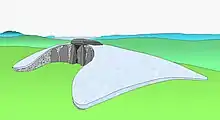

Pentre Ifan Dolmen – side view | |

Pentre Ifan, within Nevern Community, Pembrokeshire | |

| Alternative name | Pentre Ifan Cromlech |

|---|---|

| Location | 1km south of Pentre Ifan hamlet, in Pembrokeshire National Park. (OS Grid ref SN099370) |

| Region | West Wales |

| Coordinates | 51°59′56″N 4°46′12″W / 51.9990°N 4.7700°W |

| Type | Dolmen |

| History | |

| Periods | Neolithic |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1936-37, 1958–59 |

| Archaeologists | William Francis Grimes |

| Condition | Excellent |

| Public access | Yes |

| Website | CADW site page |

| Official name | Pentre-Ifan Burial Chamber[1] |

| Reference no. | PE008[1] |

Pentre Ifan (literally "Evan's Village") is the name of an ancient manor in the community and parish of Nevern, Pembrokeshire, Wales. It is 11 miles (18 km) from Cardigan, Ceredigion, and 3 miles (4.8 km) east of Newport, Pembrokeshire. Pentre Ifan contains and gives its name to the largest and best preserved neolithic dolmen in Wales.

The Pentre Ifan monument is a scheduled monument and is one of three Welsh monuments to have received legal protection under the Ancient Monuments Protection Act 1882. The dolmen is maintained and cared for by Cadw,[2] the Welsh Historic Monuments Agency.

Toponymy

Welsh: Pentre Ifan translates to "Ifan's village" – from pentref – pen head, and tref town.

The monument

As it now stands, the Pentre Ifan Dolmen is a collection of seven principal stones. The largest is the huge capstone, 5 m (16 ft) long, 2.4 m (7.9 ft) width and 0.9 m (3.0 ft) thick.[3] It is estimated to weigh 16 tonnes and rests on the tips of three other stones, some 2.5 m (8.2 ft) off the ground.[4] There are six upright stones, three of which support the capstone. Of the remaining three, two portal stones form an entrance and the third, at an angle, appears to block the doorway.[5]

Original use

The dolmen dates from around 3500 BC, and has traditionally been identified as a communal burial. Under this theory the existing stones formed the portal and main chamber of the tomb, which would originally have been covered by a large mound of stones about 30 m (98 ft) long and 17 m wide.[4] Some of the kerbstones, marking the edge of the mound, have been identified during excavations. The stone chamber was at the southern end of the long mound, which stretched off to the north. Very little of the material that formed the mound remains.[4] Some of the stones have been scattered, but at least seven are in their original position. An elaborate entrance façade surrounding the portal, which may have been a later addition,[6] was built with carefully constructed dry stone walling. Individual burials are thought to have been made within the stone chamber, which would be re-used many times.[6] No traces of bones were found in the tomb, raising the possibility that they were subsequently transferred elsewhere.

Alternative theory

A major study by Cummings and Richards in 2014 produced a different explanation for the monument.[7] They identify several distinctive attributes shared by the class of monument known as dolmens, all of which are particularly well exemplified at Pentre Ifan.

First, such monuments typically have a large capstone derived from a glacial erratic, far bigger than is required or sensible if the aim is to roof a chamber. Furthermore, the capstone has a flat underside. Sometimes, as here, this has been arrived at by splitting the rock; at other sites, such as Garn Turne, some 12 km to the south-west, it has been laboriously 'pecked' off using stone tools.[8] The capstone is supported on the tapering tips of slender uprights. As at Pentre Ifan, there are often other stones within the group, but they play no part in holding up the capstone, and the resulting effect of the enormous stone appearing to float above the other stones would seem to be deliberate and desired.[8] If these are the key elements of the monument then, it is argued, the stones were never designed to be buried within a mound, and they never formed a chamber to contain bones. What we see today is the monument as it was intended to be seen.[9] It might therefore represent a more elaborate version of a standing stone. Its purpose could be simply to demonstrate the status and skill of the builders, or to add significance and gravitas to an already significant place.[10]

Construction technique

The sheer size of the huge capstone that is supported by the larger dolmens makes it overwhelmingly likely that the stone was not brought in from elsewhere, but already stood as an independent glacial erratic on the same spot it now occupies. Evidence from the 1948 excavation is compatible with the idea of a large pit being dug at Pentre Ifan, to expose and work on the stone, perhaps splitting it to create a flat underside, It could then be levered vertically upwards a little at a time, using poles, ropes, and large numbers of people, and packed into place using a growing heap of boulders. Once at the required height, the supporting uprights could be introduced, and the boulders removed to leave only the uprights, and such other surrounding stones as were wanted,[11] or for sacrificial ceremonies.

Archaeology

Pentre Ifan was studied by early travellers and antiquarians, and rapidly became famous as an image of ancient Wales,[12] from engravings of the romantic stones.[5] George Owen wrote of it in enthusiastic terms in 1603, and Richard Tongue painted it in 1835.[13]

The first United Kingdom legislation to protect ancient monuments was passed in 1882, and 'The Pentre Evan Cromlech' (as it was styled) was on the initial list of 68 protected sites – one of only three in Wales.[14] On 8 June 1884, two years after the passing of the first Ancient Monuments Act, Augustus Pitt Rivers, Britain's first Inspector of Ancient Monuments, made a visit and produced sketch plans of the monument.[15] The legal protection the Act gave was limited. It became an offence to remove stones or items from the site, but the owner of a monument was exempt from any prosecution. The Act however provided for the Commissioner of Works to become 'guardian' of a scheduled monument[14] – in effect to own the monument, even though the land on which it stood remained in private ownership. Perhaps as result of Pitt Rivers' visit, this protection was put in place, and the Commissioner of Works and various successor bodies have been guardians of Pentre Ifan ever since.

Archaeological excavations took place in 1936–37 and 1958–59, both led by William Francis Grimes. This identified rows of ritual pits which lay under the mound, and therefore must predate it. Kerbstones for the mound were also found, but not in a complete sequence, and aligned more to the pits than to the stone chamber.[13] Very few items were found in the excavations, other than some flint flakes, and a small amount of Welsh (Western) pottery.[13]

The dolmen is maintained and cared for by Cadw,[2] the Welsh Historic Monuments Agency. The site is well kept, and entrance is free. It is about 11 miles (18 km) from Cardigan, and 3 miles (4.8 km) east of Newport, Pembrokeshire.

- Pentre Ifan

See also

References

- 1 2 Cadw. "Pentre-Ifan Burial Chamber (PE008)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- 1 2 "Cadw website". Archived from the original on 21 August 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2006.

- ↑ DAT PRN: 1471 Dyfed Archaeological Trust – Archwilio Database

- 1 2 3 "Pentre Ifan Chambered Tomb, Near Nevern (101450)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- 1 2 "Pentre Ifan". The Megalithic Portal.

- 1 2 stonepages.com Accessed 7 June 2014

- ↑ Cummings, Vicki; Richards, Colin (2014). "The essence of the dolmen: the Architecture of megalithic construction". Préhistoires Méditerranéennes (En ligne). Colloque – 2014 Functions, uses and representations of space in the monumental graves of Neolithic Europe. Association pour la promotion de la préhistoire et de l'anthropologie méditerranéennes (published 29 October 2014). ISSN 1167-492X. Retrieved 22 May 2015. (text is in English)

- 1 2 Cummings & Richards 2014, para 13.

- ↑ Cummings & Richards 2014, para 15.

- ↑ Cummings & Richards 2014, para 26.

- ↑ Cummings & Richards 2014, para 20.

- ↑ www.bluestonewales.com, accessed 7 June 2014

- 1 2 3 www.rock-art-in-wales.co.uk Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 7 June 2014

- 1 2 Hunter, Robert (1907). . The Preservation of Places of Interest or Beauty. Manchester University Press – via Wikisource.

- ↑ British Archaeology Magazine: News Archived 18 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Issue 108, Sep/Oct 2009

External links

- Photos of Pentre Ifan and surrounding area, geograph.org; accessed June 4, 2020.

- The best preserved megalithic site in Wales – Extrageographic

- Article and photos of Pentre Ifan

- Images, megalithic.co.uk; accessed June 4, 2020.