The Packers sweep, also known as the Lombardi sweep, is an American football play popularized by Green Bay Packers coach Vince Lombardi. The Packers sweep is based on the sweep, a football play that involves a back taking a handoff and running parallel to the line of scrimmage before turning upfield behind lead blockers. The play became noteworthy due to its extensive use by the Packers in the 1960s, when the team won five National Football League (NFL) Championships, as well as the first two Super Bowls. Lombardi used the play as the foundation on which the rest of the team's offensive game plan was built. The dominance of the play, as well as the sustained success of Lombardi's teams in the 1960s, solidified the Packers sweep's reputation as one of the most famous football plays in history.

The sweep

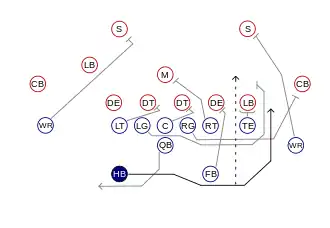

The Packers sweep is a variation on the sweep, which is a basic running play in American football. A sweep play involves a back, typically the halfback or running back, taking a pitch or handoff from the quarterback and running parallel to the line of scrimmage. This allows the offensive linemen (usually the guards) and the fullback to block defenders before the runner turns upfield.[1] The sweep can be run out of multiple formations and go either left or right of the center. It is characterized as power football[2] and usually gives the runner the choice to follow the lead blockers inside or outside, depending on how the defense reacts.[3] Various options and changes to the sweep have been implemented to create further deception. These include running option pass plays out of the same formation,[4] changing which blockers pull from the line of scrimmage, and running the play towards different areas of the field.[1]

Early development

The development of what became known as the Packers sweep began with Vince Lombardi.[1][3] He played football at Fordham University on a football scholarship,[5] and was part of the "Seven Blocks of Granite", a nickname for the team's offensive line.[6] This was the first time Lombardi witnessed the success of the sweep. Jock Sutherland's University of Pittsburgh teams used the sweep extensively against Lombardi's team in an era when the single-wing formation was used almost universally.[5] In 1939, after graduation, Lombardi began his coaching career as an assistant at St. Cecilia High School in Englewood, New Jersey. He was promoted to head coach and over eight seasons led St. Cecilia's to multiple championships. With a 32-game unbeaten streak, the school had one of the top high school football programs in the nation.[7] Lombardi attended coaching clinics during this time, where he continued to develop a better understanding of the sweep, especially the techniques of pulling offensive linemen and having the ball carriers cut back towards openings in the line.[8] He moved on from high school to college football as an assistant under Earl "Red" Blaik at West Point in 1948.[6] For five seasons Lombardi served as an assistant coach and further developed his coaching abilities. Blaik's emphasis on players executing their job and the military discipline of West Point greatly influenced Lombardi's future coaching style.[8]

Lombardi's first NFL coaching job came in 1954, when he accepted an assistant coaching job (now known as an offensive coordinator) for the New York Giants.[6][8] It was with the Giants that Lombardi first implemented the principles that became the Packers sweep. He started to run the sweep using the T formation and positioned his linemen with greater space between each other.[9] He also had offensive tackles pull from the line and implemented an early variant of zone blocking (blockers are expected to block a "zone" instead of an individual defender); this required the ball carrier to run the football wherever there was space.[8] The phrase "running to daylight" was later coined to describe the freedom the ball carrier had to choose where to run the play.[10] Under his offensive leadership and assisted by his defensive counterpart Tom Landry, Lombardi helped guide the Giants to an NFL Championship in 1956.[11] They appeared again in the 1958 Championship Game, this time losing in overtime to the Baltimore Colts.[8][12] In 1959, Lombardi accepted a head coaching and general manager position with the struggling Green Bay Packers.[6] The Packers had just completed their worst season in team history with a record of 1–10–1.[13] Even though the Packers had not been successful for a number of years, Lombardi inherited a team in which five players would go on to be Pro Football Hall of Famers.[14][15] He immediately instituted a rigorous training routine, implemented a strict code of conduct, and demanded the team continually strive for perfection in everything they did.[8]

Implementation

The first play Lombardi taught his team after he arrived in Green Bay was the sweep.[8] He moved Paul Hornung to the halfback position permanently (in the past he had been poorly utilized in different back positions) and made him the primary ball-carrier for the sweep.[16] The Packers sweep, as it became known, was the team's lead play and the foundation on which the rest of the offensive plan was built.[9][17] For the team to succeed, Lombardi drilled them constantly on the play, expecting it to be executed perfectly every time (it was common for the team to run the play at the beginning and end of every practice). [18][19] The play became the epitome of Lombardi's philosophy: a simple, fundamentally sound play that was reliant on the entire team working together to move the ball.[8][10]

Even though each player had a role to perform, the execution of the center, the pulling guards, and the halfback were essential to the play's success.[17] The center had to cut off the defensive tackle or middle linebacker to prevent the defender from breaking up the play behind the line of scrimmage.[20] This was due to the right guard (when the play was run to the right side of the field), who would vacate this space while pulling to lead the ball carrier. The most difficult block fell on the left guard, who had to pull the whole way across the field to be the lead blocker.[5] The left guard also had to decide, based on how the defense reacted, whether to push the play to the inside or outside of the tight end.[20] The ball carrier, usually the halfback, then decided whether to go inside or outside as well.[1][14] The fullback, tight end, and left tackle also had essential blocks that dictated the success of the play.[17][21]

There's nothing spectacular about it. It's just a yard-gainer. But on the sideline, when the sweep starts to develop, you can hear those linebackers and defensive backs yelling, 'Sweep!' 'Sweep!' and almost see their eyes pop as those guards turn upfield after them. It's my No. 1 play because it requires all 11 men to play as one to make it succeed, and that's what team means.

For nine seasons Lombardi ran the Packers sweep with great success,[23] with one estimate claiming the play gained an average of 8.3 yards each time it was run in the first three seasons under Lombardi.[14] Overall though, the play was known as gaining "four-yards-and-a-cloud-of-dust" that would allow the Packers to control the game clock, slowly moving the ball down the field and exhausting the defense.[1]

Even when defenses shifted to try to stop it, Lombardi would either attack other weaknesses or would run variations of the sweep.[24] One variation, although rare, was running the sweep towards the weak side, typically to the left of the runner.[25] Tom Landry, as head coach of the Dallas Cowboys, had his defense linemen "flex" (line up in an offset position) to prevent the runner from finding the cutback lanes that were essential to the success of the sweep. In response to Landry's flex defense, Lombardi would run other types of running plays attacking the new positions of the defensive linemen.[8] Lombardi would also counter other defensive adjustments by running the sweep to the left side, having various blockers not pull, switching the ball carrier, or running option pass plays—each of which could be run out the sweep formation.[10][26]

Other coaches in the league had great respect for the Packers sweep, although most acknowledged the success of the play was based on two criteria: great players and perfect execution. [5][27] During his tenure, Lombardi had three offensive linemen (Jim Ringo, Forrest Gregg, and Jerry Kramer), two backs (Hornung and Jim Taylor), and one quarterback (Bart Starr) who were later elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.[28] Each of those offensive players was instrumental to the success of the Packers sweep and thus the offense. Ringo, Gregg, Kramer, and Taylor each provided key blocks for Hornung to run the sweep. Starr (who as the quarterback orchestrated the play) and Taylor were essential to variations of the sweep that called for different runners or option pass plays.[10] In addition to the Hall of Famers, Lombardi's teams included other highly decorated players, such as first-team All-Pro Fuzzy Thurston,[29] the left guard who had the most challenging blocking assignment in the sweep.[5][23] Many of these players identified Lombardi's coaching and drive for perfection as important factors behind their accomplishments and the team's success.[5][6][16]

Legacy

At its core, the Packers sweep was a simple play that relied on all members of the team precisely executing their responsibilities.[3][9][17] This level of teamwork, coordination, and execution epitomized the Packers of the 1960s under Lombardi.[19] In nine seasons at the helm, Lombardi and his sweep led the Packers to five NFL championships, as well as victories in Super Bowl I and II.[23] The team won three straight championships in 1965, 1966, and 1967—only the second team to accomplish this feat (the other being the 1929, 1930, and 1931 Packers).[30]

Six offensive players who played under Lombardi in the 1960s were later elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame; Lombardi was elected shortly after his death in 1970.[28] Three of these Packers (Hornung, Starr, and Taylor) won NFL MVP awards in the 1960s.[31][32][33] Much of the Packers' offensive success was based on the threat of running the sweep. Lombardi exploited the dominance of the play to take advantage of defenses and run the offense to his team's strengths.[3] This sustained success established the Packers sweep as one of the most famous football plays in history.[17][19]

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gruver 1997, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 Gulbrandsen 2011, p. 80.

- ↑ Bell, Jarrett (September 24, 2008). "Odd formations could become latest fad across NFL". Gannett Company. Archived from the original on January 6, 2012. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gruver 1997, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Greatest Coaches in NFL History – 1. Vince Lombardi: Simply the best". ESPN Internet Ventures. June 11, 2013. Archived from the original on July 7, 2018. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- ↑ O'Connor, Ian (January 23, 2014). "Gospel of St. Vince". ESPN Internet Ventures. Archived from the original on July 7, 2018. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Gruver 1997, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Maraniss 1999, p. 222.

- ↑ Sell, Jack (December 31, 1956). "Giants crush Bears in title game, 47–7". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 12. Archived from the original on May 27, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2018 – via Google News Archive.

- ↑ Sandomir, Richard (December 4, 2008). "The 'Greatest Game' in Collective Memory". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 7, 2018. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- ↑ Johnson, Chuck (January 29, 1959). "Packers name Vince Lombardi head coach, general manager". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. p. 11, part 2. Archived from the original on May 19, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2018 – via Google News Archive.

- 1 2 3 Fox, Bob (July 25, 2014). "Green Bay Packers: Jerry Kramer Talks About the Power Sweep". Turner Broadcasting System. Archived from the original on July 7, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ↑ "For Hall of Famer Jerry Kramer, Packers' honor was 'kick in the stomach'". Green Bay Press-Gazette. September 16, 2018. Archived from the original on March 20, 2023. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- 1 2 Hendricks, Martin (January 21, 2009). "Hornung set the solid-gold standard". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Archived from the original on July 7, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Christl, Cliff (February 1, 2018). "Jerry Kramer was lineman at forefront of Lombardi's power sweep". Packers.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ↑ Maraniss 1999, p. 225.

- 1 2 3 Gruver 1997, p. 4.

- 1 2 Maraniss 1999, p. 223.

- ↑ Maraniss 1999, p. 224.

- ↑ Reischel 2013, p. 124.

- 1 2 3 Weber, Bruce (December 15, 2014). "Fuzzy Thurston, Big Broom in the Packers' Great Sweep Play, Dies at 80". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 7, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ↑ Lombardi & Heinz 1963, p. 85.

- ↑ Christl, Cliff (February 13, 2020). "Teaching Lombardi's power sweep not that complicated". Packers.com. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ↑ Lombardi & Heinz 1963, p. 131.

- ↑ Lombardi & Heinz 1963, p. 14.

- 1 2 "Pro Football Hall of Famers by Franchise". Pro Football Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on October 15, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ↑ Christl, Cliff (July 4, 2019). "Fuzzy Thurston a 'guardian angel' on famous power sweep". Packers.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ↑ "NFL Champions 1920–2015". Pro Football Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ↑ "Hornung Is 'Most Valuable'". Star Tribune (clipping). Associated Press. December 21, 1961. p. 21. Archived from the original on July 8, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Hand, Jack (December 15, 1966). "Bart Starr Most Valuable Player". The Morning Record (clipping). Associated Press. p. 9. Archived from the original on October 1, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Jim Taylor Player of Year and Allie Sherman Coach of Year in NFL Voting". The Evening Times (clipping). Associated Press. December 13, 1962. p. 14. Archived from the original on July 8, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

Bibliography

- Dunnavant, Keith (2012). Bart Starr: America's Quarterback and the Rise of the National Football League. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-36349-9.

- Gruver, Ed (1997). "The Lombardi Sweep" (PDF). The Coffin Corner. 19 (5). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 7, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018 – via Professional Football Researchers Association.

- Gulbrandsen, Don (2011). Green Bay Packers: The Complete Illustrated History – Third Edition. MVP Books. ISBN 978-0760342220. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2018 – via Google Books.

- Lombardi, Vince; Heinz, W. C. (1963). Run to Daylight!. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4767-6717-8.

- Maraniss, David (1999). When Pride Still Mattered: A Life of Vince Lombardi. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-618-90499-0.

- Reischel, Rob (2013). 100 Things Packers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die. Chicago, IL: Triumph Books. ISBN 978-1600788703.

.jpg.webp)