45°22′1″N 64°20′18″W / 45.36694°N 64.33833°W

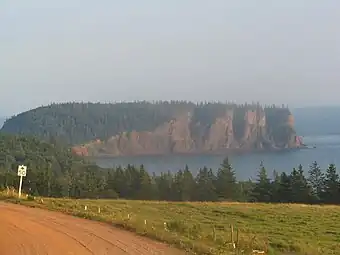

Partridge Island is a significant historical, cultural and geological site located near the mouth of Parrsboro Harbour and the town of Parrsboro on the Minas Basin, in Cumberland County, Nova Scotia, Canada. It attracts many visitors including sightseers, swimmers, photographers, hikers and amateur geologists.[1] Partridge Island is actually a peninsula that is connected to the mainland by a sandbar isthmus.[2] According to local legend, the isthmus was created during the Saxby Gale of 1869.[3][4] The hiking trail to the top of the island affords scenic views of key landforms on the Minas Basin including Cape Blomidon, Cape Split and Cape Sharp.[5] The nearby Ottawa House By-the-Sea Museum contains artifacts and exhibits illustrating the history of the former village at Partridge Island, which dates from the 1770s.[6] Partridge Island is a favourite hunting ground for rockhounds because its ancient sandstone and basalt cliffs are steadily eroded by the fast-moving currents of the world's highest tides. Rocks and debris worn away from its cliffs are dragged down the beach making it possible to find gemstones, exotic-looking zeolite minerals and fossils.[7] Fossil hunters are warned, however, that although one or two loose specimens may be collected, Nova Scotia law requires that they be sent or taken to a museum for further study, and no fossils may be excavated from bedrock without a permit.[8]

Myth and legend

Partridge Island apparently got its name from a European translation of pulowech, the Mi'kmaq word for partridge.[9] The Confederacy of Mainland Mi'kmaq report that the Mi’kmaq themselves called Partridge Island "Wa’so’q," which means “Heaven" because the island was a traditional place for gathering the sacred stone amethyst. It was also the mythic home of the grandmother of the legendary Mi'kmaq god-giant Glooscap.[10] According to Mi'kmaq artist and storyteller, Gerald Gloade, the natives also called Partridge Island "Glooscap's grandmother's cooking pot" because the waters around the island appear to boil twice a day when air trapped in holes in the basalt is pushed out as the tide rises.[11]

Legend has it that Glooscap lived on Cape Blomidon, across the basin from Partridge Island. His heroic exploits account for key features of the landscape, including perhaps, the dramatic tides of the Minas Basin. When his enemy, Beaver, built a dam across the Minas Channel from Cape Split to the Cumberland side, the waters not only flooded Glooscap's herbal medicine garden at Advocate Harbour, they inundated the Annapolis Valley. Glooscap arrived on the scene, saw what the Beaver had done, and angrily smashed the dam with his paddle releasing the pent-up waters.[12] According to anthropologist Anne-Christine Hornborg, the daily breaking and re-building of a giant beaver dam serves as a metaphor for the powerful tides of the Minas Basin — not a literal explanation, but a symbolic representation of the natural environment.[13]

Early history

For aboriginal peoples and later European settlers, Partridge Island was an important sea link to other parts of Nova Scotia because of its location at one of the narrowest points on the Minas Basin. The Mi'kmaq name for the settlement at Partridge Island was Awokum, which means crossing-over point or short cut. In the 1730s, two French settlers, John Bourg and Francis Arseneau, operated a ferry service that crossed the basin from Partridge Island.[14][15]

An interpretive panel at the top of the Partridge Island hiking trail notes that many of Canada's earliest historical events could have been witnessed from its heights overlooking the Minas Basin. They include the arrival in ancient times of Nova Scotia's aboriginal peoples; the appearance in 1607 of the French explorer, Samuel de Champlain, who called the Minas Basin, Le Bassin des Mines, as he searched for copper in the red sandstone cliffs; the voyage in 1672 of the first Acadian settlers who sailed by Partridge Island on their way to dyke and farm tidal marshlands across the basin; the arrival in 1755 of the British colonial flotilla that began to forcibly deport the Acadians and in the 1760s, the arrival of New England Planters who settled the vacated Acadian lands.[5][14][16]

Military and commercial significance

The village of Partridge Island, established in the 1770s, was the original site of the town that would later become Parrsboro. Its military blockhouse on a high hill overlooking the village was strategically important thanks to a protected, deep-water anchorage and an excellent view of potentially hostile ships plying the Minas Basin. After ferry service was re-established in 1764, Partridge Island continued to be an important link in the sea route to other parts of Nova Scotia, including the capital, Halifax.[14] During the American Revolutionary War, a U.S. privateer captured the Partridge Island ferry cutting communications at a time when American Patriots led by Jonathan Eddy were laying siege to Fort Cumberland, near the present-day Amherst. British forces soon recaptured the ferry and ended Eddy's siege ensuring Nova Scotia would remain loyal to Britain.[17] The Partridge Island blockhouse was also reinforced with military weaponry, including brass cannons, during the War of 1812.[4] Partridge Island prospered during the latter part of the 18th century. The village boasted an inn and a tavern as well as a store, school and church as it became a flourishing trading centre. Ships from all over the world anchored there delivering goods to the store operated by the family of James Ratchford which, in turn, supplied every town and village on the Minas Basin with manufactured products.[14]

Many factors contributed to the village's eventual decline, but politics played a significant part. The Ratchfords were staunch Conservatives. After Joseph Howe became the Liberal premier of Nova Scotia, the post office and the customs house moved to Mill Village, site of the present-day Town of Parrsboro, about three kilometres (2 miles) to the northeast. Ratchford's death in 1836 accelerated the shift to the new settlement, even though Conservative Member of Parliament, Sir Charles Tupper, later tried to reinforce Partridge Island's status by successfully pushing for the construction of a large ferry wharf, which soon became known as "Tupper's Snag." Tupper also purchased the Ratchford home, renaming it Ottawa House, to show his support for Canadian Confederation.[4][14] Today, there is little left of the Partridge Island settlement, although the historic Ratchford/Tupper home is still there, operating as the Ottawa House By-the-Sea Museum.[6]

Geology and gems

Partridge Island stands at the edge of the ancient rift valley known as the Fundy Basin that was created when the supercontinent Pangaea began to break up about 225 million years ago. As the continental plates moved apart, they ruptured, and blocks subsided along fault lines forming the rift valleys that became sedimentary basins. The Fundy Basin is the largest of these basins in Eastern North America. During the Triassic geological period between 208 and 220 million years ago, rivers swollen by intense rains carried coarse sediments (now sedimentary rocks) from nearby highlands into the Fundy Basin. Other deposits came from wind-blown sand dunes. Later, large lakes formed on the central part of the basin depositing finer sediments up to 1,000 metres thick and, as they dried up periodically, they left behind salt and gypsum deposits.

The red sedimentary sandstone base of Partridge Island dates from the late Triassic period. The covering layer of dark basalt was formed from magma and lava eruptions in the Jurassic period between 175 and 208 million years ago as continental drifting further weakened the Earth's crust.[18][19][20] Sandstones and siltstones were deposited on top of the basalt during cycles of drought and rain.[18] Although sandstone is soft and easily eroded, it forms high, steep cliffs where it is covered by basalt.[21] The basalt cliffs of Partridge Island contain small cavities formed when gases escaped as the lava cooled. Water seeping through these cavities or vesicles deposited minerals including gemstones such as amethyst, agate, jasper and calcite. Zeolite minerals such as chabazite and stilbite can also be found at Partridge Island.[7][19][22]

Fossils and dinosaurs

Since 1970 when the American paleontologist Paul E. Olsen discovered a neck vertebra of a long-necked dinosaur known as a prosauropod near Parrsboro, the north shore of the Minas Basin has been recognized as an important source of fossils.[18] In 1984, for example, amateur rock specialist Eldon George discovered the world's smallest dinosaur footprints at Wasson Bluff about 10 kilometres from Partridge Island.[18][23] Then, in 1986, Olsen and two colleagues announced they had retrieved 100,000 fossilized bones including some belonging to the oldest dinosaurs ever found in Canada.[18]

The cliffs at Partridge Island have not yielded such spectacular fossil finds, but Sarah Fowell, one of Olsen's students, gathered evidence in rocks at the island concerning a mass extinction of ancient animals about 200 million years ago at the boundary between the Triassic and Jurassic periods. She found what has been described as "a rapid and dramatic changeover" from the wide diversity of Triassic plant life to the much-lower diversity characteristic of the early Jurassic. Olsen said at the time that her findings were consistent with the theory that a giant asteroid collided with the Earth causing the mass extinction which allowed the dinosaurs to flourish unopposed. (Some scientists believe it was also an asteroid collision that wiped out the dinosaurs themselves about 135 million years later.)[18] More recently, however, scientists have theorized that massive volcanic eruptions may have led to the extinctions.[24][25]

Hiking trail

The three kilometre (1.9 mile) round-trip, hiking trail on Partridge Island climbs quickly to a height of about 61 metres (200 feet) above sea level, but there are four benches to rest on.[26] There is a lookoff at the top of the trail from which a viewing platform offers vistas of more than 60 kilometres (37 miles) of the coastline of the Upper Minas Basin.[20] Prominent features include Cape Blomidon, Cape Split, Cape Sharp, Cape d'Or, and Cobequid Bay. At dusk many lighthouses can be seen on the coasts surrounding Partridge Island. Visitors are advised to stay on the trail and to keep away from the edge of the cliffs, which could give way without warning.[5]

Wildlife

Partridge island has many types of wildlife; both birds and mammals. Mammals that can be viewed include deer, weasels, skunks, porcupines, squirrels, and mice. Many species of birds also inhabit this former island. Owls, blue jays, hawks, eagles and partridges can also be seen at Partridge Island. Various other birds of song also spend time here.

Tidal statistics

An interpretative panel at the lookoff on the Partridge Island hiking trail gives figures on tidal flows through the "Minas Gut", the section of the basin from Cape Blomidon to Cape Split and across to Partridge Island. "On each run of tide through this channel," it says, "flows 100 billion tons of water." The panel adds that more water passes through this channel each day than "the combined discharge of all the world's fresh water rivers." Harnessing this tidal energy, it says, could generate enough electricity to equal "250 medium sized nuclear power plants."[5] During each tide, more than eight cubic kilometres of water are forced through a channel that is barely five kilometres (3.1 miles) wide, raising and lowering the water levels inside the Minas Basin by 12 to 15 metres (39 to 49 feet). Tidal currents in the channel have been calculated to reach speeds of nearly 20 kilometres per hour (12.4 miles per hour).[7]

Bay of Fundy tides are the highest in the world and the highest of all occur in the Minas Basin. Several factors affect the Fundy tides including water depth and the shape of the coastline. Both contribute to a natural Fundy tidal oscillation, or flow of water back and forth, of about half a day, almost matching the half-day tidal cycle of the outside North Atlantic. This matching tidal cycle amplifies Fundy's tidal range as water flows in and out of the Bay across the threshold of the Gulf of Maine.[7][19]

Two tales

The narrowness of the Minas Basin in the vicinity of Partridge Island and the Basin's remarkable tides figure in two tales from the area. The first is a love story from the early 19th century and the second takes place when horsepower supplied the main mode of transportation in the era before automobiles and the internal combustion engine.

Love and Leander

Twenty-five-year-old Ebenezer Bishop from Greenwich in Kings County had fallen madly in love with Anne Lewis who lived with her family on a farm across the Minas Basin in Halfway River about 17 kilometres (10 miles) north of Partridge Island. During the winter of 1809, Ebenezer decided he would ask the 18-year-old Anne to marry him, but the Partridge Island ferry was not running because of thick ice in the Minas Channel. He enlisted the help of his friend, Nathaniel Loomer of Scot's Bay, who made a notched board or pole for Ebenezer to use as he crossed the ice floes. Ebenezer set out at daybreak during the brief period when the tide was slack, neither moving in nor out, and the ice pack was at rest. He decided to head for Cape Sharp, west of Partridge Island, but halfway across, the ice began to sink under him. He lay flat, and using the board as a bridge, managed to haul himself safely to another floe eventually reaching the cliffs at Cape Sharp. By dusk he had arrived at the farm where Anne was making supper. She readily agreed to marry him. Ebenezer rode back to Greenwich on a horse he borrowed from Anne's father returning to marry his sweetheart on November 1, 1809. The two sailed across the Basin to their new home where they lived together for many years. Anne and Ebenezer had seven children, naming one son John Leander, after the young man in Greek myth who swam the Hellespont to make love to the priestess, Hero. John Leander Bishop became a doctor and later served as a surgeon during the American Civil War.[4][27] Watson Kirkconnell memorialized Ebenezer's feat and son Leander's character in his poem "The Nova Scotian Hellespont":

The lad waxed mighty with the years; he grew at last to be

Acadia's first graduate, in Eighteen-forty-three.

A surgeon he became in time, and served with hand and brain

Throughout the bloody Civil War and all its wild campaign.

When questioned how he kept so cool, one answer would suffice:

He'd say he got it from his dad, who braved the Minas ice.[28]

The amazing "sea horse"

The second tale, related by the travel writer Will R. Bird, occurs at a time when men from the north shore of the Minas Basin used to cross the water to buy horses from farmers in the Annapolis Valley. During his summer travels in the late 1950s, Bird encountered an oldtimer on a farm near the Parrsboro golf course across the harbour from Partridge Island. "You ever hear of our sea horse?" the oldtimer asked. "There ain't nothing to match it in Nova Scotia." The story begins when Tom Smith crosses over to buy a mare from a man in Canning. The mare then had a black foal that "was one of the finest ever seen on this shore." After about seven years, the farmer from Canning showed up at Smith's farm and, obviously regretting that he had sold the mare, he offered Smith "more'n twice the going price" for his fast, black horse. "Tom was a man who watched the dollars and he just couldn't resist," the oldtimer said. The farmer from Canning took the boat back while Smith drove the horse around the Basin to deliver it. "He was no more'n back home," the old man said, "when he happened to look toward the pasture and there was the black horse. Tom couldn't believe his eyes." When he went down to the beach, he saw hoof marks showing where the animal had come ashore. Apparently, the horse had known to wait for low tide before attempting the crossing, but, it "made a mighty long swim just the same." The story ends with Smith returning to Canning to give the money back. "He told the man he couldn't sell a horse that wanted to be with him that much, and the stranger agreed."[29]

References

- ↑ "History - Town of Parrsboro, Nova Scotia". Town of Parrsboro. Archived from the original on 21 December 2007. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ↑ "World's Highest Tides". Town of Parrsboro. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ↑ "History - Town of Parrsboro, Nova Scotia". Archived from the original on 2007-12-21. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- 1 2 3 4 Brown, Roger David. (2002) Historic Cumberland County South: Land of Promise. Halifax: Nimbus Publishing Limited.

- 1 2 3 4 Interpretive panels at the lookoff from the Partridge Island hiking trail.

- 1 2 "The Ottawa House By-the-Sea Museum". Parrsborough Shore Historical Society. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Roland, Albert E. (1982) Geological Background and Physiography of Nova Scotia. Halifax: The Nova Scotian Institute of Science.

- ↑ "Fossil sites: Protecting the Past". Virtual Museum Canada. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ Hamilton, William B. (1996) Place Names of Atlantic Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, p.377.

- ↑ The Confederacy of Mainland Mi'kmaq. "The Story Begins" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ↑ Nova Scotia Archeology Society. "Tracing Lithic Sources in the Mi'kmaq Legends of Kluskap". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ↑ Spicer, Stanley T. (1991) Glooscap Legends. Hantsport, Nova Scotia: Lancelot Press, pp.15-16.

- ↑ Hornborg, Anne-Christine. (2008) Mi'kmaq Landscapes: From Animism to Sacred Ecology. Hampshire, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited, p.86.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lank, Evie; Byers, Conrad et al (2001) Heritage Homes and History of Parrsboro (2nd Edition) Parrsboro: Centennial Book Committee, pp.8-19.

- ↑ "Names and Places of Nova Scotia". Nova Scotia Archives. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ Champlain's Fundy voyages are outlined in Samuel de Champlain: Father of New France by Samuel Eliot Morison, (1972) Boston: Little Brown and Company, pp.35, 37, 97.

- ↑ Clarke, Ernest. (1995) The Siege of Fort Cumberland, 1776. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Thurston, Harry. (1994) Dawning of the Dinosaurs: The Story of Canada's Oldest Dinosaurs. Halifax: Nimbus Publishing Limited and The Nova Scotia Museum.

- 1 2 3 Atlantic Geoscience Society (2001) The Last Billion Years: A Geological History of the Maritime Provinces of Canada. Halifax: Nimbus Publishing Ltd.

- 1 2 Interpretive panel posted at the entrance to the hiking trail.

- ↑ "The Natural History of Nova Scotia: Basalt Headlands". Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ Pe-Piper, Georgia & Miller, Lisa. "Zeolite minerals from the North Shore of the Minas Basin, Nova Scotia". Atlantic Geology. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ↑ "Fossils of Nova Scotia". Nova Scotia Museum. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ↑ "Dark days of the Triassic: Lost world". Nature. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ↑ "The shifting face of a 200-million-year-old mystery". BBC News. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ↑ "Partridge Island Trail". Archived from the original on 2011-10-02. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- ↑ "Community Trees, John Leander Bishop, 1820-1868". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ↑ Kirkconnell, Watson (1976) The Flavour of Nova Scotia. Windsor, N.S.: Lancelot Press Limited, pp.38-40.

- ↑ Bird, Will R. (1959) These are the Maritimes. Toronto: The Ryerson Press, p.33.