In linguistics, a treebank is a parsed text corpus that annotates syntactic or semantic sentence structure. The construction of parsed corpora in the early 1990s revolutionized computational linguistics, which benefitted from large-scale empirical data.[1]

Etymology

The term treebank was coined by linguist Geoffrey Leech in the 1980s, by analogy to other repositories such as a seedbank or bloodbank.[2] This is because both syntactic and semantic structure are commonly represented compositionally as a tree structure. The term parsed corpus is often used interchangeably with the term treebank, with the emphasis on the primacy of sentences rather than trees.

Construction

Treebanks are often created on top of a corpus that has already been annotated with part-of-speech tags. In turn, treebanks are sometimes enhanced with semantic or other linguistic information. Treebanks can be created completely manually, where linguists annotate each sentence with syntactic structure, or semi-automatically, where a parser assigns some syntactic structure which linguists then check and, if necessary, correct. In practice, fully checking and completing the parsing of natural language corpora is a labour-intensive project that can take teams of graduate linguists several years. The level of annotation detail and the breadth of the linguistic sample determine the difficulty of the task and the length of time required to build a treebank.

Some treebanks follow a specific linguistic theory in their syntactic annotation (e.g. the BulTreeBank follows HPSG) but most try to be less theory-specific. However, two main groups can be distinguished: treebanks that annotate phrase structure (for example the Penn Treebank or ICE-GB) and those that annotate dependency structure (for example the Prague Dependency Treebank or the Quranic Arabic Dependency Treebank).

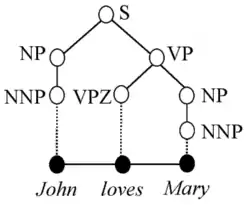

It is important to clarify the distinction between the formal representation and the file format used to store the annotated data. Treebanks are necessarily constructed according to a particular grammar. The same grammar may be implemented by different file formats. For example, the syntactic analysis for John loves Mary, shown in the figure on the right, may be represented by simple labelled brackets in a text file, like this (following the Penn Treebank notation):

(S (NP (NNP John))

(VP (VPZ loves)

(NP (NNP Mary)))

(. .))

This type of representation is popular because it is light on resources, and the tree structure is relatively easy to read without software tools. However, as corpora become increasingly complex, other file formats may be preferred. Alternatives include treebank-specific XML schemes, numbered indentation and various types of standoff notation.

Applications

From a computational linguistics[3] perspective, treebanks have been used to engineer state-of-the-art natural language processing systems such as part-of-speech taggers, parsers, semantic analyzers and machine translation systems.[4] Most computational systems utilize gold-standard treebank data. However, an automatically parsed corpus that is not corrected by human linguists can still be useful. It can provide evidence of rule frequency for a parser. A parser may be improved by applying it to large amounts of text and gathering rule frequencies. However, it should be obvious that only by a process of correcting and completing a corpus by hand is it possible then to identify rules absent from the parser knowledge base. In addition, frequencies are likely to be more accurate.

In corpus linguistics, treebanks are used to study syntactic phenomena (for example, diachronic corpora can be used to study the time course of syntactic change). Once parsed, a corpus will contain frequency evidence showing how common different grammatical structures are in use. Treebanks also provide evidence of coverage and support the discovery of new, unanticipated, grammatical phenomena.

Another use of treebanks in theoretical linguistics and psycholinguistics is interaction evidence. A completed treebank can help linguists carry out experiments as to how the decision to use one grammatical construction tends to influence the decision to form others, and to try to understand how speakers and writers make decisions as they form sentences. Interaction research is particularly fruitful as further layers of annotation, e.g. semantic, pragmatic, are added to a corpus. It is then possible to evaluate the impact of non-syntactic phenomena on grammatical choices.

In linguistics research, annotated treebank data has been used in syntactic research to test linguistic theories of sentence structure against large quantities of naturally occurring examples.

Semantic treebanks

A semantic treebank is a collection of natural language sentences annotated with a meaning representation. These resources use a formal representation of each sentence's semantic structure. Semantic treebanks vary in the depth of their semantic representation. A notable example of deep semantic annotation is the Groningen Meaning Bank, developed at the University of Groningen and annotated using Discourse Representation Theory. An example of a shallow semantic treebank is PropBank, which provides annotation of verbal propositions and their arguments, without attempting to represent every word in the corpus in logical form.

Syntactic treebanks

Many syntactic treebanks have been developed for a wide variety of languages:

To facilitate the further researches between multilingual tasks, some researchers discussed the universal annotation scheme for cross-languages. In this way, people try to utilize or merge the advantages of different treebanks corpora. For instance, The universal annotation approach for dependency treebanks;[10] and the universal annotation approach for phrase structure treebanks.[11]

Search tools

One of the key ways to extract evidence from a treebank is through search tools. Search tools for parsed corpora typically depend on the annotation scheme that was applied to the corpus. User interfaces range in sophistication from expression-based query systems aimed at computer programmers to full exploration environments aimed at general linguists. Wallis (2008) discusses the principles of searching treebanks in detail and reviews the state of the art around that time.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ Alexander Clark, Chris Fox and Shalom Lappin (2010). The handbook of computational linguistics and natural language processing. Wiley.

- ↑ Sampson, G. (2003) ‘Reflections of a dendrographer.’ In A. Wilson, P. Rayson and T. McEnery (eds.) Corpus Linguistics by the Lune: A Festschrift for Geoffrey Leech, Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, pp. 157-184

- ↑ Haitao Liu, Wei Huang — A Chinese Dependency Syntax for Treebanking, published by Communication University of China, published (online) by the Association for Computational Linguistics - accessed 2020-2-4

- ↑ Kübler, Sandra; McDonald, Ryan; Nivre, Joakim (2008-12-18). "Dependency Parsing". Synthesis Lectures on Human Language Technologies. 2 (1): 1–127. doi:10.2200/s00169ed1v01y200901hlt002.

- ↑ Kais Dukes (2013) Semantic Annotation of Robotic Spatial Commands. Language and Technology Conference (LTC). Poznan, Poland.

- ↑ Celano, Giuseppe G. A. 2014. Guidelines for the annotation of the Ancient Greek Dependency Treebank 2.0. https://github.com/PerseusDL/treebank_data/edit/master/AGDT2/guidelines

- ↑ Mambrini, F. 2016. The Ancient Greek Dependency Treebank: Linguistic Annotation in a Teaching Environment. In: Bodard, G & Romanello, M (eds.) Digital Classics Outside the Echo-Chamber: Teaching, Knowledge Exchange & Public Engagement, Pp. 83–99. London: Ubiquity Press. doi:10.5334/bat.f

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dag Haug. 2015. Treebanks in historical linguistic research. In Carlotta Viti (ed.), Perspectives on Historical Syntax, Benjamins, 188-202. A preprint is available at http://folk.uio.no/daghaug/historical-treebanks.pdf.

- ↑ Bamman David & al. 2008. Guidelines for the Syntactic Annotation of Latin Treebanks (v. 1.3). http://nlp.perseus.tufts.edu/syntax/treebank/1.3/docs/guidelines.pdf

- ↑ McDonald, R.; Nivre, J., Quirmbach-Brundage, Y.; et al. "Universal Dependency Annotation for Multilingual Parsing.". Proceedings of the ACL 2013.

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Han, A.L.-F; Wong, D.F.; Chao, L.S.; Lu, Y.; He, L. & Tian, L. (2014). "A Universal Phrase Tagset for Multilingual Treebanks" (PDF). Proceedings of the CCL and NLP-NABD 2014, LNAI 8801, pp. 247– 258. © Springer International Publishing Switzerland. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-12277-9_22.

- ↑ Wallis, Sean (2008). Searching treebanks and other structured corpora. Chapter 34 in Lüdeling, A. & Kytö, M. (ed.) Corpus Linguistics: An International Handbook. Handbücher zur Sprache und Kommunikationswissenschaft series. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.