| RPG-7 | |

|---|---|

An RPG-7 launcher (top) with a Bulgarian PG-7G inert training warhead and booster (bottom) | |

| Type | Handheld rocket launcher[1] |

| Place of origin | Soviet Union |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1961–present |

| Used by | See Users |

| Wars | See Conflicts |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Bazalt |

| Designed | 1958 |

| Manufacturer | Bazalt and Degtyarev plant (Russian Federation) |

| Unit cost | c. US$2500 |

| Produced | 1958–present |

| No. built | 9,000,000+[2] |

| Variants |

|

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 6.3 kg (13.9 lb) (without a telescopic sight) 7 kg (15.4 lb) (with PGO-7) |

| Length | 950 mm (37.4 in) |

| Cartridge | 85 mm (3.3 in) |

| Caliber | 40 mm (1.6 in) |

| Muzzle velocity | 115 m/s (380 ft/s) (boost) 300 m/s (980 ft/s) (flight) |

| Effective firing range | 330 m (1,080 ft) (PG-7V) |

| Maximum firing range | 700 m (2,300 ft) (OG-7V) (self detonates at ~920 m (3,020 ft)) |

| Sights | PGO-7 (2.7×), UP-7V telescopic sight and 1PN51/1PN58 night vision sights Red dot reflex sight |

The RPG-7 (Russian: РПГ-7, Ручной Противотанковый Гранатомёт, romanized: Ruchnoy Protivotankovyy Granatomot, lit. 'Handheld Anti-Tank Grenade-launcher') is a portable, reusable, unguided, shoulder-launched, anti-tank, rocket launcher. The RPG-7 and its predecessor, the RPG-2, were designed by the Soviet Union, and are now manufactured by the Russian company Bazalt. The weapon has the GRAU index (Russian armed forces index) 6G3.

The ruggedness, simplicity, low cost, and effectiveness of the RPG-7 has made it the most widely used anti-armor weapon in the world. Currently around 40 countries use the weapon; it is manufactured in several variants by nine countries. It is popular with irregular and guerrilla forces.

Widely produced, the most commonly seen major variations are the RPG-7D (десантник – desantnik – paratrooper) model, which can be broken into two parts for easier carrying; and the lighter Chinese Type 69 RPG. DIO of Iran manufactures RPG-7s with olive green handguards, H&K pistol grips, and a commando variant.

The RPG-7 was first delivered to the Soviet Army in 1961 and deployed at the squad level. It replaced the RPG-2, having clearly out-performed the intermediate RPG-4 design during testing. The current model produced by the Russian Federation is the RPG-7V2, capable of firing standard and dual high-explosive anti-tank (HEAT) rounds, high explosive/fragmentation, and thermobaric warheads, with a UP-7V sighting device fitted (used in tandem with the standard 2.7× PGO-7 optical sight) to allow the use of extended range ammunition. The RPG-7D3 is the equivalent paratrooper model. Both the RPG-7V2 and RPG-7D3 were adopted by the Russian Ground Forces in 2001.

Description

The launcher is reloadable and based around a steel tube, 40 mm (1.6 in) in diameter, 950 mm (37 in) long, and weighing 7 kg (15 lb). The middle of the tube is wood wrapped to protect the user from heat and the end is flared. Sighting is usually optical with a back-up iron sight, and passive infrared and night sights are also available. The launchers designated RPG-7N1 and RPG-7DN1 can thus mount the multi-purpose night vision scope 1PN51[4] and the launchers designated RPG-7N2 and RPG-7DN2 can mount the multi-purpose night vision scope 1PN58.[5]

As with similar weapons, the grenade protrudes from the launch tubes. It is 40–105 mm (1.6–4.1 in) in diameter and weighs between 2 kg (4.4 lb)[6] and 4.5 kg (9.9 lb). It is launched by a gunpowder booster charge, giving it an initial speed of 115 m/s (380 ft/s), and creating a cloud of light grey-blue smoke that can give away the position of the shooter.[7] The rocket motor[lower-alpha 1] ignites after 10 m (33 ft) and sustains flight out to 500 m (1,600 ft) at a maximum velocity of 295 m/s (970 ft/s). The grenade is stabilized by two sets of fins that deploy in-flight: one large set on the stabilizer pipe to maintain direction and a smaller rear set to induce rotation. The grenade can fly up to 1,100 m (3,600 ft); the fuze sets the maximum range, usually 920 m (3,020 ft).[8]

Propulsion system

According to the United States Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) Bulletin 3u (1977) Soviet RPG-7 Antitank Grenade Launcher—Capabilities and Countermeasures, the RPG-7 munition has two sections: a "booster" section and a "warhead and sustainer motor" section. These must be assembled into the ready-to-use grenade. The booster consists of a "small strip powder charge" that serves to propel the grenade out of the launcher; the sustainer motor then ignites and propels the grenade for the next few seconds, giving it a top speed of 294 m/s (960 ft/s). The TRADOC bulletin provides anecdotal commentary that the RPG-7 has been fired from within buildings, which agrees with the two-stage design. It is stated that only a 2 metres (6.6 feet) standoff to a rear obstruction is needed for use inside rooms or fortifications. The fins not only provide drag stabilization, but are designed to impart a slow rotation to the grenade.

Due to the configuration of the RPG-7 sustainer/warhead section, it responds counter-intuitively to crosswinds. A crosswind will tend to exert pressure on the stabilizing fins, causing the projectile to turn into the wind (see Weathervane effect). While the rocket motor is still burning, this will cause the flight path to curve into the wind. The TRADOC bulletin explains aiming difficulties for more distant moving targets in crosswinds at some length.

Ammunition

I) The head contains

- trigger

- conductive cone

- aerodynamic fairing

- conical liner

- body

- explosive

- conductor

- detonator

- nozzle block

- nozzle

- motor body

- propellant

- motor rear

- ignition primer

- fin

- cartridge

- charge

- turbine

- tracer

- foam wad

The RPG-7 can fire a variety of warheads for anti-armor (HEAT, PG-Protivotankovaya Granata) or anti-personnel (HE, OG-Oskolochnaya Granata) purposes, usually fitting with an impact (PIBD) and a 4.5 second fuze. Armor penetration is warhead dependent and ranges from 300–600 mm (12–24 in) of RHA; one warhead, the PG-7VR, is a 'tandem charge' device, used to defeat reactive armor with a single shot. The Russian Ministry of Defense said in December 2023 that it has modified the RPG-7V grenade launcher in order to shoot 82-mm mines.[9]

Current production ammunition for the RPG-7V2 consists of four main types:

- PG-7VL [c.1977] – improved 93 mm (3.7 in) HEAT warhead effective against most vehicles and fortified targets.[6]

- PG-7VR [c.1988] – tandem charge warhead designed to penetrate up to 750 mm (30 in) rolled homogeneous armour equivalence of explosive reactive armor and the conventional armor underneath. It has a range of 200 m (660 ft).[10]

- TBG-7V Tanin [c.1988] – 105 mm (4.1 in) thermobaric warhead for anti-personnel and urban warfare.

- OG-7V [c.1999] – 40 mm (1.6 in) fragmentation warhead for anti-personnel warfare. Has no sustainer motor.

Other warhead variants include:

- PG-7V [c.1961] – baseline 85 mm (3.3 in) HEAT warhead capable of penetrating 260 mm (10 in) RHA.[11]

- PG-7VM [c.1969] – improved 70 mm (2.8 in) HEAT warhead capable of penetrating 300 mm (12 in) RHA.

- PG-7VS [c.1972] – improved 73 mm (2.9 in) HEAT warhead capable of penetrating 400 mm (16 in) RHA.

- PG-7VS1 [c.mid-1970s] – cheaper PG-7VS version capable of penetrating 360 mm (14 in) RHA.

- GSh-7VT [c.2013] – anti-bunker warhead with cylindrical follow-through blast-fragmentation munition followed by explosively formed penetrator.[12]

- OGi-7MA [unknown] – anti-personnel fragmentation munition developed for the Bulgarian ATGL-L. improved equivalent to the Soviet OG-7V. Compatible with RPG-7.[13]

Specifications

Manufacturer specifications for the RPG-7V1.[14]

| Name | Type | Image | Weight | Explosive weight[15][16] | Diameter | Penetration | Lethal radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PG-7VL | Single-stage HEAT | 2.6 kg (5.7 lb) | 730 g (26 oz) OKFOL (95% HMX + 5% wax) | 93 mm (3.7 in) | >500 mm (20 in) RHA | ||

| PG-7VR | Tandem charge HEAT | 4.5 kg (9.9 lb) | 1.43 kg (3.2 lb) OKFOL (95% HMX + 5% wax) | 64 mm (2.5 in)/105 mm (4.1 in) | 600 mm (24 in) RHA (with reactive armor) 750 mm (30 in) RHA (without reactive armor) |

||

| OG-7V | Fragmentation | 2 kg (4 lb) | 210 g (7.4 oz) A-IX-1 | 40 mm (1.6 in) | 7 m (23 ft) (vs. body armor)[17][18] | ||

| TBG-7V | Thermobaric | 4.5 kg (9.9 lb) | 1.9 kg (4.2 lb) ОМ 100МИ-3Л + 0.25 kg (0.55 lb) A-IX-1 (as thermobaric explosive booster) | 105 mm (4.1 in) | 10 m (30 ft) |

Hit probabilities

| Range m (ft) | Percent |

|---|---|

| 50 (160) | 100 |

| 100 (330) | 96 |

| 200 (660) | 51 |

| 300 (980) | 22 |

| 400 (1,300) | 9 |

| 500 (1,600) | 4 |

A 1976 U.S. Army evaluation of the weapon gave the hit probabilities on a 5-by-2.5-metre (16.4 ft × 8.2 ft) panel moving sideways at 4 m/s (13 ft/s).[19] Crosswinds cause additional issues as the round steers into the wind; in an 11 km/h (6.8 mph) wind, firing at a stationary tank sized target, the gunner cannot expect to get a first-round hit more than 50% of the time at 180 m (590 ft).[20]

History of use

The RPG-7 was first used in 1967 by Egypt during the Six-Day War, and by the Viet Cong during the Vietnam War, but it did not see widespread usage in Vietnam until the following year.[21]

The RPG-7 was used by the Provisional Irish Republican Army in Northern Ireland from 1969 to 2005, most notably in Lurgan, County Armagh, where it was used against British Army observation posts and the towering military base at Kitchen Hill in the town.[22] The IRA also used them in Catholic areas of West Belfast against British Army armoured personnel carriers and Army forward operating bases (FOB). Beechmount Avenue in Belfast became known as "RPG Avenue" after attacks on British troops.[23]

In Mogadishu, Somalia, RPG-7s were used to down two U.S. Army Black Hawk helicopters in 1993.[24][25]

During the first and second Chechen wars, Chechens used RPG-7 which they had captured from Soviet bases and used them against Russian armored columns. During the first war, Russians may have lost 100 tanks and 250 AFVs in Grozny.[26] The Chechens were able to knock out T-72s with three or four RPG-7 hits. Against T-72s with explosive reactive armor, the Chechens fired an RPG in close range (within 50 m (160 ft)) to detonate the armor and then followed this with RPG hits on the now exposed point of the tank, also from close range.[27] The RPG-7 was also effective against armoured fighting vehicles (AFVs), buildings and personnel.[28]

The PG-7VR has been used by Iraqi insurgents.[29] On 28 August 2003, it achieved a mobility kill against an American M1 Abrams hitting the left side hull next to the forward section of the engine compartment.[30]

During the War in Afghanistan (2001–2021), several M1A2 Abrams were temporarily disabled by RPG-7 hits.[31]

Users

Afghanistan[32]

Afghanistan[32] Algeria[32]

Algeria[32] Angola[32]

Angola[32] Armenia[32]

Armenia[32]

Azerbaijan[32]

Azerbaijan[32] Bangladesh: Chinese Type 69 RPG variant used by Bangladesh Army.[34]

Bangladesh: Chinese Type 69 RPG variant used by Bangladesh Army.[34] Belarus[32]

Belarus[32] Benin[32]

Benin[32] Botswana[32]

Botswana[32] Bulgaria: Produced locally by Arsenal Corporation as ATGL-L.[35][36]

Bulgaria: Produced locally by Arsenal Corporation as ATGL-L.[35][36] Burkina Faso[37][38]

Burkina Faso[37][38] Cambodia[32]

Cambodia[32] Cape Verde[32]

Cape Verde[32] Central African Republic[32]

Central African Republic[32] Chad[32]

Chad[32] China: Type 69 reverse-engineered copy.[39]

China: Type 69 reverse-engineered copy.[39] Congo-Brazzaville[32]

Congo-Brazzaville[32] Congo-Kinshasa[32]

Congo-Kinshasa[32] Croatia[32]

Croatia[32] Cuba[32]

Cuba[32] Cyprus[32]

Cyprus[32] Czech Republic[32]

Czech Republic[32] Djibouti[32]

Djibouti[32] Egypt:[32] Locally produced without license as PG-7 by the Sakr Factory for Developed Industries.[40]

Egypt:[32] Locally produced without license as PG-7 by the Sakr Factory for Developed Industries.[40] Eritrea[32]

Eritrea[32] Estonia[32]

Estonia[32] Fiji[41]

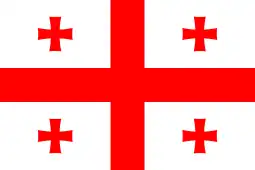

Fiji[41] Georgia: Modified version "RPG-7D" locally produced by STC Delta.[42][43][44]

Georgia: Modified version "RPG-7D" locally produced by STC Delta.[42][43][44] Ghana[32]

Ghana[32] Guinea[32]

Guinea[32] Guyana[32]

Guyana[32] Hungary[45]

Hungary[45] Iran[32] Produced locally as Sageg.[46]

Iran[32] Produced locally as Sageg.[46] Iraq[32] Produced locally as Al-Nassira from the 1980s by Ba'athist Iraq.[46]

Iraq[32] Produced locally as Al-Nassira from the 1980s by Ba'athist Iraq.[46] Israel: Large stocks held as secondary ATW.[21] Rounds produced locally.[47]

Israel: Large stocks held as secondary ATW.[21] Rounds produced locally.[47] Jordan[32]

Jordan[32] Kazakhstan[32]

Kazakhstan[32] Kyrgyzstan[32]

Kyrgyzstan[32] Laos[32]

Laos[32] Latvia[32]

Latvia[32] Lebanon[32]

Lebanon[32] Lesotho[48]

Lesotho[48] Liberia: Used by both the Liberian Army and guerrilla factions in the Liberian Civil War.[31]

Liberia: Used by both the Liberian Army and guerrilla factions in the Liberian Civil War.[31] Libya[32] (used by both sides in the Libyan Civil War)

Libya[32] (used by both sides in the Libyan Civil War) Madagascar[32]

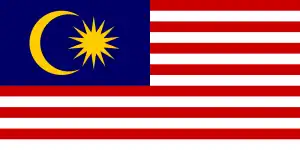

Madagascar[32] Malaysia: Bulgarian ATGL-L versions are purchased and used since the early 2000s[49][50]

Malaysia: Bulgarian ATGL-L versions are purchased and used since the early 2000s[49][50] Mali[51]

Mali[51] Malta[32]

Malta[32] Mauritania[32]

Mauritania[32] Moldova:[32]

Moldova:[32]

Mongolia[32]

Mongolia[32] Morocco[32]

Morocco[32] Mozambique: Non state-users.[52]

Mozambique: Non state-users.[52] Nicaragua[32]

Nicaragua[32] Nigeria: Produced under license by the Defence Industries Corporation of Nigeria[32][53]

Nigeria: Produced under license by the Defence Industries Corporation of Nigeria[32][53] Niger[54]

Niger[54] North Korea[32]

North Korea[32] North Macedonia[32]

North Macedonia[32] Pakistan: Used by the Pakistan Army and paramilitary forces.[32] RPG-7V version made under license by Pakistan Machine Tool Factory.[55][56]

Pakistan: Used by the Pakistan Army and paramilitary forces.[32] RPG-7V version made under license by Pakistan Machine Tool Factory.[55][56] Papua New Guinea[57]

Papua New Guinea[57] Philippines: The army has three different variants: 250 ATGL-L2 from Bulgaria, 30 Type 69 from China, and 744 RPG-7V2 from Russia.[58]

Philippines: The army has three different variants: 250 ATGL-L2 from Bulgaria, 30 Type 69 from China, and 744 RPG-7V2 from Russia.[58] Poland:[32] Produced RPG-7 and RPG-7W variants.[59]

Poland:[32] Produced RPG-7 and RPG-7W variants.[59] Romania:[32] Produced locally by SC Carfil SA from Brașov as AG-7 (Romanian: Aruncătorul de Grenade 7, Grenade Launcher 7).[60]

Romania:[32] Produced locally by SC Carfil SA from Brașov as AG-7 (Romanian: Aruncătorul de Grenade 7, Grenade Launcher 7).[60] Russia[32]

Russia[32] Rwanda[32]

Rwanda[32] Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic: Used by the Polisario Front.[61]

Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic: Used by the Polisario Front.[61] Sao Tome and Principe[32]

Sao Tome and Principe[32] Senegal[32]

Senegal[32] Serbia: Made by PPT Namenska.[62]

Serbia: Made by PPT Namenska.[62] Seychelles[32]

Seychelles[32] Sierra Leone[32]

Sierra Leone[32] Somalia[32]

Somalia[32] South Africa: South African National Defence Force.[63]

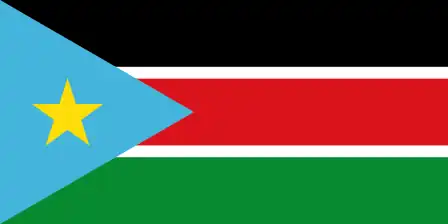

South Africa: South African National Defence Force.[63] South Sudan: South Sudan Democratic Movement, Sudan Liberation Movement/Army, South Sudan Defence Forces, Sudan People's Liberation Army used RPG-7, Type 69s and Iranian-made RPGs.[64]

South Sudan: South Sudan Democratic Movement, Sudan Liberation Movement/Army, South Sudan Defence Forces, Sudan People's Liberation Army used RPG-7, Type 69s and Iranian-made RPGs.[64] Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka Sudan: Made by Military Industry Corporation as the Sinar.[65]

Sudan: Made by Military Industry Corporation as the Sinar.[65] Suriname: Used by the Military of Suriname.[32]

Suriname: Used by the Military of Suriname.[32] Syria[32]

Syria[32] Tajikistan:[32]

Tajikistan:[32] Togo[32]

Togo[32] Turkmenistan:[32]

Turkmenistan:[32] Ukraine:[32]

Ukraine:[32] Uzbekistan:[32] Produced locally.

Uzbekistan:[32] Produced locally. Venezuela[32]

Venezuela[32] Vietnam:[32] Locally produced and designated as RPG7V-VN. Also popularly recognized under the designation B-41.[66]

Vietnam:[32] Locally produced and designated as RPG7V-VN. Also popularly recognized under the designation B-41.[66] Yemen[32]

Yemen[32] Zambia[32]

Zambia[32] Zimbabwe[32]

Zimbabwe[32]

Non-state users

Former users

Conflicts

1960s

- Vietnam War (1955–1975): First used in 1967.[21]

- Six Day War (1967)[21]

1970s

- Yom Kippur War (1973)[71]

- Ethiopian Civil War (1974–1991)

- Angolan Civil War (1975–2002)

- Sino-Vietnamese War (1979)

- Soviet–Afghan War (1979–1989)[72]

1980s

- Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988)

- Sri Lankan Civil War (1983–2009)[73]

- Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005)

1990s

- Gulf War (1990–1991)[74]

- Somali Civil War (1991–present)[74]

- First Chechen War (1994–1996)[26]

- Eritrean–Ethiopian War (1998–2000)

- Second Chechen War (1999–2009)[26]

2000s

- War in Afghanistan (2001–2021)[74]

- Iraq War (2003–2011)[74]

2010s

- Syrian Civil War (2011–present)

- War in Iraq (2013–2017)

- South Sudanese Civil War (2013–2020)

- Yemeni Civil War (2014–present)

2020s

- Tigray War (2020–2022)

- Russian invasion of Ukraine (2022–ongoing)

- War in Amhara (2023–ongoing)

- 2023 Israel–Hamas war (2023-ongoing)

See also

Notes

- ↑ no rocket motors in OG-7V

References

- ↑ "RPG-7/RPG-7V/RPG-7VR Rocket Propelled Grenade Launcher (Multi Purpose Weapon)". Defense Update. 2006. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ↑ Small Arms Survey. Graduate Institute of International Studies. 2004. p. 8.

- ↑ Rottman 2010, p. 41.

- ↑ ИЗДЕЛИЕ 1ПН51 ТЕХНИЧЕСКОЕ ОПИСАНИЕ И ИНСТРУКЦИЯ ПО ЭКСПЛУАТАЦИИ [Product 1PN51 Technical Description and Operating Instructions] (in Russian). January 1992. pp. 11, 16.

- ↑ ИЗДЕЛИЕ 1ПН58 ТЕХНИЧЕСКОЕ ОПИСАНИЕ И ИНСТРУКЦИЯ ПО ЭКСПЛУАТАЦИИ [Product 1PN58 Technical Description and Operating Instructions] (in Russian). February 1991. pp. 5, 15.

- 1 2 "RosOboronExport". rusarm.ru. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ↑ (U.S.), Infantry School; School, United States Army Infantry; Office, United States Army Infantry School Editorial and Pictorial; Dept, United States Army Infantry School Book (3 October 1998). "Infantry". U.S. Army Infantry School – via Google Books.

- ↑ Grillo, Ioan (25 October 2012). "Mexico's Drug Lords Ramp Up Their Arsenals with RPGs". Time. Archived from the original on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2013 – via world.time.com.

- ↑ "ЦАМТО / / Минобороны представило кадры боевой работы гранатометчиков группировки войск «Восток»". ЦАМТО / Центр анализа мировой торговли оружием (in Russian). 25 December 2023. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ↑ "Anti-tank Rocket PG-7VR | Catalog Rosoboronexport".

- ↑ RPG-7 antitank grenade launcher (USSR / Russia) Archived 16 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine – Modernfirearms.net

- ↑ FKP GkNIPAS completes development of anti-bunker round for RPG-7V2 grenade launcher Archived 22 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine – Janes.com, 30 June 2013

- ↑ Bulgarian OGi-7MA rounds were delivered to Bakhmut – mil.in.ua, 26 February 2023

- ↑ "Rosoboronexport". Rusarm.ru. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ↑ Per Ordata Archived 10 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Per Archived 8 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine defense-update RPG-29 due to PG-29V and PG-7VR has same warhead

- ↑ Tilstra, Russel C. (10 January 2014). Small Arms for Urban Combat: A Review. ISBN 9780786488759.

- ↑ "OG-7V Fragmentation round". Rosoboronexport. Rosoboronexport.

- ↑ TRADOC Bulletin 1, Range and Lethality of U.S. and Soviet Anti-Armour Weapons. United States Army Training And Doctrine Command. 30 September 1975. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ↑ TRADOC Bulletin 3, Soviet RPG-7 Antitank Grenade Launcher (PDF). United States Army Training And Doctrine Command. November 1976. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 August 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 Rottman 2010, p. 33.

- ↑ Oppenheimer, A. R. (2009). IRA. The Bombs and the Bullets: A history of deadly ingenuity. Dublin: Irish Academic Press, p. 227. ISBN 978-0-7165-2895-1, pp. 240–241.

- ↑ Harrison, David (13 May 2007). "Fragile calm behind Ulster's 'peace walls'". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ↑ Speck, Shane (11 March 2004). "How Rocket-Propelled Grenades Work". Science.howstuffworks.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ↑ Thornton, Rod (12 February 2007). Asymmetric Warfare: Threat and Response in the 21st Century. Polity. ISBN 9780745633657 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 3 Rottman 2010, p. 64.

- ↑ Rottman 2010, p. 65.

- ↑ Rottman 2010, p. 68.

- ↑ Photo: Mystery Missile Solved

- ↑ Army Times: "'Something' Felled An Abrams Tank In Iraq - But What? Mystery Behind Aug. 28 Incident Puzzles Army Officials"

- 1 2 Rottman 2010, p. 43.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 Jones, Richard D. Jane's Infantry Weapons 2009/2010. Jane's Information Group; 35 edition (27 January 2009). ISBN 978-0-7106-2869-5.

- ↑ Gore, Patrick Wilson (2008). 'Tis Some Poor Fellow's Skull: Post-Soviet Warfare in the Southern Caucasus. iUniverse. p. 60. ISBN 9780595486793. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

RPG-7 karabagh.

- ↑ Small Arms Survey (2011). "Larger but Less Known: Authorized Light Weapons Transfers". Small Arms Survey 2011: States of Security. Oxford University Press. p. 29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2011.

- ↑ "40 mm ATGL-L Family - Arsenal JSCo. - Bulgarian manufacturer of weapons and ammunition since 1878". www.arsenal-bg.com.

- ↑ ATGL-L anti-tank grenade launcher Archived 21 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine, arsenal.bg

- ↑ "Burkina Faso: Un véhicule emporté lors d'un braquage à Ouahigouya". koaci.com (in French). 13 October 2016. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ↑ Cherisey, Erwan de (July 2019). "El batallón de infantería "Badenya" de Burkina Faso en Mali – Noticias Defensa En abierto". Revista Defensa (in Spanish) (495–496).

- ↑ Rottman 2010, p. 36.

- ↑ Rottman 2010, p. 37.

- ↑ "Rosyjska broń dla Fidżi" (in Polish). altair.pl. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ↑ "Anti-tank rocket-propelled grenade launcher RPG-7G". Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ↑ "ქართული წარმოების სამხედრო აღჭურვილობა". geo-army.ge. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ↑ "RPGL-7D : Versatile, Cost Effective, Lethal" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ↑ Lugosi, József (2008). "Gyalogsági fegyverek 1868–2008". In Lugosi, József; Markó, György (eds.). Hazánk dicsőségére: 160 éves a Magyar Honvédség. Budapest: Zrínyi Kiadó. p. 389. ISBN 978-963-327-461-3.

- 1 2 Rottman 2010, p. 38.

- ↑ Katz, Samuel (1986) Israeli Defence Forces Since 1973. Osprey ISBN 0-85045-687-8

- ↑ Berman, Eric G. (March 2019). Beyond Blue Helmets: Promoting Weapons and Ammunition Management in Non-UN Peace Operations (PDF). Small Arms Survey/MPOME. p. 43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2019.

- ↑ Nazrini Badarun (24 May 2017). "Unit khas polis ESSZONE akan terima RPG baru" (in Malay). New Sabah Times. Archived from the original on 5 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ↑ "Rocket-propelled grenade boost for security". Daily Express. 24 May 2017. Archived from the original on 5 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ↑ Touchard, Laurent (18 June 2013). "Armée malienne : le difficile inventaire". Jeune Afrique. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ↑ Vines, Alex (March 1998). "Disarmament in Mozambique". Journal of Southern African Studies. 24 (1): 191–205. doi:10.1080/03057079808708572. JSTOR 2637453.

- ↑ Okoroafor, Cynthia (27 August 2015). "You probably didn't know that Nigeria already manufactures these weapons". Ventures. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ↑ "Bundeswehr in Niger: Unterwegs mit einer Patrouille". www.bmvg.de. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ↑ "IDEAS 2012". 6 (3). Small Arms Defense Journal. 5 December 2014. Archived from the original on 2 June 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "IDEAS 2016—Pakistan". 9 (4). Small Arms Defense Journal. 13 October 2017. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Alpers, Philip (2010). Karp, Aaron (ed.). The Politics of Destroying Surplus Small Arms: Inconspicuous Disarmament. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge Books. pp. 168–169. ISBN 978-0-415-49461-8.

- ↑ "Philippines starts transition to RPG-7 infantry rocket launchers". Asia Pacific Defense Journal. 31 January 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ↑ Rottman 2010, p. 39.

- ↑ "Carfil website". Archived from the original on 27 August 2007.

- ↑ Ignacio Fuente Cobo; Fernando M. Mariño Menéndez (2006). El conflicto del Sahara occidental (PDF) (in Spanish). Ministerio de Defensa de España & Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. p. 78. ISBN 84-9781-253-0.

- ↑ "Rbr7 - PPT NAMENSKA". www.ppt-namenska.rs. Archived from the original on 1 November 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ↑ "Anti Tank weapons". South African Army. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ↑ Small Arms Survey (2014). "Weapons tracing in Sudan and South Sudan" (PDF). Small Arms Survey 2014: Women and guns (PDF). Cambridge University Press. pp. 227, 229, 234. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ↑ Sinar Light Antitank Rocket Launcher Archived 1 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 17 March 2009.

- ↑ Rottman 2010, p. 19.

- ↑ "After decades in combat, Russia's RPG is as dangerous and popular as ever". Insider. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Still a Killer: Why Russia's Old RPG-7 Rocket Launcher Lives On". The National Interest. 17 April 2021. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ↑ "Houthis". United Against Nuclear Iran. Archived from the original on 4 April 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- 1 2 "For some, the RPG-7 was once icon of 'armed struggle' - now it's a symbol of its futility". Belfasttelegraph. Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ↑ Rottman 2010, p. 62.

- ↑ Rottman 2010, p. 63.

- ↑ "LTTE's Rare Infantry Weapons". srilankaguardian.org. 17 November 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Rottman 2010, p. 70.

Bibliography

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2010). The Rocket Propelled Grenade. Weapon 2. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-153-5.