Paul Hoste (1652–1700) was a Jesuit priest and naval tactician who produced the first major work on naval tactics.

Born at Brest in 1652, he was trained by the Jesuits and became Professor of Mathematics at the Royal Seminary at Toulon where he died in 1700, aged 48. He spent twelve years at sea with Victor Marie, duc d'Estrées, Montemart, Duc de Vienne and Anne Hilarion de Tourville during which time he analysed the practical limitations of ship handling and sought to create a system of sailing. Brian Tunstall[1] considers him the greatest of all the French tactical theorists.

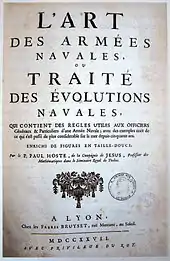

L'Art des Armées Navales ou Traité des Évolutions Navales

L'Art des Armées Navales ou Traité des Évolutions Navales ("Art of naval armies or treaty of naval evolutions") was published in Lyon in 1697, dedicated to King Louis XIV who rewarded Hoste generously. It enjoyed immediate success and was republished in 1727.

Hoste claims to have described all major sea battles from the time when galleys were supersede by broadside ships of the line. However, the list is not necessarily complete according to Jenkins,[2] who shows that although galleys were not strong enough to stand in the line of battle, they did form a part of battle fleets where they were used to tow damaged battleships out of the line. They remained in use in the calmer Mediterranean until at least 1700.

In the preface to the first edition, Hoste declared that without evolutions, fleets were like barbarians who waged war without knowledge, without order, everything depending on caprice and chance.[3] Evolutions provide a framework without which tactical opportunities cannot be seized. The book therefore claimed to show generals and other officers not only what was necessary, but also what was possible.

Orders of sailing

Hoste's system of sailing and battle formation was based on five ordres de marche which gave instructions on how to form a line of battle:

- 1st Order: a close-hauled line of bearing on either tack. A straight line could be drawn through their centres in a windward direction. This was the most difficult formation to understand and execute because of differences in size and capability of the vessels in the fleet.

- 2nd Order: perpendicular to the wind. A straight line drawn through the centre of the ships would be at right angles to the direction of the wind.

- 3rd Order: the fleet would form in a V-shape with the internal angle at 135 degrees, exactly bisected by the direction of the wind. This was a flexible formation which meant when close-hauled the leading division of ships would already be in line ahead.

- 4th Order: the fleet would divide into three double columns with the centre column slightly ahead. This was the most flexible formation and allowed the fleet to react to any course before the wind.

- 5th Order: the fleet would divide into three parallel lines, close hauled with the Admiral's column in the centre.

To clarify terminology, 'before the wind' means the ship is sailing in the same direction as the wind; 'close hauled' means the ship is sailing into the wind at an angle.

Hoste detailed the navigational methods required to allow each ship in the fleet to reach these formations effectively.

He also summarised the advantages of fighting from either windward or leeward positions. The Windward position allowed a fleet to control the battle, blew smoke from their guns onto the enemy fleet and allowed them to use fireships against the enemy. However it has the disadvantage that in heavy seas it may not be able to open its lower gun ports without risking flooding. The Leeward position allowed ships to easily drop out of the line when damaged and allowed ships full use of their gun decks. See also Naval tactics in the Age of Sail.

Advanced tactics

Hoste also analysed where and how to double the enemy line and demonstrated five methods to avoid being doubled.[4] This section of the book focuses strongly on defense rather than attack which reflects the strategic position of the French Navy in the late 1690s.

Naval signalling was briefly considered and he suggested a simple system of thirty-six signal flags of three colours. Particular types of signals were restricted to certain positions or groups of ships. British signalling at the time was very confusing and lacked standardisation.

Influence

Hoste's rigorous mathematical treatment of naval tactics dominated French naval strategy throughout the 18th century. It was only when the French Revolution removed experienced officers and sailors from the French navy, destroying its fighting ability, that British ships were able to take tactical risks and gained decisive victories.

References

- ↑ Naval Warfare in the Age of Sail, 1990, p59, ISBN 0-7858-1426-4

- ↑ Jenkins, History of the French Navy, 1973, p21-68, ISBN 0-356-04196-4

- ↑ Quoted in Tunstall, Naval Warfare in the Age of Sail, 1990, p59, ISBN 0-7858-1426-4

- ↑ Quoted with illustrations in Tunstall, Naval Warfare in the Age of Sail, 1990, pp 62–63, ISBN 0-7858-1426-4

External links

Media related to Paul Hoste at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Paul Hoste at Wikimedia Commons