Paeanius (Greek: Παιάνιος Paianios, c. 327 – c. 379),[lower-roman 1] was a late Roman lawyer and translator who lived in the Eastern provinces. He was author of a translation into Greek language of the Latin historical work of Eutropius, the Breviarium ab urbe condita (or Breviarium historiae Romanae). His translation, which has survived in a handful of manuscripts, is a rare example of a near-contemporary translation from Latin to Greek, as Eutropius’s Breviarium was written in 369 and translated by Paeanius around 379.

Biography

Paeanius’s life can be reconstructed from various sources. His name is attested in the subscription to his translation. In the letters of Libanius, a prominent orator and teacher of rhetorics in the 4th century, Paeanius is mentioned several times (in the Attic form Paionios, Greek: Παιώνιος).

Paeanius was born around 337 into a wealthy family of Antioch.[2][3] His father Calliopius had studied rhetorics with Zenobius and later served in the imperial administration.[4] In a letter from 363, Libanius names Paeanius as a student of his as well as of his colleague/rival Acacius of Caesarea when both taught rhetorics in Antioch (354–361). During that time, both rhetors took great care towards Paeanius.[3][5] Other letters reveal that in 364 Paeanius was on a journey to Macedonia and Constantinople, the Eastern capital.[3][6] Later that year Paeanius returned to Antioch and Libanius informs of his plans to study law in the famous Roman Law school in Berytus.[7] While still in Antioch, Paeanius made advances to marry the daughter of a wealthy Antioch citizen, Pompeianus, and by 365 had succeeded.[8][3]

Since Libanius also mentions a historian named Eutropius in a 362 letter, scholars assume that he referred to Eutropius the author of the Breviarium.[9][10] The historian had accompanied emperor Julian on his Persian campaign in 363 and thus had resided in the East around that time. Based on the assumption that Eutropius and Paeanius had both studied with Libanius and Acacius, they may well have been acquaintances. Otto Seeck, a historian specialising in late antiquity and an expert on Libanius’s letters, has suggested that Eutropius may himself have asked Paeanius to translate the Breviarium into Greek.[11] Additionally, the historian Joseph Geiger has linked both Eutropius and Paeanius with the Greco-Latin community of Caesarea Maritima and suggested a common origin for both.[12]

Of Paeanius’s work as an advocate we have no further notice. The last piece of information is the year when he wrote his translation of Eutropius’s Breviarium, which can be inferred from the work itself: In book 9, chapter 24, where Eutropius mentions the Persian king Narseh, Paeanius adds an explanatory note:

πάππος δὲ ἦν οὗτος Σάπωρί τε καὶ Ὁρμίσδῃ τοῖς εἰς τὴν ἡμετέραν ἡλικίαν ἀφικομένοις.

He was the grandfather of Shapur and Hormizd, who have lived into our own age.— Paeanius, Metaphrasis book 9, chapter 24

Paeanius’s use of the aorist participle has since his first editor Sylburg been taken as a sign that the Metaphrasis was composed around the year 379 when Shapur II died, as Paeanius assumed his audience to be familiar with the name from their own lifetime.[13][2][14]

Given his association with Libanius and Eutropius as well as the total absence of Christian themes in his translation, Paeanius is generally assumned to have been a pagan Hellene. This has not deterred Christian authors such as Socrates of Constantinople or Nicephorus Gregoras from making extended use of his translation.

Paeanius’s Metaphrasis (Translation)

Paeanius wrote a translation of Eutropius’s short Roman history, which had originally been published around 369 at the request of the emperor Valens. In his dedication letter to the emperor, Eutropius gave a short description of the aims of his work while simultaneously paying homage to the emperor. Paeanius in his translation left out this dedication letter and instead jumped straight into the matter. Keeping Eutropius’s partition of the work into ten small ″books″,[15] he translated the whole narrative from the foundation of the city to the death of emperor Jovian in 364. The first six books narrate events from the Roman republic, while the last four books cover the Principate and the Dominate periods.

As was customary in Ancient literature, Paeanius chose a liberal translation style where he applied both literal translations (even keeping to the order of the words) and paraphrase that captures the gist of his source. Paeanius produced a generally faithful translation, turning Eutropius’s succinct Roman prose into elegant, graceful Atticising style. However, he occasionally made mistakes due to misunderstanding the Latin, not being aware of the historical background or misreading number signs or proper names. In other cases, he intentionally left out or rearranged bits of information. He also famously added explanations for various Roman terms (such as senator, dictatura, legion, miliarium, imperator) or locations (the Alps, Aquileia) in order to make the work more accessible to a Greek-speaking audience.[16]

Reception and history of transmission

Reception during the 4th and 5th century

Paeanius’s translation was used by several Greek writers in the 5th century. It has been suggested that Philostorgius had used Eutropius, probably in Paeanius’s translation, for his Ecclesiastical history (written circa 425–433).[17] Shortly thereafter, Socrates of Constantinople in his Ecclesiastical history (written in the 440s) used Eutropius’s narrative both in Latin and in Paeanius’s Greek translation side-by-side.[18] Sozomen is his Ecclesiastical history (written around the same time and considered to be largely dependent on Socrates) in two places adds information originating from Eutropius whom he must have used in Paeanius’s translation.[19]

After this time nothing certain can be said about the reception of Paeanius’s translation because around 500 Capito of Lycia wrote another Greek translation, this one being (in part) closer to the original. Correlations between Eutropius and Greek historians from this age and later ages therefor are in a limbo where we cannot say with certainty which translation was used. While Paeanius’s translation has survived in at least one manuscript until the 12th century, the one of Capito is lost entirely. As the numerous Eutropian passages in John of Antioch’s Chronological history (written in the 6th or 7th century) bear no resemblance with Paeanius, they are generally assumed to stem from Capito.

Manuscript transmission and revival of interest during the Palaeologan Renaissance

From the late 13th century, Paeanius was rediscovered during the Palaeologan Renaissance. Prominent scholars such as Maximus Planudes (ca. 1260–ca. 1305)[20] and Nicephorus Gregoras (ca. 1295–1360)[21] took care in creating full copies of his work as well as making excerpts from it and using it in their own works. Most notably Nicephorus quoted Eutropius (in Paeanius’s translation) as a pagan authority on the virtues of emperor Constantine and those of his father Constantius Chlorus when he wrote his Life of Constantine (BHG 369) between 1334/5 and 1341/2.[22]

During the Renaissance of the 15th century, when Western Europe rediscovered Greek learning, Paeanius’s translation was brought to Italy by two eminent scholars. Between 1464 and 1491, the manuscript created under Nicephorus Gregoras’ auspices was acquired for Lorenzo de' Medici's library in Florence. Also in the 1460s, probably before this purchase, cardinal Bessarion (1403–1472) issued another copy of the same manuscript which he bequested to the Library of Saint Mark in Venice after his death. Other copies went to Germany and France in the 16th century.

Printed editions and use as school text

The first printed edition was published in 1590 by Friedrich Sylburg in his collection of minor Greek writers of Roman history. Sylburg had acquired a copy of a copy (now lost) of the Laurentian manuscript. His edition has not only the merit of making Paeanius accessible for the public but also in his curation of the Greek text. Sylburg’s many suggestions for correcting (or keeping) the text remain invaluable for any editor or reader, even though his manuscript was flawed. After Sylburg, no efforts were made to substantially improve on his edition. While adding explanatory notes here and there, all later editors repeated Sylburg’s text almost without suggestions of their own.

While most of these editions featured Paeanius only as an addition to (the Latin text of) Eutropius, there were also editions of Paeanius on his own in 18th century Germany. This was due to (Eutropius and) Paeanius being used as introductory reading in high schools in Germany and the Netherlands during the 17th and 18th century. A notable example is Johann Friedrich Salomon Kaltwasser’s 1780 edition of Paeanius which features an elaborate introduction, explanatory notes and a copious index of Greek words and their Latin equivalents. Another example (from the Greek diaspora) is Neophytos Doukas’ 1807 edition which furbished Paeanius’s text with a translation into Modern Greek Katharevousa and presented both texts on facing pages. Doukas also filled in parts missing in the manuscript with translations of his own from Eutropius’s Latin version (book 6, chapters 9–11; book 7, chapter 4; book 10, chapters 12–18).

By the 19th century, however, Paeanius had fallen out of favor as a school author. He is only mentioned as a bad choice for older students by Friedrich Meinecke and as "having finally been done with" by Friedrich August Eckstein.

With the rise of classical scholarship in the early 19th century came an increasing demand for dependable critical editions. Even a non-canonical author such as Paeanius eventually profited from this in the wake of Theodor Mommsen’s work on Roman and Greek historians. In a groundbreaking 1870 essay, Ernst Schulze suggested identifying Paeanius with the individual known from Libanius's letters, characterised his translation and reported on two manuscripts that had a text superior to that of Sylburg.[13] This incited Mommsen to inquire about the manuscripts and direct his pupil Hans Droysen to publish Paeanius as part of his editio maior of Eutropius for the Monumenta Germaniae Historica which appeared in 1879. This edition, chiefly based on the Laurentian manuscript, offeres the best text since Sylburg and is still in use.

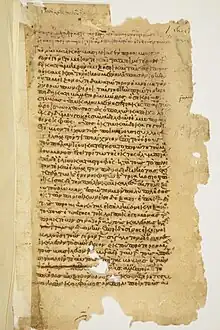

Unfortunately Mommsen and Droysen could not use the oldest and most complete of the manuscripts, the Codex Athous 4932 Iviron 812,[23] which was at the time only known from a handwritten 18th century catalogue. It was due to Spyridon Lambros' efforts from 1880 onward that the manuscripts of the Athos monasteries became known and accessible. Lambros himself rediscovered and first described the Iviron manuscript of Paeanius.[24] Lambros also published a full edition of Paeanius in his own one-man journal Neos Ellinomnimon in 1912. This edition has long been ignored, possibly due to its remote publication venue and its serious flaws (such as not taking note of important scholarship on the matter, misunderstand the mutual relationship of the manuscript witnesses and unreliably noting variants in the apparatus).[15] In the 1970s, Lambros' edition was reproduced as part of the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae and is available online to subscribed members.

Contents

| Book | Subject |

|---|---|

| 1 | The Roman Kingdom and early Roman Republic: From the foundation (753 BCE) to the Gallic sack of Rome (387 BCE) |

| 2 | Roman expansion in Italy: From the elections of military tribunes in 386 BCE to the end of the First Punic War (241 BCE) and establishment of Sicilia as first province |

| 3 | Establishment of Rome as the only power in the Western Mediterranean: From the end of the First Punic War to the end of the Second Punic War (212 BCE) |

| 4 | Rome conquers the Mediterranean: From the Second Macedonian War (200–197 BCE) to the Jugurthine War (112–106 BCE) |

| 5 | Rome averts several crises: From the Cimbrian War (113–101 BCE) to the Sulla's civil war (83–81 BCE) |

| 6 | more crises and end of the Roman Republic: From Lepidus' rebellion (78 BCE) and the Sertorian War to the First Triumvirate and the assassination of Julius Caesar (44 BCE) |

| 7 | establishment of the Roman empire (Principate): From the Liberators' civil war (43 BCE) and the Second Triumvirate to the death of emperor Domitian (96 CE) |

| 8 | Roman empire (Principate): From the reign of the emperors Nerva (96–98) and Trajan (98–117) to the assassination of emperor Severus Alexander (235) |

| 9 | Crisis of the Third Century: From the barracks emperors to the reformation of the empire under Diocletian (Tetrarchy) until his abdication (305) |

| 10 | later empire (Dominate): From the civil wars of the Tetrarchy to Julian's Persian expedition (363) and the death of his successor Jovian[lower-roman 2] |

Style and manner of the translation

In comparison to Eutropius’s Latin Breviarium, Paeanius’s translation has received mixed reviews by scholars, starting with his first editor Friedrich Sylburg, who chastised Paeanius’s ineptitude as a historian, his imperfect command of Latin or his liberal paraphrasing of his source.[25] Later editors followed suit, a good example being Hans Droysen’s judgement in the preface to his 1879 edition:

Paeanii versionis ab homine Graeco neque linguae Latinae admodum perito factae in usum Graecorum haec est indoles, ut Eutropii textum in universum non ad verbum vertat sed in brevius contrahat.

Paeanius’s translation (which was made for the use of a Greek audience by a Greek with questionable command of Latin and) is devised in such a way that he for the most part does not translate Eutropius’s text word-by-word but rather contracts it into a shorter version.[26]

A systematic analysis of Paeanius’s manner of translation was first attempted by Luigi Baffetti in 1922.

Further reading

- Groß, Jonathan (2020). "On the Transmission of Paeanius". Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies. 60 (3): 387–409. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3960022.

- Janiszewski, Pawel; Stebnicka, Krystyna; Szabat, Elzbieta (2015). Prosopography of Greek Rhetors and Sophists of the Roman Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 271 (no. 766). doi:10.1515/hzhz-2016-0029. ISBN 978-0-19871340-1.

- Malcovati, Enrica (1943–1944). "Le traduzioni greche di Eutropio". Rendiconti dell'Istituto Lombardo, Classe di Lettere e Scienze Morali (in Italian). 77: 273–304.

- Matino, Giuseppina (2017). "Peanio e il Latino". Κοινωνία (in Italian). 41: 43–59.

- Matino, Giuseppina (1993). "Due traduzioni greche di Eutropio". In Conca, Fabrizio; Gualandri, Isabella; Lozza, Giuseppe (eds.). Politica, cultura e religione nell'impero romano (secoli IV–VI) tra Oriente e Occidente. Atti del Secondo Convegno dell'Associazione di Studi Tardoantichi (in Italian). D'Auria. pp. 227–238. ISBN 978-8-87092092-5.

- Venini, Paola (1983). "Peanio traduttore di Eutropio". Memorie dell'Istituto Lombardo, Accademia di Scienze e Lettere, Classe di Lettere, Scienze Morali e Storiche (in Italian). 37 (7): 421–447.

External links

Notes

- ↑ Paeanius studied rhetorics with Libanius and Acacius sometime between 354–361. Assuming he was around 18–22 years old when he began his studies, his birth can be dated around 337.[1] His year of death is unknown, but it must have been after 379 when he published his translation of Eutropius.

- ↑ The manuscript transmission for Paeanius’s text breaks off in book 10, chapter 16 (characterisation of emperor Julian) but there is no reason to doubt that his work continued to the death of Jovian, as did Eutropius's Breviarium.

References

- ↑ Trivolis, Dionysios N. (1941). Eutropius Historicus καὶ οἱ Ἕλληνες μεταφράσται τοῦ Breviarium ab urbe condita. p. 129.

- 1 2 Trivolis, Dionysios N. (1941). Eutropius Historicus καὶ οἱ Ἕλληνες μεταφράσται τοῦ Breviarium ab urbe condita. p. 128.

- 1 2 3 4 Martindale, John R.; Jones, A. H. M.; Morris, John, eds. (1971). "Paeanius 1". The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire: Volume I, AD 260–395. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 657. ISBN 0-521-07233-6.

- ↑ Martindale, John R.; Jones, A. H. M.; Morris, John, eds. (1971). "Calliopius 1". The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire: Volume I, AD 260–395. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 174. ISBN 0-521-07233-6.

- ↑ Libanius, Epistula 1307,6 Foerster.

- ↑ Libanius, Epistulae 1225–1229 Foerster.

- ↑ Libanius, Epistula 1306 Foerster.

- ↑ Libanius, Epistulae 1324; 1488 Foerster.

- ↑ Libanius, Epistula 27 Fatouros/Krischer (see also pp. 321–322) = 754 Foerster.

- ↑ Pellizzari, Andrea (2013). "Tra Antiochia e Roma: il network comune di Libanio e Simmaco". Historikά. 3: 101–127, especially 115–116. doi:10.13135/2039-4985/762.

- ↑ Seeck, Otto (1906). Die Briefe des Libanius zeitlich geordnet. B. G. Teubner. p. 15.

- ↑ Geiger, Joseph (1996). "How Much Latin in Greek Palestine?". In Rosén, Hannah (ed.). Aspects of Latin. Papers from the Seventh International Colloquium on Latin Linguistics. Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck. pp. 39–58.

- 1 2 Schulze, Ernst (1870). "De Paeanio Eutropii interprete". Philologus. 29 (1–4): 285–299. doi:10.1524/phil.1869.29.14.285. S2CID 164421655.

- ↑ Fisher, Elizabeth (1982). "Greek Translations of Latin Literature in the Fourth Century". In Winkler, John J.; Williams, Gordon Willis (eds.). Later Greek Literature. Cambridge University Press. p. 189–193, especially 189. ISBN 978-0-51197292-8.

- 1 2 Groß, Jonathan (2020). "On the Transmission of Paeanius". Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies. 60 (3): 387–409. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3960022.

- ↑ The most comprehensive study of this topic is Baffetti, Luigi (1922). "Di Peanio traduttore di Eutropio". Byzantinisch-Neugriechische Jahrbücher. 3: 15–36.

- ↑ Van Nuffelen, Peter (2004). Un héritage de paix et de piété. Étude sur les histoires ecclésiastiques de Socrate et de Sozomène. Uitgeverij Peeters. p. 437.

- ↑ The most comprehensive study of this topic is Périchon, Paul (1968). "Eutrope ou Paeanius? L'historien Socrate se référait-il à une source latine ou grecque?". Revue des études grecques. 81 (386): 378–384. doi:10.3406/reg.1968.1056.

- ↑ Schoo, Georg (1911). Die Quellen des Kirchenhistorikers Sozomenos. Trowitzsch und Sohn. p. 86.

- ↑ Pérez Martín, Inmaculada (2015). "The role of Maximos Planudes and Nikephoros Gregoras in the transmission of Cassius Dio's Roman History and of John Xiphilinos' Epitome". Medioevo Greco. 15: 175–193.

- ↑ Clérigues, Jean-Baptiste (2007). "Nicéphore Grégoras, copiste et superviseur du Laurentianus 70,5". Revue d'Histoire des Textes. 2 N.S.: 21–47. doi:10.1484/J.RHT.5.101274.

- ↑ Leone, Pietro Luigi M. (1994). Nicephori Gregorae Vita Constantini. Cooperativa Universitaria Libraria Catanese. p. IX.

- ↑ "Diktyon no. 24407, ms. Iviron 812 (Lambros 4932)". Pinakes. Textes et manuscrits grecs (in French). Retrieved 2023-09-11.

- ↑ Lambros, Spyridon (1897). "Ein neuer Codex des Päanius". The Classical Review. 11 (8): 382–390. doi:10.1017/S0009840X00042013. S2CID 163259934.

- ↑ ″Optandum insuper et hoc fuisset, ut metaphrastes iste eadem ubique diligentia et fide metaphrasin pertexuisset. Sed ut is aliquammultis in locis addidit quae Eutropii verbis lucem ac splendorem afferunt, ita saepe inseruit quae plane sunt ἀνιστόρητα; nonnusquam etiam historiae partes plane pervertunt. Contra omittit nonnusquam propria nomina personarum, locorum, temporum; monetae item, et aliorum consimilium, quae ab accurato interprete praeteriri haudquaquam est consentaneum. Ad mutationem vero quod attinet, etsi ea non infeliciter interdum utitur, tamen saepenumero a mente auctoris ultra modum discedit. In quibus ut licentiam aliquam sibi usurpavit, ita in quibusdam se partim linguae, partim historiae minus peritum fuisse prodidit.″ (″One would have wished that this translator had composed his translation with equal diligence and close adherence to the original in all parts. Instead he not only frequently inserted certain phrases to bring more lucidity and splendour to Eutropius’s wording, he also added many things that are, frankly, ahistorical; in some instances, they truly pervert parts of the History. On the other hand, he sometimes omits proper names of persons, places, times; even currencies, and other things of the sort which a faithful translator should not be expected to cut. Like he took some liberty in these instances, he likewise reveals himself in others to be not very well acquainted with language and history.″) Friedrich Sylburg, Historiae Romanae scriptores Graecos, Frankfurt 1590, p. 62.

- ↑ Hans Droysen: Praefatio. In: Eutropii Breviarium ab urbe condita. Berlin 1879, p. XXII.