑ S 350

- ↑ S 364

- ↑ S 367

- ↑ S 1286

- ↑ S 378

- ↑ S 375 and 376

- ↑ Nelson, p. 60 n.74

- ↑ S 396

- ↑ S 416

- ↑ S 417

- ↑ S 407 and 425

- ↑ S 400

- ↑ S 401 and 402

- ↑ S 403

- ↑ S 412 and 413

- ↑ S 418

- ↑ S 422

- ↑ S 393

- ↑ Whitelock, document 102, p. 503

- ↑ Nelson, p. 60

- ↑ Keynes and Lapidge, p. 322; Nelson, p. 60

- ↑ Nelson, pp. 47, 59–62

- ↑ Abels, pp. 48, 97 n.27, 272

Bibliography

- Abels, Richard (1998). Alfred the Great: War, Kingship and Culture in Anglo-Saxon England. Harlow, UK: Longman. ISBN 0-582-04047-7.

- Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael, eds. (1983). Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred & Other Contemporary Sources. London, UK: Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-044409-4.

- Nelson, Janet (1996). "Reconstructing a Royal Family: Reflections on Alfred from Asser". In Wood, Ian; Lund, Niels (eds.). People and Places in Northern Europe 500-1600: Essays in Honour of Peter Hayes Sawyer. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. pp. 48–66. ISBN 9780851155470.

- Whitelock, Dorothy, ed. (1955). English Historical Documents c. 500-1042. Vol. 1. London, UK: Eyre & Spottiswoode. ISBN 978-0-413-32490-0.