| Pasukan Jihad | |

|---|---|

| |

| Also known as | Pasukan Putih |

| Founding leader | Abu Bakar Wahid |

| Leaders | Abu Bakar Wahid

Muhammad Selang Muhammad Albar |

| Dates of operation | 27 December 1999 - June 2000 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Group(s) | Tidore, Ternate, Makian |

| Motives | Return displaced Makian Muslims to Malifut |

| Headquarters | Muhajirin mosque, Ternate Island |

| Ideology | Islamism, Salafi Jihadism |

| Slogan | Hidup mulia atau mati syahid (Live honourably or die a martyr) |

| Status | Dissolved |

| Size | 18,000 |

| Means of revenue | Charity |

| Allies | Jemaah Islamiya |

| Opponents |

|

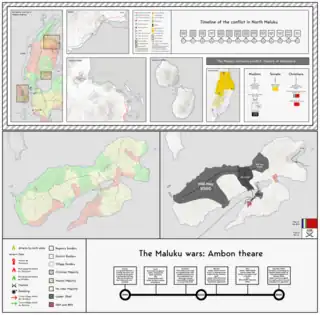

| Battles and wars | Battle of Ternate, Battle of Galela (Maluku sectarian conflict) |

| Colours | White, Green |

| Symbol seen in headbands |  |

| flag of sabale village branch |  |

Pasukan Putih ("White troops"),[1] later Pasukan Jihad ("Jihad troops"),[1] were a Muslim militia formed in North Maluku province, Indonesia. It was founded by Abu Bakar Wahid in December 1999, it gained regional prominence in early 2000 due to the Battle of Galela.[2]

Background

North Maluku and Ternate

The formation of North Maluku province in 1999 was a major political event that involved many local elites and communities. However, soon after the province was inaugurated, a fierce competition for the governorship emerged among four candidates: Mudaffar Syah, the Sultan of Ternate; Bahar Andili, the District Head of Central Halmahera; Syamsir Andili, the Mayor of Ternate City; and Thaib Armain, the Regional Secretary of the provincial bureaucracy. The first provincial parliament, which was dominated by the ruling Golkar Party, was supposed to elect the governor in 2000 based on the results of the 1999 district elections. The two frontrunners, Bahar Andili and Mudaffar Syah, had different visions for the province: the former wanted to emphasize its administrative and economic development, while the latter wanted to highlight its historical and cultural identity as the land of the sultanates (Maloko Kie Raha) and seek a special status within Indonesia. These political rivalries soon overshadowed the initial unity and solidarity that had characterized the secession movement from Maluku province, eventually Sultan Muadaffar Syah won the election as the Golkar candidate, by commanding his traditional authority among the local population.[3]

Expulsion of the Christians

The conflict in Malifut, especially the attack by the Kaos in October, increased the distrust and hostility between different ethnic and political groups in Ternate. Many Makians (a lot of whom were internally displaced to Ternate) and some Tidores accused Mudaffar Syah, the Sultan of Ternate, of instigating the Kaos to oppose the establishment of Malifut Sub-District and to launch a violent assault on the area. They claimed that the Sultan wanted to secure the support of the Kaos and other Christian communities on Halmahera, who had historical ties with the sultanate, for his governorship campaign. This suspicion was common among Makians, but also existed among some Tidores and other southern groups in Ternate City and on Tidore Island.[2][4]

The Sultan of Ternate, Mudaffar Syah, also angered many Makians in Ternate by refusing to evacuate the Malifut community to Ternate after the attack by the Kaos. He wanted the Makians to stay on Halmahera until a peaceful solution could be found. The Mayor of Ternate, Syamsir Andili, disagreed with him and sent trucks to transport the Makians from Malifut to Sidangoli, where they could take boats to Ternate. Andili cited the urgent humanitarian situation and the risk for Makians on Halmahera. This made Thaib Armain, Bahar Andili and Syamsir Andili, and their followers, join forces against Mudaffar Syah. The arrival of Makian IDPs from Malifut in October increased the tension between Ternates and Mudaffar Syah's supporters and the other southern groups in Ternate City. After some violent incidents occurred, Mudaffar Syah deployed his traditional troops, the Pasukan Kuning, to patrol the city and protect some Christian property and infrastructure. When anti-Christian riots erupted in Ternate on 6 November, the Pasukan Kuning rescued many Christians and brought them to the sultan's palace and nearby areas, such as Dufa Dufa.[2][5]

The Sultan of Ternate, Mudaffar Syah, provoked many Muslims, especially Makians and their allies, by protecting Christians during and after the November riots. He deployed his traditional troops, the Pasukan Kuning, to patrol the city and rescue Christians from the violence. Many Muslims accused him of being a Christian sympathizer and supporting the Kaos in the Malifut conflict. They also resented the presence and behavior of the Pasukan Kuning, who set up checkpoints and bases around the city and harassed and attacked migrants, especially Makians and Tidores. Some sources claimed that the Pasukan Kuning had a list of 100 Makians to kidnap and torture. The Pasukan Kuning also controlled the political center of the city, where most government offices and infrastructure were located. Most government activities were suspended over this period. Despite this situation, Mudaffar Syah still had a strong chance of becoming the governor of North Maluku, as he had the majority of the provincial parliament on his side. He was also respected by some Tidores and other Muslims for his Islamic and cultural traditions and his opposition to authoritarianism and corruption. He had shown his defiance against the former district head, Abdullah Assagaf, in 1998 by attacking his offices with the Pasukan Kuning.[1]

Invasion of Ternate

The rioting in Ternate started in late December, around the same time as the violence in Tobelo City. It began with a small incident on Monday 27 December at night, when the Pasukan Kuning guarding the Golkar Party building beat up a car driver who had hit their roadblock. The driver ran away to his home in Kampung Pisang. Later that night, he came back with a large group of youths from Kampung Pisang and Tanah Tinggi, and attacked the Pasukan Kuning near the Ternate Municipality offices. They threw stones and spears at each other until a police unit (Brimob) tried to stop them. But when the unit commander was hurt by an explosion, the police left and the fighting continued.[6]

During the fighting, the Kampung Pisang youths set fire to the ‘Maria Bintang Laut’ Catholic school, where dozens of the Pasukan Kuning were staying. The school was one of the few Catholic buildings that had survived the November riot. After that, both sides withdrew, the Pasukan Kuning to the Golkar Party building, their main base in the city center, and the growing numbers of Pasukan Putih to an area near the governor's office on Ahmad Yani Street.[6]

The next day, 28 December, at 5 a.m., hundreds of the Pasukan Kuning gathered with petrol cans and attacked Kampung Pisang, where the youths who had fought them lived. They burned down houses in Kampung Pisang and Maliaro, killing two people and forcing the residents to flee.33 Then they moved south to Tanah Tinggi and Takoma. A large number of Pasukan Putih assembled near the sports stadium and called for more people to join them. Kampung Pisang had many migrants from Tidore, whose houses were burned by the Pasukan Kuning. This news reached Tidore and angered their relatives there. Abu Bakar Wahid told hundreds of young men that the Sultan of Ternate was burning Tidores’ houses and had taken over Ternate. Many men from Tidore came to Ternate by boat to help the Makians and Tidores fight the Pasukan Kuning. They used spears, bows and arrows, homemade firearms and bombs to push the Pasukan Kuning back north. The Pasukan Kuning were outnumbered by the Pasukan Putih, who had thousands of men from Tidore. They could not hold their positions in the city center. By late afternoon, the Pasukan Putih had driven them back to the sultan's palace in the north-east of the city. The sultan arranged for the remaining Christians in Ternate to be evacuated by ship from Dufa Dufa to Halmahera. The Pasukan Putih destroyed the Golkar building, which was the base of the Pasukan Kuning. They said that Golkar should have been neutral, but it seemed to support the sultan in the conflict. They also destroyed a small building near the palace that was the headquarters of the Pasukan Kuning's youth wing. Many of them wanted to burn down the palace too, but Haji Kotu stopped them and said that the palace was a cultural treasure of North Maluku.[2][6]

The same day, 28 December, the interim governor of North Maluku, Surasmin, asked the Sultan of Tidore to stop the Tidores from fighting.The Sultan of Tidore and his delegation, including hundreds of traditional guards, came to Ternate that afternoon. He ordered to protect the new governor's office, saying that it was important for the whole North Maluku community. He also went to the Sultan of Ternate's palace, where the fighting stopped at 5 p.m. The leaders of the Pasukan Kuning and the Pasukan Putih met in front of the palace and made peace. The Pasukan Kuning took off their yellow hats as a sign of surrender. The Sultan of Tidore and the Pasukan Putih entered the palace and made the Sultan of Ternate sign a document taking responsibility for the conflict and promising to rebuild the houses that were burned. After that, the Pasukan Kuning and the Pasukan Putih went back to their homes. Mudaffar Syah left Ternate for Jakarta soon after. He said he was not forced to leave, but just went on a business trip. But many people said that he had to give up his authority in Ternate and North Maluku. The conflict killed between 18 and 200 people. Many more were injured. It also destroyed 241 houses, mostly in Kampung Pisang and near the palace. There were no military or police personnel during the fighting. In January, the provincial parliament removed Mudaffar Syah as parliamentary chairman. Some of his supporters had fled or changed their minds or been threatened. He was blamed for causing the violence and using it for his political goals. A North Malukan sociologist and a human rights commission called for an investigation of his role in the violence, but he was never charged with anything.[6]

Battle of Galela

After the takeover of Ternate, the Pasukan Jihad established mobilization centres at Muhajrin mosque and Toboko mosque in Ternate, and one in Tidore, the village of Tomalou, where Abu Bakar Wahid, the leader of the militia, lived. The militia grew to 18,000 members, including IDPs and former Pasukan Kuning members. It planned to attack Christian villages on Halmahera by speedboats.[7]

On 8 January 2000, the PJ left Tomalou for Sidangoli, where they clashed with the Christian Kaos, who had taken Malifut a few months prior. The Kaos had heard about the PJ's departure and had gathered at Dum Dum village. The PJ won the initial battles and prepared to attack Malifut, but were stopped from advancing by the police and army[7]

From January to March 2000, the PJ fought several battles with the Christians in Malifut and Galela. They attacked Jailolo, Makete, Soatobaru and Mamua, but were repelled by the Christian reinforcements. They also received reinforcements from Ternate and Tidore, increasing their number in halmahera to 5,000.[7]

On 29 May 2000, the PJ launched a failed attack on Duma. On 19 June 2000, they attacked again and succeeded in taking over the village. On 26 June 2000, an emergency was declared in North Maluku and the PJ was dissolved.[7]

References

- 1 2 3 Wilson, Chris (2008). Ethno-Religious Violence in Indonesia: From soil to God. Routeledge Contemporary Southeast Asia Series. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-415-45380-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Duncan, Christopher R. (2005). "The Other Maluku: Chronologies of Conflict in North Maluku". Indonesia (80): 53–80. ISSN 0019-7289. JSTOR 3351319.

- ↑ Wilson, Chris (2008). Ethno-religious violence in Indonesia: from soil to God. Routledge contemporary Southeast Asia series (1. publ ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 131–135. ISBN 978-0-415-45380-6.

- ↑ Wilson, Chris (2008). Ethno-religious violence in Indonesia: from soil to God. Routledge contemporary Southeast Asia series (1. publ ed.). London: Routledge. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-415-45380-6.

- ↑ Wilson, Chris (2008). Ethno-religious violence in Indonesia: from soil to God. Routledge contemporary Southeast Asia series (1. publ ed.). London: Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-415-45380-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Wilson, Chris (2008). Ethno-religious violence in Indonesia: from soil to God. Routledge contemporary Southeast Asia series (1. publ ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 137–139. ISBN 978-0-415-45380-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Wilson, Chris (2008). "Chapter 7: Killing in the name of God". Ethno-religious violence in Indonesia: from soil to God. Routledge contemporary Southeast Asia series (1. publ ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-45380-6.