Quilombo dos Palmares or Angola Janga | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1605–1694 | |||||||||

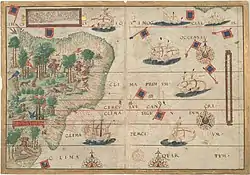

.jpg.webp) Southern part of the Captaincy of Pernambuco, in modern-day state of Alagoas, with representation of the Quilombo dos Palmares | |||||||||

| Status | Quilombo | ||||||||

| Capital | Serra da Barriga, today in Alagoas, Brazil | ||||||||

| Common languages | Bantu languages, Portuguese, Indigenous languages | ||||||||

| Religion | Afro-American religions, Kongo religion, Catholicism and Animism, maybe Islam, Protestantism and Judaism minorities | ||||||||

| Government | Confederated monarchy | ||||||||

• c.1670-1678 | Ganga Zumba (first confirmed) | ||||||||

• 1678 | Ganga Zona | ||||||||

• 1678–1694 | Zumbi (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Colonial Brazil | ||||||||

• Runaway African slaves found the settlement on Serra da Barriga | 1605 | ||||||||

• Bandeirantes destroy the last fortress (resistance in the region goes until 1790) | 1694 | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1690 | 11,000[1] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Brazil |

|---|

|

|

|

Palmares, or Quilombo dos Palmares, was a quilombo, a community of escaped slaves and others, in colonial Brazil that developed from 1605 until its suppression in 1694. It was located in the captaincy of Pernambuco, in what is today the Brazilian state of Alagoas. The quilombo was located in what is now the municipality of União dos Palmares.[2]

Background

The modern tradition has been to call the community the Quilombo of Palmares. Quilombos were settlements mainly of survivors and free-born enslaved African people. The quilombos came into existence when Africans began arriving in Brazil in the mid-1530s and grew significantly as slavery expanded.

No contemporary document called Palmares a quilombo; instead the term mocambo was used.[3] Palmares was home to not only escaped enslaved Africans, but also to Indigenous peoples, caboclos, and poor or marginalized Portuguese settlers, especially Portuguese soldiers trying to escape forced military service.[4]

Overview

One estimate places the population of Palmares in the 1690s at around 20,000 inhabitants,[5] although recent scholarship has questioned whether this figure is exaggerated. Stuart Schwartz places the number at roughly 11,000, noting that it was, regardless, "undoubtedly the largest fugitive community to have existed in Brazil".[1] These inhabitants developed a society and government that derived from a range of Central African sociopolitical models, a reflection of the diverse ethnic origins of its inhabitants, although Schwartz emphasizes that the residents of Palmares "combined these [sociopolitical models] with aspects of European culture and specifically local adaptations."[6] This government was confederate in nature, and was led by an elected chief who allocated landholdings, appointed officials (usually family members), and resided in a type of fortification called Macoco. Six Portuguese expeditions tried to conquer Palmares between 1680 and 1686, but failed. Finally the governor of the captaincy of Pernambuco, Pedro Almeida, organized an army under the leadership of the Bandeirantes Domingos Jorge Velho and Bernardo Vieira de Melo and defeated a palmarista force, putting an end to the republic in 1694.[7]

Formative period (1620–53)

Palmares was the general name given by the Portuguese in Pernambuco and Alagoas to the interior districts beyond the settlements on the coast, especially the mountain ranges, because there were many palm trees there. As early as 1602, Portuguese settlers complained to the government that their captives were running away into this inaccessible region and building mocambos, or small communities. However, the Portuguese were unable to dislodge these communities, which were probably small and scattered, and so expeditions continued periodically into the interior.

During this time the vast majority of the enslaved Africans who were brought to Pernambuco were from Portuguese Angola, perhaps as many as 90%, and therefore it is no surprise that tradition, reported as early as 1671 related that its first founders were Angolan. This large number was primarily because the Portuguese used the colony of Angola as a major raiding base, and there was a close relationship between the holders of the contract of Angola, the governors of Angola, and the governors of Pernambuco.

In 1630 the Dutch West India Company sent a fleet to conquer Pernambuco, in the context of the Dutch-Portuguese War, during the period of the Iberian Union. Although they captured and held the city of Recife, they were unable (and generally unwilling) to conquer the rest of the province. As a result, there was a constant low-intensity war between Dutch and Portuguese settlers. During this time thousands of enslaved people escaped and went to the Palmares.

Although initially the Dutch considered making an alliance with Palmares against the Portuguese, peace agreements put them in the position of supporting the sugar plantation economy of Pernambuco. Consequently, the Dutch leader John Maurice of Nassau decided to send expeditions against Palmares. These expeditions also collected intelligence about them, and it is from these accounts that we learn about the organization of Palmares in their time.

By the 1640s, many of the mocambos had consolidated into larger entities ruled by kings. Dutch descriptions by Caspar Barlaeus (published 1647) and Johan Nieuhof (published 1682) spoke of two larger consolidated entities, "Great Palmares" and "Little Palmares". In each of these units there was a large central town that was fortified and held 5,000-6,000 people. The surrounding hills and valleys were filled with many more mocambos of 50 to 100 people. A description of the visit of Johan Blaer to one of the larger mocambos in 1645 (which had been abandoned) revealed that there were 220 buildings in the community, a church, four smithies, and a council house. Churches were common in Palmares partly because Angolans were frequently Christianized, either from the Portuguese colony or from the Kingdom of Kongo, which was a Christianized country at that time. Others had been converted to Christianity while enslaved. According to the Dutch, they used a local person who knew something of the church as a priest, though they did not think he practiced the religion in its usual form.[8] Schwartz notes that African religious practices were also preserved and suggests that the depiction of Palmares as a largely Christian settlement is perhaps reflective of confusion or bias on the part of contemporary commentators.[6]

From Palmares to Angola Janga

After 1654 the Dutch were expelled, and the Portuguese began organizing expeditions against the mocambos of Palmares. In the post-Iberian Union period (after 1640), the kingdoms of Palmares grew and became even more consolidated. Two descriptions, one an anonymous account called "Relação das Guerras de Palmares" (1678) (Account of the war of Palmares), the other written by Manuel Injosa (1677), describe a large consolidated entity with nine major settlements and many smaller ones. Slightly later accounts tell us that the kingdom was named "Angola Janga" which according to the Portuguese meant "Little Angola," although this is not a direct translation from a Kimbundu term as one might expect. The two texts agree that it was ruled by a king, which the "Relação das Guerras" named "Ganga Zumba" and that members of his family ruled other settlements, suggesting an incipient royal family. He also had officials and judges as well as a more or less standing army.

Although the "Guerra de Palmares" consistently calls the king Ganga Zumba, and translates his name as "Great Lord" other documents, including a letter addressed to the king written in 1678 refer to him as "Ganazumba" (which is consistent with a Kimbundu term ngana meaning "lord"). One other official, Gana Zona also had this element in his name.

After a particularly devastating attack by the captain Fernão Carrilho in 1676-7 that wounded Zumba and led to the capture of some of his children and grandchildren, Ganga Zumba sent a letter to the Governor of Pernambuco asking for peace. The governor responded by agreeing to pardon Ganga Zumba and all his followers, on condition that they move to a position closer to the Portuguese settlements and return all enslaved Africans that had not been born in Palmares. Although Ganga Zumba agreed to the terms, one of his more powerful leaders, Zumbi refused to accept the terms. According to a deposition made in 1692 by a Portuguese priest, Zumbi was born in Palmares in 1655, but was captured by Portuguese forces in a raid while still an infant. He was raised by the priest, and taught to read and write Portuguese and Latin. At the age of 15, however, Zumbi escaped and returned to Palmares. There he quickly won a reputation for military skill and bravery and was promoted to the leader of a large mocambo.

In a short time, Zumbi had organized a rebellion against Ganga Zumba, who was styled as his uncle, and poisoned him (though this is not proven, and many believe Zumba poisoned himself as a warning not to trust the Portuguese). It is argued that Zumba was sick of fighting, but even more wary of signing the deal with the Portuguese, foreseeing their betrayal, and renewed war. By 1679 the Portuguese were again sending military expeditions against Zumbi. Meanwhile, the sugar planters reneged on the agreement and re-enslaved many of Ganga Zumba's followers who had moved closer to the coast.

From 1680 to 1694, the Portuguese and Zumbi, now the new king of Angola Janga, waged an almost constant war. The Portuguese government finally brought in the famed Portuguese military commanders Domingos Jorge Velho and Bernardo Vieira de Melo, who had made their reputation fighting indigenous peoples in São Paulo and then in the São Francisco valley. These men enlisted existing Pernambuco forces and local indigenous allies, who proved instrumental in the campaign. The final assault against Palmares occurred in January 1694. Cerca do Macaco, the main settlement, fell; accounts suggest a bitter fight that saw 200 inhabitants of Palmares kill themselves rather than surrender and face re-enslavement.[6] Zumbi was wounded. He eluded the Portuguese, but was betrayed, finally captured, and beheaded on November 20, 1695.

Zumbi's brother continued the resistance, but Palmares was ultimately destroyed, and Velho and his followers were given land grants in the territory of Angola Janga, which they occupied as a means of keeping the kingdom from being reconstituted. Palmares had been destroyed by a large army of Indians under the command of white and caboclo (white/Indian mixed-bloods) captains-of-war.[9]

Although the kingdom was destroyed the Palmares region continued to host many smaller runaway settlements, but there was no longer the centralized state in the mountains.

Fighting techniques

Although it is often argued that the inhabitants of Palmares defended themselves using the martial art form called capoeira, there is no documentary evidence that the residents of Palmares actually used this method of fighting.[10] Most accounts describe them as armed with spears, bows, arrows and guns.[11] They were able to acquire guns by trading with the Portuguese and by allowing small-holding cattle raisers to use their land. Guerrilla warfare was common; the inhabitants of Palmares, familiar with the terrain, marshaled camouflage and surprise attacks to their advantage. Fortifications of the Palmares encampments themselves included fences, walls, and traps.[6]

Historiography

In his article "Rethinking Palmares: Slave Resistance in Colonial Brazil," Schwartz challenges somewhat the historiographical conception of Palmares as a straightforward transposition of Angolan culture and sociopolitical structures, writing, "Much of what passed for African 'ethnicity' in Brazil were colonial creations. Categories or groupings such as 'Congo' or 'Angola' had no ethnic content in themselves and often combined peoples drawn from broad areas of African who before enslavement had shared little sense of relationship or identity." Instead, he characterizes Palmares as a hybrid society combining traditions of various African groups. He traces the etymology of the word quilombo to the ki-lombo, a circumcision camp common among the Mbundu people of Angola that served to forge cultural unity among disparate local ethnic groups, and argues that this practice might have informed the diversity of Palmares. He also notes class stratification within the quilombo; those kidnapped in raids were often enslaved by the people of Palmares. He further highlights an economic interdependence between the inhabitants of Palmares and white Portuguese living nearby, manifested in the regular exchange of goods.[6]

Historian Alida C. Metcalf cites recent archeological discoveries at the site of Palmares that "reveal extensive Indian influence" to argue for an "image of the community as one formed by both Indians and Africans seeking freedom."[12]

In movies

A semi-fictional account of Palmares was made into the 1984 Brazilian film by Carlos Diegues, Quilombo.

See also

- Atlantic slave trade

- Creole

- Dandara, female warrior and wife of Zumbi

- Zumbi

Notes

- 1 2 Stuart Schwartz, Slaves, Peasants and Rebels: Reconsidering Brazilian Slavery (Illinois, 1994), p. 121.

- ↑ Nicolette, Carlos Eduardo. Material Didático: O Quilombo dos Palmares Archived 2022-04-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Jane Landers. "Leadership and Authority in Maroon Settlements in Spanish America and Brazil." in Africa and the Americas: Interconnections During the Slave Trade. José C. Curto and Renée Soulodre-LaFrance, eds. 2005. p. 178fn31 (p. 183–184) ISBN 9781592212729.

- ↑ Africans in Brazil Archived 2007-07-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Orser, Charles E.; Funari, Pedro P.A. (January 2001). "Archaeology and slave resistance and rebellion". World Archaeology. 33 (1): 61–72. doi:10.1080/00438240126646. ISSN 0043-8243. S2CID 162409042.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Schwartz, Stuart (2005-04-07), "Rethinking Palmares: Slave Resistance in Colonial Brazil", African American Studies Center, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.43121, ISBN 978-0-19-530173-1, retrieved 2020-12-08

- ↑ "Palmares", Britannica Online.

- ↑ John Thornton, "Les Etats de l'Angola et la formation de Palmares (Bresil)" Annales Histoire, Science Sociales, 63.4 (2008): 760–797.

- ↑ João José Reis & Flávio dos Santos Gomes, "Quilombo: Brazilian Maroons during slavery" Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, January 31, 2002, Cultural Survival Quarterly, Issue 25.4.

- ↑ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 290.

- ↑ Assunção 2002, pp. 44.

- ↑ Metcalf, Alida C. (2005). Go-betweens and the colonization of Brazil, 1500–1600 (1st ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-79622-6. OCLC 605091664.

Bibliography

- Pita, Sebastião da Rocha, História da América Portuguesa, Ed. Itatiaia, 1976.

- Edison Carneiro,O Quilombo dos Palmares (São Paulo, 1947, only edition with documentary appendix, and three subsequent editions).

- Décio Freitas, Palmares: Guerra dos escravos (Rio de Janeiro, 1973 and five subsequent editions).

- R. Kent, "Palmares: An African State in Brazil," Journal of African History.

- R. Anderson, "The Quilombo of Palmares: A New Overview of a Maroon State in Seventeenth-Century Brazil," Journal of Latin American Studies 28, no. 3 (October 1996): 545–566.

- Irene Diggs: "Zumbi and the Republic of Os Palmares". Phylon. 1953. Atlantic Clark University. Vol. 2 p. 62.

- "Palmares", Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 24 October 2007.

- Charles E. Chapman, The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 3, No. 1 (January 1918), pp. 29–32.

- Vincent Bakpetu Thompson. Africans of the Diaspora: The Evolution of African Consciousness and Leadership in the Americas (From Slavery to the 1920s). Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2000. pp. 39–44.

- Glenn Alan Cheney, Quilombo dos Palmares: Brazil's Lost Nation of Fugitive Slaves, Hanover, CT:New London Librarium, 2014.

- Assunção, Matthias Röhrig (2002). Capoeira: The History of an Afro-Brazilian Martial Art. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-8086-6.

- Taylor, Gerard (2007). Capoeira: The Jogo de Angola from Luanda to Cyberspace. Vol. 1. Berkeley, CA: Blue Snake Books. ISBN 9781583941836.

- Desch-Obi, Thomas J. (2008). Fighting for Honor: The History of African Martial Art Traditions in the Atlantic World. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-718-4.