There were many different types of gladiators in ancient Rome. Some of the first gladiators had been prisoners-of-war, and so some of the earliest types of gladiators were experienced fighters; Gauls, Samnites, and Thraeces (Thracians) used their native weapons and armor. Different gladiator types specialized in specific weapons and fighting techniques. Combatants were usually pitted against opponents with different, but more or less equivalent equipment, for the sake of a fair and balanced contest. Most gladiators only fought others from within the same school or ludus, but sometimes specific gladiators could be requested to fight one from another ludus.

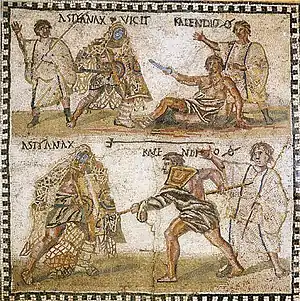

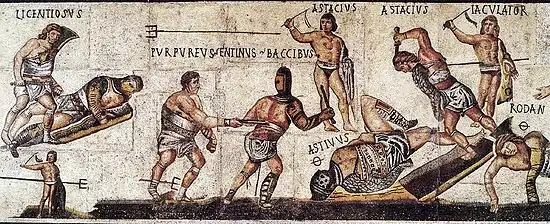

Elite gladiators wore high-quality decorative armour for the pre-game parade (Pompa). Julius Caesar's gladiators wore silver armour, Domitian's wore golden armour and Nero's wore armour decorated with carved amber. Peacock feathers were used for plumes while tunics and loincloths had patterns in gold thread. For the fighting, functional combat armour was used; this too could be elaborately decorated. Some artistic sources, such as reliefs and mosaics, show gladiators with a various number of tassels hanging from one arm or leg. It has been speculated that they were a form of "scorecard" to show the number of fights a gladiator had won.[1] Contests were managed by arena referees, and were fought under strict rules and etiquette.[2][3][4]

Combat was probably accompanied by music, whose tempo might have varied to match that of the combat. Typical instruments were a long straight trumpet (tuba), a large curved brass instrument (lituus), and a water organ (organum). During the Imperial period, the games might be preceded by a mimus, a form of comedy show. An image from Pompeii shows a "flute playing bear" (Ursus tibicen) and a "horn-blowing chicken" (Pullus cornicen), that may have been part of such a mimus.[5]

Gladiator types

The following list includes gladiators as typed by fighting style and equipment, general terms for gladiators, fighters associated with gladiatorial spectacles who were not strictly gladiators, and personnel associated with training or presentation.

Andabata

A "blindfolded gladiator", or a "gladiator who fought blind". Cicero jokingly refers to andabata in a letter to his friend Trebatius Testa, who was stationed in Gaul. The passage associates the andabata loosely with essedarii, chariot fighters.[6] The word is extremely rare in classical sources, and of doubtful etymology; Delamarre suggests it as a Latinised borrowing from Gaulish.[7]

Arbelas

The arbelas as gladiator type is mentioned only in the Oneirocritica of Artemidorus, which discusses dream-symbols and their significance in dream interpretation.[8] It may be related to the Greek word arbelos (ἄρβηλος), a cobbler's semicircular blade used to cut leather.[8][9][10]

Bestiarius

The bestiarius was a beast-fighter. See also Damnatio ad bestias.

Bustuarius

Bustuarius was a "tomb fighter," from bustum, "tomb", a generalised reference to the association of gladiatorial combat with funeral games (munera). Servius notes that it had once been "the custom to put captives to death at the graves of strong men, which later seemed a bit cruel, so it was decided to have gladiators fight at the tombs."[11] Even among gladiators, it was an unflattering term: Cicero used it to liken the morals of his enemy Clodius to those of the very lowest gladiator class.[12]

Cestus

The cestus was a fist-fighter or boxer who wore the cestus, a cross between a boxing glove and a heavy-duty type of knuckleduster, but otherwise had no armour.[13]

Crupellarius

The Roman historian Tacitus describes a Gaulish contingent of trainee, slave gladiators as crupellarii, equipped "after the national fashion" of Gallia Lugdunensis under Julius Sacrovir, during the Aeduian revolt of AD 21 against Rome. Tacitus has them "encased in the continuous shell of iron usual in the country", labouring under its weight, unable to fight effectively, rapidly tiring and soon dispatched by regular Roman troops. Tacitus' source could refer to a heavily armoured Roman "Gallus" type, which by Tacitus' own time had been developed and renamed as the murmillo.[14]

Dimachaerus

The dimachaerus (Greek διμάχαιρος, "bearing two knives") used a sword in each hand.[15]

Eques

Eques, plural equites, was a member of the middle-to-higher class of citizen-aristocracy, forbidden to take part in the games. Eques is also the regular Latin word for a horseman or cavalryman and a gladiator type. Early forms of the eques gladiator were lightly armed, with sword or spear. They had scale armour; a medium-sized round cavalry shield (parma equestris); and a brimmed helmet with two decorative feathers and no crest. Later forms also had greaves to protect their legs, a manica on their right arm and sleeveless, belted tunics. Generally, they fought only other equites.[16]

Essedarius

The essedarius (from the Latin word for a Celtic war-chariot, essedum) was likely first brought to Rome from Britain by Julius Caesar. Essedarii appear as arena-fighters in many inscriptions after the 1st century AD, apparently pitted against opponents of their own type. It is not known whether the essedarius entered the arena in his chariot, then dismounted and fought on foot, or fought while in the chariot. Some, or possibly all essedarii were driven by charioteers. No relevant pictorial evidence survives.[15]

Gallus

Literally a "Gaul"; either a prisoner of war, as in the earliest forms of munus, or else a gladiator equipped with Gaulish arms and armour, who fought in what Romans would have recognised as a "Gaulish style". Probably a heavyweight, and heavily armoured, the Gallus seems to have been replaced by, or perhaps transformed into, the murmillo, soon after Gaul's absorption as a Roman province.[17]

Gladiatrix

This refers to a female gladiator of any type. They were very rare, and their existence is poorly documented. They appear occasionally around the end of the Roman Republic and were banned by the emperor Septimius Severus by AD 200. The earliest known use of "gladiatrix" is post-Classical, in a 4th century gloss of Juvenal's comments on the beast-hunter Mevia.[18]

Hoplomachus

The hoplomachus (Romanised Greek for "armed fighter", Latin plural hoplomachii) wore quilted, trouser-like leg wrappings, loincloth, a belt, a pair of long shin-guards or greaves, an arm guard (manica) on the sword-arm, and a brimmed helmet that could be adorned with a plume of feathers on top and a single feather on each side. He was equipped with a gladius and a very small, round shield. He also carried a spear, which he would have to cast at his opponent before closing for hand-to-hand combat. The hoplomachi were paired against the myrmillones or Thraeces. They may have developed out of the earlier '"Samnite" type after it became impolitic to use the names of now-allied peoples.[19]

Laquearius

The laquearius may have been a kind of Paegniarius, or a type of retiarius who tried to catch his adversaries with a lasso (laqueus) instead of a net.[15]

Murmillo

The murmillo (plural murmillones) or myrmillo wore a helmet with a stylised fish on the crest (the mormylos or sea fish), as well as an arm guard (manica), a loincloth and belt, a gaiter on his right leg, thick wrappings covering the tops of his feet, and a very short greave with an indentation for the padding at the top of the feet. They are heavily armoured gladiators: the murmillo carried a gladius (64–81 cm long) and a tall, oblong shield in the legionary style. Murmillones typically fought a thraex, but occasionally the similar hoplomachus.[20]

Parmularius

A parmularius (pl parmularii) was any gladiator who carried a parmula (small shield), in contrast to a scutarius, who bore a larger shield (scutum). To compensate for this reduced protection, parmularii were usually equipped with two greaves, rather than the single greave of a scutarius. The thraex would have been named as parmularii.[21][22]

Provocator

In the late Republican and early Imperial era, the armament of a provocator ("challenger") mirrored legionary armature. In the later Imperial period, their armament ceased to reflect its military origins, and changes in armament followed changes in arena fashion only. Provocatores have been shown wearing a loincloth, a belt, a long greave on the left leg, a manica on the lower right arm, and a visored helmet without brim or crest, but with a feather on each side. They were the only gladiators protected by a breastplate (cardiophylax) which is usually rectangular, later often crescent-shaped. They usually fought with a tall, rectangular shield and the gladius, but the use of the spatha is also attested. They were paired only against other provocatores.[23]

Retiarius

The retiarius ("net fighter") developed in the early Augustan period. He carried a trident and a net, equipment styled on that of a fisherman. The retiarius wore a loincloth held in place by a wide belt and a larger arm guard (manica) extending to the shoulder and left side of the chest. He fought without the protection of a helmet. Occasionally a metal shoulder shield (galerus) was added to protect the neck and lower face. A tombstone found in Romania shows a retiarius holding a dagger with four spikes (each at the corner of a square guard) instead of the usual bladed dagger. A variation to the normal combat was a retiarius facing two secutores at the same time. The retiarus stood on a bridge or raised platform with stairs and had a pile of fist-sized stones to throw at his adversaries. While the retiarius tried to keep them at bay, the secutores tried to scale the structure to attack him. The platform, called a pons (bridge), may have been constructed over water.[24] Retiarii usually fought secutores but sometimes fought myrmillones.[25] There was an effeminate class of gladiator who fought as a retiarius tunicatus. They wore tunics to distinguish them from the usual retiarius, and were looked on as a social class even lower than infamia.[26][27]

Rudiarius

A gladiator who had earned his freedom received a wooden sword (a rudis) or perhaps a wooden rod (another meaning of the word rudis, which was a "slender stick" used as a practice staff/sword). A wooden sword is widely assumed, however, Cicero in a letter speaks of a gladiator being awarded a rod in a context that suggests the latter: Tam bonus gladiator, rudem tam cito accepisti? (Being so good a gladiator, have you so quickly accepted the rod?) If he chose to remain a gladiator, he was called a rudiarius. These were very popular with the public as they were experienced. Not all rudiarii continued to fight; there was a hierarchy of rudiarii that included trainers, helpers, referees, and fighters.[28][29]

Sagittarius

The sagittarius was an archer.

Samnite

The Samnite was an early type of heavily armed fighter that disappeared in the early imperial period. The Samnites were a powerful league of Italic tribes in Campania with whom the Romans fought three major wars between 326 and 291 BC. A "Samnite" gladiator was armed with a long rectangular shield (scutum), a plumed helmet, a short sword, and probably a greave on his left leg. It was frequently said that Samnites were the lucky ones since they got large shields and good swords. [30]

Scissor

The scissor (plural scissores) used a special short sword with two blades that looked like a pair of open scissors without a hinge. German historian and experimental archeologist Marcus Junkelmann has suggested that this type of gladiator fought using a weapon consisting of a hardened steel tube that encased the gladiator's entire forearm, with the hand end capped off and a semicircular blade attached to it.[31]

Scutarius

A scutarius was any gladiator who used a large shield (scutum), as opposed to any gladiator who used a small shield (parmularius). A murmillo or a secutor would be a scutarius; the additional protection or advantage afforded by the large shield was typically offset by the use of only one short greave, in contrast to the two greaves of a parmularius.

Secutor

The secutor ("pursuer") developed to fight the retiarius. As a variant of the murmillo, he wore the same armour and weapons, including the tall rectangular shield and the gladius. The helmet of the secutor, however, covered the entire face with the exception of two small eye-holes in order to protect his face from the thin prongs of the trident of his opponent. The helmet was also round and smooth so that the retiarius net could not get a grip on it.[32]

Thraex

The Thraex (plural Thraeces, "Thracians") wore the same protective armour as the hoplomachi with a broad rimmed helmet that enclosed the entire head, distinguished by a stylized griffin on the protome or front of the crest (the griffin was the companion of the avenging goddess Nemesis), a small round or square-shaped shield (parmula), and two thigh-length greaves. His weapon was the Thracian curved sword (sica or falx, c. 34 cm or 13 in long). They were introduced as replacements for the Gaulish gladiator type after Gaul made peace with Rome. They commonly fought myrmillones or hoplomachi.[33]

Veles

The veles (pl. velites, "skirmishers") is mentioned very rarely, and only in later sources. Velites are presumed to have fought on foot, armed with a spear, sword and small round shield (parma); this also assumes that the type was named for the early and lightly armed Republican army units of the same name. No depictions survive. [34][35][36]

Gladiator show fight in Trier in 2005.

Gladiator show fight in Trier in 2005. Nimes, 2005.

Nimes, 2005. Carnuntum, Austria, 2007.

Carnuntum, Austria, 2007.- Video of a show fight at the Roman Villa Borg, Germany, in 2011 (Retiarius vs. Secutor, Thraex vs. Murmillo).

Personnel associated with gladiators

Editor

The sponsor who financed gladiatorial spectacles was the editor, "producer."[37]

Lanista

The lanista was an owner-trainer of a troop of gladiators. He traded in slave gladiators, and rented those he owned out to a producer (editor) who was organizing games. The profession was often remunerative, but socially the lanista was on a par with a pimp (leno) as a "vendor of human flesh."[38]

Lorarius

The lorarius (from lorum, "leather thong, whip") was an attendant who whipped reluctant combatants or animals into fighting.[39]

Paegniarius

The paegniarius is known from literary sources as an entertainer who fought "burlesque duels" with blunted or mock weapons, especially during the midday break. A possible illustrative example from Pompei shows no helmet, shield or "weapons of attack", but what might be protective wrappings on the lower legs and head.[40] A paegniarius named Secundus enjoyed a long life, of 99 years, 8 months, and 18 days.[41]

Rudis

An arena referee or his assistants, named after the wooden staff (rudis) used to direct or separate combatants. A senior referee or trainer was known as a summa (high) rudis.[42][43]

Venator

The venator ("hunter") specialized in wild animal hunts instead of fighting them as the bestiarii did. As well as hunting they also performed tricks with animals such as putting an arm in a lion's mouth, riding a camel while leading lions on a leash, and making an elephant walk a tightrope.[44]

References

- ↑ Stephen Wisdom Gladiators 100 BC-AD 200 Osprey Publishing, 2001 Pg 28–29 ISBN 978-1-84176-299-9

- ↑ Gladiators fought by the book New Scientist February 23, 2006

- ↑ Head injuries of Roman gladiators Forensic Science International Volume 160, Issue 2, Pages 207-216 July 13, 2006

- ↑ Roman gladiators were fat vegetarians ABC Science April 5, 2004

- ↑ Stephen Wisdom, Angus McBride, Gladiators: 100 BC - AD 200, Oxford, United Kingdom, Osprey. Author's sketch and note, p. 18.

- ↑ Cicero, Ad familiares 7.10.2 (=95), as cited by Piganiol, “Les trinci gauloises."

- ↑ cf the entry for andabata in the Oxford Latin Dictionary, and Xavier Delamarre's entry on andabata, in Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise (Éditions Errance, 2003), p. 46.

- 1 2 Duncan, Anne (2006). Performance and Identity in the Classical World. Cambridge University Press. p. 205.

- ↑ Fagan, Garret G. (2011). The Lure of the Arena: Social Psychology and the Crowd at the Roman Games. Cambridge University Press. p. 217.

- ↑ Carter, Michael (2001). "Artemidorus and the Arbelas Gladiator". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 134: 109–115. JSTOR 20190801. (subscription required)

- ↑ Alison Futrell, Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power (University of Texas Press, 1997), p. 34.

- ↑ Kyle, Donald G., Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World, Blackwell Publishing, 2007. p. 273 ISBN 0-631-22970-1

- ↑ Travis, Hilary John (2014-12-15). Roman Helmets. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781445638478 – via google.ca.

- ↑ Book III, 43, 46 in The Annals of Tacitus, Loeb, 1931 For possible misidentification, see note 8: "Since the Gauls despised body-armour, the phrase must refer only to the conventional equipment of the "Gallus" (murmillo)"

- 1 2 3 Marcus Junkelmann, 'Familia Gladiatoria: "The Heroes of the Amphitheatre"' in The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome: Gladiators and Caesars, ed. by Eckart Köhne and Cornelia Ewigleben (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2000), p. 63

- ↑ Junkelmann 2000, pp. 37 and 47-48

- ↑ Southon, Emma (2020). A Fatal Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum: Murder in Ancient Rome. New York City: Abrams. p. 166. ISBN 978-1-4197-5305-3.

- ↑ McCullough, Anna., “Female Gladiators in the Roman Empire”, in: Budin & Turfa (eds), Women in Antiquity: Real Women across the Ancient World, Routledge (2016), p. 958

- ↑ Junkelmann 2000, pp. 52-53

- ↑ Junkelmann 2000, pp. 48-51

- ↑ Rich, Anthony (1883). "Parmularius". Dictionnaire des Antiquités romaines et grecques.

- ↑ Daremberg, Charles; Saglio, E. (1877). "Gladiator". Le Dictionnaire des Antiquités grecques et romaines. p. XXII (Les partis).

- ↑ Junkelmann 2000, pp. 37 and 57-59. See the headstone of Anicetus for a provocator with spatha.

- ↑ Junkelmann 60–61.

- ↑ Junkelmann 2000, pp. 59-61

- ↑ F. R. D. Goodyear The Classical Papers of A. E. Housman:, Volume 2; Volumes 1897-1914 Cambridge University Press 2004 ISBN 9780521606967 Pg 621 - 622

- ↑ "The Retiarius Tunicatus of Suetonius, Juvenal, and Petronius" (1989) by Steven M. Cerutti and L. Richardson, Jr. The American Journal of Philology, 110, P589-594

- ↑ James Rouse The beauties and antiquities of the county of Sussex, 149 lithogr. views accompanied by historical and explanatory notices Oxford University 1825 Pg 284 - 285

- ↑ "Gladiators - The Language of the Arena - Archaeology Magazine Archive". archaeology.org.

- ↑ Junkelmann 2000, p. 37

- ↑

- Marcus Junkelmann, Das Spiel mit dem Tod. So kämpften Roms Gladiatoren. Mainz am Rhein, 2000, ISBN 3-8053-2563-0.

- ↑ Junkelmann 2000, pp. 40-41 and 61-63

- ↑ Junkelmann 2000, pp. 51-57

- ↑ Travis, Hilary; Travis, John (2014). Roman Helmets. Amberley Publishing. pp. 59–60, 68. ISBN 9781445638478.

- ↑ Versnel, Henk (1998). Inconsistencies in Greek and Roman Religion, Volume 1: Ter Unus. Isis, Dionysos, Hermes. Three Studies in Henotheism. Studies in Greek and Roman Religion. BRILL. p. 231. ISBN 9004296727.

- ↑ Nossov, Konstantin (2011). Gladiator: The Complete Guide to Ancient Rome's Bloody Fighters. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0762777334.

- ↑ Luciana Jacobelli, Gladiators at Pompeii (Getty Publications, 2003), p. 19.

- ↑ Jacobelli, Gladiators at Pompeii, p. 19.

- ↑ Lawrence Keppie, "A Centurion of Legio Martia at Padova?" Journal of Roman Military Equipment Studies 2 (1991), as reprinted in Legions and Veterans: Roman Army Papers 1971–2000 (Steiner, 2000), p. 68.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann, "Familia Gladiatoria: The Heroes of the Amphitheatre," in Gladiators and Caesars: The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome (University of California Press, 2000), p. 63.

- ↑ Thomas E. J. Wiedemann, Emperors and Gladiators (Routledge, 1992, 1995), p. 121.

- ↑ Hubbard, Ben (2016). Gladiators. Conquerors and Combatants. Cavendish Square Publishing. pp. 189, 215. ISBN 9781502624574.

- ↑ Mañas, Alfonso (2011). Munera Gladiatoria: Origen del deporte espectáculo de masas (PDF) (PhD) (in Spanish). University of Granada. pp. 184, 186. ISBN 978-84-695-1026-1.

- ↑ Seneca, Ep. 85.41.