Paramara Kingdom of Malwa | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9th or 10th century CE–1305 CE | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Sanskrit | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Shaivism[3] | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Maharajadhiraj (Emperor) | |||||||||||||||

• 948–972 CE | Siyaka (first) | ||||||||||||||

• Late 13th century – 24 November 1305 | Mahalakadeva (last) | ||||||||||||||

| Pradhan (prime minister) | |||||||||||||||

• 948–?? CE | Vishnu (first) | ||||||||||||||

• 1275–1305 CE | Goga Deva (last) | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Classical India | ||||||||||||||

• Established | 9th or 10th century CE | ||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1305 CE | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||||||||||

The Paramara Dynasty (IAST: Paramāra)[note 1] was an Indian dynasty that ruled Malwa and surrounding areas in west-central India between 9th and 14th centuries. They belonged to the Parmara clan of the Rajputs.[5]

The dynasty was established in either the 9th or 10th century, and its early rulers most probably ruled as vassals of the Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta. The earliest extant Paramara inscriptions, issued by the 10th-century ruler Siyaka, have been found in Gujarat. Around 972 CE, Siyaka sacked the Rashtrakuta capital Manyakheta, and established the Paramaras as a sovereign power. By the time of his successor Munja, the Malwa region in present-day Madhya Pradesh had become the core Paramara territory, with Dhara (now Dhar) as their capital. The dynasty reached its zenith under Munja's nephew Bhoja, whose empire extended from Chittor in the north to Konkan in the south, and from the Sabarmati River in the west to Vidisha in the east.

The Paramara power rose and declined several times as a result of their struggles with the Chaulukyas of Gujarat, the Chalukyas of Kalyani, the Kalachuris of Tripuri, Chandelas of Jejakabhukti and other neighbouring kingdoms. The later Paramara rulers moved their capital to Mandapa-Durga (now Mandu) after Dhara was sacked multiple times by their enemies. Mahalakadeva, the last known Paramara king, was defeated and killed by the forces of Alauddin Khalji of Delhi in 1305 CE, although epigraphic evidence suggests that the Paramara rule continued for a few years after his death.

Malwa enjoyed a great level of political and cultural prestige under the Paramaras. The Paramaras were well known for their patronage to Sanskrit poets and scholars, and Bhoja was himself a renowned scholar. Most of the Paramara kings were Shaivites and commissioned several Shiva temples, although they also patronized Jain scholars.

Origin

Ancestry

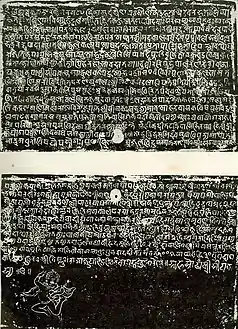

The Harsola copper plates (949 CE) issued by the Paramara king Siyaka II mentions a king called Akalavarsha, followed by the expression tasmin kule ("in that family"), and then followed by the name "Vappairaja" (identified with the Paramara king Vakpati I).[6] Based on the identification of "Akalavarsha" (which was a Rashtrakuta title) with the Rashtrakuta king Krishna III, historian as D.C. Ganguly theorized that the Paramaras were descended from the Rashtrakutas.[7] Ganguly tried to find support for his theory in Ain-i-Akbari, whose variation of the Agnikula myth (see below) states that a predecessor of the Paramaras came to Malwa from Deccan.[8] According to Ain-i-Akbari, Dhanji - a man born from a fire sacrifice - came from Deccan to establish a kingdom in Malwa; when his descendant Putraj died heirless, the nobles established Aditya Ponwar - the ancestor of the Paramaras - as the new king.[9] Ganguly also noted Siyaka's successor Munja (Vakpati II) assumed titles such as Amoghavarsha, Sri-vallabha and Prithvi-vallabha: these are distinctively Rashtrakuta titles.[10]

However, there is a gap before the words tasmin kule ("in that family") in the Harsola inscription, and therefore, Ganguly's suggestion is a pure guess in absence of any concrete evidence.[11] Moreover, even if the Ain-i-Akbari legend is historically accurate, Aditya Ponwar was not a descendant of Dhanji: he was most probably a local magnate rather than a native of Deccan.[12][13] Critics of Ganguly's theory also argue that the Rashtrakuta titles in these inscriptions refer to Paramara rulers, who had assumed these titles to portray themselves as the legitimate successors of the Rashtrakutas in the Malwa region.[14] The Rashtrakutas had similarly adopted the titles such as Prithvi-vallabha, which had been used by the preceding Chalukya rulers.[14] Historian Dasharatha Sharma points out that the Paramaras claimed the mythical Agnikula origin by the 10th century: had they really been descendants of the Rashtrakutas, they would not have forgotten their prestigious royal origin within a generation.[10]

The later Paramara kings claimed to be members of the Agnikula or Agnivansha ("fire clan"). The Agnikula myth of origin, which appears in several of their inscriptions and literary works, goes like this: The sage Vishvamitra forcibly took a wish-granting cow from another sage Vashistha on the Arbuda mountain (Mount Abu). Vashistha then conjured a hero from a sacrificial fire pit (agni-kunda), who defeated Vishvamitra's enemies and brought back the cow. Vashistha then gave the hero the title Paramara ("enemy killer").[15] The earliest known source to mention this story is the Nava-sahasanka-charita of Padmagupta Parimala, who was a court-poet of the Paramara king Sindhuraja (c. 997–1010).[16] The legend is not mentioned in earlier Paramara-era inscriptions or literary works. By this time, all the neighbouring dynasties claimed divine or heroic origin, which might have motivated the Paramaras to invent a legend of their own.[17][14]

A legend mentioned in a recension of Prithviraj Raso extended their Agnikula legend to describe other dynasties as fire-born Rajputs. The earliest extant copies of Prithviraj Raso do not contain this legend; this version might have been invented by the 16th-century poets who wanted to foster Rajput unity against the Mughal emperor Akbar.[18] Some colonial-era historians interpreted this mythical account to suggest a foreign origin for the Paramaras. According to this theory, the ancestors of the Paramaras and other Agnivanshi Rajputs came to India after the decline of the Gupta Empire around the 5th century CE. They were admitted in the Hindu caste system after performing a fire ritual.[19] However, this theory is weakened by the fact that the legend is not mentioned in the earliest of the Paramara records, and even the earliest Paramara-era account does not mention the other dynasties as Agnivanshi.[20]

Some historians, such as Dasharatha Sharma and Pratipal Bhatia, have argued that the Paramaras were originally Brahmins from the Vashistha gotra.[8] This theory is based on the fact that Halayudha, who was patronized by Munja, describes the king as "Brahma-Kshtra" in Pingala-Sutra-Vritti. According to Bhatia this expression means that Munja came from a family of Brahmins who became Kshatriyas.[21] In addition, the Patanarayana temple inscription states that the Paramaras were of Vashistha gotra, which is a gotra among Brahmins claiming descent from the sage Vashistha.[22] However, historian Arvind K. Singh points out that several other sources point to a Kshatriya ancestry of the dynasty. For example, the 1211 Piplianagar inscription states that the ancestors of the Paramaras were "crest-jewel of the Kshatriyas", and the Prabha-vakara-charita mentions that Vakpati was born in the dynasty of a Kshatriya. According to Singh, the expression "Brahma-Kshatriya" refers to a learned Kshatriya.[14]

D. C. Sircar theorized that the dynasty descended from the Malavas. However, there is no evidence of the early Paramara rulers being called Malava; the Paramaras began to be called Malavas only after they began ruling the Malwa region.[8]

A Chaulukya-Paramara coin, c. 950-1050 CE. Stylized rendition of Chavda dynasty coins: Indo-Sassanian style bust right; pellets and ornaments around / Stylised fire altar; pellets around.[23]

A Chaulukya-Paramara coin, c. 950-1050 CE. Stylized rendition of Chavda dynasty coins: Indo-Sassanian style bust right; pellets and ornaments around / Stylised fire altar; pellets around.[23] Coin of the Paramara king Naravarman, c. 1094–1133. Goddess Lakshmi seated facing / Devanagari legend.[24]

Coin of the Paramara king Naravarman, c. 1094–1133. Goddess Lakshmi seated facing / Devanagari legend.[24] Coin of the Paramara prince Jagadeva, 12th-13th centuries CE.

Coin of the Paramara prince Jagadeva, 12th-13th centuries CE.

Original homeland

Based on the Agnikula legend, some scholars such as C. V. Vaidya and V. A. Smith speculated that Mount Abu was the original home of the Paramaras. Based on the Harsola copper plates and Ain-i-Akbari, D. C. Ganguly believed they came from the Deccan region.[25]

The earliest of the Paramara inscriptions (that of Siyaka II) have all been discovered in Gujarat, and concern land grants in that region. Based on this, D. B. Diskalkar and H. V. Trivedi theorized that the Paramaras were associated with Gujarat during their early days.[26] Another possibility is that the early Paramara rulers temporarily left their capital city of Dhara in Malwa for Gujarat because of a Gurjara-Pratihara invasion. This theory is based on the combined analysis of two sources: the Nava-sahasanka-charita, which states that the Paramara king Vairisimha cleared the Dhara city in Malwa of enemies; and the 945-946 CE Pratapgah inscription of the Gurjara-Prathiara king Mahendrapala, which states that he recaptured Malwa.[27]

Early rulers

Whether or not the Paramaras were descended from the Rashtrakutas, they were most probably subordinates of the Rashtrakutas in the 9th century.[14] Historical evidence suggests that between 808 and 812 CE, the Rashtrakutas expelled the Gurjara-Pratiharas from the Malwa region. The Rashtrakuta king Govinda III placed Malwa under the protection of Karka-raja, the Rashtrakuta chief of Lata (a region bordering Malwa, in present-day Gujarat).[28] The 871 Sanjan copper-plate inscription of Govinda's son Amoghavarsha I states that his father had appointed a vassal as the governor of Malwa. Since the Paramaras became the rulers of the Malwa region around this time, epigraphist H. V. Trivedi theorizes that this vassal was the Paramara king Upendra,[14] although there is no definitive proof of this. The start of the Paramara rule in Malwa cannot be dated with certainty, but they certainly did not rule the Malwa before the 9th century CE.[28]

Siyaka is the earliest known Paramara king attested by his own inscriptions. His Harsola copper plate inscription (949 CE) is the earliest available Paramara inscription: it suggests that he was a vassal of the Rashtrakutas.[6] The list of his predecessors varies between accounts:[29][6]

| Harsola copper plates (949 CE) | Nava-Sahasanka-Charita (early 11th century) | Udaipur Prashasti inscription (11th century) | Nagpur Prashasti inscription (1104 CE) | Other land grants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paramara | Paramara | Paramara | Paramara | |

| Upendra | Upendra | Krishna | ||

| "Other kings" | Vairisimha (I) | |||

| Siyaka (I) | ||||

| Vappairaja | Vakpati (I) | Vakpati (I) | ||

| Vairisimha | Vairisimha | Vairisimha (II) | Vairisimha | Vairisimha |

| Siyaka | Siyaka alias Harsha | Harsha | Siyaka | Siyaka |

Paramara is the dynasty's mythical progenitor, according to the Agnikula legend. Whether the other early kings mentioned in the Udaipur Prashasti are historical or fictional is a topic of debate among historians.[30]

According to C. V. Vaidya and K. A. Nilakantha Sastri, the Paramara dynasty was founded only in the 10th century CE. Vaidya believes that the kings such as Vairisimha I and Siyaka I are imaginary, duplicated from the names of later historical kings in order to push back the dynasty's age.[30] The 1274 CE Mandhata copper-plate inscription of Jayavarman II similarly names eight successors of Paramara as Kamandaludhara, Dhumraja, Devasimhapala, Kanakasimha, Shriharsha, Jagaddeva, Sthirakaya and Voshari: these do not appear to be historical figures.[31] HV Trivedi states that there is a possibility that Vairisimha I and Siyaka I of the Udaipur Prashasti are same as Vairisimha II and Siyaka II; the names might have been repeated by mistake. Alternatively, he theorizes that these names have been omitted in other inscriptions because these rulers were not independent sovereigns.[6]

Several other historians believe that the early Paramara rulers mentioned in the Udaipur Prashasti are not fictional, and the Paramaras started ruling Malwa in the 9th century (as Rashtrakuta vassals). K. N. Seth argues that even some of the later Paramara inscriptions mention only 3-4 predecessors of the king who issued the inscription. Therefore, the absence of certain names from the genealogy provided in the early inscriptions does not mean that these were imaginary rulers. According to him, the mention of Upendra in Nava-Sahasanka-Charitra (composed by the court poet of the later king Sindhuraja) proves that Upendra is not a fictional king.[32] Historians such as Georg Bühler and James Burgess identify Upendra and Krishnaraja as one person, because these are synonyms (Upendra being another name of Krishna). However, an inscription of Siyaka's successor Munja names the preceding kings as Krishnaraja, Vairisimha, and Siyaka. Based on this, Seth however identifies Krishnaraja with Vappairaja or Vakpati I mentioned in the Harsola plates (Vappairaja appears to be the Prakrit form of Vakpati-raja). In his support, Seth points out that Vairisimha has been called Krishna-padanudhyata in the inscription of Munja i.e. Vakpati II. He theorizes that Vakpati II used the name "Krishnaraja" instead of Vakpati I to identify his ancestor, in order to avoid confusion with his own name.[32]

The imperial Paramaras

The first independent sovereign of the Paramara dynasty was Siyaka (sometimes called Siyaka II to distinguish him from the earlier Siyaka mentioned in the Udaipur Prashasti). The Harsola copper plates (949 CE) suggest that Siyaka was a feudatory of the Rashtrakuta ruler Krishna III in his early days. However, the same inscription also mentions the high-sounding Maharajadhirajapati as one of Siyaka's titles. Based on this, K. N. Seth believes that Siyaka's acceptance of the Rashtrakuta lordship was nominal.[33]

As a Rashtrakuta feudatory, Siyaka participated in their campaigns against the Pratiharas. He also defeated some Huna chiefs ruling to the north of Malwa.[34] He might have suffered setbacks against the Chandela king Yashovarman.[35] After the death of Krishna III, Siyaka defeated his successor Khottiga in a battle fought on the banks of the Narmada River. He then pursued Khottiga's retreating army to the Rashtrakuta capital Manyakheta, and sacked that city in 972 CE. His victory ultimately led to the decline of the Rashtrakutas, and the establishment of the Paramaras as an independent sovereign power in Malwa.[36]

Siyaka's successor Munja achieved military successes against the Chahamanas of Shakambari, the Chahamanas of Naddula, the Guhilas of Mewar, the Hunas, the Kalachuris of Tripuri, and the ruler of Gurjara region (possibly a Gujarat Chaulukya or Pratihara ruler).[37] He also achieved some early successes against the Western Chalukya king Tailapa II, but was ultimately defeated and killed by Tailapa some time between 994 CE and 998 CE.[38][39]

As a result of this defeat, the Paramaras lost their southern territories (possibly the ones beyond the Narmada river) to the Chalukyas.[40] Munja was reputed as a patron of scholars, and his rule attracted scholars from different parts of India to Malwa.[41] He was also a poet himself, although only a few stanzas composed by him now survive.[42]

Munja's brother Sindhuraja (ruled c. 990s CE) defeated the Western Chalukya king Satyashraya, and recovered the territories lost to Tailapa II.[43] He also achieved military successes against a Huna chief, the Somavanshi of south Kosala, the Shilaharas of Konkana, and the ruler of Lata (southern Gujarat).[43] His court poet Padmagupta wrote his biography Nava-Sahasanka-Charita, which credits him with several other victories, although these appear to be poetic exaggerations.[44]

Sindhuraja's son Bhoja is the most celebrated ruler of the Paramara dynasty. He made several attempts to expand the Paramara kingdom varying results. Around 1018 CE, he defeated the Chalukyas of Lata in present-day Gujarat.[45] Between 1018 CE and 1020 CE, he gained control of the northern Konkan, whose Shilahara rulers probably served as his feudatories for a brief period.[46][47] Bhoja also formed an alliance against the Kalyani Chalukya king Jayasimha II, with Rajendra Chola and Gangeya-deva Kalachuri. The extent of Bhoja's success in this campaign is not certain, as both Chalukya and Paramara panegyrics claimed victory.[48] During the last years of Bhoja's reign, sometime after 1042 CE, Jayasimha's son and successor Someshvara I invaded Malwa, and sacked his capital Dhara.[43] Bhoja re-established his control over Malwa soon after the departure of the Chalukya army, but the defeat pushed back the southern boundary of his kingdom from Godavari to Narmada.[49][50]

.jpg.webp)

Bhoja's attempt to expand his kingdom eastwards was foiled by the Chandela king Vidyadhara.[51] However, Bhoja was able to extend his influence among the Chandela feudatories, the Kachchhapaghatas of Dubkund.[52] Bhoja also launched a campaign against the Kachchhapaghatas of Gwalior, possibly with the ultimate goal of capturing Kannauj, but his attacks were repulsed by their ruler Kirtiraja.[53] Bhoja also defeated the Chahamanas of Shakambhari, killing their ruler Viryarama. However, he was forced to retreat by the Chahamanas of Naddula.[54] According to medieval Muslim historians, after sacking Somnath, Mahmud of Ghazni changed his route to avoid confrontation with a Hindu king named Param Dev. Modern historians identify Param Dev as Bhoja: the name may be a corruption of Paramara-Deva or of Bhoja's title Parameshvara-Paramabhattaraka.[55][56] Bhoja may have also contributed troops to support the Kabul Shahi ruler Anandapala's fight against the Ghaznavids.[57] He may have also been a part of the Hindu alliance that expelled Mahmud's governors from Hansi, Thanesar and other areas around 1043 CE.[58][43] During the last year of Bhoja's reign, or shortly after his death, the Chaulukya king Bhima I and the Kalachuri king Karna attacked his kingdom. According to the 14th-century author Merutunga, Bhoja died of a disease at the same time the allied army attacked his kingdom.[59][60]

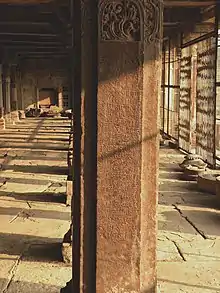

At its zenith, Bhoja's empire extended from Chittor in the north to upper Konkan in the south, and from the Sabarmati River in the west to Vidisha in the east.[61] He was recognized as a capable military leader, but his territorial conquests were short-lived. His major claim to fame was his reputation as a scholar-king, who patronized arts, literature and sciences. Noted poets and writers of his time sought his sponsorship.[62] Bhoja was himself a polymath, whose writings cover a wide variety of topics include grammar, poetry, architecture, yoga, and chemistry. Bhoja established the Bhoj Shala which was a centre for Sanskrit studies and a temple of Sarasvati in present-day Dhar. He is said to have founded the city of Bhojpur, a belief supported by historical evidence. Besides the Bhojeshwar Temple there, the construction of three now-breached dams in that area is attributed to him.[63] Because of his patronage to literary figures, several legends written after his death featured him as a righteous scholar-king.[64] In terms of the number of legends centered around him, Bhoja is comparable to the fabled Vikramaditya.[65]

Decline

Bhoja's successor Jayasimha I, who was probably his son,[66] faced the joint Kalachuri-Chaulukya invasion immediately after Bhoja's death.[67] Bilhana's writings suggest that he sought help from the Chalukyas of Kalyani.[68] Jayasimha's successor and Bhoja's brother Udayaditya was defeated by Chamundaraja, his vassal at Vagada. He repulsed an invasion by the Chaulukya ruler Karna, with help from his allies. Udayaditya's eldest son Lakshmadeva has been credited with extensive military conquests in the Nagpur Prashasti inscription of 1104-05 CE. However, these appear to be poetic exaggerations. At best, he might have defeated the Kalachuris of Tripuri.[69] Udayaditya's younger son Naravarman faced several defeats, losing to the Chandelas of Jejakabhukti and the Chaulukya king Jayasimha Siddharaja. By the end of his reign, one Vijayapala had carved out an independent kingdom to the north-east of Ujjain.[70]

Yashovarman lost control of the Paramara capital Dhara to Jayasimha Siddharaja. His successor Jayavarman I regained control of Dhara, but soon lost it to an usurper named Ballala.[71] The Chaulukya king Kumarapala defeated Ballala around 1150 CE, supported by his feudatories the Naddula Chahamana ruler Alhana and the Abu Paramara chief Yashodhavala. Malwa then became a province of the Chaulukyas. A minor branch of the Paramaras, who styled themselves as Mahakumaras, ruled the area around Bhopal during this time.[72] Nearly two decades later, Jayavarman's son Vindhyavarman defeated the Chaulukya king Mularaja II, and re-established the Paramara sovereignty in Malwa.[73] During his reign, Malwa faced repeated invasions from the Hoysalas and the Yadavas of Devagiri.[74] He was also defeated by the Chaulukya general Kumara.[75] Despite these setbacks, he was able to restore the Paramara power in Malwa before his death.[76]

Vindhyavarman's son Subhatavarman invaded Gujarat, and plundered the Chaulukya territories. But he was ultimately forced to retreat by the Chaulukya feudatory Lavana-Prasada.[77] His son Arjunavarman I also invaded Gujarat, and defeated Jayanta-simha (or Jaya-simha), who had usurped the Chaulukya throne for a brief period.[78] He was defeated by Yadava general Kholeshvara in Lata.[79]

Arjunavarman was succeeded by Devapala, who was the son of Harishchandra, a Mahakumara (chief of a Paramara branch).[79] He continued to face struggles against the Chaulukyas and the Yadavas. The Sultan of Delhi Iltutmish captured Bhilsa during 1233-34 CE, but Devapala defeated the Sultanate's governor and regained control of Bhilsa.[81][82] According to the Hammira Mahakavya, he was killed by Vagabhata of Ranthambhor, who suspected him of plotting his murder in connivance with the Delhi Sultan.[83]

During the reign of Devapala's son Jaitugideva, the power of the Paramaras greatly declined because of invasions from the Yadava king Krishna, the Delhi Sultan Balban, and the Vaghela prince Visala-deva.[84] Devapala's younger son Jayavarman II also faced attacks from these three powers. Either Jaitugi or Jayavarman II moved the Paramara capital from Dhara to the hilly Mandapa-Durga (present-day Mandu), which offered a better defensive position.[85]

Arjunavarman II, the successor of Jayavarman II, proved to be a weak ruler. He faced rebellion from his minister.[86] In the 1270s, the Yadava ruler Ramachandra invaded Malwa,[87] and in the 1280s, the Ranthambhor Chahamana ruler Hammira also raided Malwa.[88] Arjuna's successor Bhoja II also faced an invasion from Hammira. Bhoja II was either a titular ruler controlled by his minister, or his minister had usurped a part of the Paramara kingdom.[89]

Mahalakadeva, the last known Paramara king, was defeated and killed by the army of Ayn al-Mulk Multani in 1305 CE.[90][91]

List of rulers

According to historical 'Kailash Chand Jain', "Knowledge of the early Paramara rulers from Upendra to Vairisimha is scanty; there are no records, and they are known only from later sources."[92] The Paramara rulers mentioned in the various inscriptions and literary sources include:

| Serial No. | Ruler | Reign (CE) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Paramara | mythical |

| 2 | Upendra Krishnraja | early 9th century |

| 3 | Vairisimha (I) | early 9th century |

| 4 | Siyaka (I) | mid of 9th century |

| 5 | Vakpatiraj (I) | late 9th to early 10th century |

| 6 | Vairisimha (II) | mid of 10th century |

| 7 | Siyaka (II) | 940–972 |

| 8 | Vakpatiraj (II) alias Munja | 972–990 |

| 9 | Sindhuraja | 990–1010 |

| 10 | Bhoja | 1010–1055 |

| 11 | Jayasimha I | 1055–1070 |

| 12 | Udayaditya | 1070–1086 |

| 13 | Lakshmadeva | 1086–1094 |

| 14 | Naravarman | 1094–1133 |

| 15 | Yashovarman | 1133–1142 |

| 16 | Jayavarman I | 1142–1143 |

| 17 | Interregnum from (1143 to 1175 CE) under an usurper named 'Ballala' and later the Solanki king Kumarapala | 1143–1175 |

| 18 | Vindhyavarman | 1175–1194 |

| 19 | Subhatavarman | 1194–1209 |

| 20 | Arjunavarman I | 1210–1215 |

| 21 | Devapala | 1215/1218–1239 |

| 22 | Jaitugideva | 1239–1255 |

| 23 | Jayavarman II | 1255–1274 |

| 24 | Arjunavarman II | 1274–1285 |

| 25 | Bhoja II | 1285–1301 |

| 26 | Mahalakadeva | 1301–1305 |

After death of Mahalakadeva in 1305 CE, Paramara dynasty rule was ended in Malwa region, but not in other Parmar states.

An inscription from Udaipur indicates that the Paramara dynasty survived until 1310, at least in the north-eastern part of Malwa. A later inscription shows that the area had been captured by the Delhi Sultanate by 1338.[93]

Branches and claimed descendants

Besides the Paramara sovereigns of Malwa, several branches of the dynasties ruled as feudatories at various places. These include:

- Paramaras of Chandravati

- Ruled the Arbuda-mandala (Mount Abu area)[94]

- Became feudatories of the Chaulukyas of Gujarat by the 12th century[95]

- Paramaras of Bhinmal-Kiradu

- Paramaras of Jalor

- Another branch of the Paramaras of Chandravati[94]

- Supplanted by the Chahamanas of Jalor[97]

- Paramaras of Vagada

The rulers of several princely states claimed connection with the Paramaras. These include:

- Baghal State: It is said to have been founded by Ajab Dev Parmar, who came to present-day Himachal Pradesh from Ujjain in the 14th century.[99]

- Danta State: Its rulers claimed membership of the Parmar clan and descent from the legendary king Vikramaditya of Ujjain[100]

- Dewas State (Senior and Junior): The Maratha Puar rulers of these states claimed descent from the Paramara dynasty.[101]

- Dhar State: Its founder Anand Rao Puar, who claimed Paramara descent, received a fief from Peshwa Baji Rao I in the 18th century.[102]

- Muli State: Its rulers claimed Paramara descent, and are said to have started out as feudatories of the Vaghelas.[103]

- Narsinghgarh State

- Jagdishpur and Dumraon: The Rajputs of Bhojpur district in present-day Bihar, who styled themselves as Ujjainiya Panwar Rajputs, started claiming descent from the royal family of Ujjain in the 17th century.[104] The Rajas of Jagdishpur and Dumraon in Bihar claimed descent from the Ujjainia branch of Paramaras.[105]

- The Gandhawaria Rajputs of Mithila and the Ujjainiyas of Bhojpur also claim descent from the Paramara dynasty.[106][107]

See also

Notes

References

- Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 147, map XIV.3 (a). ISBN 0226742210.

- ↑ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 147, map XIV.3 (a). ISBN 0226742210.

- ↑ R.K. Gupta, S.R. Bakshi (2008). Rajasthan Through the Ages, Studies in Indian history. Vol. 1. Rajasthan: Swarup & Sons. p. 43. ISBN 9788176258418.

Parmara rulers were devout shaivas.

- ↑ Benjamin Walker 1995, p. 186.

- ↑

- Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya (2006). Studying Early India: Archaeology, Texts and Historical Issues. Anthem. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-84331-132-4.

The period between the seventh and the twelfth century witnessed gradual rise of a number of new royal-lineages in Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, which came to constitute a social-political category known as 'Rajput'. Some of the major lineages were the Pratiharas of Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and adjacent areas, the Guhilas and Chahamanas of Rajasthan, the Caulukyas or Solankis of Gujarat and Rajasthan and the Paramaras of Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan.

- Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya (2006). Studying Early India: Archaeology, Texts and Historical Issues. Anthem. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-84331-132-4.

- 1 2 3 4 H. V. Trivedi 1991, p. 4.

- ↑ R.K. Gupta, S.R. Bakshi (2008). Rajasthan Through the Ages, Studies in Indian history. Rajasthan: Swarup & Sons. p. 24. ISBN 9788176258418.

- 1 2 3 Kailash Chand Jain 1972, p. 327.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, p. 4.

- 1 2 Ganga Prasad Yadava 1982, p. 36.

- ↑ H. V. Trivedi (Introduction) 1991, p. 4.

- ↑ Pratipal Bhatia 1970, p. 18.

- ↑ R. B. Singh 1975, p. 225.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Arvind K. Singh 2012, p. 14.

- ↑ Ganga Prasad Yadava 1982, p. 32.

- ↑ Alf Hiltebeitel 2009, p. 444.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, pp. 10–13.

- ↑ R. B. Singh 1964, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Ganga Prasad Yadava 1982, p. 35.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, p. 16.

- ↑ Ganga Prasad Yadava 1982, p. 37.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, p. 29.

- ↑ "CNG: EAuction 329. INDIA, Post-Gupta (Chaulukya-Paramara). Circa AD 950-1050. AR Drachm (16mm, 4.41 g, 6h)". Archived from the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ↑ "CNG Coins". Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, p. 30.

- ↑ H. V. Trivedi 1991, p. 9.

- ↑ Arvind K. Singh 2012, p. 16.

- 1 2 Krishna Narain Seth 1978, pp. 44–47.

- ↑ Mahesh Singh 1984, pp. 3–4.

- 1 2 Krishna Narain Seth 1978, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ H. V. Trivedi 1991, p. 212.

- 1 2 Krishna Narain Seth 1978, pp. 48–51.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, p. 79.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1972, p. 334.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, pp. 81–84.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1972, p. 336-338.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, pp. 102–104.

- ↑ M. Srinivasachariar 1974, p. 502.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1972, pp. 339–340.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1972, pp. 340–341.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, p. 105.

- 1 2 3 4 Sailendra Nath Sen 1999, p. 320.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1972, p. 341.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, p. 137.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, pp. 140–141.

- ↑ Mahesh Singh 1984, p. 46.

- ↑ Saikat K. Bose 2015, p. 27.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, p. 154.

- ↑ Mahesh Singh 1984, p. 56.

- ↑ Mahesh Singh 1984, p. 69.

- ↑ Mahesh Singh 1984, pp. 172–173.

- ↑ Mahesh Singh 1984, pp. 173.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, p. 177.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, pp. 163–165.

- ↑ Mahesh Singh 1984, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, p. 158.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, p. 166.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, p. 182.

- ↑ Mahesh Singh 1984, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Kirit Mankodi 1987, p. 62.

- ↑ Sheldon Pollock 2003, p. 179.

- ↑ Kirit Mankodi 1987, p. 71.

- ↑ Sheldon Pollock 2003, pp. 179–180.

- ↑ Anthony Kennedy Warder 1992, pp. 176.

- ↑ Anthony Kennedy Warder 1992, pp. 177.

- ↑ Krishna Narain Seth 1978, pp. 182–184.

- ↑ Prabhakar Narayan Kawthekar 1995, p. 72.

- ↑ H. V. Trivedi 1991, p. 110.

- ↑ Pratipal Bhatia 1970, p. 115-122.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1972, pp. 362–363.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1972, pp. 363–364.

- ↑ R. C. Majumdar 1977, p. 328.

- ↑ H. V. Trivedi 1991, p. 162.

- ↑ Pratipal Bhatia 1970, p. 137.

- ↑ Sailendra Nath Sen 1999, p. 322.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1972, p. 370.

- ↑ Asoke Kumar Majumdar 1956, p. 148.

- 1 2 Kailash Chand Jain 1972, p. 371.

- ↑ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 21, 147. ISBN 0226742210.

- ↑ H. V. Trivedi 1991, pp. 188.

- ↑ D. C. Sircar 1966, pp. 187–188.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1972, p. 372.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1972, p. 373.

- ↑ H. V. Trivedi 1991, p. 203.

- ↑ Asoke Kumar Majumdar 1977, p. 445.

- ↑ Pratipal Bhatia 1970, p. 158.

- ↑ Dasharatha Sharma 1975, p. 124.

- ↑ Pratipal Bhatia 1970, p. 160.

- ↑ Sailendra Nath Sen 1999, p. 25.

- ↑ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 395.

- ↑ Jain, Kailash Chand (1972). Malwa Through the Ages, from the Earliest Times to 1305 A.D. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 329. ISBN 978-81-208-0824-9.

- ↑ Peter Jackson 2003, p. 199.

- 1 2 3 4 Arvind K. Singh 2012, p. 13.

- ↑ H. V. Trivedi 1991, p. 244.

- ↑ H. V. Trivedi 1991, p. 321.

- ↑ H. V. Trivedi 1991, p. 333.

- ↑ H. V. Trivedi 1991, p. 280.

- ↑ Poonam Minhas 1998, p. 49.

- ↑ Tony McClenaghan 1996, p. 115.

- ↑ John Middleton 2015, p. 236.

- ↑ Tony McClenaghan 1996, p. 122.

- ↑ Virbhadra Singhji 1994, p. 44.

- ↑ Dirk H. A. Kolff (8 August 2002). Naukar, Rajput, and Sepoy: The Ethnohistory of the Military Labour Market of Hindustan, 1450-1850. Cambridge University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-521-52305-9. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ↑ The Journal of the Bihar Purāvid Parishad, Volumes=7-8. Bihar Puravid Parishad. 1983. p. 411. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ "The Journal of the Bihar Purāvid Parishad". Bihar Puravid Parishad. 1983. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ Ahmad, Imtiaz (2008). "State Formation and Consolidation under the Ujjainiya Rajputs in Medieval Bihar: Testimony of Oral Traditions as Recorded in the Tawarikh-i-Ujjainiya". In Singh, Surinder; Gaur, I. D. (eds.). Popular Literature And Pre-Modern Societies In South Asia. Pearson Education India. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-81-317-1358-7. Archived from the original on 25 December 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

Bibliography

| History of South Asia |

|---|

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png.webp) |

- Alf Hiltebeitel (2009). Rethinking India's Oral and Classical Epics. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226340555. Archived from the original on 23 March 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- Arvind K. Singh (2012). "Interpreting the History of the Paramāras". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 22 (1): 13–28. JSTOR 41490371.

- Asoke Kumar Majumdar (1956). Chaulukyas of Gujarat. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. OCLC 4413150. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- Asoke Kumar Majumdar (1977). Concise History of Ancient India: Political history. Munshiram Manoharlal. OCLC 5311157. Archived from the original on 23 March 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- Anthony Kennedy Warder (1992). "XLVI: The Vikramaditya Legend". Indian Kāvya Literature: The art of storytelling. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0615-3.

- Cynthia Talbot (2015). The Last Hindu Emperor: Prithviraj Cauhan and the Indian Past, 1200–2000. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107118560.

- D. C. Sircar (1966). "Bhilsa inscription of the time of Jayasimha, Vikrama 1320". Epigraphia Indica. Vol. 35. Archaeological Survey of India.

- Dasharatha Sharma (1975). Early Chauhān Dynasties: A Study of Chauhān Political History, Chauhān Political Institutions, and Life in the Chauhān Dominions, from 800 to 1316 A.D. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-0-8426-0618-9. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- David P. Henige (2004). Princely States of India: A Guide to Chronology and Rulers. Orchid. ISBN 978-974-524-049-0. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- Ganga Prasad Yadava (1982). Dhanapāla and His Times: A Socio-cultural Study Based Upon His Works. Concept. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- Georg Bühler (1892). "The Udepur Prasasti of the Kings of Malva". Epigraphia Indica. Vol. 1. Archaeological Survey of India.

- Harihar Vitthal Trivedi (1991). Introduction to Inscriptions of the Paramaras, Chandellas, Kachchhapaghatas, etc. (Part 1). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Volume VII: Inscriptions of the Paramāras, Chandēllas, Kachchapaghātas, and two minor dynasties. Archaeological Survey of India. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1451761. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- Harihar Vitthal Trivedi (1991). Inscriptions of the Paramāras (Part 2). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Volume VII: Inscriptions of the Paramāras, Chandēllas, Kachchapaghātas, and two minor dynasties. Archaeological Survey of India. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1451755. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- John Middleton (2015). World Monarchies and Dynasties. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-45158-7.

- Kailash Chand Jain (1972). Malwa Through the Ages, from the Earliest Times to 1305 A.D. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0824-9. Archived from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- Kirit Mankodi (1987). "Scholar-Emperor and a Funerary Temple: Eleventh Century Bhojpur". Marg. National Centre for the Performing Arts. 39 (2): 61–72. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- Krishna Narain Seth (1978). The Growth of the Paramara Power in Malwa. Progress. OCLC 8931757. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- M. Srinivasachariar (1974). History of Classical Sanskrit Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120802841. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- Mahesh Singh (1984). Bhoja Paramāra and His Times. Bharatiya Vidya Prakashan. OCLC 11786897. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- Poonam Minhas (1998). Traditional Trade & Trading Centres in Himachal Pradesh: With Trade-routes and Trading Communities. Indus Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7387-080-4.

- Prabhakar Narayan Kawthekar (1995). Bilhana. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 9788172017798. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- Peter Jackson (2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54329-3. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- Pratipal Bhatia (1970). The Paramāras, c. 800-1305 A.D. Munshiram Manoharlal. OCLC 199886. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- R. B. Singh (1964). History of the Chāhamānas. N. Kishore. OCLC 11038728. Archived from the original on 23 March 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- R. C. Majumdar (1977). Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120804364. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- Saikat K. Bose (2015). Boot, Hooves and Wheels: And the Social Dynamics behind South Asian Warfare. Vij. ISBN 978-9-38446-454-7.

- Sailendra Nath Sen (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. ISBN 9788122411980. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- Sheldon Pollock (2003). The Language of the Gods in the World of Men: Sanskrit, Culture, and Power in Premodern India. University of California Press. ISBN 0-5202-4500-8. Archived from the original on 23 March 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- Tony McClenaghan (1996). Indian Princely Medals. Lancer. ISBN 978-1-897829-19-6.

- Virbhadra Singhji (1994). The Rajputs of Saurashtra. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7154-546-9.

- R. B. Singh (1975). Origin of Rajputs. Sahitya Sansar Prakashan. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- Virendra N. Mishra (2007). Rajasthan: Prehistoric and Early Historic Foundations. Aryan books International. ISBN 9788173053214.

- Benjamin Walker (1995). Hindu World vol.2. Indus. ISBN 81-7223-179-2.