Paul Soleillet | |

|---|---|

Paul Soleillet by Mathieu-Deroche, c. 1886 | |

| Born | Jean-Joseph-Marie-Michel-Paul Soleillet 29 April 1842 Nîmes, France |

| Died | 10 September 1886 (aged 44) Aden, Yemen |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Explorer |

Paul Soleillet (29 April 1842 – 10 September 1886) was a French explorer in West Africa and Ethiopia. He was a strong believer in opening up Africa to trade through peaceful means, and thus bringing the benefits of French civilization to the natives while gaining commercial profits for France.

Although Soleillet had no scientific training and did not speak the local languages, he was willing to travel on foot with little baggage and few companions, and thus generally avoided being robbed. After a short private expedition into the interior of Algeria he managed to raise support for a more ambitious expedition to In-Salah in 1874 to open a commercial center in the central Sahara. The expedition was a flop, since the coastal merchants had little to offer the interior tribes, who had little to offer in return. Despite this, Soleillet found himself the spokesman for groups interested in a Trans-Saharan railway, and was subsidized to make an expedition from Senegal into the Western Sudan in 1878. This achieved little, but he was treated as a hero on his return. He made an unsuccessful attempt to travel from Senegal to Algeria in 1880. Two French expeditions into the Sahara in 1881 were disastrous, and Soleillet's reputation collapsed. He spent his last years in East Africa tying to develop trade between the French enclave of Djibouti and Ethiopia. Just before he died he was in partnership with Arthur Rimbaud[lower-alpha 1] in an attempt to ship arms to the future Emperor of Ethiopia.

Early years (1842–71)

Jean-Joseph-Marie-Michel-Paul Soleillet was born in Nîmes on 29 April 1842.[2] His family originated in Marseille but was long settled in Nîmes. His father retired as Director of Direct Contributions in Montpellier. His mother, a Boyer, came from a family with a mid-sized shop that sold furniture and jewelry. His cousin, Ferdinand Boyer, was a barrister in Nîmes who became a deputy in 1871. He was also related to the Chabaud-Latours, a prominent local family with national connections.[3] Soleillet attended secondary school at Avignon.[2] He was a day student at the college of Saint-Joseph.[4]

His father gave him a job in his office, and was grooming him to succeed him. He had been pushed into marrying a girl from a good family. When she died in childbirth he fell into a depressed state and wanted to escape to a new environment. He became partner of a small manufacturer of gold and silver lamé fabrics designed for the North African market, travelled to Algeria and fell in love with the country.[3] He first visited Algeria in 1865 and returned to Algiers in 1866, when he visited much of French Algeria. In 1867 he was in the regency of Tunisia, where a cholera epidemic broke out.[5] He helped care for the sick.[2] His company went bankrupt, and then in 1870 the Franco-Prussian War began.[3] He returned to France and enrolled as a private soldier. He served in the Battle of Coulmiers and throughout the Loire campaign.[2]

In October 1871 Soleillet wrote to the Minister of Public Works about bringing trade from the Central Sahara and West Sudan to the Algerian markets.[6] The government in Paris saw no reason to interfere in a purely Algerian matter. Charles de Larcy, the Minister of Commerce, ignored Soleillet's letters.[7] However, in Marseille Soleillet was introduced to Félix de Surville, a financier and economist who put Soleillet in touch with the Société Générale Algérienne. After several meetings he was advised to return to Algeria where the director of the Comptoir d'Alger would be able to help him. His father died around this time.[6]

African explorations

Algeria (1872–74)

Soleillet returned to Algeria in 1872 and visited South Algeria as far as the Amour Range and M'zab.[3] This first expedition took from September 1872 to April 1873.[8] He wore Arab dress and travelled light with a small escort of four men.[2] However, he had no scientific training and did not understand any Arabic, so was poorly qualified to be an explorer.[3] He had borrowed 1,500 francs to finance the Algerian trip and was slow to return it.[8] He returned to Algiers after completing this first expedition.[9] There he gained the friendship of Auguste Warnier, the Deputy for Algeria, who introduced him to General Hippolyte Mircher (1820–78), another specialist in the Sahara.[7] He met generals Loverdo and Wimpffen, the geographer MacCarthy(fr) and the professor Masqueray.[10]

He returned to France to try to raise money from official and private sources to fund an expedition to the oasis of In-Salah in the Tuat, which he thought was a central point where all the routes converged that linked the Mediterranean basin with the Niger basin, but which was at that time more impenetrable than Timbuktu.[10] Soleillet proposed to create a great commercial center in the South of Algeria, with roads uniting Algeria to Niger. He suggested starting an annual fair in El Goléah, and proposed to open a commercial agency in In-Salah.[7] Although there was nothing new in his proposal, it caught the imagination of the Algerian press, who enthusiastically supported the plan.[7] The colonists in Algiers had long seen great promise in the trans-Saharan trade.[7]

Soleillet said later the goal of his trip from September 1872 to April 1873, and from 1873 to 1874, was to determine the needs and resources of the countries with which France would open commercial links and bring the benefits of French civilization. France would thus peacefully conquer the Sahara and Sudan.[8] The president of the Algiers Chamber of Commerce, M. Henry, backed Soleillet's plan. In August 1874 General Antoine Chanzy, governor general of Algeria, gave his support to the Henry-Soleillet project. The goal was to open a commercial agency in In-Salah, not to make a new conquest.[11] The Societé de Géographie de Lyon, an association of French companies trading in Africa, sponsored his expedition to In-Salah.[12] However, Soleillet had difficulty raising money and did not get support from traders in Oran and Constantine.[13]

In-Salah (1874)

Soleillet adopted Arab costume for his 1874 trip to In-Salah so he would be seen not as a conqueror but as a brother.[8] He thought that taking astronomical observations might make the natives suspicious, so just used a chronometer to estimate the duration of each stage of the journey and took the general direction of the route several times a day.[3] Soleillet was accompanied on his trip to In-Salah by four merchants who brought goods from Algiers such as sugar, matches, candles and shot pellets. The interior merchants had nothing of great interest to sell, apart from second-rate ostrich plumes and ivory, and poorly salted hides. Soleillet only spent a few hours at In-Salah, where the notables refused to meet him or read his messages, and made it clear their loyalty was to the Sultan of Morocco.[13] There is no evidence that Soleillet was greatly interested in personal gain.[8] He was always a Romantic, eager for adventure.[14] He wrote of his arrival in In-Salah in 1874, accompanied by four Muslims,

When we were at the top of the southern slope, a great emotion took hold of me, I stopped my méhari at the top of the dune and I began to contemplate the country that offered itself to my view. My heart began to beat in my breast strongly enough to split it, and my eyes were wet with tears, all that I saw, all that I contemplated, I was the first European to see, to contemplate. I felt then a feeling that it is easy to indicate, but that it would be impossible to define ...[14]

Of In-Salah he reported that "the trade in Negro slaves is undertaken on a large scale throughout the Sahara. In-Salah, like the other oases, receives and buys a large quantity of slaves."[15] Soleillet considered that the abolition of slavery would solve nothing, since the African tribes would continue to make war, and if they could not sell their captives would simply massacre them. He proposed that the solution was for France to buy the slaves and use them to repopulate the Sahara, where they would be introduced to agriculture and the arts and the civilization of Europe. They would be helped to build towns and villages and after a commitment of ten years, for example, would be granted their liberty, their homes, the lands they had cultivated and their work tools.[16] Based on his report on the In-Salah expedition the Avignon Chamber of Commerce argued that the French government should help the French trading monopolies by increasing their official presence in the Sahara and the Western Sudan.[12]

France and Senegal (1874–78)

On returning to France Soleillet became a key advocate of the proposed trans-Saharan railway. Although he was shy and a poor public speaker, he managed to stir his audiences to enthusiasm to the project.[13] In 1874 and 1875 he spoke in Avignon, Lyon, Montpellier and Paris. He was invited to Spain, Holland and Belgium, and spoke at the International Congress of Geography in 1875. He talked of "peaceful civilization" and of the great commercial opportunities for France.[17] It was thought by the French trading companies that the trade in Senegal and that in Algeria must be linked by a route through the Tukulor country of the Western Sudan.[12] Soleillet's next exploration was to travel from Algiers to Saint-Louis, Senegal, by way of In-Salah and Timbuktu. In December 1875 the proposed expedition was downsized to one to the interior from Senegal.[17]

Soleillet faced opposition from specialists in exploration projects. Henri Duveyrier constantly denounced the lack of science in Soleillet's reports. In 1876 Soleillet asked for financial support for an expedition to Timbuktu, but was turned down. The tide changed in 1877 when the Republicans took power, and an influential group gave their support to Soleillet's plans. In February 1877 General Chanzy encouraged the Missions Commission to give Soleillet the subsidy he had requested to go to Timbuktu in one of the annual native caravans.[18] In 1877 Ferdinand de Lesseps began defending the railway project. In December 1877 a new cabinet included several supporters of Saharan penetration including Jules Armand Dufaure, Léon Teisserenc de Bort, Charles de Freycinet and Georges Perin. In April 1878 Soleillet was granted a subsidy of 1,000 francs.[19]

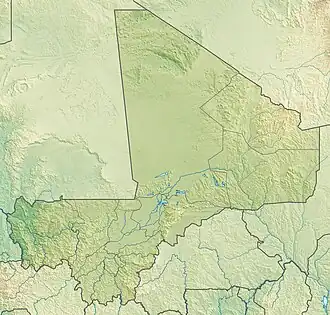

Saint-Louis to Ségou (1878–79)

In 1878 Governor Louis Brière de l'Isle of Senegal charged Soleillet with an official mission to Ségou in the Western Sudan funded by his administration, with the support of the merchants of Saint-Louis.[20] The purpose was to collect information about the economic potential of the Western Sudan and about how France could expand its influence in the region.[21]

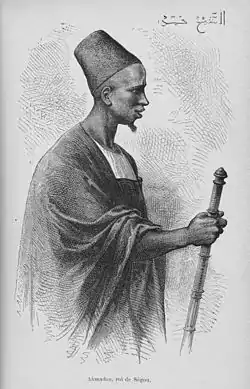

Ahmadou Sekou Tall, son of Umar Tall, had inherited his father's Toucouleur Empire in the Western Sudan on the upper Niger River and upper Senegal River. Umar's armies were mainly Futanke, Pulaar speakers from Futa Tooro on the middle Senegal River.[22] The French conceded Umar's authority over the upper Senegal and lands further east.[23] Ahmadou tried to consolidate an imperial state with its capital at Ségou on the Niger, and tried without success to get the Futanke to move to Ségou. He had defeated a rebellion by two of his half brothers in Kaarta in 1871.[22] By the late 1870s Ahmadou's half brother Muntaga was again showing signs of independence. The French wanted to arrange treaties with Ahmadou Sekou through which they could extend their influence into the interior. On his side, Ahmadou wanted the French to supply weapons and let him raise fighters in Futa Toro.[23]

Soleillet left Saint-Louis for Ségou on 28 April 1878 and travelled eastward through Kaarta and Bélédougou.[12] He took two African servants and less than a dozen donkeys with him. One of the servants, Yaguelli, was both his domestic servant and his interpreter.[24] Soleillet felt that his lack of pomp and peaceful disposition would almost always win him friendly treatment.[8] He visited the area when Muntaga's rebellion was starting to develop, and when the French were starting to push eastward. Soleillet passed through the western Umarian garrisons of Kooniakary and Dialla.[23] At Kooniakary Soleillet found several Futanke who could speak some French, and these were used to watch him and make sure he was told only the official line.[24] However, Soleillet heard of the rebellion from one of the dissident brothers, whom he met at Dialla, and from then on constantly tried to get information about any challenges to Amadu.[24]

Soleillet reached Ségou in October 1878.[12] In the capital he was always accompanied by Samba Njay, who had in the past lived in Saint-Louis.[24] In late December 1878 he saw a masquerade procession in a village just south of Ségou.[25] He wrote in his journal, "...and I stopped there....Why...to see Guignol! A square tent of white and blue striped fabric is installed in a boat with two paddlers, an ostrich head fixed upon a long neck extends from the front...then two marionettes appear suddenly out of the middle of the tent, one clothed in red, the other in blue, and they abandon themselves to some grotesque pantomimes. The drums, placed in a second boat, accompany the spectacle with deafening music.[26]" He went on the describe how the bird masquerade was brought to shore into a large clearing in the village, where the bird and many other masquerade characters were performed long into the night.[26]

The French annexation of Logo in September 1878 caused Soleillet's mission to be unsuccessful, and Ahmadou said he would not establish normal relations with the French while Brière de l'Isle remained governor of Senegal. Soleillet stayed at Ségou until 20 January 1879, then returned to Saint-Louis by way of Nioro, Kooniakary and Médine.[12] On his return to France Soleillet was received with pomp by the Geographical Society of Bordeaux.[20] He met Freycinet and Jules Ferry, and was given the palms of an officer of the Académie française.[19] He received an inscribed gold chronometer from the Société de géographie de Lyon.[17] Perin gave a short report of Soleillet's expedition to Ségou, and said this proved the administration had been right to support him.[19]

Development plans (1879)

In his reports Soleillet advocated what was to become the Dakar–Niger Railway linking Senegal to the middle Niger at Ségou.[27] In July 1879 the French Chamber of Deputies discussed the credits needed for the trans-Saharan railway.[19] In July 1879 the government charged Colonel Paul Flatters with exploring a route to Sokoto, between Niger and Chad.[20] Soleillet was consulted on these plans, and on the plans for Senegal.[20]

On 1 August 1879 Soleillet read a paper to the Geographical Society of Paris on his journey to Segou-Sikoro.[28] He said that a railway could easily be constructed from the Senegal to the Niger since the land was level, fertile and inhabited only by two races, the Bambara and the Solenké [Soninke?]. If a preliminary trade road were built from the Senegal to the Niger the country it crossed would provide many trade products including a type of vegetable wax that could be reduced to oil and made to serve many useful purposes.[28] A further recommendation was to open the Senegal to navigation up to Bafoulabé, and from there to build a canal to the Niger at Bamakou. The project would bring an estimated 37 million semi-civilized people into close connection with Senegal. The total cost was estimated at $5,000,000. The High Commission had adopted the project and would start surveying the canal route at once.[29] In December 1879 the deputies voted a grant for construction of the railway to Senegal.[19]

Saint-Louis to Adrar (1879–80)

In April 1879 the Administrative Council of Senegal said that his visit to Ségou had been successful, granted him 20,000 francs in subsidies, and announced that he was in charge of a new mission. The next January he was to travel by Tchad (Tichit?) and Oualata to Timbuktu, and from there return to Europe by the most convenient route.[20] In August 1879 it was reported that Soleillet, who had been granted £800 by the Senegal government to return to France for health reasons, was to return and try again in December 1879 to pass via Ségou and Timbuktu into Algeria. If turned back, he proposed to make repeated attempts until he succeeded. He was particularly interested in exploring the land between In-Salah and Timbuktu in connection with the projected Trans-Sahara railway.[30]

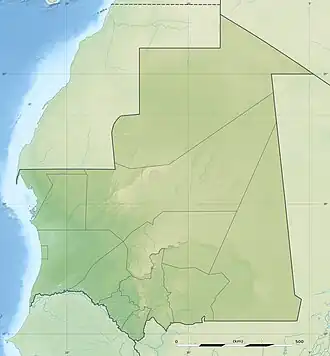

While Soleillet's first three expeditions had been financed by French commercial interests, his fourth was subsidized by the French Ministry of Public Works.[12] Soleillet's fourth expedition took him from Saint-Louis to Adrar.[31] This was his second attempt to travel from Senegal to Algeria.[32] On 15 March 1880 Soleillet met Sheikh Saadbouh at his encampment in Inchiri, in what is now northeastern Mautitania. He gave various gifts to the Sheikh, who gave him milk, dates and mutton in return. Further north in the Akhmeyou plain in Adrar, two days walk north of Atar, he was pillaged by a band of Moors of the Oulad Delim tribe armed with guns. The Sheikh sent his brother and nephew to rescue Soleillet and bring him back to his camp.[33] Soleillet was forced to retrace his steps to Saint-Louis, and return to France to obtain fresh resources.[32] In April 1880 ten notables of Saint-Louis again said they would help Soleillet in his efforts to open up the country to their business.[20]

Fall from grace (1881)

Soleillet lost support from the Senegal authorities when he sent a letter to the radical journal Le Rappel in which he criticized the Senegal military administration for inefficiency and waste, which might cause the planned railway to fail.[34] In February 1881 a column commanded by Captain Joseph Gallieni, exploring a future route from the Senegal to the Niger, was stopped by Ahmadou Sekou, stripped of its baggage and held captive before being released for ransom. In April 1881 news arrived that the second Flatters expedition had ended in disaster, with most of its members killed.[35] The day of lone explorers was clearly over.[34]

Marie François Sadi Carnot, Minister of Public Works, said he did not want to hear about any more Saharan expeditions.[34] The government said that anyone who visited the tribes of West Africa must have a solid understanding of the Arabic language and the Moslem religion. He must also present himself openly as a European and make it clear to the natives that he had the right to live among them and they would benefit from relations with France.[14] Soleillet's enemy Duveyrier wrote "Nothing in Mr. Soleillet's antecedents demonstrates his abilities as explorer in Africa."[34] On 1 December 1881 Brière de l'Isle ordered Soleillet expelled from the colony.[34]

East Africa (1882–85)

In 1881 Soleillet was given charge of a commercial mission to the Gulf of Tadjoura and the kingdom of Shewa.[36] Soleillet was recruited as general agent of the Société français d'Obock.[37] The port of Obock had been occupied by the French since 1856, but little had been done to develop it.[38] The commercial station at Obock was to receive the products of Shewa, including ivory, coffee, hides and the musk of civets for use in perfume.[39] In January 1882 Soleillet established a factory at Obock, Djibouti. In the middle of the year he received a caravan of hides sent by Menilek, the Negus of Shewa and future Ethiopian Emperor. This was enough to convince him that a great emporium could be established on the shores of the Gulf of Tadjoura to the south of Obock.[40] Soleillet built a tower at Obock that was blown down by the wind in 1885. A penitentiary was later built at this location.[41]

Soleillet set off to explore the routes of the caravans carrying salt and other goods in the Afar trade to find an alternative to the Issa Somali routes that terminated at Zeila.[40] In October 1882 Soleillet joined his associate Léon Chefneux at Shewa. Their company, which was to have supplied arms to Menilek, went bankrupt and Soleillet found he was a dependent rather than a partner of the king.[40] The king of Shewa gave him large tracts of land and granted him a concession to build a railway to the Gulf of Aden.[36]

Until Soleillet had arrived the Italian and French traders had tried to avoid disputes and display a common European front. By 1883 there were constant quarrels as Pietro Antonelli(It) tried to become the main adviser to Menilek in place of Soleillet.[42] Soleillet visited the Kingdom of Kaffa in 1884.[36] He described the trade of Bonga as primarily slaves, coffee, musk of civets, coriander and ivory, with a turnover of $200,000 and $300,000 a year.[43] He left Shewa in the middle of 1884.[40] In July–August 1884 Soleillet and Chefneux crossed the Sultanate of Aussa during their return journey from Shewa, with the sultan's permission, causing some alarm to Menilek.[44] Soleillet returned to Europe in 1884, soon afterwards returning to Shewa.[36] For his work in Ethiopia he was awarded the cross of the Legion of Honour.[45] In 1884 Obock was upgraded to a naval coaling station.[38]

Arms dealer (1885–86)

Towards the end of his life Soleillet became involved in arms trafficking in Ethiopia.[31] Arthur Rimbaud had been established at Harar in 1881 as the agent of an Aden-based company belonging to Alfred Bardey of Lyon.[37] In 1885 both Soleillet and Rimbaud started their own businesses as arms dealers. They teamed up in January 1886 for a major arms deal. The goods were old rifles that cost seven or eight francs each in Liège or France, but could be sold for about 40 francs to the king of Shewa. The costs and risks were high.[39] Rimbaud wrote that the people along the route were Dankalis, Bedouin grazers and Muslim fanatics. Although the caravan was armed and the Bedouins only had spears, all caravans were attacked.[46]

Rimbaud's partner Pierre Labatut received the merchandise in Aden while Rimbaud installed himself at Tadjoura to organize the caravan. Meanwhile, Soleillet, after a short stay in France where he promoted Menelik's cause, embarked at Marseille on 31 January 1886 for Obock. He wrote that he intended to go from there to Shewa to continue the work of rapprochement between Shewa and France. His expedition would be funded by his agreement to accompany the convoy of arms and ammunition from Obock to Shewa. The arms were landed at Tadjoura in February, but could not be moved inland because Léonce Lagarde, governor of the new French administration of Obock and its dependencies, issued an order on 12 April 1886 prohibiting the sale of weapons.[46]

Death and legacy (1886–1942)

In 1886 Soleillet published two versions of his voyages to Ankober and Kaffa. Obock, le Choa [Shewa], le Kaffa was anecdotal, aimed at the general reader. The more complete version included his travel journal and letters addressed to Gabriel Gravier(fr), honorary president of the Normandy Geographical Society, who published it after Soleillet's death as Voyages en Éthiopie.[47] On 10 September 1886 Paul Soleillet died of sunstroke in a street in Aden at the age of 44.[48][39] He and Rimbaud were still trying to move the shipment of muskets from Tadjoura.[40] Rimbaud found another partner, but continued to struggle and lost his investment. He suffered a leg injury which was poorly treated, and died in April 1891.[39] Léon Chefneux went on to develop the trade of Djibouti with Ethiopia.[40]

The geographer Élisée Reclus, who created the 19-volume Géographie universelle (1875–94), saw Soleillet as one of the best explorers of the 19th century. The historian Henri Brunschwig(fr) saw him as only an "imprudent exploiter of the geographical movement."[49] The sculptor Jean Barnabé Amy made a monument to Paul Soleillet (1888, Nîmes).[50] The bust was installed next to the Esplanade in Nîmes, opposite the Arena. After World War I (1914–18) a war memorial was erected in place of the bust, which was moved to the triangular grove of the Jardin de la Fontaine. During World War II (1939–45) on 5 February 1942 the bust was removed to be melted down.[51]

Publications

Publications by Paul Soleillet include:[48]

- Paul Soleillet (1872), Notes sur un projet pour l'établissement de docks à Laghouat (Algérie), p. 20

- Paul Soleillet (1874), Exploration du Sahara central : voyage de Paul Soleillet d'Alger à l'oasis d'In-Çalah (Rapport présenté à la Chambre de Commerce d'Alger), Alger, p. 144

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Paul Soleillet (1875), Voyage d'Alger à St-Louis-du-Sénégal par Tombouctou, Avignon: impr. de F. Seguin aîné, p. 33

- Paul Soleillet (1876), Cercle rouennais de la Ligue de l'enseignement.Chemin de fer d'Alger à St-Louis-du-Sénégal par Tombouctou, Rouen: impr. de L. Brière, p. 13

- Paul Soleillet (1876), Exploration du Sahara central : avenir de la France en Afrique, Paris: Challamel aîné, p. 106

- Paul Soleillet (1877), L'Afrique occidentale : Algérie, Mzab, Tildikelt, cartography by Gabriel Gravier, Avignon: imprimerie de F. Seguin aîné, p. 280

- Paul Soleillet (1877), Chambre de commerce de Lille. Chemins de fer projetés dans le Sahara, Lille: impr. de Danel / Chambre de commerce et d'industrie. Lille, pp. 187–197

- Paul Soleillet (1881), Jules Gros (ed.), Les voyages et découvertes de Paul Soleillet dans le Sahara et dans le Soudan en vue d'un projet d'un chemin de fer transsaharien, racontés par lui-même, preface by Émile Levasseur, Paris: M. Dreyfous, p. 240

- Paul Soleillet (1886), Obock, le Choa, le Kaffa, récit d'une exploration commerciale en Éthiopie, Paris: M. Dreyfous, p. 318

- Paul Soleillet (1886), "Voyages en Éthiopie (janvier 1882-octobre 1884)", Bulletin de la Société normande de géographie (Notes, lettres et documents divers), Rouen: impr. de E. Cagniard: 353

During the Ségou mission Soleillet wrote several letters and reports, and he kept a journal and notebook. Gabriel Gravier later pulled together this material into a published book.[21]

- Paul Soleillet (1887), Gabriel Gravier (ed.), Voyage à Ségou, 1878–1879, Paris: Challamel aîné, p. 513

- Yarnall, Ellis H., ed. (January 1880), "Geography and Travels", The American Naturalist, The University of Chicago Press for The American Society of Naturalists, 14 (1): 62–65, doi:10.1086/272484, JSTOR 2449403

Notes

- ↑ Rimbaud 2013, p. xxix.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ricquet 1895, pp. 28–31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Valette 1980, p. 254.

- ↑ Soleillet 1881, p. viii.

- ↑ Soleillet 1881, p. xii.

- 1 2 Soleillet 1881, p. xv.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Valette 1980, p. 257.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Valette 1980, p. 255.

- ↑ Soleillet 1881, p. xvi.

- 1 2 Soleillet 1881, p. xvii.

- ↑ Valette 1980, p. 258.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Imperato & Imperato 2008, p. 273.

- 1 2 3 Valette 1980, p. 259.

- 1 2 3 Valette 1980, p. 256.

- ↑ Brower 2009, p. 310.

- ↑ Dodille 2011, p. 34.

- 1 2 3 Valette 1980, p. 260.

- ↑ Valette 1980, p. 261.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Valette 1980, p. 262.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Valette 1980, p. 263.

- 1 2 Hanson 1996, p. 12.

- 1 2 Hanson 1991, p. 145.

- 1 2 3 Hanson 1991, p. 146.

- 1 2 3 4 Hanson 1991, p. 147.

- ↑ Vogel & Arnoldi 2001, p. 72.

- 1 2 Vogel & Arnoldi 2001, p. 75.

- ↑ Kanya-Forstner 1969, pp. 67–71.

- 1 2 Royal Geographical Society 1879, p. 686.

- ↑ Yarnall 1880, p. 65.

- ↑ Projected Journey of M. Soleillet ...1879, p. 512.

- 1 2 Imperato & Imperato 2008, p. 274.

- 1 2 Soleillet 1881, p. i.

- ↑ Cheikh Talibouya Niang, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Valette 1980, p. 264.

- ↑ Brower 2009, p. 241.

- 1 2 3 4 Royal Geographical Society 1886, p. 655.

- 1 2 Dubois 2003, p. 57.

- 1 2 Recent African Exploration 1885, p. 114.

- 1 2 3 4 Dubois 2003, p. 58.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Caulk 2002, p. 28.

- ↑ Morin 2004, p. 192.

- ↑ Caulk 2002, p. 31.

- ↑ Pankhurst 1968, p. 448.

- ↑ Morin 2004, p. 71.

- ↑ Recent African Exploration 1885, p. 115.

- 1 2 Dubois 2003, p. 59.

- ↑ Dubois 2003, p. 68.

- 1 2 Paul Soleillet (1842–1886) – BnF.

- ↑ Dubois 2003, p. 66.

- ↑ Genova 2006.

- ↑ NDLR.

Sources

- Brower, Benjamin Claude (2009-06-01), A Desert Named Peace: The Violence of France's Empire in the Algerian Sahara, 1844-1902, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-51937-3, retrieved 2017-12-09

- Caulk, Richard Alan (2002), "Between the Jaws of Hyenas": A Diplomatic History of Ethiopia (1876-1896), Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-04558-2, retrieved 2017-12-09

- Cheikh Talibouya Niang, Cheikhna Sheikh Saadbouh and Paul Soleillet, retrieved 2017-12-10

- Dodille, Norbert (2011), Introduction aux discours coloniaux (in French), Presses Paris Sorbonne, ISBN 978-2-84050-812-0, retrieved 2017-12-10

- Dubois, Colette (2003-02-01), L'or blanc de Djibouti. Salines et sauniers (XIXe-XXe siècles) (in French), KARTHALA Editions, ISBN 978-2-8111-3613-0, retrieved 2017-12-10

- Genova, André Alauzen Di (2006), "Jean-Barnabé Amy", Dictionnaire des peintres et sculpteurs de Provence, Alpes, Côte d'Azur (in French), Éditions J. Laffitte, retrieved 2017-10-27

- Hanson, John H. (1991), "African Testimony Reported in European Travel Literature: What Did Paul Soleillet and Camille Piétri Hear and Why Does No One Recount It Now?", History in Africa, Cambridge University Press, 18: 143–158, doi:10.2307/3172060, JSTOR 3172060, S2CID 161249958

- Hanson, John H. (1996), Migration, Jihad, and Muslim Authority in West Africa: The Futanke Colonies in Karta, Indiana University Press, ISBN 0-253-33088-2, retrieved 2017-12-09

- Imperato, Pascal James; Imperato, Gavin H. (2008-04-25), Historical Dictionary of Mali, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-6402-3, retrieved 2017-12-10

- Kanya-Forstner, A. S. (1969), The Conquest of the Western Sudan A Study in French Military Imperialism, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-07378-3

- Morin, Didier (2004), Dictionnaire historique afar: 1288-1982 (in French), KARTHALA Editions, ISBN 978-2-84586-492-4, retrieved 2017-12-10

- NDLR, Le buste de Soleillet (in French), retrieved 2017-12-08

- Pankhurst, Richard (1968), Economic History of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa: Haile Selassie I University

- Paul Soleillet (1842–1886) (in French), BnF: Bibliotheque nationale de France, retrieved 2017-12-08

- Patterson, R. R. (August 1879), "Projected Journey of M. Soleillet in West Africa", Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography, New Monthly Series, Wiley on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), 1 (8): 509–512, doi:10.2307/1800598, JSTOR 1800598

- Ricquet, V. (1895), "Paul Soleillet : L'explorateur nîmois (1842–1886)", Gard (in French), retrieved 2017-12-08

- "Recent African Exploration", Science, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 5 (105): 114–115, 6 February 1885, Bibcode:1885Sci.....5..114., doi:10.1126/science.ns-5.105.114, JSTOR 1759992, PMID 17748960

- Rimbaud, Arthur (2013-03-27), Rimbaud Complete, translated, edited and introduced by Wyatt Mason, Random House Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-307-82410-3, retrieved 2017-12-10

- Royal Geographical Society (October 1879), "Proceedings of Foreign Societies", Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography, Wiley on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), 1 (10): 686, JSTOR 1800567

- Royal Geographical Society (October 1886), "Obituary: Paul Soleillet", Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography, Wiley on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), 8 (10): 655, JSTOR 1800997

- Soleillet, Paul (1881), Les voyages et découvertes de Paul Soleillet dans le Sahara et dans le Soudan (in French), preface by E. Levasseur, edited by Jules Gros, M. Dreyfour & M. Dalsace, retrieved 2017-12-10

- Valette, Jacques (Fall–Winter 1980), "Pénétration française au Sahara et exploration : le cas de Paul Soleillet", Revue française d'histoire d'outre-mer (in French), 67 (248–249): 253–267, doi:10.3406/outre.1980.2261

- Vogel, Susan; Arnoldi, Mary Jo (Spring 2001), "Sòmonò Puppet Masquerades in Kirango, Mali", African Arts, UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies Center, 34 (1): 72–77, doi:10.2307/3337736, JSTOR 3337736