Pah Wongso | |

|---|---|

Pah Wongso in 1938, while raising funds to help China | |

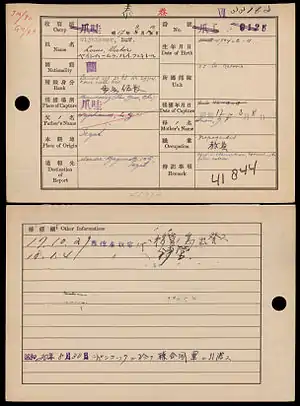

| Born | Louis Victor Wijnhamer 11 February 1904 |

| Died | 13 May 1975 (aged 71) Jakarta, Indonesia |

| Nationality | Indonesian |

| Occupation | Social worker |

Louis Victor Wijnhamer (11 February 1904 – 13 May 1975), better known as Pah Wongso (Chinese: 伯王梭; pinyin: Bó Wángsuō), was an Indo social worker popular within the ethnic Chinese community of the Dutch East Indies, and subsequently Indonesia. Educated in Semarang and Surabaya, Pah Wongso began his social work in the early 1930s, using traditional arts such as wayang golek to promote such causes as monogamy and abstinence. By 1938, he had established a school for the poor, and was raising money for the Red Cross to send aid to China.

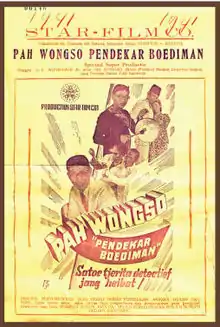

In late 1938, Pah Wongso used a legal defense fund, which had been raised for him when he was charged with extortion, in order to establish another school; this was followed by an employment center in 1939. In 1941, Star Film released two productions, Pah Wongso Pendekar Boediman and Pah Wongso Tersangka, starring him and featuring his name in the title. During the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies, Pah Wongso was held in a series of concentration camps in South-East Asia. He was repatriated after the War, and raised funds for the Red Cross and ran an employment office until his death.

Early life and social work

Louis Victor Wijnhamer was born on 11 February 1904 in Tegal, Central Java, in the Dutch East Indies.[1] One of three siblings, Wijnhamer was born to an ethnic Dutch administrator from Surabaya, Louis Gregorius Wijnhamer and J. F. Ihnen;[1][2] he was of Indo descent.[3] He studied at the senior high school in Semarang, before spending some time at the Suikerschool in Surabaya, later arriving in Batavia (now Jakarta). There, between 1927 and 1937, he worked as an amanuensis at the School tot Opleiding van Inlandsche Artsen.[2]

By the early 1930s, Wijnhamer, known as Pah Wongso,[lower-alpha 1] was recognised in West Java for his promotion of social causes. These included promoting monogamy and faith in Western medicine, as well as combating gambling and the use of opium and alcohol. In conveying his messages he often used the Sundanese wayang golek (a form of rod puppet), as the local people were generally unable to read. He was able to speak Dutch, Malay, and Javanese fluently, and had some command of Chinese and Japanese. This social work was funded predominantly from Pah Wongso's day job, selling fried peanuts (kacang goreng).[4][5]

By 1938 Pah Wongso had married and opened a school for poor children, particularly those of mixed Chinese descent, in Gang Patikee; it was funded by donations. He was also a member of the Indies branch of the Red Cross, and recognized for his humanitarian work.[5][6] He organised night fairs in various cities in the Indies (including in Yogyakarta, Semarang, and Surabaya), holding auctions and selling drinks and snacks in order to raise money to send aid to China, then fighting against the Japanese.[6]

Establishment of schools and popularity

After one of these fairs, in Yogyakarta, Pah Wongso was arrested for writing a threatening letter to Liem Tek Hien, who refused to pay f. 10 for a walking stick he said that he had not purchased, and held at Struiswijk Prison in Batavia.[6][7][8] He was charged with "attempted extortion and unpleasant treatment".[lower-alpha 2][9] The case was widely followed by ethnic Chinese in the Indies, and the newspaper Keng Po established a defense fund for Pah Wongso, which raised more than f. 1,300 by mid-June 1938; this had reached almost f. 2,000 by the end of the month.[9] The case was brought to trial on 24 June 1938. Although Liem regretted reporting Pah Wongso to the police, the prosecutor called for a two-month sentence, while the defence asked for an acquittal, or time served.[7][10][8]

Ultimately, on 28 June 1938 the judge gave a sentence of one month – equal to the time Pah Wongso had served – and he was released.[11] Pah Wongso appealed the court sentence, calling for an acquittal;[12] in August 1938 his sentence was reduced to a 25-cent fine.[13] The defense fund collected by Keng Po, totaling almost f. 3,500 by August, was allocated to the establishment of a school;[11] on 8 August 1938 the Pah Wongso Crèches school for impoverished youth opened at 20 Blandongan St. in Batavia.[14][15] By the end of the year Pah Wongso had participated in a march on opium use and been featured in a special issue of Fu Len.[16][17]

In 1939 Pah Wongso expanded his school in Blandongan to include an employment office. Established with f. 1,000, the office was located above the school and by November 1939 was training 22 job seekers. The Pah Wongso Crèches, meanwhile, served more than 200 ethnic Chinese and indigene students.[18] He continued speaking out against the working conditions in the Indies, giving a lecture to a 1,000-strong audience at the Queens Theatre in Batavia in October 1939. He remained highly popular with the ethnic Chinese.[19]

In 1941, Star Film made two films starring Pah Wongso to take advantage of his popularity. The first, Pah Wongso Pendekar Boediman (Pah Wongso the Cultured Warrior), depicted him as a nut seller who investigates the murder of a rich hajji.[20][21][22] It was released to popular acclaim, although the journalist Saeroen suggest this was predominantly because of Pah Wongso's existing popularity within the Chinese community.[23] A second film, a comedy titled Pah Wongso Tersangka, depicted Pah Wongso as a suspect in an investigation and was released in December 1941.[24] Writing in the magazine Pertjatoeran Doenia dan Film, "S." praised the introduction of comedy to the Indies' film industry, and expressed hope that the film would "leave audiences rolling with laughter".[lower-alpha 3][25]

Later life

In March 1942, the Empire of Japan occupied the Dutch East Indies. Pah Wongso was captured in Bandung on 8 March,[1] and spent three years in a series of concentration camps in South-East Asia, including in Thailand, Singapore and Malaya.[26] He returned to the Indies, now independent and known as Indonesia, by 1948, when he established the "Tulung Menulung" (literally "mutual assistance") social office;[27] he also worked for Bond Motors' Jakarta branch.[28] In the mid-1950s he met President Sukarno,[29] and by 1957 a biography of Pah Wongso was for sale.[30] He and his wife Gouw Tan Nio (also known as Leny Wijnhamer) had their fifth child on 3 February 1955.[31]

Pah Wongso continued to raise money for the Red Cross by selling fried peanuts.[32] He also continued to operate his school in Blandongan, as well as the employment office, which trained young men and women for positions such as maids, gardeners, and bellhops, then placed them with employers. Several of Pah Wongso's students came from islands other than Java. De Nieuwsgier gave the story of one young man, from Bengkulu, who had come to Java to study, been robbed of all his possessions while in Jakarta, then been helped by Pah Wongso to find work.[33]

Pah Wongso continued operating his school and employment office, under the auspices of the Pah Wongso Foundation, into the 1970s. He touted that the foundation had found positions for 1,000 young women and 11,000 young men,[15] and advertisements offering to place labourers were issued in Indonesian, English, and Dutch.[34] The institution also provided printing services; wrote letters on demand in English, Dutch, and Indonesian;[35] and provided wayang performances with four kinds of puppets.[36] Pah Wongso died in Jakarta on 13 May 1975.[28]

Explanatory notes

- ↑ In Javanese, the word wongso (Indonesian: bangsa) means "people" (Barnard 2010, p. 65).

- ↑ Original: "... poging tot afpersing en onaangename bejegening"

- ↑ Original: "membikin orang tertawa terpingkal-pingkal"

References

- 1 2 3 Registration card.

- 1 2 De Indische courant 1941, Wie.

- ↑ Barnard 2010, p. 65.

- ↑ Volk en Vaderland 1936.

- 1 2 Bataviaasch nieuwsblad 1938, Nieuws.

- 1 2 3 Bataviaasch nieuwsblad 1938, Pah Wongso.

- 1 2 Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië 1938, 'Pah Wongso'.

- 1 2 De Indische courant 1938, Pah Wongso voor den Rechter.

- 1 2 Bataviaasch nieuwsblad 1938, Pah Wongso voor den Politie-Rechter.

- ↑ De Sumatra post 1938, Tegen.

- 1 2 Bataviaasch nieuwsblad 1938, Zijn.

- ↑ De Indische courant 1938, Pah Wongso in Hooger Beroep.

- ↑ De Indische courant 1938, Pah Wongso Krijgt Minder Straf.

- ↑ Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië 1938, Pah Wongso Crèches.

- 1 2 Pah Wongso Foundation, (untitled advertisement 1), obverse, reverse.

- ↑ Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië 1938, Anti-Opium.

- ↑ De Indische courant 1938, Fu Len.

- ↑ Bataviaasch nieuwsblad 1939, Nieuw Tehuis.

- ↑ Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië 1939, Een Volksbijeenkomst.

- ↑ Biran 2009, p. 246.

- ↑ Filmindonesia.or.id, Pah Wongso.

- ↑ Bataviaasch nieuwsblad 1941, Pah Wongso.

- ↑ Biran 2009, p. 247.

- ↑ Pertjatoeran Doenia dan Film 1941, Tirai Terbentang.

- ↑ S. 1941, p. 15.

- ↑ Pah Wongso Foundation, (untitled advertisement 1), obverse.

- ↑ Pah Wongso Foundation, (untitled postcard 2).

- 1 2 KITLV, Inventory, p. 1.

- ↑ Pah Wongso Foundation, (untitled postcard 1).

- ↑ Java Bode 1957, Wie.

- ↑ De nieuwsgier 1955, Familieberichten.

- ↑ De nieuwsgier 1954, Boksen.

- ↑ De nieuwsgier 1954, Abdul.

- ↑ Pah Wongso Foundation, (untitled advertisement 2).

- ↑ Pah Wongso Foundation, (untitled advertisement 3).

- ↑ Pah Wongso Foundation, (untitled postcard 3).

Works cited

- "Abdul kwam uit Bengkulu, Pak Wongso in de Kota..." [Abdul came from Bengkulu, Pak Wongso in the City...]. De nieuwsgier (in Dutch). Jakarta. 26 June 1954. p. 2.

- "Anti-Opium Demonstratie" [Anti-Opium Demonstration]. Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië (in Dutch). Batavia. 3 October 1938. p. 6.

- Barnard, Timothy P. (February 2010). "Film Melayu: Nationalism, Modernity and Film in a pre-World War Two Malay Magazine". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. Singapore: McGraw-Hill Far Eastern Publishers. 41 (1): 47–70. doi:10.1017/S0022463409990257. ISSN 0022-4634. S2CID 162484792.

- Biran, Misbach Yusa (2009). Sejarah Film 1900–1950: Bikin Film di Jawa [History of Film 1900–1950: Making Films in Java] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Komunitas Bamboo working with the Jakarta Art Council. ISBN 978-979-3731-58-2.

- "Boksen en katjang-eten bij Pah Wongso" [Boxing and Nut Eating, from Pah Wongso]. De nieuwsgier (in Dutch). Jakarta. 1 November 1954. p. 2.

- "Een goed vaderlander Zijn werk in de kampongs Opvoeder van de inheemsche bevolking Wie is Pah Wongso en wal doet bij?" [A Good Patriot; A Worker in the Kampongs; An Educator of the Indigenes; Who is Pah Wongso and What are His Works?]. Volk en Vaderland (in Dutch). Utrecht. 27 November 1936. p. 3.

- "Een Volksbijeenkomst: Pah Wongso in het Queens-theater" [A People's Meeting: Pah Wongso at the Queens Theatre]. Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië (in Dutch). Batavia. 9 October 1939. p. 6.

- "Familieberichten" [Family News]. De nieuwsgier (in Dutch). Jakarta. 5 February 1955. p. 4.

- "'Fu Len' Pah Wongso Nummer" ['Fu Len': Pah Wongso Nummer]. De Indische courant (in Dutch). Batavia. 22 December 1938. p. 13.

- "KITLV-inventaris 202" [KITLV Inventory 202] (PDF) (in Dutch). KITLV. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- "Nieuw Tehuis van Pah Wongso Voor werkzoekende Chineesche jongelieden" [New Employment Office for Young Chinese by Pah Wongso]. Bataviaasch nieuwsblad (in Dutch). Batavia. 11 November 1939. p. 3.

- "Nieuws uit de Lampong Opening Pasar-malam te Telok" [News from the Lampong Opening of the Telok Night Fair]. Bataviaasch nieuwsblad (in Dutch). Batavia. 8 March 1938. p. 2.

- "Pah Wongso Crèches". Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië (in Dutch). Batavia. 6 August 1938. p. 6.

- "Pah Wongso gearresteerd" [Pah Wongso Arrested]. Bataviaasch nieuwsblad (in Dutch). Batavia. 30 May 1938. p. 2.

- "Pah Wongso in Hooger Beroep" [Pah Wongso in Appeal]. De Indische courant (in Dutch). Batavia. 6 July 1938. p. 6.

- "'Pah Wongso' Krijgt Minder Straf: In plaats van een maand, 25 cent boete" ['Pah Wongso' Gets a Lesser Punishment: Instead of a Month, a 25-Cent Fine]. De Indische courant (in Dutch). Batavia. 27 August 1938. p. 11.

- "Pah Wongso op de film" [Pah Wongso on Film]. Bataviaasch nieuwsblad (in Dutch). Batavia. 2 April 1941. p. 3.

- "Pah Wongso Pendekar Boediman". filmindonesia.or.id (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Konfidan Foundation. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- "'Pah Wongso' voor den Politie-Rechter" [Pah Wongso for the Police Court]. Bataviaasch nieuwsblad (in Dutch). Batavia. 16 June 1938. p. 3.

- "Pah Wongso voor den Rechter" [Pah Wongso for the Courts]. De Indische courant (in Dutch). Batavia. 25 June 1938. p. 9.

- "'Pah Wongso' was àl te Diligent! De Strafbare Brief aan een Chineesch Ingezetene te Jogja, die Bon van Tien Gulden niet wou Betalen Denk er om, dat Berouw steeds te Laat komt" ['Pah Wongso' was too diligent! The Criminal Letter to a Chinese Citizen of Yogyakarta, the Unpaid Ten-Gulden Bond, and the Thought that Repentance Always Comes Too Late]. Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië (in Dutch). Batavia. 24 June 1938. p. 5.

- Registration card, Government of Japan, 1942 – via National Archives of the Netherlands

- S. (October 1941). "Tidakkah Indonesia Dapat Mengadakan Film Loetjoe?" [Can't Indonesians Make Comedies?]. Pertjatoeran Doenia Dan Film (in Indonesian). Batavia: 14–15.

- "Tegen 'Pah Wongso' Twee Maanden Geëischt" [Two Months Demanded of Pah Wongso]. De Sumatra post (in Dutch). Padang. 24 June 1938. p. 3.

- "Tirai Terbentang" [Open Curtains]. Pertjatoeran Doenia Dan Film (in Indonesian). Batavia. 1 (7): 28–29. December 1941.

- (Untitled advertisement 1), Jakarta: Pah Wongso Foundation, 1970s – via the Lin Liu-hsin Puppet Theatre Museum

- (Untitled advertisement 2), Jakarta: Pah Wongso Foundation, 1970s – via the Lin Liu-hsin Puppet Theatre Museum

- (Untitled advertisement 3), Jakarta: Pah Wongso Foundation, 1970s – via the Lin Liu-hsin Puppet Theatre Museum

- (Untitled postcard 1), Jakarta: Pah Wongso Foundation, 1957 – via the Lin Liu-hsin Puppet Theatre Museum

- (Untitled postcard 2), Jakarta: Pah Wongso Foundation, 1970s – via the Lin Liu-hsin Puppet Theatre Museum

- (Untitled postcard 3), Jakarta: Pah Wongso Foundation, 1970s – via the Lin Liu-hsin Puppet Theatre Museum

- "Wie is Pah Wongso" [Who is Pah Wongso]. Java Bode (in Dutch). Jakarta. 14 August 1957. p. 3.

- "Wie was Pah Wongso" [Who was Pah Wongso]. De Indische courant (in Dutch). Batavia. 20 February 1941. p. 6.

- "Zijn straf al uitgezeten" [His Sentence Already Served]. Bataviaasch nieuwsblad (in Dutch). Utrecht. 28 June 1938. p. 3.

Further reading

External links

Media related to Pah Wongso at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pah Wongso at Wikimedia Commons- Media related to Pah Wongso at the Lin Liu-hsin Puppet Theatre Museum (via Facebook)

- The former employment office, on Google Street View

- Media related to Pah Wongso in the Dutch Royal Library.