| Youth rights |

|---|

|

Physical or corporal punishment by a parent or other legal guardian is any act causing deliberate physical pain or discomfort to a minor child in response to some undesired behavior. It typically takes the form of spanking or slapping the child with an open hand or striking with an implement such as a belt, slipper, cane, hairbrush or paddle, whip, hanger, and can also include shaking, pinching, forced ingestion of substances, or forcing children to stay in uncomfortable positions.

Social acceptance of corporal punishment is high in countries where it remains lawful, particularly among more traditional groups. In many cultures, parents have historically been regarded as having the right, if not the duty, to physically punish misbehaving children in order to teach appropriate behavior. Researchers, on the other hand, point out that corporal punishment typically has the opposite effect, leading to more aggressive behavior in children and less long-term obedience.[1] Other adverse effects, such as depression, anxiety, anti-social behavior and increased risk of physical abuse, have also been linked to the use of corporal punishment by parents.[2] Evidence shows that spanking and other physical punishments, while nominally for the purpose of child discipline, are inconsistently applied, often being used when parents are angry or under stress.[3] Severe forms of corporal punishment, including kicking, biting, scalding and burning, can also constitute child abuse.

International human-rights and treaty bodies such as the Committee on the Rights of the Child, the Council of Europe and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights have advocated an end to all forms of corporal punishment, arguing that it violates children's dignity and right to bodily integrity. Many existing laws against battery, assault, and/or child abuse make exceptions for "reasonable" physical punishment by parents, a defence rooted in common law and specifically English law. During the late 20th and into the 21st century, some countries began removing legal defences for adult guardians' use of corporal punishment, followed by outright bans on the practice. Most of these bans are part of civil law and therefore do not impose criminal penalties unless a charge of assault and/or battery is justified; however, the local child protective services can and will often intervene.

Ever since Sweden outlawed all corporal punishment of children in 1979, an increasing number of countries have enacted similar bans, particularly following international adoption of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. As of 2021, this comprises 22 of the 27 member states of the European Union as well as 26 of the 38 countries belonging to the OECD. However, domestic corporal punishment of children remains legal in most of the world.

Forms of punishment

The Committee on the Rights of the Child defines corporal punishment as "any punishment in which physical force is used and intended to cause some degree of pain or discomfort, however light".[4] Paulo Sergio Pinheiro, reporting on a worldwide study on violence against children for the Secretary General of the United Nations, writes:

Corporal punishment involves hitting ('smacking', 'slapping', 'spanking') children, with the hand or with an implement – whip, stick, belt, shoe, wooden spoon, etc. But it can also involve, for example, kicking, shaking or throwing children, scratching, pinching, biting, pulling hair or boxing ears, forcing children to stay in uncomfortable positions, burning, scalding or forced ingestion (for example, washing children's mouths out with soap or forcing them to swallow hot spices).[4]

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, "Corporal punishment involves the application of some form of physical pain in response to undesirable behavior", and "ranges from slapping the hand of a child about to touch a hot stove to identifiable child abuse, such as beatings, scaldings and burnings. Because of this range in the form and severity of punishment, its use as a discipline strategy is controversial".[3] The term "corporal punishment" is often used interchangeably with "physical punishment" or "physical discipline". In the context of causing pain in order to punish, it is distinct from physically restraining a child to protect the child or another person from harm.[5]

It is also shown that the language in which one uses to describe this form of punishment can alleviate the weight or responsibility of the act. Using terms such as "spank" instead of swat, hit, slap, or beat, tends to normalize the actions of corporal punishment. This language allows for the justification of these actions.[6]

Contributing factors

Among various pre-existing factors that influence whether parents use physical punishment are: experience with physical punishment as a child, knowledge about child development, socioeconomic status, parental education and religious ideology. Favorable attitudes toward the use of physical punishment are also a significant predictor of its use.[7] Child-development researcher Elizabeth Gershoff writes that parents are more likely to use physical punishment if:

They strongly favor it and believe in its effectiveness; they were themselves physically punished as children; they have a cultural background, namely their religion, their ethnicity, and/or their country of origin, that they perceive approves of the use of physical punishment; they are socially disadvantaged, in that they have low income, low education, or live in a disadvantaged neighborhood; they are experiencing stress (such as that precipitated by financial hardships or marital conflict), mental health symptoms, or diminished emotional well-being; they report being frustrated or aggravated with their children on a regular basis; they are under 30 years of age; the child being punished is a preschooler (2-5 years old); [or] the child's misbehavior involves hurting someone else or putting themselves in danger.[5]

Parents tend to use corporal punishment on children out of a desire for obedience, both in the short and long term, and especially to reduce children's aggressive behaviors. This despite a significant body of evidence that physically punishing children tends to have the opposite effect, namely, a decrease in long-term compliance and an increase in aggression. Other reasons for parents' use of physical punishment may be to communicate the parent's displeasure with the child, to assert their authority and simple tradition.[1]

Parents also appear to use physical punishment on children as an outlet for anger. The American Academy of Pediatrics notes that "Parents are more likely to use aversive techniques of discipline when they are angry or irritable, depressed, fatigued, and stressed", and estimates that such release of pent-up anger makes parents more likely to hit or spank their children in the future.[3] Furthermore, the effects of poverty, stress, a lack of understanding of children's development, and the need to control one's child are contributing factors to the approval and use of corporal punishments.[8] Parents commonly resort to spanking after losing their temper and most parents surveyed expressed significant feelings of anger, remorse and agitation while physically punishing their children. According to the AAP, "These findings challenge most the notion that parents can spank in a calm, planned manner".[3]

It was also found that a strong contributing factor of parents using corporal punishment is if they believe that it is normative and an expectation of raising a child, or believe it is a necessary part of being a parent. Stress plays a large role in this as well.[8]

Society and culture

In a 2005 study, findings from China, India, Italy, Kenya, the Philippines and Thailand revealed differences in the reported use of corporal punishment, its acceptance in society and its relation to children's social adjustment. Where corporal punishment was perceived as being more culturally accepted, it was less strongly associated with aggression and anxiety in children. However, corporal punishment was still positively associated with child aggression and anxiety in all countries studied.[9] Associations between corporal punishment and increased child aggression have been documented in the countries listed above as well as in Jamaica, Jordan and Singapore, as have links between corporal punishment of children and later antisocial behavior in Brazil, Hong Kong, Jordan, Mongolia, Norway and the United Kingdom. According to Elizabeth Gershoff, these findings appear to challenge the notion that corporal punishment is "good" for children, even in cultures with histories of violence.[1]

Researchers have found that while the use of corporal punishment predicts variation in children's aggression less strongly in countries where there is more social acceptance of it, cultures in which corporal punishment is more accepted have higher overall levels of societal violence.[9]

A 2013 study by Murray A. Straus at the University of New Hampshire found that children across numerous cultures who were spanked committed more crimes as adults than children who were not spanked, regardless of the quality of their relationship to their parents.[10]

Opinions vary across cultures on whether spanking and other forms of physical punishment are appropriate techniques for child-rearing. For example, in the United States and in England, social acceptance of spanking children maintains a majority position, from approximately 61% to 80%.[11][12] In 2020 the Welsh Government banned all form of physical punishment in Wales. In Sweden, before the 1979 ban, more than half of the population considered corporal punishment a necessary part of child rearing. By 1996, the rate was 11%[9] and less than 34% considered it acceptable in a national survey.[13] Elizabeth Gershoff posits that corporal punishment in the United States is largely supported by "a constellation of beliefs about family and child rearing, namely that children are property, that children do not have the right to negotiate their treatment by parents, and that behaviors within families are private".[14]

Social acceptance toward, and prevalence of, corporal punishment by parents in some countries remains high despite a growing scientific consensus that the risks of substantial harm outweigh the potential benefits.[1] Social psychologists posit that this divergence between popular opinion and empirical evidence may be rooted in cognitive dissonance.[15][16][17] In countries such as the US and UK (except Scotland and Wales), spanking is legal but overt child abuse is both illegal and highly stigmatized socially. Because of this, any parent who has ever spanked a child would find it extremely difficult to accept the research findings. If they did acknowledge, even in the smallest way, that spanking was harmful, they would likely feel they are admitting they harmed their own child and thus are a child abuser. Similarly, adults who were spanked as children often face similar cognitive dissonance, because admitting it is harmful might be perceived as accusing their parents of abuse and might also be admitting to having been victimized in a situation where they were helpless to stop it. Such feelings would cause intense emotional discomfort, driving them to dismiss the scientific evidence in favor of weak anecdotal evidence and distorted self-reflection.[16] This is commonly expressed as "I spanked my children and they all turned out fine" or "I was spanked and I turned out fine."[17]

It should be noted, though, that many parenting resources are in fact against physical punishment. Most are in agreement in concluding that through the use of physical punishment, a child learns that violence is acceptable and it is often followed by a negative parent to child relationship as well.[18]

Legality

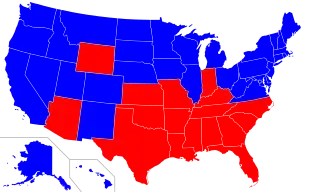

Corporal punishment of minors in the United States

Traditionally, corporal punishment of minor children is legal unless it is explicitly outlawed. According to a 2014 estimate by Human Rights Watch, "Ninety percent of the world's children live in countries where corporal punishment and other physical violence against children is still legal".[19] Many countries' laws provide for a defence of "reasonable chastisement" against charges of assault and other crimes for parents using corporal punishment. The defence is ultimately derived from English law.[20] Due to Nepal banning corporal punishment in September 2018, corporal punishment of children by parents (or other adults) is now banned in 58 countries.[21]

The number of countries banning all forms of corporal punishment against children has grown significantly since the 1989 adoption of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, when only four countries had such bans.[19] Elizabeth Gershoff writes that as of 2008, most of these bans are written into various countries' civil codes, rather than their criminal codes; they largely do not make a special crime of striking a child, but instead establish that assaults against persons of all ages are to be treated similarly. According to Gershoff, the intent of such bans on corporal punishment is not typically to prosecute parents, but to set a higher social standard for caregiving of children.[5]

Religious views

Pope Francis has declared his approval of the use of corporal punishment by parents, as long as punishments do not "demean" children. The Vatican commission appointed to advise the Pope on sexual abuse within the church criticized the Pope for his statement, contending that physical punishments and the infliction of pain were inappropriate methods for disciplining children.[22]

The Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe asserts that "While freedom of religious belief should be respected, such beliefs cannot justify practices which breach the rights of others, including children's rights to respect for their physical integrity and human dignity". They maintain that "Mainstream faith communities and respected leaders are now supporting moves to prohibit and eliminate all violence against children", including corporal punishment.[23] In 2006, a group of 800 religious leaders at the World Assembly of Religions for Peace in Kyoto, Japan endorsed a statement urging governments to adopt legislation banning all corporal punishment of children.[24]: 37

Children's reactions

Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro, referring to the UN Study on Violence Against Children, commented that "Throughout the study process, children have consistently expressed the urgent need to stop all this violence. Children testify to the hurt—not only physical, but 'the hurt inside'—which this violence causes them, compounded by adult acceptance, even approval of it".[24]: 31

According to Bernadette Saunders of Monash University, "Children commonly tell us that physical punishment hurts them physically and can escalate in severity; arouses negative emotions, such as resentment, confusion, sadness, hatred, humiliation, and anger; creates fear and impedes learning; is not constructive, children prefer reasoning; and it perpetuates violence as a means of resolving conflict. Children's comments suggest that children are sensitive to inequality and double standards, and children urge us to respect children and to act responsibly".[25]

When children aged between five and seven in the United Kingdom were asked to describe being smacked by parents, their responses included such remarks as, "it feels like someone banged you with a hammer", "it hurts and it's painful inside—it's like breaking your bones", and "it just feels horrid, you know, and it really hurts, it stings you and makes you horrible inside".[26] Elizabeth Gershoff writes that "The pain and distress evident in these first-hand accounts can accumulate over time and precipitate the mental-health problems that have been linked with corporal punishment".[1] Other comments by children such as, "you [feel] sort of as though you want to run away because they're sort of like being mean to you and it hurts a lot" and "you feel you don't like your parents anymore" are consistent with researchers' concerns that corporal punishment can undermine the quality of parent–child relationships, according to Gershoff.[1]

Relationship to child abuse

The belief that children require physical punishment is among several factors that predispose parents to mistreat their children.[27] Overlapping definitions of physical abuse and physical punishment of children highlight a subtle or non-existent distinction between abuse and punishment.[28] Joan Durrant and Ron Ensom write that most physical abuse is physical punishment "in intent, form, and effect".[29] Incidents of confirmed physical abuse often result from the use of corporal punishment for purposes of discipline, for instance from parents' inability to control their anger or judge their own strength, or from not understanding children's physical vulnerabilities.[9]

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health of the United Kingdom remarked in a 2009 policy statement that "corporal punishment of children in the home is of importance to pediatricians because of its connection with child abuse... all pediatricians will have seen children who have been injured as a result of parental chastisement. It is not possible logically to differentiate between a smack and a physical assault since both are forms of violence. The motivation behind the smack cannot reduce the hurtful impact it has on the child." They assert that preventing child maltreatment is of "vital importance", and advocate a change in the laws concerning corporal punishment. In their words, "Societies which promote the needs and rights of children have a low incidence of child maltreatment, and this includes a societal rejection of physical punishment of children".[30]

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, "The only way to maintain the initial effect of spanking is to systematically increase the intensity with which it is delivered, which can quickly escalate into abuse". They note that "Parents who spank their children are more likely to use other unacceptable forms of corporal punishment".[3]

In the United States, interviews with parents reveal that as many as two thirds of documented instances of physical abuse begin as acts of corporal punishment meant to correct a child's behavior.[1] In Canada, three quarters of substantiated cases of physical abuse of children have occurred within the context of physical punishment, according to the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect.[29] According to Elizabeth Gershoff, "Both parental acts involve hitting, and purposefully hurting, children. The difference between the two is often degree (duration, amount of force, object used) rather than intent".[31]

A 2006 retrospective report study in New Zealand showed that physical punishment of children was quite common in the 1970s and 80s, with 80% of the sample reporting some kind of corporal punishment from parents at some time during childhood. Among this sample, 29% reported being hit with an empty hand, 45% with an object, and 6% were subjected to serious physical abuse. The study noted that abusive physical punishment tended to be given by fathers and often involved striking the child's head or torso instead of the buttocks or limbs.[32]

Clinical and developmental psychologist Diana Baumrind argued in a 2002 paper that parents who are easily frustrated or inclined toward controlling behavior "should not spank", but that existing research did not support a "blanket injunction" against spanking.[33] Gershoff characterized Baumrind et al.'s solution as unrealistic, since it would require potentially abusive parents to monitor themselves. She argues that the burden of proof should be high for advocates of corporal punishment as a disciplinary strategy, asserting that "unless and until researchers, clinicians, and parents can definitively demonstrate the presence of [beneficial] effects of corporal punishment [and] not just the absence of negative effects, we as psychologists cannot responsibly recommend its use".[14]

A 2008 study at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill found that mothers who reported spanking their children were three times more likely to also report using forms of punishment considered abusive to the researchers "such as beating, burning, kicking, hitting with an object somewhere other than the buttocks, or shaking a child less than 2 years old" than mothers who did not report spanking.[34] The authors found that any spanking was associated with increased risk of abuse, and that there were strong associations between abuse and spanking with an object. Adam Zolotor, the study's lead author, noted that "increases in the frequency of spanking are associated with increased odds of abuse, and mothers who report spanking on the buttocks with an object–such as a belt or a switch–are nine times more likely to report abuse".[35]

One study reported by Murray Straus in 2001 found that 40% of 111 mothers surveyed were worried that they could possibly hurt their children by using corporal punishment.[36]

Effects on behavior and development

Numerous studies have found increased risk of impaired child development from the use of corporal punishment.[29] Corporal punishment by parents has been linked to increased aggression, mental health problems, impaired cognitive development, and drug and alcohol abuse.[7][1][29] Many of these results are based on large longitudinal studies controlling for various confounding factors. Joan Durrant and Ron Ensom write that "Together, results consistently suggest that physical punishment has a direct causal effect on externalizing behavior, whether through a reflexive response to pain, modeling, or coercive family processes".[29] Randomized controlled trials, the benchmark for establishing causality, are not commonly used for studying physical punishment because of ethical constraints against deliberately causing pain to study participants. However, one existing randomized controlled trial did demonstrate that a reduction in harsh physical punishment was followed by a significant drop in children's aggressive behavior.[29]

The few existing randomized controlled trials used to investigate physical punishment have shown that it is not more effective than other methods in eliciting children's compliance.[29] A 2002 meta-analysis indicated that spanking did increase children's immediate compliance with parents' commands.[37] However, according to Gershoff, those findings were overly influenced by one study, which found a strong relationship but had a small sample size (only sixteen children studied).[1] A later analysis found that spanking children was not more effective than giving children time-outs in eliciting immediate compliance, and that spanking led to a reduction in long‑term compliance.[31]

Gershoff suggests that corporal punishment may actually decrease a child's "moral internalization" of positive values.[1] According to research, corporal punishment of children predicts weaker internalization of values such as empathy, altruism and resistance to temptation.[38] According to Joan Durrant, it should therefore not be surprising that corporal punishment "consistently predicts increased levels of antisocial behavior in children, including aggression against siblings, peers, and parents, as well as dating violence".[38]

In examining several longitudinal studies that investigated the path from spanking to aggression in children from preschool age through adolescence, Gershoff concluded: "In none of these longitudinal studies did spanking predict reductions in children's aggression [...] Spanking consistently predicted increases in children's aggression over time, regardless of how aggressive children were when the spanking occurred".[31] A 2010 study at Tulane University found a 50% greater risk of aggressive behavior two years later in young children who were spanked more than twice in the month before the study began.[39] The study controlled for a wide variety of confounding variables, including initial levels of aggression in the children. According to the study's leader, Catherine Taylor, this suggests that "it's not just that children who are more aggressive are more likely to be spanked."[40]

A 2002 meta-analytic review by Gershoff that combined 60 years of research on corporal punishment found that corporal punishment was linked with nine negative outcomes in children, including increased rates of aggression, delinquency, mental health problems, problems in relationships with parents, and likelihood of being physically abused.[37] A minority of researchers disagree with these results.[41] Baumrind, Larzelere, and Cowan suggest that the majority of the studies analyzed by Gershoff include "overly severe" forms of punishment and therefore do not sufficiently distinguish corporal punishment from abuse, and that the analysis focused on cross-sectional bivariate correlations.[33] In response, Gershoff points out that corporal punishment in the United States often includes forms, such as hitting with objects, that Baumrind terms "overly severe", and that the line between corporal punishment and abuse is necessarily arbitrary; according to Gershoff "the same dimensions that characterize 'normative' corporal punishment can, when taken to extremes, make hitting a child look much more like abuse than punishment".[14] Another point of contention for Baumrind was the inclusion of studies using the Conflict Tactics Scale, which measures more severe forms of punishment in addition to spanking. According to Gershoff, the Conflict Tactics Scale is "the closest thing to a standard measure of corporal punishment".[14]

A 2005 meta-analysis found that with child noncompliance and antisocial behavior, conditional spanking was favored over most other disciplinary tactics. Including other measurements, customary spanking was found equal to other methods, and only overly severe or predominant usage was found unfavorable.[42] It was suggested that the apparently paradoxical effects are the result of statistical bias in typically used analysis methods, and thus relative comparisons are needed. However, primary usage and severe usage were associated with negative outcomes, and mild spanking still carries the risk of potential escalation into harsh forms.[43]

A 2012 study at the University of Manitoba indicated that people who reported being "pushed, grabbed, shoved, slapped or hit" even "sometimes" as children suffered more mood disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and mania, along with more dependence on drugs or alcohol in adulthood. Those who reported experiencing "severe physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, or exposure to intimate partner violence" were not included in the results. According to the researchers, the findings "provide evidence that harsh physical punishment independent of child maltreatment is related to mental disorders".[44] An earlier Canadian study gave similar results.[45]

Preliminary results from neuroimaging studies suggest that physical punishment involving the use of objects causes a reduction of grey matter in brain areas associated with performance on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale.[29][46] as well as certain alterations to brain regions which secrete or are sensitive to the neurotransmitter dopamine, linked with a risk of drug and alcohol abuse.[29][47]

Corporal punishment also has links with domestic violence. According to Gershoff, research indicates that the more corporal punishment children receive, the more likely they are as adults to act violently towards family members, including intimate partners.[5]

A 2013 meta-analysis by Dr. Chris Ferguson employed an alternative statistical analysis, finding negative cognitive and behavioral effects in children subjected to spanking and corporal punishment, but found the overall relationship to be "trivial" or marginally so with the externalizing effects differing by age. However, Ferguson acknowledged this still indicates potential harmful outcomes and noted some limitations of his analysis, stating "On the other hand, there was no evidence from the current meta-analysis to indicate that spanking or CP held any particular advantages. There appears, from the current data, to be no reason to believe that spanking/CP holds any benefits related to the current outcomes, in comparison to other forms of discipline."[48]

A 2016 meta-analysis of five decades of research found positive associations between being exposed to spanking (defined as "hitting a child on their buttocks or extremities using an open hand") and anti-social behavior, aggression, and mental health problems.[49]

A 2018 meta-analysis found that the apparent effects on child externalizing behavior differ depending on method of analysis.[50] This seems to be the result of a statistical bias in some of the typically used methods.[51][52][53] This may explain the small results found in the 2013 analysis, and the replication of results in other disciplinary tactics.[54] Several subsequent studies have investigated this line of inquiry. One found beneficial effects of only mild spanking after using a more flexible model that accounts for the issues brought up.[55] Others used robustness checks, finding adverse effects of spanking and physical punishment.[56][57][58][59]

A 2021 review of 69 prospective longitudinal studies found that 59% of these studies found adverse effects, 23% found no association, and 17% found mixed effects. The review concluded that: "The evidence is consistent and robust: physical punishment does not predict improvements in child behaviour and instead predicts deterioration in child behaviour and increased risk for maltreatment. There is thus no empirical reason for parents to continue to use physical punishment", and advocated for the banning of physical punishment "in all forms and all settings".[60][61]

Statements by professional associations

The pediatric division of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians has urged that physical punishment of children be outlawed in Australia, stating that is a violation of children's human rights to exempt them from protection against physical assault. They urge support for parents to use "more effective, non-violent methods of discipline".[62][63] The Australian Psychological Society holds that corporal punishment of children is an ineffective method of deterring unwanted behavior, promotes undesirable behaviors and fails to demonstrate an alternative desirable behavior. It asserts that corporal punishment often promotes further undesirable behaviors such as defiance and attachment to "delinquent" peer groups, and encourages an acceptance of aggression and violence as acceptable responses to conflicts and problems.[64]

According to the Canadian Paediatric Society, "The research that is available supports the position that spanking and other forms of physical punishment are associated with negative child outcomes. The Canadian Paediatric Society, therefore, recommends that physicians strongly discourage disciplinary spanking and all other forms of physical punishment".[65]

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health of the United Kingdom opposes corporal punishment of children in all circumstances, stating that "it is never appropriate to hit or beat children".[66] It states that "Corporal punishment [of] children has both short term and long term adverse effects and in principle should not be used since it models an approach which is discouraged between adults".[30] The college advocates legal reform to remove the right of "reasonable punishment" to give children the same legal protections as adults, along with public education directed towards nonviolent parenting methods.[30]

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has stated "parents, other caregivers, and adults interacting with children and adolescents should not use corporal punishment (including hitting and spanking)". It recommends that parents be "encouraged and assisted in the development of methods other than spanking for managing undesired behavior". In a 2018 policy statement, the AAP writes: "corporal punishment to an increased risk of negative behavioral, cognitive, psychosocial, and emotional outcomes for children".[67]

In the AAP's opinion, such punishments, as well as "physical punishment delivered in anger with intent to cause pain", are "unacceptable and may be dangerous to the health and well-being of the child". They also point out that "The more children are spanked, the more anger they report as adults, the more likely they are to spank their own children, the more likely they are to approve of hitting a spouse, and the more marital conflict they experience as adults" and that "spanking has been associated with higher rates of physical aggression, more substance abuse, and increased risk of crime and violence when used with older children and adolescents".[3]

The AAP believes that corporal punishment polarizes the parent–child relationship, reducing the amount of spontaneous cooperation on the part of the child. In their words, "[R]eliance on spanking as a discipline approach makes other discipline strategies less effective to use". The AAP believes that spanking as a form of discipline can easily lead to abuse, noting also that spanking children younger than 18 months of age increases the chance of physical injury.[3]

The United States' National Association of Social Workers "opposes the use of physical punishment in homes, schools, and all other institutions where children are cared for and educated".[68]

Human rights perspectives

Paulo Pinheiro asserts that "The [UN study] should mark a turning point—an end to adult justification of violence against children, whether accepted as 'tradition' or disguised as 'discipline' [...] Children's uniqueness—their potential and vulnerability, their dependence on adults—makes it imperative that they have more, not less, protection from violence".[24]: 16 His report to the General Assembly of the United Nations recommends prohibition of all forms of violence against children, including corporal punishment in the family and other settings.[24]: 16

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child remarked in 2006 that all forms of corporal punishment, along with non-physical punishment which "belittles, humiliates, denigrates, scapegoats, threatens, scares or ridicules" children were found to be "cruel and degrading" and therefore incompatible with the Convention on the Rights of the Child. In the committee's view, "Addressing the widespread acceptance or tolerance of corporal punishment of children and eliminating it, in the family, schools and other settings, is not only an obligation of States parties under the Convention. It is also a key strategy for reducing and preventing all forms of violence in societies".[69]

The Committee on the Rights of the Child advocates legal reform banning corporal punishment that is educational rather than punitive:

The first purpose of law reform to prohibit corporal punishment of children within the family is prevention: to prevent violence against children by changing attitudes and practice, underlining children's right to equal protection and providing an unambiguous foundation for child protection and for the promotion of positive, non-violent and participatory forms of child-rearing [...] While all reports of violence against children should be appropriately investigated and their protection from significant harm assured, the aim should be to stop parents from using violent or other cruel or degrading punishments through supportive and educational, not punitive, interventions.[69]

The office of Europe's Commissioner for Human Rights notes that the defence of "reasonable chastisement" is based on the view that children are property, equating it with former legal rights of husbands to beat wives and masters to beat servants. The Commissioner stresses that human rights, including the right to physical integrity, are the primary consideration in advocating an end to corporal punishment:

The imperative for removing adults' assumed rights to hit children is that of human rights principles. It should therefore not be necessary to prove that alternative and positive means of socializing children are more effective. However, research into the harmful physical and psychological effects of corporal punishment in childhood and later life and into the links with other forms of violence do indeed add further compelling arguments for banning the practice and thereby breaking the cycle of violence.[23]

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe maintains that corporal punishment is a breach of children's "fundamental right to human dignity and physical integrity", and violates children's "equally fundamental right to the same legal protection as adults". The Assembly urges a total ban on "all forms of corporal punishment and any other forms of degrading punishment or treatment of children" as a requirement of the European Social Charter.[70] The European Court of Human Rights has found corporal punishment to be a violation of children's rights under the European Convention on Human Rights, stating that bans on corporal punishment did not violate religious freedom or the right to private or family life.[70]

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights concluded in 2009 that corporal punishment "constitutes a form of violence against children that wounds their dignity and hence their human rights", asserting that "the member states of the Organization of American States are obliged to guarantee children and adolescents special protection against the use of corporal punishment".[71]

UNESCO also recommends that corporal punishment be prohibited in schools, homes and institutions as a form of discipline, and contends that it is a violation of human rights as well as counterproductive, ineffective, dangerous and harmful to children.[72]

Prohibition

The 1979 Swedish ban

Sweden was the world's first nation to outlaw all forms of corporal punishment of children. In 1957, the section permitting parents to use force in reprimanding their children (as long as it did not cause any severe injury) was completely removed from the Penal Code. The intent of this change was to provide children with the same protection from assault that adults receive and to clarify the grounds for criminal prosecution of parents who abused their children. However, parents' right to use corporal punishment of their children was not eliminated; until 1966, parents might use mild forms of physical discipline that would not constitute assault under the Penal Code. In 1966, the section permitting parents to use physical discipline was removed and fully replaced by the constitution of assault under the Penal Code.[73]

Even though parents' right to use corporal punishment of their children was no longer supported by law, many parents believed the law allowed it. Therefore, it was necessary with a more clear law which supported children's rights and protected children from violence or other humiliating treatment. On 1 July 1979, Sweden became the world's first nation to explicitly ban corporal punishment of children through an amendment to the Parenthood and Guardianship Code which stated:

Children are entitled to care, security and a good upbringing. Children are to be treated with respect for their person and individuality and may not be subjected to corporal punishment or any other humiliating treatment.[74]

Some critics in the Swedish Parliament predicted that the amendment would lead to a large-scale criminalization of Swedish parents. Others asserted that the law contradicted the Christian faith. Despite these objections, the law received almost unanimous support in Parliament. The law was accompanied by a public education campaign by the Swedish Ministry of Justice, including brochures distributed to all households with children, as well as informational posters and notices printed on milk cartons.[75]

One thing that helped pave the way for the ban was a 1971 murder case where a 3-year-old girl was beaten to death by her stepfather. The case shook the general public and preventing child abuse became a political hot topic for years to come.[76]

In 1982, a group of Swedish parents brought a complaint to the European Commission of Human Rights asserting that the ban on parental physical punishment breached their right to respect for family life and religious freedom; the complaint was dismissed.[77]

According to the Swedish Institute, "Until the 1960s, nine out of ten preschool children in Sweden were spanked at home. Slowly, though, more and more parents voluntarily refrained from its use and corporal punishment was prohibited throughout the educational system in 1958". As of 2014, approximately 5 percent of Swedish children are spanked illegally.[78]

In Sweden, professionals working directly with children are obliged to report any suggestion of maltreatment to social services. Allegations of assault against children are frequently handled in special "children's houses", which combine the efforts of police, prosecutors, social services, forensic scientists and child psychologists. The Children and Parents Code does not itself impose penalties for smacking children, but instances of corporal punishment that meet the criteria of assault may be prosecuted.[79]

From the 1960s to the 2000s, there was a steady decline in the numbers of parents who use physical punishment as well as those who believe in its use. In the 1960s, more than 90 percent of Swedish parents reported using physical punishment, even though only approximately 55 percent supported its use. By the 2000s, the gap between belief and practice had nearly disappeared, with slightly more than 10 percent of parents reporting that they use corporal punishment. In 1994, the first year that Swedish children were asked to report their experiences of corporal punishment, 35 percent said they had been smacked at some point. According to the Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, this number was considerably lower after the year 2000. Interviews with parents also revealed a sharp decline in more severe forms of punishment, such as punching or the use of objects to hit children, which are likely to cause injury.[80]

The Ministry of Health and Social Affairs and Save the Children ascribe these changes to a number of factors, including the development of Sweden's welfare system; greater equality between the sexes and generations than elsewhere in the world; the large number of children attending daycare centers, which facilitate the identification of children being mistreated; and efforts by neonatal and children's medical clinics to reduce family violence.[81]

While cases of suspected assault on children have risen since the early 1980s, this rise can be attributed to an increase in reporting due to reduced tolerance of violence against children, rather than an increase in actual assaults. Since the 1979 ban on physical punishment, the percentage of reported assaults that result in prosecution has not increased; however, Swedish social services investigate all such allegations and provide supportive measures to the family where needed.[82]

According to Joan Durrant, the ban on corporal punishment was intended to be "educational rather than punitive".[83] After the 1979 change to the Parenthood and Guardianship Code, there was no increase in the number of children removed from their families; in fact, the number of children entering state care significantly decreased. There have also been more social-service interventions done with parental consent and fewer compulsory interventions.[83] Durrant writes that the authorities had three goals, namely: to bring about a change in public attitudes away from support for corporal punishment, to facilitate the identification of children likely to be physically abused, and to enable earlier intervention in families with the intention of supporting, rather than punishing, parents. According to Durrant, data from various official sources in Sweden show that these goals are being met.[84] She writes:

Since 1981, reports of assaults against children in Sweden have increased—as they have worldwide, following the 'discovery' of child abuse. However, the proportion of suspects who are in their twenties, and therefore raised in a no-smacking culture, has decreased since 1984, as has the proportion born in the Nordic nations with corporal punishment bans.[83]

Contrary to expectations of an increase of juvenile delinquency following the ban of corporal punishment, youth crime remained steady while theft convictions and suspects in narcotics crimes among Swedish youth significantly decreased; youth drug and alcohol use and youth suicide also decreased. Durrant writes: "While drawing a direct causal link between the corporal punishment ban and any of these social trends would be too simplistic, the evidence presented here indicates that the ban has not had negative effects".[83]

Further research has shown no sign of a rise in crimes by young people. From the mid-1990s into the 2000s, youth crime decreased, primarily owing to fewer instances of theft and vandalism, while violent crime remained constant. Most young people in Sweden who commit offences do not become habitual criminals, according to the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs.[85] While there has been an increase in reports of assaults by youth against others of similar age, official sources indicate that the increase has been largely due to a "zero-tolerance" approach to school bullying resulting in increased reporting, rather than an increase in actual assaults.[5][84]

After Sweden: bans around the world

As of 2023 the following countries and territories have (or are planned to have) completely prohibited corporal punishment of children:

Sweden (1979)

Sweden (1979) Finland (1983)

Finland (1983) Austria (1989)

Austria (1989) People's Republic of China (1991)

People's Republic of China (1991) Cyprus (1994)

Cyprus (1994) Denmark (1997)

Denmark (1997) Poland (1997)

Poland (1997) Latvia (1998)

Latvia (1998) Croatia (1999)

Croatia (1999) Bulgaria (2000)

Bulgaria (2000) Israel (2000)[86][87][88]

Israel (2000)[86][87][88] Germany (2000)

Germany (2000) Turkmenistan (2002)

Turkmenistan (2002) Iceland (2003)

Iceland (2003) Ukraine (2004)

Ukraine (2004) Romania (2004)

Romania (2004) Hungary (2005)

Hungary (2005) Greece (2006)

Greece (2006) Netherlands (2007)

Netherlands (2007) New Zealand (2007)

New Zealand (2007) Portugal (2007)

Portugal (2007)

Uruguay (2007)

Uruguay (2007) Venezuela (2007)

Venezuela (2007) Chile (2007)[89]

Chile (2007)[89] Spain (2007)[90][91][92][93]

Spain (2007)[90][91][92][93] Togo (2007)

Togo (2007) Costa Rica (2008)

Costa Rica (2008) Moldova (2008)

Moldova (2008) Luxembourg (2008)

Luxembourg (2008) Liechtenstein (2008)

Liechtenstein (2008) Norway (2010)

Norway (2010) Tunisia (2010)

Tunisia (2010) Kenya (2010)

Kenya (2010) Congo, Republic of (2010)

Congo, Republic of (2010) Albania (2010)

Albania (2010) South Sudan (2011)

South Sudan (2011) North Macedonia (2013)

North Macedonia (2013) Cabo Verde (2013)

Cabo Verde (2013) Honduras (2013)

Honduras (2013) Malta (2014)

Malta (2014) Brazil (2014)

Brazil (2014).svg.png.webp) Bolivia (2014)

Bolivia (2014) Argentina (2014)

Argentina (2014) San Marino (2014)

San Marino (2014) Nicaragua (2014)

Nicaragua (2014) Estonia (2014)

Estonia (2014) Andorra (2014)

Andorra (2014) Benin (2015)

Benin (2015) Ireland (2015)

Ireland (2015) Peru (2015)

Peru (2015) Mongolia (2016)

Mongolia (2016) Montenegro (2016)

Montenegro (2016) Paraguay (2016)

Paraguay (2016) Aruba (2016)[94]

Aruba (2016)[94] Slovenia (2016)

Slovenia (2016) Lithuania (2017)

Lithuania (2017) Nepal (2018)

Nepal (2018) Kosovo (2019)

Kosovo (2019) France (2019)[95]

France (2019)[95] South Africa (2019)

South Africa (2019) Jersey (2019)

Jersey (2019) Japan (2020)[96]

Japan (2020)[96] Georgia (2020)[97]

Georgia (2020)[97] Scotland (2020)

Scotland (2020) Seychelles (2020)[98]

Seychelles (2020)[98] Guinea (2021)

Guinea (2021) Colombia (2021)

Colombia (2021) South Korea (2021)[99][100][101]

South Korea (2021)[99][100][101] Wales (2022)[102][103]

Wales (2022)[102][103] Zambia (2022)[104]

Zambia (2022)[104] Mauritius (2022)

Mauritius (2022) Philippines (2023)

Philippines (2023)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Gershoff, Elizabeth T. (Spring 2010). "More Harm Than Good: A Summary of Scientific Research on the Intended and Unintended Effects of Corporal Punishment on Children". Law & Contemporary Problems. Duke University School of Law. 73 (2): 31–56.

- ↑ Afifi, T. O.; Mota, N. P.; Dasiewicz, P.; MacMillan, H. L.; Sareen, J. (2 July 2012). "Physical Punishment and Mental Disorders: Results From a Nationally Representative US Sample". Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). 130 (2): 184–192. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2947. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 22753561. S2CID 21759236.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health (April 1998). "Guidance for effective discipline". Pediatrics. 101 (4 Pt 1): 723–8. doi:10.1542/peds.101.4.723. PMID 9521967. S2CID 79545678.

- 1 2 Pinheiro, Paulo Sérgio (2006). "Violence against children in the home and family". World Report on Violence Against Children. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Secretary-General's Study on Violence Against Children. ISBN 978-92-95057-51-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gershoff, E.T. (2008). Report on Physical Punishment in the United States: What Research Tells Us About Its Effects on Children (PDF). Columbus, OH: Center for Effective Discipline. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ↑ Brown, Alan S.; Holden, George W.; Ashraf, Rose (January 2018). "Spank, slap, or hit? How labels alter perceptions of child discipline". Psychology of Violence. 8 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1037/vio0000080. ISSN 2152-081X. S2CID 152058445.

- 1 2 Ateah, C. A.; Secco, M. L.; Woodgate, R. L. (2003). "The risks and alternatives to physical punishment use with children". J Pediatr Health Care. 17 (3): 126–32. doi:10.1067/mph.2003.18. PMID 12734459.

- 1 2 Chiocca, Ellen M. (1 May 2017). "American Parents' Attitudes and Beliefs About Corporal Punishment: An Integrative Literature Review". Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 31 (3): 372–383. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.01.002. ISSN 0891-5245. PMID 28202205.

- 1 2 3 4 "Corporal Punishment" (2008). International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences.

- ↑ "College students more likely to be lawbreakers if spanked as children". Science Daily. 22 November 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ↑ Reaves, Jessica (5 October 2000). "Survey Gives Children Something to Cry About". Time. New York. Archived from the original on 15 March 2004. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ↑ Bennett, Rosemary (20 September 2006). "Majority of parents admit to smacking children". The Times. London. Retrieved 2 February 2010. (subscription required)

- ↑ Statistics Sweden. (1996). Spanking and other forms of physical punishment. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden.

- 1 2 3 4 Gershoff, Elizabeth T. (2002). "Corporal Punishment, Physical Abuse, and the Burden of Proof: Reply to Baumrind, Larzelere, and Cowan (2002), Holden (2002), and Parke (2002)". Psychological Bulletin. 128 (4): 602–611. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.602.

- ↑ Sanderson, Catherine Ashley (2010). Social psychology. Hoboken, NJ.: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-25026-5.

- 1 2 Marshall, Michael J. (2002). Why spanking doesn't work: stopping this bad habit and getting the upper hand on effective discipline. Springville, Utah: Bonneville Books. ISBN 978-1-55517-603-7.

- 1 2 Kirby, Gena. "Confessions of an AP Mom Who Spanked - Progressive Parenting". Archived from the original on 28 November 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Baker, Amy J. L.; LeBlanc, Stacie Schrieffer; Schneiderman, Mel (2021). "Do Parenting Resources Sufficiently Oppose Physical Punishment?: A Review of Books, Programs, and Websites". Child Welfare. 99 (2): 77–98. JSTOR 48623720. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- 1 2 "25th Anniversary of the Convention on the Rights of the Child". Human Rights Watch. 17 November 2014.

- ↑ "Legal defences for corporal punishment of children derived from English law" (PDF). Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. 10 November 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ↑ "States which have prohibited all corporal punishment". Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. Archived from the original on 19 December 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ↑ Laine, Samantha (7 February 2015), "Spanking OK? Why Vatican sex abuse commission disagrees with Pope", Christian Science Monitor

- 1 2 Commissioner for Human Rights (January 2008). "Children and corporal punishment: 'The right not to be hit, also a children's right'". coe.int. Council of Europe.

- 1 2 3 4 Abolishing Corporal Punishment of Children: Questions and answers (PDF). Strasbourg: Council of Europe. 2007. ISBN 978-9-287-16310-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2014.

- ↑ Saunders, B. J. (2013). "Ending the physical punishment of children in the English speaking world:The impact of language, tradition and law". International Journal of Children's Rights. 21 (2): 278–304. doi:10.1163/15718182-02102001.

- ↑ Willow, Carolyne; Hyder, Tina (1998). It Hurts You Inside: Children talking about smacking. London: National Children's Bureau. pp. 46, 47. ISBN 978-1905818617.

- ↑ Lamanna, Mary Ann; Riedmann, Agnes; Stewart, Susan D. (2016). Marriages, Families, and Relationships: Making Choices in a Diverse Society. Boston, Mass.: Cengage Learning. p. 318. ISBN 978-1-337-10966-6.

- ↑ Saunders, Bernadette; Goddard, Chris (2010). Physical Punishment in Childhood: The Rights of the Child. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-470-72706-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Durrant, Joan; Ensom, Ron (4 September 2012). "Physical punishment of children: lessons from 20 years of research". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 184 (12): 1373–1377. doi:10.1503/cmaj.101314. PMC 3447048. PMID 22311946.

- 1 2 3 "Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health Position Statement on corporal punishment" (PDF). November 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 Gershoff, Elizabeth T. (September 2013). "Spanking and Child Development: We Know Enough Now to Stop Hitting Our Children". Child Development Perspectives. 7 (3): 133–137. doi:10.1111/cdep.12038. PMC 3768154. PMID 24039629.

- ↑ Millichamp, Jane; Martin J; Langley J (2006). "On the receiving end: young adults describe their parents' use of physical punishment and other disciplinary measures during childhood". The New Zealand Medical Journal. 119 (1228): U1818. PMID 16462926.

- 1 2 Baumrind, Diana; Cowan, P.; Larzelere, Robert (2002). "Ordinary Physical Punishment: Is It Harmful?". Psychological Bulletin. 128 (4): 580–58. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.580. PMID 12081082.

- ↑ Zolotor A.J.; Theodore A.D.; Chang J.J.; Berkoff M.C.; Runyan D.K. (October 2008). "Speak softly--and forget the stick. Corporal punishment and child physical abuse". Am J Prev Med. 35 (4): 364–9. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.031. PMID 18779030.

- ↑ "UNC study shows link between spanking and physical abuse". UNC School of Medicine. 19 August 2008.

- ↑ Straus, Murray, Beating the Devil out of Them: Corporal Punishment in American Families and Its Effects on Children. Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick, New Jersey, 2001: 85. ISBN 0-7658-0754-8

- 1 2 Gershoff E.T. (July 2002). "Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: a meta-analytic and theoretical review". Psychol Bull. 128 (4): 539–79. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.539. PMID 12081081. S2CID 2393109.

- 1 2 Durrant, Joan (March 2008). "Physical Punishment, Culture, and Rights: Current Issues for Professionals". Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 29 (1): 55–66. doi:10.1097/DBP.0b013e318135448a. PMID 18300726. S2CID 20693162.

- ↑ Taylor, CA.; Manganello, JA.; Lee, SJ.; Rice, JC. (May 2010). "Mothers' spanking of 3-year-old children and subsequent risk of children's aggressive behavior". Pediatrics. 125 (5): e1057–65. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2678. PMC 5094178. PMID 20385647.

- ↑ Park, Alice (3 May 2010). "The Long-Term Effects of Spanking". Time. New York. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Smith, Brendan L. (April 2012). "The Case Against Spanking". Monitor on Psychology. American Psychological Association. 43 (4): 60. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ↑ Larzelere, R. E.; Kuhn, B. R. (2005). "Comparing Child Outcomes of Physical Punishment and Alternative Disciplinary Tactics: A Meta-Analysis". Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 8 (1): 1–37. doi:10.1007/s10567-005-2340-z. PMID 15898303. S2CID 34327045.

- ↑ Lansford, Jennifer E.; Wager, Laura B.; Bates, John E.; Pettit, Gregory S.; Dodge, Kenneth A. (2012). "Forms of Spanking and Children's Externalizing Behaviors". Family Relations. 61 (2): 224–236. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00700.x. PMC 3337708. PMID 22544988.

- ↑ Smith, Michael (2 July 2012). "Spanking Kids Leads to Adult Mental Illnesses". ABC News.

- ↑ MacMillan H.L.; Boyle M.H.; Wong M.Y.; Duku E.K.; Fleming J.E.; Walsh C.A. (October 1999). "Slapping and spanking in childhood and its association with lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a general population sample". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 161 (7): 805–9. PMC 1230651. PMID 10530296.

- ↑ Tomoda, Akemi; Suzuki, Hanako; Rabi, Keren; Sheu, Yi-Shin; Polcari, Ann; Teicher, Martin H. (2009). "Reduced prefrontal cortical gray matter volume in young adults exposed to harsh corporal punishment". NeuroImage. 47 (Suppl 2): T66–T71. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.03.005. PMC 2896871. PMID 19285558.

- ↑ Sheu, Y. S.; Polcari, A.; Anderson, C. M.; Teicher, M. H. (2010). "Harsh corporal punishment is associated with increased T2 relaxation time in dopamine-rich regions". NeuroImage. 53 (2): 412–419. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.043. PMC 3854930. PMID 20600981.

- ↑ Ferguson, C. J. (2013). "Spanking, corporal punishment and negative long-term outcomes: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies". Clinical Psychology Review. 33 (1): 196–208. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.11.002. PMID 23274727.

- ↑ Gershoff, Elizabeth T.; Grogan-Kaylor, Andrew (2016). "Spanking and Child Outcomes: Old Controversies and New Meta-Analyses" (PDF). Journal of Family Psychology. 30 (4): 453–469. doi:10.1037/fam0000191. PMC 7992110. PMID 27055181.

- ↑ Larzelere, R. E.; Gunnoe, M. L.; Ferguson, C. J. (2018). "Improving Causal Inferences in Meta-analyses of Longitudinal Studies: Spanking as an Illustration". Child Dev. 89 (6): 2038–2050. doi:10.1111/cdev.13097. PMID 29797703.

- ↑ Larzelere, R. E.; Lin, H.; Payton, M. E.; Washburn, I. J. (2018). "Longitudinal biases against corrective actions". Archives of Scientific Psychology. 6 (1): 243–250. doi:10.1037/arc0000052.

- ↑ Larzelere, R. E.; Cox, R. B. (2013). "Making Valid Causal Inferences About Corrective Actions by Parents From Longitudinal Data". J Fam Theory Rev. 5 (4): 282–299. doi:10.1111/jftr.12020.

- ↑ Berry, D.; Willoughby, M. T. (2017). "On the Practical Interpretability of Cross-Lagged Panel Models: Rethinking a Developmental Workhorse". Child Dev. 88 (4): 1186–1206. doi:10.1111/cdev.12660. PMID 27878996.

- ↑ Larzelere, R. E.; Cox, R. B.; Smith, G. L. (2010). "Do nonphysical punishments reduce antisocial behavior more than spanking? A comparison using the strongest previous causal evidence against spanking". BMC Pediatrics. 10 (1): 10. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-10-10. PMC 2841151. PMID 20175902.

- ↑ Pritsker, Joshua (2021). "Spanking and externalizing problems: Examining within-subject associations". Child Development. 92 (6): 2595–2602. doi:10.1111/cdev.13701. PMID 34668581. S2CID 239034688.

- ↑ Cuartas, Jorge (2021). "The effect of spanking on early social-emotional skills". Child Development. 93 (1): 180–193. doi:10.1111/cdev.13646. PMID 34418073. S2CID 237260610.

- ↑ Cuartas, Jorge; Grogan-Kaylor, A; Gershoff, Elizabeth (2020). "Physical punishment as a predictor of early cognitive development: Evidence from econometric approaches". Developmental Psychology. 56 (11): 2013–2026. doi:10.1037/dev0001114. PMC 7983059. PMID 32897084.

- ↑ Kang, Jeehye (2022). "Spanking and children's social competence: Evidence from a US kindergarten cohort study". Child Abuse & Neglect. 132: 105817. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105817. PMID 35926250. S2CID 251273284.

- ↑ Kang, Jeehye (2022). "Spanking and children's early academic skills: Strengthening causal estimates". Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 61: 47–57. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2022.05.005. S2CID 249417752.

- ↑ "Evidence against physically punishing kids is clear, researchers say". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ↑ Heilmann, Anja; Mehay, Anita; Watt, Richard G; Kelly, Yvonne; Durrant, Joan E; van Turnhout, Jillian; Gershoff, Elizabeth T (2021). "Physical punishment and child outcomes: a narrative review of prospective studies". The Lancet. Elsevier BV. 398 (10297): 355–364. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00582-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 8612122. PMID 34197808. S2CID 235665014.

- ↑ White, Cassie (29 August 2013). "Why doctors are telling us not to smack our children". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ↑ "Position Statement: Physical Punishment of Children" (PDF). Royal Australasian College of Physicians, Paediatric & Child Health Division. July 2013. pp. 4, 6–7.

- ↑ "Legislative assembly questions #0293 – Australian Psychological Society: Punishment and Behaviour Change". Parliament of New South Wales. 30 October 1996. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- ↑ Psychosocial Paediatrics Committee; Canadian Paediatric Society (2004). "Effective discipline for children". Paediatrics & Child Health. 9 (1): 37–41. doi:10.1093/pch/9.1.37. PMC 2719514. PMID 19654979. Archived from the original on 25 January 2009. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- ↑ Lynch M. (September 2003). "Community pediatrics: role of physicians and organizations". Pediatrics. 112 (3 Part 2): 732–734. doi:10.1542/peds.112.S3.732. PMID 12949335. S2CID 35761650.

- ↑ Sege, Robert D.; Siegel, Benjamin S.; AAP Council on Child Abuse And Neglect; AAP Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health (2018). "Effective Discipline to Raise Healthy Children" (PDF). Pediatrics. 142 (6). e20183112. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3112. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 30397164. S2CID 53239513.

- ↑ Social Work Speaks: NASW Policy Statements (Eighth ed.). Washington, D.C.: NASW Press. 2009. pp. 252–258. ISBN 978-0-87101-384-2.

- 1 2 "General comment No. 8 (2006): The right of the child to protection from corporal punishment and or cruel or degrading forms of punishment (articles 1, 28(2), and 37, inter alia)". United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, 42nd Sess., U.N. Doc. CRC/C/GC/8. 2 March 2007.

- 1 2 "Recommendation 1666 (2004): Europe-Wide Ban on Corporal Punishment of Children". Parliamentary Assembly, Council of Europe (21st Sitting). 23 June 2004.

- ↑ Report on Corporal Punishment and Human Rights of Children and Adolescents (PDF), Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Rapporteurship on the Rights of the Child, Organization of American States, 5 August 2009, p. 38

- ↑ Hart, Stuart N.; et al. (2005). Eliminating Corporal Punishment: The Way Forward to Constructive Child Discipline. Education on the move. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 64–71. ISBN 978-92-3-103991-1.

- ↑ Durrant, Joan E. (1996). "The Swedish Ban on Corporal Punishment: Its History and Effects". In Frehsee, Detlev; et al. (eds.). Family Violence Against Children: A Challenge for Society. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 20. ISBN 978-3-11-014996-8.

- ↑ Modig, Cecilia (2009). Never Violence – Thirty Years on from Sweden's Abolition of Corporal Punishment (PDF). Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, Sweden; Save the Children Sweden. Reference No. S2009.030. p. 14.

- ↑ Modig (2009), p. 13.

- ↑ "How Sweden became the first country in the world to ban corporal punishment - Radio Sweden". Sveriges Radio. July 2015.

- ↑ Seven Individuals v Sweden, European Commission of Human Rights, Admissibility Decision, 13 May 1982.

- ↑ "First Ban on Smacking Children". Swedish Institute. 2 December 2014.

- ↑ Modig (2009), pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Modig (2009), pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Modig (2009), pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Modig (2009), p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 Durrant, Joan E. (2000). A Generation Without Smacking: The impact of Sweden's ban on physical punishment (PDF). London: Save the Children. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-84-187019-9.

- 1 2 Durrant (2000), p. 27.

- ↑ Modig (2009), p. 22.

- ↑ Izenberg, Dan (26 January 2000). "Israel Bans Spanking". The Natural Child Project. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ↑ Ezer, Tamar (January 2003). "Children's Rights in Israel: An End to Corporal Punishment?". Oregon Review of International Law. 5: 139. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ↑ Corporal punishment of children in Israel (PDF) (Report). GITEACPOC. February 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ↑ "CRIN". 25 July 2023.

- ↑ "Spain bans parents from smacking children". Reuters. Thomson Reuters. 20 December 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ↑ Sosa Troya, María (16 April 2021). "Spain approves pioneering child protection law". El País. PRISA. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ↑ "El Congreso aprueba la ley de protección a la infancia con la única oposición de Vox". Público (in Spanish). Mediapro. 16 April 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ↑ Corporal punishment of children in Spain (PDF) (Report). GITEACPOC. June 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ↑ "Aruba has prohibited all corporal punishment of children - Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children". Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ↑ "France bans parents from using corporal punishment to discipline children". 3 July 2019.

- ↑ "Japan prohibits all corporal punishment of children | Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children".

- ↑ "Georgia | Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children".

- ↑ "President Assents to Legislation: Children (Amendment) Act, 2020 and Defence (Amendment) Act, 2020".

- ↑ "S. Korea joins list of countries that ban corporal punishment of children". The Hankyoreh. Jung Yung-mu. 11 January 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ↑ "Republic of Korea prohibits all corporal punishment of children". End Violence Against Children. 25 March 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ↑ "Republic of Korea bans corporal punishment". end-violence.org.

- ↑ "Wales to bring in smacking ban after assembly vote". BBC News. 28 January 2020.

- ↑ "Wales introduces ban on smacking and slapping children". The Guardian. 21 March 2022.

- ↑ "Zambia prohibits all corporal punishment!". 8 November 2022.

External links

- Equally Protected? A review of the evidence on the physical punishment of children, NSPCC Scotland, Children 1st, Barnardo's Scotland, Children and Young People's Commissioner Scotland

- Joint Statement on Physical Punishment of Children and Youth, Coalition on Physical Punishment of Children and Youth (Canada)

- International Save the Children Alliance position on corporal punishment Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine