The Pacification of Tonkin (1886–1896) was a slow and ultimately successful military and political campaign undertaken by the French Empire in the northern portion of Tonkin (modern-day north Vietnam) to reestablish order in the wake of the Tonkin campaign (1883 1886), to entrench a French protectorate in Tonkin, and to suppress Vietnamese anti-French uprising.

Background

Following their conquest of Cochinchina (southern Vietnam) in the 1860s, the French attempted to extend their influence into Tonkin (northern Vietnam). A first, abortive attempt to intervene in Tonkin was made by Francis Garnier in 1873. Nine years later, in April 1882, Henri Rivière seized the citadel of Hanoi, inaugurating the second French intervention. Although Rivière's career ended in disaster a year later, with his defeat and death at the hands of the Black Flag Army at the Battle of Paper Bridge (19 May 1883), Jules Ferry's expansionist government in France sent strong reinforcements to Tonkin to avenge this defeat. Although it would take many years before Tonkin was truly pacified, the second French attempt to subdue Tonkin was ultimately successful.

In August 1883, in the wake of Admiral Amédée Courbet's victory at the Battle of Thuận An, the Vietnamese court at Huế was forced to recognise a French protectorate over both Annam (French protectorate) and Tonkin.[1] Efforts by the French to entrench their protectorate in Tonkin were complicated by the outbreak of the Sino-French War in August 1884, which tied down large French forces around Hưng Hóa and Lạng Sơn, and later by the Cần Vương uprising in southern Vietnam in July 1885, which required the diversion of French forces from Tonkin to Annam. When the Sino-French War ended in April 1885, there were 35,000 French troops in Tonkin, but the area of French control was restricted to the Red River Delta. Between April 1885 and April 1886 French troops closed up to the Chinese border, raising the tricolour and establishing customs posts at Lào Cai and other frontier crossings into Yunnan and Guangxi provinces, but large swathes of Tonkinese territory remained under the control of insurgent groups.

The Tonkin campaign, a struggle by France since June 1883 against various opponents, including Vietnamese forces under the command of Prince Hoàng Kế Viêm, Liu Yongfu's Black Flag Army, and finally the Chinese Yunnan and Guangxi Armies, officially came to an end in early 1886. On the recommendation of General Charles-Auguste-Louis Warnet (1828–1913), the commander-in-chief of the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps, Tonkin was declared 'pacified' in April 1886, and this achievement was symbolised by the formal downgrading of the expeditionary corps into a division of occupation under the command of General Ferdinand Jamont. This declaration, made for domestic consumption in France, where opposition to French adventures in Tonkin was growing, was purely cosmetic, and concealed the reality of a continuing, low-level insurgency in Tonkin.[2]

Character of the Tonkin insurgency

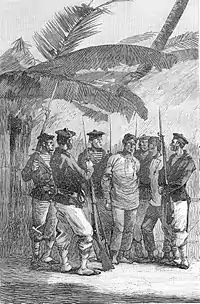

The Cần Vương insurgency against the French launched in Annam in July 1885 after Hàm Nghi's flight from Huế was portrayed by the insurgents as a patriotic, anti-French, struggle to 'aid the king'. The insurgency in Tonkin was rather more complex. Many of the insurgents fought for patriotic motives, but others simply wanted to exploit the anarchy that prevailed in much of Tonkin at the end of the Sino-French War. The Chinese armies that had fought the Sino-French War dutifully withdrew from Tonkin in May and June 1885, but their ranks were by then full of Vietnamese volunteers or conscripts, and these men, unpaid for months, were simply disbanded on Tonkinese soil and left to fend for themselves. They kept their weapons and supported themselves by brigandage, in many cases sheltering behind the patriotic rhetoric of the Cần Vương insurgency. The French, although reluctant to admit that any of the 'brigands', 'bandits' and 'pirates' in arms against them had noble motives, were well aware that they were fighting a range of enemies in Tonkin:

The reign of the mandarins was now ended, but...the Black Flags and the other professional brigands who had been fighting us were swollen by discharged Chinese soldiers, other soldiers who had deserted with their arms and equipment because they had not been paid, Annamese ne’er-do-wells who preferred pillage to agriculture, and sometimes law-abiding peasants who had been forcibly conscripted.[3]

Liu Yongfu's Black Flag forces continued to harass and fight the French in Tonkin after the end of the Sino-French War.[4]

With support from China, Vietnamese and Chinese freebooters fought against the French in Lạng Sơn in the 1890s.[5] They were labelled "pirates" by the French. The Black Flags and Liu Yongfu in China received requests for assistance from Vietnamese anti-French forces.[6][7][8][9][10] Pirate Vietnamese and Chinese were supported by China against the French in Tonkin.[11] Women from Tonkin were sold by pirates.[12] Dealers of opium and pirates of Vietnamese and Chinese origin in Tonkin fought against the French Foreign Legion.[13]

The bandits and pirates included Nung among their ranks. By adopting their clothing and hairstyle, it was possible to change identity to Nung for pirate and exile Chinese men.[14] Pirate Chinese and Nung fought against the Meo.[15] The flag pirates who fought the French were located among the Tay.[16]

In 1891 "Goldthwaite's Geographical Magazine, Volumes 1-2" said "FOUR months ago, a band of 500 pirates attacked the French residency at Chobo, in 'l‘onkin. They beheaded the French resident, ransacked and burned the town, and killed many of the people."[17] In 1906 the "Decennial Reports on the Trade, Navigation, Industries, Etc., of the Ports Open to Foreign Commerce in China and Corea, and on the Condition and Development of the Treaty Port Provinces ..., Volume 2" said "Piracy on the Tonkin border was very prevalent in the early years of the decade. Fortified frontier posts were established in 1893 by the Tonkin Customs at the most dangerous passes into China, for the purpose of repressing contraband, the importation of arms and ammunition, and specially the illicit traflic of women, children, and cattle, which the pirates raided in Tonkin and carried beyond the Chinese mountains with impunity. These posts were eventually handed over to the military authorities."[18] In 1894 "Around Tonkin and Siam" said "This, in my view, is too pessimist an estimate of the situation, a remark which also applies to the objection that these new roads facilitate the circulation of pirates. Defective as they may be, these roads must, it seems to me, be of service to cultivation and trade, and, therefore, in the long run to the pacification of the country."[19] In 1893 "The Medical World, Volume 11" said "Captain Hugot, of the Zouaves, was inclose pursuit of the fnmous Thuyet, one of the most redoubtable, ferocious, and cunning of the Black Flag (Annamite pirates) leaders, the man who prepared and executed the ambuscade at Hue. The captain was just about to seize the person of the young pretender Ham-Nghi, whom the Black Flags had recently proclaimed sovereign of Armani, when he was struck by reveral ar rows, discharged by the body-guard of HamNghi. The wounds were all light, scarcely more than scratches, and no evil effect was feared at the time. After a few days, however, in spite of every care, the captain grew weaker, and it became apparent that he was suffering from the effects of arrow poison. He was removed as quickly and as tenderly as possible to Tanh-Hoa, where he died in horrible agony a few days later, in spite of the most scientific treatment and the most assiduous attention."— National Druggist.[20] The 1892 "The Imperial and Asiatic Quarterly Review and Oriental and Colonial Record" said "The French port of Yen Long was surprised by Chinese and Annamite pirates and the troops driven out with loss."[21][22][23]

French and insurgent tactics

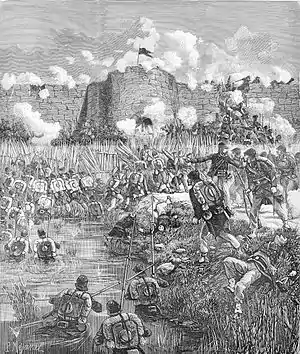

The terrain of Tonkin was ideal for the hit-and-run tactics used by the insurgents. In the flat and fertile Delta, the insurgents were able to move much more quickly than the French from village to village along the dykes that separated the flooded rice paddies. Most Tonkinese villages were encircled with earth walls, ponds and thick bamboo hedges, and were consequently difficult to attack. If a band of insurgents was detected by the French, it could choose either to disperse or to strengthen a village's fortifications and wear the French down by fighting a regular defensive battle. In the mountainous regions of Upper Tonkin, the insurgents could exploit the scarcity of paths and the difficulties the French faced in supplying their columns to build strong lairs in nearly inaccessible spots. From these hideouts they would fan out into the surrounding regions, laying ambushes for French detachments. As the French troops they met were often sick and exhausted, these ambushes were sometimes successful.[24]

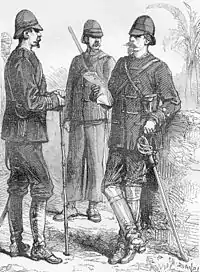

To counter these tactics, the French used 'shandy columns' (colonnes panachées), so-called because they normally contained a mix of white and native troops. Typically, a column would contain legionnaires and marine infantry, supported by companies of Tonkinese riflemen. To find the bandits, the French had to march into forests on the basis of imprecise and often misleading intelligence. When they discovered their position, they attacked, but in most cases it had already been abandoned for another. It was a tiring and frustrating struggle, which was not even interrupted during the stormy heats and the rains of summer. The soldiers of the Foreign Legion soon learned that it was more merciful to shoot wounded comrades who could not keep up with the marching columns than to leave them to be captured and tortured to death by the bandits.

For several years the French had frustratingly little to show for the enormous military efforts they were making to crush the insurgency. This was above all due to the duality of the command. The regional commanders only had military powers, and in all their operations had to obtain the agreement of the native authorities and the residents of the administrative provinces corresponding to their region. The residents themselves were assisted by merchants who improvised a transport business on which the supply of food and ammunition to the posts depended, and there was no recourse against these entrepreneurs if they failed to fulfil their engagements. Military action under such conditions could be neither swift nor sure. The insurgency resumed as soon as the columns had left, and the installation of posts in some important points did not, as had been hoped, win the French control of the country. Nevertheless, the French did win some successes, and by the end of 1890 the Delta was almost pacified and the insurgent bands had been pushed back into Upper Tonkin.[25]

Progress of the pacification

Beyond the Delta, however, the French had much less to show for their efforts. Their first major victory against the insurgents, at Ba Dinh in January 1887, owed more to the folly of the Vietnamese commander Dinh Cong Trang, who deliberately challenged the French to a set-piece battle near the Annam-Tonkin border, than to the skill of the French high command. The Vietnamese defeat at Ba Dinh was a disaster for the Cần Vương movement in Annam, and cost the lives of many Vietnamese insurgents, but it did little to lessen the problems that the French faced in Tonkin.[26]

The collapse of the Cần Vương insurgency in Annam at the end of 1888 also did little to alter the state of affairs in Tonkin. Only two months after the capture of the young Vietnamese emperor Hàm Nghi in October 1888 a French column of 800 men under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Borgnis-Desbordes incurred heavy casualties (95 men killed and wounded) driving a strong force of insurgents from the villages of Cho Moi and Cho Chu on the Song Cau River.

Nevertheless, though resistance continued behind their lines, the French were able to widen their zone of occupation slowly but surely. In western Tonkin, a column under the command of chef de bataillon Bergougnioux advanced up the Clear River and occupied Bac Muc and Vinh Thuy in May 1886.[27] On 1 September 1887 the French occupied Hà Giang. A column under Colonel Brissaud penetrated almost as far as the border with Siam and dislodged a Siamese force that had taken advantage of the chaos in Tonkin to cross the frontier and occupy the small town of Dien Bien Phu.

In northern Tonkin Commandant Servière traversed the region between Lạng Sơn and Zhennan Pass at Cua Ai, and protected the operations of the Border Delimitation Commission set up under the Treaty of Tientsin to demarcate the frontier between Vietnam and China. He dispersed several insurgent bands that had been operating around Lạng Sơn, and established a post at Chi Ma, on the Tonkin-Guangxi border.[28] In November 1886 a large expedition under the command of General Mensier drove the insurgents from other localities near the Tonkin-Guangxi border and occupied the important frontier town of Cao Bằng.[29]

Considerable progress was also made in eastern Tonkin, a region that had seen little fighting during the Sino-French War and was still almost unexplored by the French. Between 1886 and 1888 capitaine de vaisseau de Beaumont's naval division hunted down the pirates who still infested Along Bay and most of the Delta coasts and completed the work that Admiral Amédée Courbet had begun in 1884. The wild country between Lạng Sơn and the Guangdong border that the French had been unable to subdue during the war with China was now tamed by the French occupation of Tien Yen, Ha Coi and Mong Cai. A vital preliminary to these operations was the completion of the naval survey of the coast of Tonkin by the naval hydrographer La Porte, who took over the work begun in 1883 by Renaud and Rollet de l'Isle. La Porte's moment of glory came when, as a result of this survey, he personally guided the French gunboats up the narrow river channels to Mong Cai, enabling the French to confront the town's defences with overwhelming strength. Mong Cai was occupied by the French in December 1886. La Porte crowned his career by making a general triangulation of Tonkin, from Haiphong to Hưng Hóa and to Phu Lang Thuong, drawing on a series of topographical maps produced since 1883 by military engineering officers. Finally, a column of 600 soldiers and 400 coolies under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Alphonse Dugenne, the hero of the Bắc Lệ ambush in June 1884, marched along the coastal plain of eastern Tonkin as far as the Chinese border and explored the sparsely-populated and mountainous hinterland running back to Lạng Sơn.[30] The French completed their penetration of eastern Tonkin in January 1887 by driving insurgent bands from the Pak Lung peninsula, a border region disputed between Vietnam and China. In July 1887 the peninsula was awarded to China by the Border Delimitation Commission.[31]

A joint political and military solution

The tide finally turned in France's favour in Tonkin with the appointment of Jean-Marie de Lanessan as governor-general of Indochina in 1891. De Lanessan, an able, intelligent and energetic administrator, quickly put in place the administrative structures that would enable the military commanders first to contain and ultimately to master the insurrection. He reversed the policy of his predecessors, recalling the unwieldy militia units to the Delta and returning control of the mountain region of Tonkin to the military. He divided Upper Tonkin into four territories, centred respectively on Sept Pagodes, Lạng Sơn, Sơn Tây and Sơn La, and placed each territory under the orders of a military commander who was also entrusted (subject to his own oversight) with the civil powers of a résident supérieur. This concentration of military and civil power in the hands of a small number of officers was potentially dangerous, but de Lanessan got on well with General Duchemin, the army commander in Tonkin, and was able to ensure that the commands went to the best officers available. These men included Lieutenant-Colonel Théophile Pennequin, who developed the famous 'oilstain' (tache d'huile) tactics that were eventually to prove so effective in stamping out the insurgency, Colonels Joseph Gallieni and Servière, and chef de bataillon Hubert Lyautey. De Lanessan was lucky. Duchemin and his immediate subordinates were among the finest soldiers then serving in France's colonial empire. Two of them, Joseph Gallieni and Hubert Lyautey, would distinguish themselves in the First World War and end their lives as Marshals of France.[32]

This galaxy of talented administrators and soldiers pursued French aims in Tonkin with a judicious mixture of political and military action. Political action came first. De Lanessan and Gallieni agreed that the most important task for the French was to win over the population to their side. If the ordinary Tonkinese farmers could be persuaded that French rule was preferable to anarchy, they would cooperate with the colonial power. The insurgents would eventually be isolated, and military victory would then follow as a matter of course. Accordingly, the French set out to demonstrate the benefits of their rule. Roads and paths were built to link up the French posts, enabling small French columns to move quickly from place to place. As it became easier for the French to protect law-abiding villagers from the depredations of the bandits, confidence gradually returned. Markets and schools were built in the villages, and the conditions were established in which agriculture, industry and commerce could once more flourish.[33]

Seeing that the French were there to stay, and that they were increasingly capable of imposing law and order, the Tonkinese gradually turned against the insurgents. The French began to receive valuable intelligence on the whereabouts of guerrilla bands. Eventually, they felt secure enough to form local militia units to protect the villages, at last certain that their rifles would be turned against the bandits rather than against themselves. At this point the scales tipped decisively against the insurgents. Once they had lost the sympathy of the local population, they could not hope to win.[33]

With the ground thus prepared politically, the French were able to implement Pennequin's 'oilstain' method with considerable success. This method involved building a strong barrier of solid posts, judiciously placed, to push back the insurgents little by little, to occupy effectively the conquered terrain, and to establish new posts further forward. The French did not enter a new troubled region until they had finished with the previous one. The dispatch of attack columns became the exception, and was used only to achieve a clear objective that could not be achieved by political means.[32]

Gradual collapse of the insurgency

In this way, the French were able between 1891 and 1896 to reduce the final centres of resistance in Tonkin. In November 1891 they finally secured control of the Dong Trieu massif, a thorn in their side since 1884, and dispersed the Chinese guerrillas who had operated there for so long. Trouble in the region subsided immediately on the death of the insurgent leader Luu Ky a few months later. In March 1892 the French destroyed the last bandit concentrations in the Yen The region. This remote, wooded, mountain fastness between Tuyên Quang and Thái Nguyên had been colonised by guerrilla bands during the war with China and held against the French ever since by the bandit chiefs Ba Phuc, De Nam and De Tham. Although French troops continued to skirmish with bandits in the Yen The until De Tham's death in 1913, they were no longer a serious threat to law and order. With the removal of these two running sores, the French were able to scale down their military operations in Tonkin between 1892 and 1896 to a very low level. The insurgents, once so formidable, were now reduced to kidnapping isolated French and Vietnamese officials and demanding ransoms for their safe return. They had become a nuisance rather than a threat. Routine sweeps and patrols by single companies now sufficed to police both the Delta and the mountain regions, and in 1896 it became possible for French politicians to speak of the 'pacification' of Tonkin with genuine conviction.[34]

Frontier security

As internal order was restored, the security of the border with China loomed larger. The border had long been porous, and Chinese bands took advantage of the weakness of the French frontier garrisons to cross over into Tonkin, plunder as many villages as they could, then retreat back into China before the French could catch up with them. In 1887 China and France had agreed on the delimitation of the frontier, but this agreement proved to be almost worthless in practice, because the Chinese authorities in the frontier districts actively connived at the activities of the raiders. Indeed, the raiding bands often consisted of parties of regular soldiers of the Guangxi and Yunnan armies. Some French commanders, notably Gallieni, raided villages on the Chinese side of the border in retaliation, or conducted 'hot pursuit' operations across the border into China to track down bands of raiders. Formally, France and China now enjoyed the best of relations, and both the French and Chinese governments turned a blind eye to such incursions. Frontier security for Tonkin was finally achieved in the closing years of the nineteenth century, after the French lined the border with China with blockhouses and stationed enough soldiers there to deter incursions.

Notes

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 166

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 275–7, Histoire militaire, 125

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 284–5

- ↑ Micheline Lessard (24 April 2015). Human Trafficking in Colonial Vietnam. Routledge. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-1-317-53622-2.

- ↑ Douglas Porch (11 July 2013). Counterinsurgency: Exposing the Myths of the New Way of War. Cambridge University Press. pp. 52–. ISBN 978-1-107-02738-1.

- ↑ David G. Marr (1971). Vietnamese Anticolonialism, 1885-1925. University of California Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-520-04277-3.

- ↑ Paul Rabinow (1 December 1995). French Modern: Norms and Forms of the Social Environment. University of Chicago Press. pp. 146–. ISBN 978-0-226-70174-5.

- ↑ Le Tonkin: ou la France dans l'Extrême-Orient. Hinrichsen. 1884. pp. 64–.

- ↑ Henri Frey (1892). Pirates et rebelles au Tonkin: nos soldats au Yen-Thé. Hachette.

- ↑ "1898 ATM7 Indochine Tonkin de Tham Pirates Yen the Annamites NHA Gue | eBay". Archived from the original on 2016-08-22. Retrieved 2016-06-03.

- ↑ Benerson Little (2010). Pirate Hunting: The Fight Against Pirates, Privateers, and Sea Raiders from Antiquity to the Present. Potomac Books, Inc. pp. 205–. ISBN 978-1-59797-588-9.

- ↑ Micheline Lessard (24 April 2015). Human Trafficking in Colonial Vietnam. Routledge. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-1-317-53622-2.

- ↑ Jean-Denis G.G. Lepage (11 December 2007). The French Foreign Legion: An Illustrated History. McFarland. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-7864-3239-4.

- ↑ Jean-Pascal Bassino; Jean-Dominique Giacometti; Kōnosuke Odaka; Suzanne Ruth Clark (2000). Quantitative economic history of Vietnam, 1900-1990: an international workshop. Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University. p. 375.

- ↑ John Colvin (1996). Volcano Under Snow: Vo Nguyen Giap. Quartet Books. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-7043-7100-2.

- ↑ Jean Michaud (19 April 2006). Historical Dictionary of the Peoples of the Southeast Asian Massif. Scarecrow Press. pp. 232–. ISBN 978-0-8108-6503-7.

- ↑ Goldthwaite's Geographical Magazine. Wm. M. & J.C. Goldthwaite. 1891. pp. 362–.

- ↑ China. Hai guan zong shui wu si shu (1906). Decennial Reports on the Trade, Navigation, Industries, Etc., of the Ports Open to Foreign Commerce in China and Corea, and on the Condition and Development of the Treaty Port Provinces ... Statistical Department of the Inspectorate General of Customs. pp. 464–.

- ↑ Around Tonkin and Siam. Chapman & Hall. 1894. pp. 73–.

tonkin pirates.

- ↑ The Medical World. Roy Jackson. 1893. pp. 283–.

- ↑ Asian Review. East & West. 1892. pp. 234–.

- ↑ The Imperial and Asiatic Quarterly Review and Oriental and Colonial Record. Oriental Institute. 1892. pp. 1–.

annamite pirates.

- ↑ LA REVUE SOCIALISTE. 1892. pp. 209–.

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 285

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 285–6

- ↑ Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 139–40

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 283; Histoire militaire, 130

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 283

- ↑ Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 137

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 283–4

- ↑ Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 133–4

- 1 2 Thomazi, Conquête, 286

- 1 2 Thomazi, Conquête, 287

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 286–7

References

- Fourniau, C., Annam–Tonkin 1885–1896: Lettrés et paysans vietnamiens face à la conquête coloniale (Paris, 1989)

- Fourniau, C., Vietnam: domination coloniale et résistance nationale (Paris, 2002)

- Porch, D., The French Foreign Legion (New York, 1991)

- Sarrat, L., Journal d'un marsouin au Tonkin, 1883–1886 (Paris, 1887)

- Thomazi, A., Histoire militaire de l'Indochine française (Hanoi, 1931)

- Thomazi, A., La conquête de l'Indochine (Paris, 1934)