Penelope Powell | |

|---|---|

_cave_diver.png.webp) Penelope Powell, 1935 | |

| Born | Penelope Margaret Hopper 14 October 1904 Suffolk, England |

| Died | 1 October 1965 (aged 60) Isles of Scilly, England |

| Other names | 'Mossy' Penelope Tyndale-Powell |

| Known for | Cave diving |

| Spouses |

Reginald Oliver Tyndale-Powell

(m. 1927; div. 1934) John "Jock" Baxter Wyllie

(m. 1936) |

| Children | 5 |

Penelope Powell (b. Suffolk, 14 October 1904, d. Scilly Isles, 1 October 1965) was a pioneering cave diver. She was Diver No. 2 for the first successful cave dive using breathing equipment in Britain[1] at Wookey Hole Caves in the Mendip Hills, Somerset on 18 August 1935.[2][3]

Personal life

Born Penelope Margaret Hopper to Dr Leonard Bushby Hopper and Mabel Elizabeth Jackson in Kessingland, Suffolk, she was the eldest of three children. By 1911 the family was living in Cornwall. She was niece to Rev. C. F. Metcalfe, an early explorer of the Mendip caves.[4]

In 1927 she moved to Malaysia where she married Reginald Oliver Tyndale-Powell at St. George's Church, Penang.[5] They had two children.[6] She returned to the UK in 1934, where they divorced. She was living in Priddy, Somerset, and working at Wookey Hole Shop and Caves at the time of her cave dive the following year.[7] Subsequently, she worked at Gough's Cave in Cheddar Gorge.[8]

In 1936 Powell moved to Bristol and married John "Jock" Baxter Wyllie, a Clifton College housemaster. They had three children. In 1938 the couple set up Tankerton School, a preparatory school for boys and a mixed kindergarten, in Mundon, Essex, where special attention was given to pupils' "health and character".[9] Following this they lived successively in Wareham, Bodmin, Tregiffian and finally Bryher, Isles of Scilly, where Powell lived until her death from breast cancer in 1965.

Diving career

While working at Wookey Hole, Powell became fascinated with the "archaeological prospects" that were becoming more apparent as a result of advances in diving. She was a strong swimmer and had an "adventurous disposition". She was readily accepted into a newly formed diving group, including leader Graham Balcombe, Frank Frost, Bill Bufton, Bill Tucknott and ‘Digger' Harris,[10] all members of the Mendip Nature Research Society.[11]

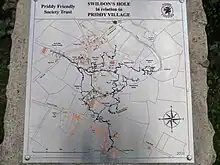

In 1934 Balcombe and fellow diver, Jack Sheppard had made a first attempt at exploring Swildon's Hole, the longest cave in the Mendips. However, a lack of proper equipment forced them to find more suitable gear which came in the form of standard Royal Naval diving dress, including copper helmet, airline and pumps, on loan from Siebe Gorman.[12] The following year they engaged an amateur dive team of "similarly minded individuals" including Powell, with the intention of completing the longest cave dive in British history to that date.[13]

Preparation and the main dive

In July 1935 the team learnt to dive at Priddy Pools where there was both sufficient water and privacy. Powell was third in the diving order for the first attempt and remained submerged for 30 minutes.[14] Seven preparatory dives through Wookey Hole, part of which was opened as a show cave in 1927, laid the groundwork for the main dive.[15]

In an article published in 1953, Balcombe wrote "In the summer of 1935, by the kindness both of the diving firm who lent us the gear and taught us how to use it and of the cave proprietor who gave us every facility, we were able in a series of weekend operations to acquire experience in working underwater which set our feet along the road to conquest."[16]

Balcombe's intention was for the whole team to make the descent, however this quickly became unworkable because of time constraints, so a decision was made to focus on two divers. As team leader, Balcombe was the clear choice for Diver No. 1. However, the other members of the team were all equally game, so the choice of Diver No. 2 was not obvious. Referring to this conundrum, Balcombe wrote, "It was finally decided that the best way was to give the place to the woman of the party, and royally has the choice been justified. Cool, collected, showing no fear, she has carried out every task with an assurance and reliability that none could better." The only difficulty that arose was the ill-fitting suit around her small wrists – the diving suits having been designed to "fit a seaman's wrists".[17]

On Sunday 18 August 1935, Powell accompanied Balcombe on what became the world's longest cave dive at that point, a distance of 52 m (171 ft).[18] taking three hours.[19]

Of her role, Powell said "My part in the show was really an unimportant one. All I had to do was follow behind Mr Balcombe and see that his guide ropes and air line did not become entangled or caught in the various bends and rocks we had to negotiate in walking along the bed of the river."[20] When Balcombe, who dived first, was asked about Powell's role, he explained, "She has to safeguard me against any accidents or sudden drop as I go forward. I am at the end of our line and am proceeding only with the safeguard of No. 2 Diver."[21]

Both divers had microphones fitted in their helmets and the dive was broadcast by the BBC[22] in a programme presented by Francis Worsley.[23] At points there was concern for Powell's safety when she failed to respond to questions. Afterwards she explained that she could not hear on account of the air bubbles, which "drowned the microphone".[24] After returning to the surface she told the BBC "It has been thrilling and I have enjoyed it." Of her dive, Herbert E. Balch, pioneer of modern caving techniques, said "Mrs Powell's willingness to make the journey was the pluckiest adventure I have ever seen undertaken by a woman."[25]

The Log

Powell and Balcombe co-wrote what was to become the first cave-diving book, The Log of the Wookey Hole Exploration Expedition: 1935, with Powell contributing the bulk of the text. It was published by The Cave Diving Group in 1936 with a print run of 175 copies. It has subsequently become a much sought-after document, with copies selling for "several hundred pounds."[26] In the log she described the experience:

"slipping down from the enveloping brown atmosphere, we suddenly entered an utterly different world, a world of green, where the water was as clear as crystal. Imagine a green jelly, where even the shadows cast by the pale green boulders are green but of a deeper hue… So still, so silent, unmarked by the foot of man since the river came into being, awe-inspiring though not terrifying, it was like being in some mighty and invisible presence, whose only indication was this saturating greenness."[27]

— Penelope Powell

References

- ↑ "Wookey Hole". ukcaves.co.uk. Retrieved 2022-08-23.

- ↑ Shaw, Trevor; Ballinger, Christine (2020). A Biographical Bibliography: Explorers, Scientist and Visitors in the World's Karst 852BC to the Present. Ljubljana, Slovenia: Založba ZRC. p. 250. ISBN 978-9610504443.

- ↑ "Cave Diving – How it all started". startcaving.co.uk. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- ↑ "Secret River Explored". Dundee Courier. Dundee, UK. 1935-08-19. p. 7.

- ↑ "Tyndell Powell-Hoppe, at Penang, Malay". Western Morning News. Plymouth, UK. 1927-10-03. p. 4.

- ↑ Farr, Martyn (1980). The Darkness Beckons: The History and Development of World Cave Diving. London: Diadem Books. p. 41. ISBN 1910240745.

- ↑ "New Caverns Discovered". Wells Journal. Wells, UK. 1935-08-23. p. 3.

- ↑ "Hidden River Bed Explored". Aberdeen Press and Journal. Aberdeen, UK. 1935-08-19. p. 6.

- ↑ "Tankerton School". Chelmsford Chronicle. Chelmsford, UK. 1937-12-17. p. 8.

- ↑ Farr, Martyn (1980). The Darkness Beckons: The History and Development of World Cave Diving. London: Diadem Books. p. 43. ISBN 1910240745.

- ↑ "A Window on the World". Illustrated London News. London, UK. 1935-08-24. p. 22.

- ↑ Gatacre, E V; Standon, W I (1980). Wookey Hole. Somerset, UK: Wookey Hole Caves Ltd. p. 9.

- ↑ Burgess, Robert Forrest (1976). The Cave Divers. New York, US: Dodd, Meads. p. 18. ISBN 0396072046.

- ↑ Balcombe, Graham; Powell, Penelope (1936). The Log of the Wookey Hole Exploration Expedition 1935. Wells, UK: The Cave Diving Group. p. 28.

- ↑ Balcombe, Graham; Powell, Penelope (1936). The Log of the Wookey Hole Exploration Expedition 1935. Wells, UK: The Cave Diving Group. p. 10.

- ↑ Cullingford, C H D (1953). British Caving: An introduction to speleology. London, UK: Routledge. p. 462.

- ↑ Balcombe, Graham; Powell, Penelope (1936). The Log of the Wookey Hole Exploration Expedition 1935. Wells, UK: The Cave Diving Group. p. 18.

- ↑ "New Caverns Discovered". Wells Journal. Wells, UK. 1935-08-23. p. 3.

- ↑ Special Correspondent (1935-08-19). "Broadcast from the deep". Western Mail. Cardiff, UK. p. 10.

- ↑ Special Correspondent (1935-08-19). "Broadcast from the deep". Western Mail. Cardiff, UK. p. 10.

- ↑ "New Caverns Discovered". Wells Journal. Wells, UK. 1935-08-23. p. 3.

- ↑ "Cave Broadcast". Sheffield Independent. Sheffield, UK. 1935-07-27. p. 7.

- ↑ "New Caverns Discovered". Wells Journal. Wells, UK. 1935-08-23. p. 3.

- ↑ Special Correspondent (1935-08-19). "Broadcast from the deep". Western Mail. Cardiff, UK. p. 10.

- ↑ "New Caverns Discovered". Wells Journal. Wells, UK. 1935-08-23. p. 3.

- ↑ Balcombe, Graham; Powell, Penelope (2009). The Log of the Wookey Hole Exploration Expedition 1935. Wells, UK: The Cave Diving Group. p. 3. ISBN 9780901031068.

- ↑ Lovelock, James (1981). A Caving Manual. London, UK: Batsford. p. 67. ISBN 0713419040.

Further reading

- The Darkness Beckons (1980) Martyn Farr. Pub: Diadem Books

- The Log of the Wookey Hole Exploration Expedition: 1935 (2009) Graham Balcombe and Penelope Powell. Pub: The Cave Diving Group. ISBN 9780901031068