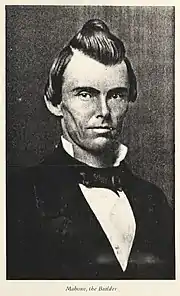

William Mahone | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Virginia | |

| In office March 4, 1881 – March 4, 1887 | |

| Preceded by | Robert E. Withers |

| Succeeded by | John W. Daniel |

| Member of the Virginia Senate from Norfolk City | |

| In office 1863–1865 | |

| Preceded by | William N. McKenney |

| Succeeded by | Edmund Robinson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 1, 1826 Southampton County, Virginia |

| Died | October 8, 1895 (aged 68) Washington, D.C. |

| Resting place | Blandford Cemetery, Petersburg, Virginia |

| Political party | Readjuster (1877–1889) Republican (1889–1895) |

| Alma mater | Virginia Military Institute |

| Nickname | Little Billy |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War (1861-1865) |

William Mahone (December 1, 1826 – October 8, 1895) was an Confederate States Army General, civil engineer, railroad executive, prominent Virginia Readjuster and ardent supporter of former slaves.[1]

As a young man, Mahone was prominent in building Virginia's roads and railroads. As chief engineer of the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad, he built log-foundations under the routes in the Great Dismal Swamp in southeast tidewater Virginia that are still intact today. According to local tradition, several new railroad towns were named after the novels of Sir Walter Scott, a favorite British/Scottish author of Mahone's wife, Otelia.

In the American Civil War, Mahone was pro-secession and served as a general in the Confederate States Army. He was best known for regaining the initiative at the late war siege of Petersburg, Virginia, while Confederate troops were in shock after a huge mine/load of black powder kegs was exploded beneath them by tunnel-digging former coal miner Union Army troops resulting in the Battle of the Crater in July 1864; his counter-attack turned the engagement into a disastrous Union defeat.

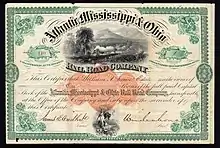

After the war, he returned to railroad building, merging three lines to form the important Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad (AM&O), headquartered in Lynchburg. He also led the Readjuster Party, a state political party with a coalition of freemen blacks, Republicans, and populist Democrats. The Virginia General Assembly elected Mahone to the U.S. Senate in 1881.

Early life

William Mahone was born at Brown's Ferry near Courtland in Southampton County, Virginia, to Fielding Jordan Mahone and Martha (née Drew) Mahone.[2] Beginning with the immigration of his Mahone ancestors from Ireland, he was the third individual to be called "William Mahone". He did not have a middle name as shown by records including his two Bibles, Virginia Military Institute (VMI) diploma, marriage license, and Confederate Army commissions. Likewise, the General and Otelia's first-born son was christened William Mahone. During similar cultural naming transitions in Virginia, the suffix "Jr." was added to his name later.

The little town of Monroe was on the banks of the Nottoway River about eight miles south of the county seat at Jerusalem, a town which was renamed Courtland in 1888. The river was a vital transportation artery in the years before railroads, and later highways served the area. Fielding Mahone ran a store at Monroe and owned considerable farmland. He also enslaved several people for their forced labor.[3] The family narrowly escaped the killings of local whites during Nat Turner's slave rebellion in 1831.

The local transportation shift in the area was from the river to the new technology emerging with railroads in the 1830s. In 1840, when William was 14 years old, the family moved to Jerusalem, where Fielding Mahone purchased and operated a tavern known as Mahone's Tavern.[4] As recounted by his biographer, Nelson Blake, the freckled-faced youth of Irish-American heritage gained a reputation in the small town for both "gambling and a prolific use of tobacco and profanity".

Young Billy Mahone gained his primary education from a country schoolmaster but with special instruction in mathematics from his father. As a teenager, for a short time, he transported the U. S. Mail by horseback from his hometown to Hicksford, a small town on the south bank of the Meherrin River in Greensville County, which later combined with the town of Belfield on the north bank to form the current independent city of Emporia. He was awarded a spot as a state cadet at the recently opened Virginia Military Institute (VMI) in Lexington, Virginia.[5] Studying under VMI Commandant William Gilham, he graduated with a degree as a civil engineer in the Class of 1847.

Early career

Mahone worked as a teacher at Rappahannock Academy in Caroline County, Virginia, beginning in 1848, but was actively seeking an entry into civil engineering. He did some work helping locate the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, an 88-mile line between Gordonsville, Virginia, and the City of Alexandria.[6] Having performed well with the new railroad, was hired to build a plank road between Fredericksburg and Gordonsville.[7][8]

On April 12, 1853, he was hired by Dr. Francis Mallory of Norfolk, as chief engineer to build the new Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad (N&P).[9] William Mahone, chief engineer, advertised for contractors who would regrade the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad for 62 miles from the Warwick Swamp of the Blackwater River to Norfolk in 1853.[10] Mahone's innovative 12-mile-long roadbed through the Great Dismal Swamp between South Norfolk and Suffolk employed a log foundation laid at right angles beneath the surface of the swamp. Still in use over 160 years later, Mahone's corduroy design withstands the immense tonnages of modern coal trains. He was also responsible for engineering and building the famous 52-mile-long tangent track between Suffolk and Petersburg. With no curves, it is a major modern Norfolk Southern rail traffic artery.

In 1854, Mahone surveyed and laid out with streets and lots of Ocean View City, a new resort town fronting on the Chesapeake Bay in Norfolk County.[11] With the advent of electric streetcars in the late 19th century, an amusement park was developed there, and a boardwalk was built along the adjacent beach area. Most of Mahone's street plan is still in use in the 21st century as Ocean View, now a section of the City of Norfolk is redeveloped.

Mahone was also a surveyor for the Norfolk and South Air Line Railroad on the Eastern Shore of Virginia.[11]

Marriage and family

On February 8, 1855, Mahone married Otelia Butler (1835–1911), the daughter of the late Dr. Robert Butler from Smithfield, who had been State Treasurer of the Commonwealth of Virginia from 1846 until he died in 1853.[12] Her mother was Butler's second wife, Otelia Voinard Butler (1803–1855), originally from Petersburg.[7]

Young Otelia Butler is said to have been a cultured lady. She and William settled in Norfolk, where they lived most of the years before the Civil War. They had 13 children, but only three survived to adulthood, two sons, William Jr. and Robert, and a daughter, also named Otelia. From 1862 to 1868, the family resided in Clarksville, Virginia at the Judge Henry Wood Jr. House.[13]

The Mahone family escaped the yellow fever epidemic that broke out in the summer of 1855 and killed almost a third of the populations of Norfolk and Portsmouth by fleeing the city and staying with his mother 50 miles away in Jerusalem (now known as Courtland) in rural Southampton County. However, because the epidemic decimated the Norfolk area, with financial consequences as well, work on the new railroad to Petersburg almost came to a standstill.

Ever frugal, Mahone and his mentor, Dr. Mallory, nevertheless pushed the project to completion in 1858, and Mahone was named its president a short time later. Popular legend claimed Otelia and William Mahone traveled along the newly completed railroad, naming stations from Ivanhoe and other books she was reading written by Sir Walter Scott. From his historical Scottish novels, she chose the place names of Windsor, Waverly, and Wakefield. She tapped the Scottish Clan "McIvor" for the name of Ivor, a small Southampton County town. When they reached a location where they could not agree, Disputanta was created.

American Civil War

.jpg.webp)

As the political differences between Northern and Southern United States factions escalated in the second half of the 19th century, Mahone favored southern states' secession. During the American Civil War, he was active in the conflict even before he became an officer in the Confederate Army. Early in the war, in 1861, his Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad was especially valuable to the Confederacy and transported ordnance to the Norfolk area, where it was used during the Confederate occupation. By the war's end, most of what was left of the railroad was under U.S. control.

After Virginia declared secession from the United States in April 1861, Mahone was still a civilian and not yet in the Confederate Army. Still, working in coordination with Walter Gwynn, he orchestrated the ruse and capture of the Gosport Shipyard. He bluffed U.S. Army troops into abandoning the shipyard in Portsmouth by running a single passenger train into Norfolk with great noise and whistle-blowing, then much more quietly sending it back west and then returning the same train, creating the illusion of large numbers of arriving troops to the U.S. soldiers listening in Portsmouth across the Elizabeth River (and just barely out of sight). The ruse worked, and not a single Confederate soldier was lost as the U.S. authorities abandoned the area and retreated to Fort Monroe across Hampton Roads. After this, Mahone accepted a commission as lieutenant colonel and later colonel of the 6th Virginia Infantry Regiment, and remained in Norfolk, which was now under the command of Benjamin Huger. Mahone was subsequently promoted to brigadier general on November 16, 1861, and commanded the Confederate's Norfolk district until its evacuation the following year.

In May 1862, after Confederate forces fled Norfolk during the Peninsula Campaign, Mahone aided in the construction of the defenses of Richmond on the James River around Drewry's Bluff.[14] A short time later, he led his brigade at the Battle of Seven Pines,[14] and the Battle of Malvern Hill. After the defense of Richmond, Mahone's brigade was assigned from Huger's division to the division of Richard H. Anderson and fought at the Second Battle of Bull Run, where Mahone was shot in the chest while leading his brigade in a charge across Chinn Ridge. Short (5 feet 6 inches (168 cm)) and weighing only 100 pounds (45 kg), he was nicknamed "Little Billy". As one of his soldiers put it, "He was every inch a soldier, though there were not many inches of him." Otelia Mahone worked in Richmond as a nurse when Virginia Governor John Letcher sent word that Mahone had been injured at Second Bull Run, but had only received a "flesh wound". She is said to have replied, "Now I know it is serious for William has no flesh whatsoever." The wound was not life-threatening, but Mahone missed the Maryland Campaign the following month. After two months of recovery, he returned to command, not seeing any significant action at the Battle of Fredericksburg. Mahone used his considerable political skills to lobby for a promotion to major general during the winter of 1862–63. Although several of his fellow officers in the Army of Northern Virginia agreed, Robert E. Lee argued that there was no available position for a major general just then, and Mahone would have to wait until one opened up.

Mahone's brigade was one of the portions of the First Corps that remained with the main army for the Battle of Chancellorsville. After Lee reorganized the army in May 1863, Mahone ended up in the newly created Third Corps of A. P. Hill. At the Battle of Gettysburg, Mahone's brigade was mostly unengaged and suffered only a handful of casualties the entire battle. Mahone was supposed to participate in the attack on Cemetery Ridge on July 2, but against orders, held his brigade back. During Pickett's Charge the following day, Mahone's brigade was assigned to protect artillery batteries and was uninvolved in the main fighting. Mahone's official report for the battle was only 100 words long and gave little insight into his actions on July 2. However, he told fellow brigadier Carnot Posey that division commander Richard H. Anderson had ordered him to stay put. Despite his failure to move his command into action, Mahone suffered no punishment due to his seniority and the fact that he would ultimately become one of a handful of officers in the Army of Northern Virginia to lead a brigade for an entire year's duration.

Although his wound at Manassas had not been severe, Mahone experienced acute dyspepsia all of his life. A cow and chickens accompanied him during the war to provide dairy products. Otelia and their children moved to Petersburg to be near him during the war's final campaign in 1864-65 as Grant moved against Petersburg, seeking to sever the rail lines supplying the Confederate capital of Richmond.

During the Battle of the Wilderness, Mahone's soldiers accidentally wounded James Longstreet. Richard Anderson was appointed to corps command. Mahone took command of Anderson's division, which he led for the remainder of the war, starting at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House. He became widely regarded as the hero of the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864. There, U.S. Army coal miners tunneled under the Confederate line. They blew it up in a massive explosion, killing and wounding many Confederates and breaching a critical point in the defense line around Petersburg. Nevertheless, Mahone rallied the remaining nearby Confederate forces, repelling the attack, and the U.S. soldiers lost their initial advantage. Having begun as an innovative tactic, the Battle of the Crater became a terrible loss for the United States. Mahone's quick and effective action was a rare cause for celebration by the occupants of Petersburg, embattled citizens, and weary troops alike. On July 30, he was promoted to major general.[15]

However, in early April 1865, Grant's strategy at Petersburg eventually succeeded in severing the last rail line from the southern states to supply Petersburg (and hence Richmond). At the Battle of Sailor's Creek on April 6, Lee exclaimed in front of Mahone, "My God, has the army dissolved?" to which he replied, "No, General, here are troops ready to do their duty." Touched by the loyalty of his men, Lee told Mahone, "Yes, there are still some true men left ... Will you please keep those people back?"[16] Mahone was also with Lee at the surrender at Appomattox Court House three days later.

Return to railroading

After the war, Lee advised his generals to return to work rebuilding the southern states' economies. William Mahone did just that and became the driving force in the linkage of N&P, South Side Railroad, and the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad. He was president of all three by the end of 1867.[17] During the post-war Reconstruction period, he worked diligently lobbying the Virginia General Assembly to gain the legislation necessary to form the Atlantic, Mississippi & Ohio Railroad (AM&O), a new line comprising the three railroads he headed, extending 408 miles from Norfolk to Bristol, Virginia, in 1870.[18] This conflicted with the expansion of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad from Baltimore and Alexandria, Virginia. The Mahones were colorful characters: the letters A, M & O were said to stand for "All Mine and Otelia's".[7] They lived in Lynchburg, Virginia, during this time, but moved back to Petersburg in 1872.

The Panic of 1873 put the A, M & O into conflict with its bondholders in England and Scotland. After several years of operating under receiverships, Mahone's relationship with the creditors soured, and an alternate receiver, Henry Fink, was appointed to oversee the A, M & O's finances. Mahone still worked to regain control. His role as a railroad builder ended in 1881, when Philadelphia-based interests outbid him and purchased the A, M & O at auction, renaming it Norfolk and Western (N&W).

Before the Civil War, the Virginia Board of Public Works had invested state funds in a substantial portion of the stock of the A, M & O's predecessor railroads. Although he lost control of the railroad, as a significant political leader in Virginia, Mahone was able to arrange for a portion of the state's proceeds of the sale to be directed to help found a school to prepare teachers to help educate black children and formerly enslaved people near his home at Petersburg, where he had earlier been mayor. The Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute eventually expanded to become Virginia State University, with Virginia native John Mercer Langston returning from Ohio to become its first president. Mahone also directed some funds to help found the predecessor of today's Central State Hospital in Dinwiddie County, also near Petersburg. Mahone personally retained his ownership of land investments which were linked to the N&W's development of the rich coal fields of western Virginia and southern West Virginia, contributing to his rank as one of Virginia's wealthiest men at his death, according to his biographer, author Nelson Blake.

Political career

Mahone was active in Virginia's economic and political life for almost 30 years, beginning amid the Civil War when he was elected to the Virginia General Assembly as a delegate from Norfolk in 1863. He later served as mayor of Petersburg. After his unsuccessful bid for governor in 1877, he became the leader of the Readjuster Party, a coalition of Democrats, Republicans, and African-Americans seeking a reduction in Virginia's prewar debt, and an appropriate allocation made to the former portion of the state that constituted the new State of West Virginia.[19] In 1881, Mahone led the successful effort to elect the readjuster candidate William E. Cameron as the next governor, and he became a United States Senator.[20]

The Readjuster Party did more than refinance the Commonwealth's debts. The party invested heavily in schools, especially for African Americans, and appointed African American teachers for such schools. The party increased funding for what is now Virginia Tech and established its black counterpart, Virginia State. The Readjuster Party abolished the poll tax and the public whipping post. Because of expanded voting, Danville elected a black-majority town council and hired an unprecedented integrated police force.[21]

With the Senate split 37–37 between Republicans and Democrats, Mahone and another third-party candidate willing to caucus with the latter had political influence. Under Senate rules, Vice President of the United States Chester A. Arthur, a Republican, would cast any tie-breaking votes. Mahone bargained for significant concessions before he decided to caucus. Despite being a first-year senator, he became chair of the influential Agriculture Committee. He gained control over Virginia's federal patronage from President James A. Garfield and by the right to select both the Senate's Secretary and Sergeant at Arms.[22]

However, Mahone still faced opposition from the Conservative Party of Virginia, which aligned with the Democrats and grew even more powerful after the 1884 election, when Democrat Grover Cleveland was elected president (with its patronage perks). Mahone maintained his Republican Party affiliation, leading Virginia delegations to the Republican National Conventions of 1884 and 1888. However, he lost his Senate seat to Conservative Democrat John W. Daniel in 1886.[23]

In 1889, Mahone ran for governor on a Republican ticket but lost to Democrat Philip W. McKinney.[24] It was to be 80 more years before Virginia sent another non-Democrat to the Governor's Mansion (Republican A. Linwood Holton Jr., in 1969).

Death

Although out of office, Mahone continued to stay involved in Virginia-related politics until he suffered a catastrophic stroke in Washington, D.C., in the fall of 1895. He died a week later, at 68. His widow, Otelia, lived in Petersburg until her death in 1911.

Legacy

Although Mahone was not to live to see the outcome, Virginia and West Virginia disputed the new state's share of the Virginia government's debt for several decades. The issue was finally settled in 1915 when the United States Supreme Court ruled that West Virginia owed Virginia $12,393,929.50 (~$261 million in 2022). The final installment of this sum was paid off in 1939.

He was interred in the family mausoleum in Blandford Cemetery in Petersburg, Virginia.[25] His widow was interred alongside him. His well-known monogram identifies the mausoleum, an initial "M" centered on a star inside a shield.

Their first home in Petersburg, originally occupied by John Dodson, Petersburg's mayor in 1851–2, was on South Sycamore Street. That structure is now part of the Petersburg Public Library. In 1874, they acquired and greatly enlarged a home on South Market Street, their primary residence after that. Virginia State University, which he helped found as a normal school, is a major community presence nearby.

A large portion of U.S. Highway 460 in eastern Virginia (between Petersburg and Suffolk) parallels the 52-mile (84 km) tangent railroad tracks that Mahone had engineered, passing through some of the towns that the two are believed to have named. Several road sections are labeled "General Mahone Boulevard" and "General Mahone Highway" in his honor. The Route 35 overpass of Route 58 in his native Southampton County, Virginia is named "The General William Mahone Memorial Bridge".

A monument to Mahone's Brigade is on the Gettysburg Battlefield.

The site of the Battle of the Crater is a major feature of the National Park Service's Petersburg National Battlefield Park. In 1927, the United Daughters of the Confederacy erected an imposing monument to his memory. It stands on the preserved Crater Battlefield, a short distance from the Crater itself. The monument states:

To the memory of William Mahone, Major General, CSA, a distinguished Confederate Commander, whose valor and strategy at the Battle of the Crater, July 30, 1864, won for himself and his gallant brigade undying fame.

See also

Notes

- ↑ (2011, January 1). Readjuster Party political party, United States. Britannica. Retrieved October 17, 2023, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Readjuster-Party

- ↑ Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Staff (March 1979). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Brown's Ferry" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

- ↑ 1850 U.S. Federal Census - Slave Schedules, Virginia, Southampton, Nottaway Parish, p. 19

- ↑ Harwood Paige Watkinson Jr., Simone A. Kiere (July 2007). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Mahone's Tavern" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

- ↑ Blake, p. 13

- ↑ Blake, p. 19

- 1 2 3 "Mahone, William (1826–1895)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 2010-11-27.

- ↑ Blake, p. 22

- ↑ Blake, p. 26

- ↑ American Railroad Journal. J.H. Schultz. 1853. p. 752.

- 1 2 Blake, p. 33

- ↑ Blake, p. 35

- ↑ John G. Zehmer and Donald S. B. Hall (April 1999). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Judge Henry Wood Jr. House" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

- 1 2 Blake, p. 43

- ↑ Blake, p. 55

- ↑ Freeman, vol. 3., p. 711.

- ↑ Blake, p. 85

- ↑ Blake, p. 111

- ↑ Blake, p. 154

- ↑ "William Mahone". Lva.virginia.gov. Retrieved 2010-11-27.

- ↑ "Erased from History". Editorial Board. Roanoke Times. October 21, 2017. Page 8.

- ↑ MAHONE, William - Biographical Information

- ↑ Blake, p. 235

- ↑ "William Mahone | American businessman and Confederate general". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-01-03.

- ↑ "MAHONE, William - Biographical Information". bioguide.congress.gov. Retrieved 2018-01-03.

References

- Blake, Nelson Morehouse (1935). William Mahone of Virginia : soldier and political insurgent. Richmond : Garret & Massie.

- Evans, Clement A., Confederate Military History, Vol. III (biography of William Mahone)', 1899.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Striplin, E. F. Pat., The Norfolk & Western: a history Norfolk and Western Railway Co., 1981, ISBN 0-9633254-6-9.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

External links

- Official Website for Mahone's Tavern & Museum including the History of William Mahone

- Map of Norfolk & Petersburg Rail Road, issued by William Mahone

- The New Method of Voting by William Mahone, The North American review. Volume 149, Issue 397, December 1889.

- [https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/Presidents_Death_Eases_Senate_Deadlock.htm Conversion from Readjuster to Republican

- Luebke, P. C. William Mahone (1826–1895). In Encyclopedia Virginia.