Palmetto Leaves is a memoir and travel guide written by Harriet Beecher Stowe about her winters in the town of Mandarin, Florida, published in 1873. Already famous for having written Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852), Stowe came to Florida after the U.S. Civil War (1861–1865). She purchased a plantation near Jacksonville as a place for her son to recover from the injuries he had received as a Union soldier and to make a new start in life. After visiting him, she became so enamored with the region she purchased a cottage and orange grove for herself and wintered there until 1884, even though the plantation failed within its first year. Parts of Palmetto Leaves appeared in a newspaper published by Stowe's brother, as a series of letters and essays about life in northeast Florida.

Scion of New England clergy, Stowe keenly felt a sense of Christian responsibility that was expressed in her letters. She considered it her duty to help improve the lives of newly emancipated blacks and detailed her efforts to establish a school and church in Mandarin toward these ends. Parts of the book relate the lives of local African-Americans and the customs of their society. Stowe described the charm of the region and its generally moderate climate but warned readers of "excessive" heat in the summer months and occasional cold snaps in winter. Her audience comprises relatives, friends, and strangers in New England who ask her advice about whether or not to move to Florida, which at the time was still mostly wilderness. Although it is a minor work in Stowe's oeuvre, Palmetto Leaves was one of the first travel guides written about Florida and stimulated Florida's first boom of tourism and residential development in the 1880s.

Background

Stowe buys an estate

By the time Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–1896) moved to Florida in 1867, she was already internationally famous for authoring Uncle Tom's Cabin, published as a serial between 1851 and 1852. The novel expounded upon her abolitionist views and was extraordinarily influential in condemning slavery in the United States. Stowe's opposition to slavery sprang from a moral passion based on her Christian faith. She had grown up the daughter of a Presbyterian minister, Lyman Beecher; seven of her brothers became ministers in Calvinist or Congregational denominations, and she married a minister.[1]

In 1860, Stowe's son Frederick "Fred" William Stowe enlisted in the First Massachusetts Infantry Regiment when Abraham Lincoln called for volunteers in anticipation of the Civil War. Much beloved, yet troubled, Fred Stowe had developed a problem with alcohol as early as sixteen. He took to army life, however, and was promoted to lieutenant. After receiving a head wound at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863, he endured severe headaches and was forced to resign his commission.[2] His alcoholism worsened, and he may have compounded it with a liberal use of opiates and narcotics, which were widely available.[3][4]

In 1866, Fred encountered two young farmers in Connecticut who had spent time on duty as Union soldiers in Florida during the war. He learned from them that land there was plentiful and cheap, and many recently emancipated blacks were available at low wages to work it. When he shared this information with his mother, Stowe and her husband Calvin Ellis Stowe considered it a prime opportunity to hasten their son's rehabilitation.[5] For $10,000 ($153,500 in 2009) she purchased a cotton plantation near Orange Park, south of Jacksonville, named Laurel Grove, that was originally established by slave trader Zephaniah Kingsley in 1803 and managed in part by his African wife, Anna Madgigine Jai, until 1811.[6][note 1]

Stowe intended that Fred would manage the estate as he recovered from his wounds and addictions. As an extension of her abolitionist ideals, she wrote to her brother Charles Beecher, however, about her potential role in the endeavor:

My plan ... is not in any sense a mere worldly enterprise. I have for many years had a longing to be more immediately doing Christ's work on earth. My heart is with that poor people whose cause in words I have tried to plead, and who now, ignorant and docile, are just in that formative state in which whoever seizes has them.

Corrupt politicians are already beginning to speculate on them as possible capital for their schemes and to fill their poor heads with all sorts of vagaries. Florida is the State into which they have, more than anywhere else, been pouring. Emigration is positively and decidedly setting that way; but as yet it is mere worldly emigration, with the hope of making money, nothing more.[7]

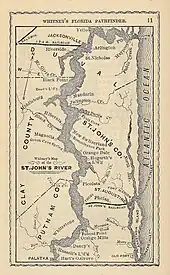

Charles Stowe, her son, later wrote that his mother searched for higher purpose in everything she did, from growing potatoes to writing. She wrote that the prospect of setting up a series of churches along the St. Johns River would be the best way to train former slaves, remarking "I long to be at this work and cannot think of it without my heart burning within me".[8][9][note 2] Florida was little populated and developed: it had just a fraction of the population of Georgia and Alabama. South of Ocala, approximately two people lived per square mile.[10]

Florida's school system was in disarray at the end of the Civil War; in 1866 a Northerner named A. E. Kinne noted there were fewer schools for white children than freedmen's schools for black children.[11] In 1860, there were no official schools for black children and slaves were prohibited from any education. At the same time, there were 97 public schools for white children and 40 private academies for them, some of which appeared to get public funding. In May 1865, the total Florida population was 154,000, and an estimated 47% of it was black, almost all of whom were former slaves.[12] A difference in attitudes about education between the races was apparent as freed blacks saw education as the key to increasing their opportunities, or at least escaping conditions they had endured during servitude.[11]

Transformation and failure

In the late winter of 1867, Stowe followed her son to Florida, finding that the warmer weather allowed her to spend more time on two novels she was writing. Her first weeks in Orange Park utterly transformed her and she became enchanted with Florida at once,[13] writing that she felt she had sprouted wings and become "young & frisky".[14] She accompanied her son one day to collect the mail, which was deposited in Mandarin, about 3 miles (4.8 km) across the St. Johns River. They rowed to the eastern shore and Stowe fell in love with a cottage in Mandarin, attached to an orange grove. Stowe's transformation in Florida was rooted in her identification and familiarity with Puritan New England: industry and thrift in a climate where cold sharpened one's senses and values. The laid-back attitude of the people and warmth of the Southern climate were seductive. She at first attempted to persuade her brother Charles to purchase the land in Mandarin, writing to him and asking "How do you think New England theology would have fared had been landed here instead of Plymouth Rock?"[1] She wrote about the land and climate intoxicating her and pondered the effect it might have had on literature when she posed an idea to her publisher: "I hate to leave my calm isle of Patmos—where the world is not and I have such quiet long hours for writing. [Ralph Waldo] Emerson could insulate himself here and keep his electricity. [Nathaniel] Hawthorne ought to have lived in an orange grove in Florida."[15]

Within a year, Laurel Grove failed. Fred was inexperienced and made poor bargains with local merchants. Before the war, plantations had been largely self-sufficient, but Fred paid high prices for goods shipped in from Savannah and Charleston. He took days off at a time to visit saloons in Jacksonville. An unanticipated infestation of cotton-worm larvae (Helicoverpa zea) destroyed much of the cotton crop. Only two bales were produced by Laurel Grove; Stowe realized the venture was a failure. Fred committed himself to a rehabilitation asylum in New York,[note 3][16][17] and at some point in 1867, Stowe purchased the cottage and the attached grove in Mandarin.

Citrus was distributed primarily in a regional market and was a luxury in northern cities; oranges in New York sold for about 50 cents per fruit.[18] The acreage attached to the house Stowe purchased could produce an income of $2,000 a month ($30,700 in 2009). Stowe wrote to author George Eliot to update her on the progress of improvements to the house in Mandarin, putting up wallpaper, improving plaster, and building a veranda that wrapped around the structure. She took pains not to disturb a giant oak and instead built the veranda around the tree. The house could accommodate as many as 17 family members and friends.[19]

From 1868 to 1884, Stowe split her time between her residence in Hartford, Connecticut, a mansion named Oakholm, and her house in Mandarin. A few weeks before Christmas each year, she would oversee arrangements to close Oakholm for the season, which involved preparing the house for the winter, packing all their clothes, living necessities, her writing materials, and the carpets in the house and shipping everything to Florida. Various family members would accompany her, living in the comfortable two-story house she modestly called a "cottage" or "hut".[20] In Hartford she was barraged with requests and at the center of a whirl of activity. Mandarin was not connected to a telegraph line until the 1880s and mail was received only once a week by boat. Stowe was able to relax somewhat in Mandarin and write for at least three hours a day.[21]

Description of text and publication

Stowe remained active, attending speaking engagements, writing, traveling frequently and publishing several novels while she was wintering in Mandarin. Though she promised her publishers, J. R. Osgood, another novel, she instead compiled a series of articles about Florida and letters to relatives in New England about her daily life. Some of them were first published in Christian Union, a local New England newspaper established by her brother Henry Ward Beecher.[22] In all, twenty chapters make up Palmetto Leaves that vary in tone depending upon Stowe's audience. "Buying land in Florida", "Florida for Invalids", and "Our Experience in Crops" are addressed more to general readers who may be considering moving to the region. Some essays are directed to describing the best sights in the area, such as "Flowery January in Florida", "Picnicking up Julington", "The Grand Tour up River", and "St. Augustine". A more personal touch is included in chapters entitled "A Letter to the Girls", "Letter-Writing", and "Our Neighbor Over the Way" as Stowe includes intimate details about her daily life in Mandarin. Her observations of the state and characteristics of emancipated slaves are mentioned intermittently in letters and essays, but the final two chapters, "Old Cudjo and The Angel" and "Laborers of The South", are dedicated solely to this topic.[23]

Palmetto Leaves was not Stowe's first travel memoir. In 1854 she published Sunny Memoirs of Foreign Lands about her first trip to Europe, a book unique as an American woman's view of Europe.[24] She followed this with Agnes of Sorrento that appeared as a serial in The Atlantic Monthly from 1861 to 1862. Source material for Agnes of Sorrento was culled from her observations of and experiences in Italy, collected during her third trip to Europe, which she took with her family. Olav Thulesius, author of Harriet Beecher Stowe in Florida, recognizes Stowe's tendency to spin everything she saw into something selectively positive. Stowe addressed this in the foreword to Sunny Memoirs of Foreign Lands, writing:

If the criticism be made that every thing is given couleur de rose, the answer is, Why not? If there be characters and scenes that seem drawn with too bright a pencil, the reader will consider that, after all, there are many worse sins than disposition to think and speak well of one's neighbors.

The object of publishing these letters is, therefore, to give to those who are true-hearted and honest the same agreeable picture of life and manners which met the writer's own eyes.[22]

Because little was known about the region, the elements of its climate, citrus, water, and general ideas about illness and health, Stowe was possibly first among several authors and advertising schemes that portrayed Florida as an exotic place of natural wonders and powers that could rejuvenate frail health. What travel writers published on Florida were exaggerated claims, readily accepted by audiences hungry for escapist literature.[25] Biographer Forrest Wilson considers the finished product, Palmetto Leaves—published in 1873—to be the first promotional writing about Florida ever. Occasionally letters about the state were printed in local newspapers in the North, but because Florida was still very much a rugged wilderness, Northerners really had no concept of what the region was like.[26] Rather besotted with the marvelous properties she saw in the orange, Stowe intended to call the book Orange Blossoms, but changed the title to better express the plant that proliferated the region the most.[22]

Subject and themes

Duty and calling

In the first chapter of Palmetto Leaves, Stowe tells how she takes a steamer to Savannah, Georgia. On board is a stray dog who begs scraps of food and affection from the passengers. It finally becomes attached to a woman on board and follows her around. At Savannah, the dog is thrown into the street by the porters and waiters at the hotel, and is eventually left behind. Stowe compares the dog and the people who care for such stray animals to Christian ideals to take care of the poor and suffering.[27]

The impressive orange tree served as a metaphor for Stowe in Palmetto Leaves. She calls it "the fairest, the noblest, the most generous, it is the most surprising and abundant of all trees which the Lord God caused to grow eastward in Eden", and compares it to her task of educating emancipated slaves.[28] When she first arrived in Mandarin, from 1868 to 1870, religious services were held in the Stowes' home, with Calvin presiding and Stowe teaching Sunday School to both black and white children and sometimes serving as an acolyte during services.[1] Stowe purchased a lot in 1869 to build a church for her neighbors that would double as a school to educate children, freed slaves, and anyone eager to learn. Though she encountered considerable frustration in dealing with the bureaucracy of the Freedmen's Bureau, construction was finished within a year and a teacher was in place, procured from Brooklyn, New York.[29] Stowe had an organ that was rolled from her home to the church, but after it became too difficult to roll back and forth, they locked it in a closet in the school. The building burned down to Stowe's deep dismay, probably because of some drifters who spent the night in it and caught the southern pine wood on fire from carelessness, although Olav Thulesius suggests it was arson committed by Stowe's neighbors who did not appreciate her efforts to educate black children.[30] After a frost in 1835, the orange trees in north Florida were killed, even underground, but they sprouted back only to be assaulted by insects, yet they recovered. While her neighbors helped to raise funds to rebuild the church, Stowe and the small community handed spellers to local blacks who were eager to learn. She decried the delay in the children's education: "To see people who are willing and anxious to be taught growing up in ignorance is the sorest sight that can afflict one".[31]

Florida and daily life in Mandarin

The entrance of the St. Johns from the ocean is one of the most singular and impressive passages of scenery that we ever passed through: in fine weather the sight is magnificent. —Harriet Beecher Stowe: Palmetto Leaves, p. 15

From her first sight of Florida, Stowe was greatly impressed. In Palmetto Leaves, she sings the praises of Florida in January as a beautiful land capable of producing superior citrus and flowers. In several letters Stowe describes the abundant plant life in the area, dedicating a chapter to yellow jessmines (Gelsemium sempervirens)[32] and another to magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora)[33] flowers. She details watching sugarcane pressed into sugar crystals, going visiting with her elderly and obstinate mule named Fly, and discovering the myriad things to find in the woods and what can be made of them. She also keeps a cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) in a cage and four cats,[34] but sadly reports later in the year that all four cats have died, to the relief and joy of Phœbus the cardinal.[35]

Stowe attempts to disabuse readers of the notion that the region is perfect. She writes, "In New England Nature is an up-and-down smart, decisive, housemother that has her times and seasons and brings up her ends of life with a positive jerk" and contrasts that characterization with Nature in Florida, an "indulgent old grandmother, who has no particular time for any thing and does every thing when she happens to feel like it".[36] Those who wish to live in Florida, Stowe warns, must also get to know its deficiencies: occasional freezing weather in winter, unsculptable lawns, insects and snakes, and people who disagree as they do everywhere else. Were Florida a woman, Stowe writes, she would be a dark brunette, full of jolly untidiness.[37] Malaria is a fact of life, and Stowe cautions Northerners who may be lured to the region by tales of the mild climate to understand that temperature extremes are common, taking particular effort to address consumptives, or those afflicted with tuberculosis. Those who consider moving to the region should weigh all these issues before making their decisions.[38] In The Journal of Southern History, Susan Eacker attests that Stowe's assignment of female characteristics to Florida coincided with her own gradual admission that she may be turning into a "woman's rights woman".[25]

Stowe recounts several sailing trips she takes on the St. Johns and Julington Creek and the animals she sees during her excursion, appreciating the alligators, "water-turkeys" (Anhinga anhinga), and "fish-hawks", or ospreys (Pandion haliaetus). Long an animal lover, she took her dogs, cats, and birds with her as part of the "earthquake" of the annual relocation from Hartford to Mandarin. She extended this care to other animals as well. In Naples, Italy, she once got out of a carriage to walk as it was being pulled up a steep hill by two beleaguered horses that were being whipped by the driver, and asked her companions and guide to do the same.[39] Not only did she write the first travel guide to Florida, but Stowe also became the first defender of wild animals. She pays particular attention in Palmetto Leaves to hunters who shoot at anything they see. Not taking offense at hunting for the sake of eating, Stowe laments killing for its own sake: "it must be something that enjoys and can suffer; something that loves life, and must lose it".[40] In 1877 she followed her book with a pamphlet that urged the cessation of the slaughter of Florida's wading birds, whose feathers were selling at the price of gold and used in women's hats.

Emancipated slaves

The final two letters in Palmetto Leaves address the newly freed slaves in Florida. Two strong women who are less docile than Stowe is accustomed are included. One, a field hand turned domestic named Minnah, whom Stowe has tried in vain to teach how to do household chores, is so forthright in her speech that Stowe writes, "Democracy never assumes a more rampant form than in some of these old negresses, who would say their screed to the king on his throne if they died for it the next minute. Accordingly, Minnah's back was marked and scored with the tyrant's answers to free speech."[41] Minnah eventually returns happily to the fields. Another, Judy, is complacent and enjoys taking mornings and afternoons off to see to her husband. Stowe attributes their work ethic to poor training and "the negligent habits inducted by slavery"; the truly talented and hard-working black laborers had moved on from homesteads to industry, able to demand their own price for their labors.[42]

Although Stowe describes Minnah and Judy with some tempered exasperation, she praises a riverboat stewardess named Commodore Rose. Once a slave owned by the captain, Rose had since been freed for saving his life during a boating accident and continues to work for him following emancipation. She is as forthright as Minnah and Judy, but Rose knows every portion of the river as well as the houses and sites along the banks, and their histories. Her knowledge of the ship and its guests is unparalleled, and all the crew and guests revere her opinion in all matters.[43]

In another story, Stowe and Calvin meet a man on a Mandarin dock who has been cheated out of much the land he was given by the government. Named Old Cudjo, he worked the small homestead on which he grew cotton for years. Where at first the neighbors surrounding the colony of former slaves from South Carolina were hesitant and suspicious, Old Cudjo and his colony were so industrious and honest that they won their white neighbors over. One who was a justice of the peace intervened on his behalf and Old Cudjo's land was returned to him.[44] Stowe's final chapter is dedicated to defending the notion that blacks should be employed to help build the state of Florida to transform it from a wilderness into a civilization. They are better suited for work in the hot sun, more resistant to malaria, and are trustworthy and extremely eager to learn. She also dedicates a few pages to her interested observations on their culture as she details overhearing their festivities at night and sitting outside an informal church service.[45]

Reception and criticism

Palmetto Leaves became a best-seller for Stowe and was released in several editions. It was published again in 1968 as part of Bicentennial Floridiana, a series of original facsimile texts about the history of the state. It was so popular that through publishing it, Stowe virtually ruined the peace and quiet she sought in Mandarin to be able to work. The year following the publication of Palmetto Leaves, Stowe reported that 14,000 tourists had visited North Florida.[26] Two years after its initial publication, a writer working for Harper's magazine noted that Stowe was "besieged by hundreds of visitors, who do not seem to understand that she is not an exhibition".[46]

Stowe's house, which was located on the bank of the St. Johns River, became a tourist attraction, as riverboats shuffling tourists from Jacksonville to Palatka or Green Cove Springs passed close by and slowed, so the captains could point out her home to their clients. Eventually a dock was built so that visitors could come ashore and peek into the windows of the home.[47] One, who dared to pull down a tree branch covered with orange blossoms in full bloom over the Stowe's veranda, was chased off the property by Calvin. Local residents who held Stowe in less than high regard insinuated that she worked with the enterprising riverboat captains to pose for tourists.[48]

Stowe was among several authors who wrote about Florida following the Civil War. By far, the majority were men who concentrated on hunting prospects, but the women who wrote about the region often used an adolescent narrator who was usually male as a device to describe their encounters with the novelty of what they saw.[25] Stowe wrote simply as herself, something that may have been allowed because of her celebrity. Gene Burnett, author of Florida's Past: People and Events That Shaped the State writes:

Harriet was probably never fully aware of how great had been her influence in advertising Florida to the country, turning it from an obscure down under tip on the map into a beckoning, lush, tropical paradise, to which tens of thousands would flock to help build a state over the following decades. She herself would doubtless have viewed it as a fitting Christian act to help restore a prostrate, defeated brotherland to its feet; Florida's first promoter was merely a Good Samaritan.[48]

Uncle Tom's Cabin was clearly Stowe's magnum opus (although she considered Old Town Folks, which was written while she was in Mandarin, to have that designation[25]), as Stowe family history recalls that Abraham Lincoln entertained the author during a visit to the White House, and greeted her by saying "So this is the little lady who made this big war?"[49] Compared to it, Palmetto Leaves is considered a minor work and is rarely included in the canon of criticism about Stowe's writings. The Cambridge Introduction to Literature series on Stowe addresses it briefly, however, noting that the mixed essay and letter format make it "uneven in quality and unstable in stance".[23] More assertive criticism was directed toward Stowe's portrayals of the local Mandarin blacks. Cambridge Introduction to Literature author Sarah Robbins called it "downright offensive" and declared that Stowe negated her own attempts to persuade her readers that emancipated slaves were industrious and could assist in rebuilding the South of their own volition by including unflattering descriptions of their physical features—comparing Old Cudjo to a baboon, for example—and writing that supervising and taking care of them was necessary.[23] Susan Eacker agrees, writing that Stowe's views were representative of the majority of white Americans' ideas of where blacks should be in the social scheme of the New South.[25]

Post-publication

The effects of Stowe's writings about Florida were duly noted by authorities. Her brother Charles purchased his own land upon her recommendation, not in Mandarin but in Newport near Tallahassee. During a visit to his home in 1874, she and a few Northern investors had an audience with Governor Marcellus Stearns. They were met by his cabinet and staff on the steps of the state capitol building—which was festooned with greenery and a large welcome sign for the occasion—and they gave Stowe a round of loud and exuberant cheers.[50]

In 1882 Stowe purchased a plot of land in Mandarin on the St. Johns to build the Mandarin Church of Our Saviour, the dedication of which she attended. The windows of the church were installed by its benefactors. Calvin's health began to fade and in 1884 the Stowe family left Mandarin forever to spend the rest of their years in Hartford. He died two years later and Stowe asked to add a window in the Mandarin church in his memory, but it remained plain glass for 30 years. The church's parishioners remained so loyal to Stowe that they neglected to suggest an alternate plan for the window.[51] Stowe declined into a childlike state after 1894, losing much of her memory but keeping her fascination with plants and flowers as she would wander Hartford exclaiming over those she came across.[52] She died in 1896.

A frost in 1886 killed much of the orange industry in Mandarin and the town saw an economic decline. In 1916, an ornate stained glass window constructed by Louis Comfort Tiffany was installed in the Church of Our Saviour, depicting a large oak tree overlooking the river. The church and Mandarin residents offered no more than $500 for the window; for three years ten cent subscriptions were raised around Mandarin, and notices were placed in New York magazines to solicit finances for it. Although scholars have stated that Stowe's efforts to educate local blacks were ultimately unsuccessful,[25] the woman who spearheaded the fundraising effort for the memorial window noted that the project was enthusiastically supported by local black churches and residents, who gave what they could out of affection for Stowe, remembering that she taught some of them to read. The window probably cost Tiffany $850 ($18,206 in 2009), and though there is no record of exactly how much Tiffany was paid, he took the project on because he liked the design: the tree, the moss, the Southern motif, and because it was to memorialize the Stowes. He probably made no profit from it.[51]

Beneath it read "In that hour, fairer than daylight dawning/ Remains the glorious thought, I am with Thee", part of a hymn penned by Stowe.[53][54] The school Stowe sponsored closed in 1929. Following Stowe's departure, the next owners of the house turned it into a lodge named after her. It closed in the 1940s and was subsequently replaced by a spacious home; what survives is the 500-year-old oak tree, which the Stowes built around instead of removing.[55] The oak had continued to grow and upset the foundation of the new home.[51]

The stained glass window became a tourist attraction and the last memorial to Stowe in Florida; in later decades some of the parishioners and clergy had doubts about its "churchliness" as it was a rare depiction in an Anglican church not referencing a Biblical theme.[56] In 1964 Hurricane Dora destroyed the Church of Our Saviour, including the stained glass window. Across the street, is the Mandarin Community Club, the former school sponsored by Stowe; the structure was given to Mandarin in 1936. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[57] Mandarin has since grown into a suburb of the expansive city of Jacksonville.

Artist Christopher Still created an oil on linen painting named The Okeehumkee on the Oklawaha River that hangs in the Florida House of Representatives. It is one of a series of images that encompass symbols of cultural and historical significance to Florida that were commissioned by the State of Florida in 1999 and completed in 2002. Palmetto Leaves is shown lying next to a large alligator and hollowed tree trunk in front of a riverboat passing through a swamp.[58]

Notes

- ↑ Kingsley and Anna Jai moved to another plantation at the mouth of the St. Johns River in 1814 where they lived for 25 years, now protected by the National Park Service as Kingsley Plantation.

- ↑ The publication of Uncle Tom's Cabin had made Stowe an international celebrity. Already active in abolitionist circles, she had been familiar with Frederick Douglass, a former slave who had educated himself and risen to prominence throughout the North, giving lectures on the evils of slavery and thinking about how a population of freed but impoverished and uneducated blacks could sustain themselves (Thulesius, p. 61–65). At some point following Uncle Tom's Cabin but before the Civil War, Stowe invited Douglass to her house and asked him this question personally. Education, according to Douglass, was the primary answer. Stowe was leaving soon on a speaking tour of England and she expected to be given a large sum of money from British sympathizers to be employed in charity work to assist runaway slaves. Douglass intended to start an industrial school for ex-slaves and anticipated she would give him about $20,000. Whether through some miscommunication, Stowe's mishandling of funds, or Douglass's own fault, Stowe eventually gave him only $500; Douglass was confused and disappointed (Thulesius, p. 65).

- ↑ Alcohol would haunt Fred Stowe for the rest of his life. He sailed to the Mediterranean to remove himself from temptation, but could not shake his addiction. In 1870, he was living with his parents in Mandarin when he resolved not to embarrass them anymore. He caught a ship to Chile, but continued to San Francisco, then a rough port. Some friends took him to a hotel, where he settled in and left to run an errand. He was never heard from again. Stowe tried in vain to have him located, and in her old age, she spoke of him constantly. (Wilson, p. 559–560.)(Stowe, Charles, p. 278–279.)

Citations

- 1 2 3 Gotta, John (September 2000). "The Anglican Aspect of Harriet Beecher Stowe", The New England Quarterly, 73 (3) p. 412–433.

- ↑ Wilson, p. 493.

- ↑ Thulesius, p. 21.

- ↑ Wilson, p. 498.

- ↑ Thulesius, p. 32.

- ↑ May, Philip S. (January 1945). "Zephaniah Kingsley, Nonconformist", The Florida Historical Quarterly 23 (3), p. 145–159.

- ↑ Wilson, p. 515.

- ↑ Stowe, Charles, p. 220–221.

- ↑ Whitfield, Stephen (April 1993). "Florida's Fudged Identity", The Florida Historical Quarterly, 71 (4), p. 413–435.

- ↑ Stover, John F. (February 2000). "Flagler, Henry Morrison", American National Biography Online. Retrieved on June 30, 2009.

- 1 2 Wakefield, Laura (Spring 2003). "'Set a Light in a Dark Place': Teachers of Freedmen in Florida, 1864-1874", The Florida Historical Quarterly, 81 (4), pp. 401–417.

- ↑ Laura Wallis Wakefield, "'Set a Light in a Dark Place': Teachers of Freedmen in Florida, 1863-1874", Fall 2004, MA Thesis, pp. 9, 12-14, University of Central Florida, accessed 17 Nov 2010

- ↑ Wilson, p. 520.

- ↑ Thulesius, p. 36.

- ↑ Thulesius, p. 117.

- ↑ Thulesius, p. 39–41.

- ↑ Wilson, p. 526–527.

- ↑ Wilson, p. 521.

- ↑ Stowe, Charles, p. 221–222.

- ↑ Thulesius, p. 69–73.

- ↑ Thulesius, p. 90.

- 1 2 3 Thulesius, p. 91.

- 1 2 3 Robbins, p. 87–89.

- ↑ Robbins, p. 83.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Eacker, Susan A. (August 1998). "Gender in Paradise: Harriet Beecher Stowe and Postbellum Prose on Florida", The Journal of Southern History, 64 (3) p. 495–512.

- 1 2 Wilson, p. 576.

- ↑ Stowe, p. 1–11.

- ↑ Stowe, p. 18.

- ↑ Thulesius, p. 78–80.

- ↑ Thulesius, p. 81.

- ↑ Stowe, p. 22.

- ↑ Stowe, p. 97–115.

- ↑ Stowe, p. 87–96.

- ↑ Stowe, p. 40–68.

- ↑ Stowe, p. 149–152.

- ↑ Stowe, p. 29–30.

- ↑ Stowe, p. 26–39.

- ↑ Stowe, p. 116–136.

- ↑ Thulesius, p. 104–115.

- ↑ Stowe, p. 260.

- ↑ Stowe, p. 298

- ↑ Stowe, p. 314–317.

- ↑ Stowe, p. 249–250.

- ↑ Stowe, p. 267–278.

- ↑ Stowe, pp. 279–321.

- ↑ Thulesius, p. 94–95.

- ↑ Wilson, p. 584.

- 1 2 Thulesius, p. 95.

- ↑ Wilson, p. 484.

- ↑ Thulesius, p. 132.

- 1 2 3 Hooker, Kenneth W. (January 1940). "A Stowe Memorial", The Florida Historical Quarterly, 18 (3) p. 198–203.

- ↑ Stowe, Charles, p. 300–301.

- ↑ Wilson, p. 621.

- ↑ "Stowe Memorial Planned; In Florida Hamlet Where the Author of "Uncle Tom's Cabin" Lived", The New York Times (April 4, 1914), p. 15.

- ↑ Thulesius, p. 141–142.

- ↑ Thulesius, p. 164.

- ↑ History, Mandarin Community Club website. Retrieved on October 4, 2009.

- ↑ "The Okeehumkee on the Oklawaha River", State of Florida website. Retrieved on October 7, 2009.

Bibliography

- Robbins, Sarah (2007). The Cambridge Introduction to Harriet Beecher Stowe, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-67153-1

- Stowe, Charles E. (1911). Harriet Beecher Stowe: The Story of Her Life, Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Stowe, Harriet B. (1873). Palmetto Leaves, J. R. Osgood and Company. (Hosted by the Florida Heritage Collection)

- Thulesius, Olav (2001). Harriet Beecher Stowe in Florida: 1867 to 1884, McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0932-0

- Wilson, Forrest (1941). Crusader in Crinoline: The Life of Harriet Beecher Stowe, J. B. Lippincott Company.

Further reading

- John T. Foster Jr. and Sarah Whitmer Foster, Beechers, Stowes, and Yankee Strangers: The Transformation of Florida, Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1999 ISBN 978-0-8130-1646-7.

External links

- Mandarin Community Club

- The Okeehumkee on the Oklawaha - painting in its entirety with guide to symbols

Palmetto_Leaves public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Palmetto_Leaves public domain audiobook at LibriVox