The Pětka, or Committee of Five, was an unofficial informal extraparliamentary semi-constitutional political forum that was designed to cope with political difficulties of the First Republic of Czechoslovakia. Founded in September 1920, it was a council of leaders of the coalition parties that made up the Czechoslovak government. Its name came from the Czech word for "five" and is pronounced pyetka. It played a crucial role in the country's politics.

Establishment

.jpg.webp) |  |  |  |  |

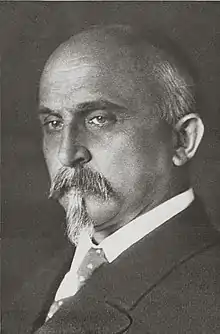

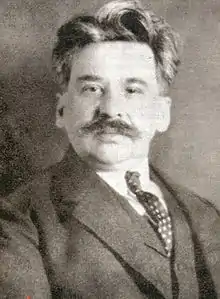

| Rudolf Bechyně (ČSSD) | Alois Rašín (ČsND) | Jan Šrámek (ČSL) | Antonín Švehla (RSZML) | Jiří Stříbrný (ČSNS) |

The Pětka was founded in 1920 to provide guidance to the weak cabinet of Jan Černý, which is said to have "resembled a ventriloquist’s dummy: it had no political will or voice of its own".[1] When the Petka was formed, Czechoslovakia was recovering from the First World War and dealing with the problems it faced as a new state in postwar Europe. The first President of Czechoslovakia, Tomáš Masaryk, saw the new Europe as "a laboratory built over the graveyard of the world war, a laboratory that needs the work of all".[2] In this post-war Europe, Masaryk "recognised that his people still lacked the necessary experience and forbearance necessary for parliamentary government"[3] and knew that a nontraditional political institution would be needed to maintain control. To govern Czechoslovakia it would have been easier for Masaryk to rule as a dictator, but that was against his democratic ideals. Instead, he acted boldly, if not constitutionally, and formed a government of experts, the Petka, in September 1920. In his autobiography, Masaryk stated how anxious he was "to ensure the expert elements of the administration and Government".[4]

The five representative experts and their political parties were Antonín Švehla (Agrarian Party), Alois Rašín (National Democratic Party), Rudolf Bechyně (Social Democratic Party), Jiří Stříbrný (Socialist Party) and Jan Šrámek (People's Party). The main force behind the Petka was Antonín Švehla, served as Czechoslovakia’s prime minister from 1922 to 1926 and from 1926 to 1929 and wielded much influence over the government.

Created in 1920, by the leader of the Agrarian Party, Švehla, it was originally designed as a means to stave off a potential crisis that seemed to be brewing on account of the inability of the leading parties in parliament to form a governing coalition. Invited to participate in the Pětka were the leaders of the four other leading political parties in the newly-formed Republic of Czechoslovakia.

Aims

The Pětka was designed to make up for the lack of "political voice" of the Černý cabinet. The leaders of the five main political parties met at regular intervals to provide direction to the cabinet and advise the prime minister.[5] Each of the five members worked on the principle of "We have agreed that we will agree".[5] The Petka ensured all major disputes took place out of the public eye, and the government maintained a united front for public consumption.[6] The rigid party discipline that characterised the Czechoslovak political system enabled the Petka representatives to control each of their party's members in the Assembly and so they were in a position to control the cabinet.[7] In fact, the Petka has been described as "the real government of the country".[5]

Conceived on an ad hoc basis, the behind-the-scenes forum proved so effective that the leaders of the five parties (the Agrarians, the National Socialists, the National Democrats, the Social Democrats and the Catholic Party) reconvened the Pětka on several occasions for the following two decades.

However, whatever the true dimensions of its power, it is certain that the non-elected rather-shadowy Pětka wielded a great deal of power during the interwar period. In September 1921, it seems to have been the Pětka that was responsible for deciding to install Edvard Beneš as the prime minister. A year later, after Beneš resigned, the Pětka chose Svehla to serve as his successor. As the 1920s progressed, and Czechoslovakia remained relatively stable, the importance of the early Pětka began to wane or rather was incorporated into the cabinet.

Achievements

The Pětka helped keep under control the economic crisis that sparked hyperinflation across Europe between 1922 and 1923. In 1924, it directed the National Assembly to pass a National Insurance Law, which created a social welfare system that was described as being one of the most progressive in the world at the time.[8] The stability of the First Republic of Czechoslovakia regime was maintained, which must be attributed, at least in part, to the Pětka since it followed a moderate course that was acceptable to a majority of the Chamber of Deputies, which prevented a cabinet crisis at times of social unrest. The Pětka provided discipline to the National Assembly and enabled it to reach compromises and to ensure the stability of Czechoslovakia.

Czechoslovakia stood out among other Central and Eastern European countries during the interwar period by its stability. Many other countries in the region fell under dictatorships, experienced prolonged instability or fell under the control of parties on the extreme left or the extreme right.

During the interwar period in Czechoslovakia, the left never dominated a cabinet, the communists never participated in a government and the coalition was never faced with an organised opposition bloc of opponent parties that was capable of assuming office itself. The Pětka's existence enabled Czechoslovakia to be described as being "internally stable and externally respected".[9]

The establishment and effectiveness of the Pětka reflects two significant aspects of political life in the country after the First World War. Firstly, it demonstrates the impulse towards consensus among the leaders of the newly formed-Czechoslovakia, which had come into being as an independent state only by the collapse of Austria-Hungary at the end of the war. That sentiment was captured in the slogan of the coalitions forged by Švehla: "We have agreed that we will agree". Whatever their differences and personal leaders, the Czechoslovak leaders felt obliged to search out common ground to prevent the country from falling into chaos. Secondly, the presence and the power of the Pětka demonstrates the fragility and the immaturity of Czechoslovakian democracy.

The legacy of the Pětka is rather mixed. On one hand, it seems to have played an important role in some of the most significant accomplishments of the short-lived First Republic. It can be given credit, among other things, for the vast majority of social reforms enacted between 1918 and 1923. The eight-hour workday, sickness and unemployment relief and restrictions on female and child labour were some of the reforms that the Pětka supposedly engineered. In comparison with the other countries carved out of the remnants of Austria-Hungary, Czechoslovakia was a prosperous and secure haven. Some credit must go to the Pětka.

On the other hand, it can be argued that the reliance on the Pětka and on backroom negotiations left the country ill-prepared when the difficulties it encountered defied compromise. Specifically, the leaders found it impossible to contend with the threat posed by the rise of Nazism in Germany and the various repercussions that it had on life in Czechoslovakia, with its large and increasingly-hostile German minority.

Criticisms

The Pětka faced criticism for being unconstitutional and undemocratic. Even Masaryk himself acknowledged the Pětka was not entirely democratic and said in a 1925 speech:

"I am a convinced democrat and I accept the inherent difficulties of democracy. Our difficulties arise from the high demands of democracy, which requires a body of citizens who are truly educated in the political sense, and an intelligent electorate, both men and women. Hence I am not in favour of government by experts or officials. Of course we have already had two Cabinets of Officials (the Petka). What does that signify? It means that for us the transition from monarchism to democracy is a difficult one. Problems, however, are solved by people who think and possess knowledge, and are not merely elected".[3]

End

When it was founded, it was thought the Petka would last only briefly. However, "the provisional often proves lasting",[1] and it lasted in some form or another until the end of the First Republic of Czechoslovakia. With the dissolution of the Pětka came the end of discipline in the coalition. Czech and Slovak politicians began to argue, and long-suppressed conflicts were soon exposed.

See also

References

- 1 2 Mamatey (1973), p. 108

- ↑ Masaryk (1935), p. 299

- 1 2 Cohen (1941), p. 237

- ↑ Masaryk (1935), p. 292

- 1 2 3 Crampton (1997), p. 63

- ↑ "Czechoslovakia". GeoWorld History: Europe to Eurasia. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007.

- ↑ Diamond (1947), p. 24

- ↑ Mamatey (1973), p. 127

- ↑ Mamatey (1973), p. 240

Sources

- Mamatey, Victor S. (1973). "The Development of Czechoslovak Democracy, 1920-1938". In Victor S. Mamatey; Radomir Luza (eds.). A History of the Czechoslovak Republic, 1918-1948. Princeton University Press.

- Masaryk, Tomáš Garrigue (1935). President Masaryk Tells His Story. Translated by Karel Čapek. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- Cohen, Victor (1941). The Life and Times of Masaryk. London: John Murray Albemarle Street.

- Crampton, R. J. (1997). Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century – And After. New York: Routledge.

- Diamond, William (1947). Czechoslovakia Between East and West. London: Stevens & Sons Limited.