| Pennsylvania State Capitol sculpture groups | |

|---|---|

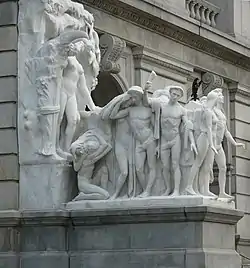

The Burden of Life: The Broken Law | |

| Artist | George Grey Barnard Piccirilli Brothers (carvers) |

| Year | commissioned 1902 dedicated October 4, 1911 |

| Medium | Carrara marble |

| Location | Harrisburg, Pennsylvania |

| Owner | Pennsylvania State Capitol |

Pennsylvania State Capitol sculpture groups are a pair of larger-than-life, multi-figure groups by American sculptor George Grey Barnard, that flank the west entrance to the Pennsylvania State Capitol in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Barnard was commissioned to create the sculptures in 1902, and modeled them in clay and plaster over several years in France.[1] Piccirilli Brothers carved them in white Carrara marble in New York City, and installed the finished sculptures at the Capitol in 1911.[1]

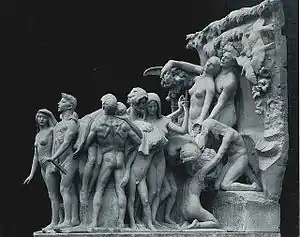

The south group is titled The Burden of Life: The Broken Law, and is overseen by a heroic size bas relief of Adam and Eve. It portrays life struggles and negative emotions – widowhood, toil, grief, despair – but with the possibility of consolation and hope. The north group is titled Love and Labor: The Unbroken Law, and is overseen by a heroic size bas relief of a prosperous farmer and his wife. It portrays life accomplishments and positive emotions – familial love, education, parenthood, religion – and the promise of the future generation.

History

Joseph Miller Huston, the Capitol's architect, chose Barnard in 1902 to create exterior sculpture for the building. The initial sculpture program, conceived by Barnard and Huston, called for eight sculpture groups – a pair flanking each of the building's four entrances – as well as an "enormous bronze composition along the skyline of the main entrance façade." The latter was to represent the Apotheosis of Labor and be supported by four pairs of caryatids depicting different types of laborers. The groups flanking the main entrances on the east and west facades were to depict "primitive people." The groups flanking the entrances to the House and Senate wings (on the west façade) were to depict early settlers of Pennsylvania— English, Quakers, Scotch-Irish, and Germans.[2] The estimated cost for this program, about $700,000, was enough to ensure that it was never executed. By the time Barnard signed a three-year contract in December 1902, the sculpture program had been reduced to the two large groups flanking the main entrance (west façade), and his fee had been reduced to $300,000. The sculptor and his family then moved to France, where they obtained a large barn that was converted into a studio in which the groups were created.[3]

In his studio at Moret-sur-Loing Barnard hired as many as fifteen assistants, including a plaster caster who transformed Barnard's clay figures into plaster. However, the contracted funds were slow in arriving and eventually stopped, and in 1906 a huge scandal erupted involving massive financial irregularities that eventually landed Huston and others in jail. Barnard's assistants continued to work for him in the hope that they would eventually be paid, and this was accomplished by Barnard's collecting old Gothic and Romanesque sculpture remnants from the French countryside and selling them.[4] There remained the problem of purchasing the marble that would be needed to carve the figures. Eventually, a group of New York luminaries advanced funds for that purpose, as well as paying the bond that Barnard had lost because he had not delivered the works on time.[2]

1908 Boston exhibition

Five heroic-size plaster sculptures for the Pennsylvania Capitol groups – The Prodigal Son, Brothers, The Young Parents, Kneeling Youth, Forsaken Mother – were part of an exhibition of Barnard's work at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in October–November 1908.[5] Also exhibited were his plaster scale models of the complete sculpture groups.[6] In a review in The International Studio, critic J. Nilsen Laurvik compared Barnard to Auguste Rodin and the recently deceased Augustus Saint-Gaudens, concluding: "[H]e is the one man most needed in the art life of our country; his work is like an invigorating breath of fresh sea air that must surely have its influence in giving a more vital and higher meaning to both life and art. ... [H]e is a unique personality in the art life of our country and one of the few truly great sculptors of our time."[7] Critic William Howe Downes also enthusiastically praised his work:

Wherever Mr. Barnard touches humanity in his work, it is with the desire and the power to glorify it, to show its greatness, to bring out all that is heroic and tender and lovable in it. Nothing is more certain than that this is understood, that the appeal has met with an instant response.

The understanding thus established between the artist and his public is the more to be welcomed because, up to a quite recent period, it had been felt by many observers that the modern school of sculpture was a hollow sort of survival, without much reason for being. Saint-Gaudens did much to modify such an impression in this country by uniting in a serious and touching way the strands of national consciousness with aesthetic sensibility. It remained for Mr. Barnard to create a still more universal artistic language for still more universal ideas, and to place before us the nude human being transformed into new shapes of undying beauty and majesty.[5]

1910 Paris Salon

The groups were carved in marble by the Piccirilli Brothers in New York City in 1909 and 1910,[2] and shipped to France to make their public debut at the Paris Salon.

Barnard's sculpture groups were given the place of honor at the 1910 Salon de Champ de Mars at the Gran Palais in Paris.

Nudity controversy

Barnard's vision of twin sculpture groups of profuse nude figures was controversial from the start.[8] Each group was composed of 8 individual sculptures featuring 1 to 4 figures.[9] Of the 30 total figures, 27 were nude & dash; the angel was gowned, and both infants were swaddled in cloth.

Some Pennsylvania legislators and local religious leaders opposed the nudity of Barnard's sculptures.[8] He responded:

There has been some criticism because these 30 figures I have executed are nude. Only in the nude could I have given adequate expression to these figures. Drapery would have spoiled the effect. Only through delineation of the nude human form can great emotions be shown. You cannot drape a symbolic figure in an overcoat and expect it to be anything but a marble dummy.

It is curious that this criticism should come from men, while women approve of the work as is. Women have better artistic sense than men. They are inspired by the human form, but men are not similarly inspired. They think the nude is suggestive. I understand that the Pennsylvania state authorities are going to drape them. I shall make no protest, but I am sorry.[10]

Initially, plaster of Paris short trousers were applied to the male figures, but the results proved unsatisfactory.[11] Two tents were erected on Friday, May 12, 1911, one around each sculpture group, to mask that day's removal of the plaster trousers.[11] On Sunday, the canvas walls of the tents were cut down by art lovers who wished to view the sculptures before plaster loincloths were applied on Monday— "the great majority of the crowd being women," according to The Chicago Tribune.[11] Instead of short trousers or loincloths, the Piccirilli Brothers carved marble sheaths to cover the genitals of the male figures, for which they charged $118.50.[8]

1911 dedication

The sculptures were installed by Giulio Piccirilli. Their official unveiling was on October 4, 1911.[2]

The Prodigal Son

Barnard exhibited a marble version of The Prodigal Son at the Armory Show in 1913.[12] That sculpture is now in the collection of the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[13] Another marble version is in the collection of the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky.[14]

Keys

South group – The Burden of Life: The Broken Law[15]

North group – Love and Labor: The Unbroken Law[16]

References

- 1 2 Harold E. Dickson, "Barnard's Sculptures for the Pennsylvania Capitol," The Art Quarterly, vol. 22, no. 2 (April 1959), pp. 127-147.

- 1 2 3 4 Wayne Craven, Sculpture in America (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1968), pp. 446-448.

- ↑ Frederick C. Moffatt, Errant Bronzes: George Grey Barnard's Statues of Abraham Lincoln, University of Delaware Press, Newark, 1998.

- ↑ "Barnard's Mighty sculptures for the Pennsylvania Capitol," Current Literature, vol. 49, no. 2 (August 1910), pp. 207-09.

- 1 2 William Howe Downes, "Mr. Barnard's Exhibit in Boston, Which Appealed to the Connoisseur and the Crowd Alike," The World's Work, vol. 17, no. 4 (February 1909), pp. 11267-11269.

- ↑ Ernest Knaufft, "George Grey Barnard: A Virile American Sculptor," The American Review of Reviews, vol. 38, no. 6 (December 1908), pp. 689-92.

- ↑ J. Nilsen Laurvik, "George Grey Barnard," The International Studio, vol. 36, no. 142 (December 1908), pp. 39-48.

- 1 2 3 Robert Swift, "The Price of Prudity in 1911," Archived 2017-03-03 at the Wayback Machine The Political Express, September 25, 2011.

- ↑ George Grey Barnard, from Pennsylvania Capitol Preservation Committee.

- ↑ "Defends Nude in Statuary," The Alexandria Gazette, April 25, 1911, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 "Women in Fight to See Nude Art," The Chicago Tribune, May 15, 1911, p. 2.

- ↑ Brown, Milton W., The Story of the Armory Show, The Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation, 1963, p. 221.

- ↑ The Prodigal Son (Carnegie Art Museum), from SIRIS.

- ↑ The Prodigal Son (Speed Art Museum), from SIRIS.

- ↑ The Burden of Life: The Broken Law, from SIRIS.

- ↑ Love and Labor: The Unbroken Law, from SIRIS.

External links

Media related to Pennsylvania State Capitol sculpture groups at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pennsylvania State Capitol sculpture groups at Wikimedia Commons