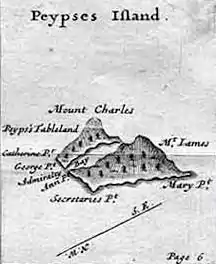

Pepys Island in detail (William Hacke, 1699, Collection of Original Voyages) | |

Pepys Island depicted on an 18th-century map. Roche Island is South Georgia. (R. W. Seale, ca. 1745, fragment) | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 47°S 59°W / 47°S 59°W |

Pepys Island /ˈpiːps/ is a phantom island, once said to lie about 230 nautical miles (260 mi; 430 km) north of the Falkland Islands at 47°S.[1] Pepys Island is now believed to have been a misidentified account of the Falkland Islands.

Original identification

In December 1683 the British corsair William Ambrose Cowle(y), master of the Bachelor's Delight, a ship of 40 guns proceeding on a circumnavigation of the globe, discovered at a latitude stated as 47°S a previously uncharted and unpopulated island in the South Atlantic which he named "Pepys Island", for Samuel Pepys, Secretary to the Admiralty. His companion on the voyage, William Dampier, considered the sighting to be the "Sebaldinas Islands", an alternative name at the time for the Falklands. Cowle's log entry reads:[2]: 34

- We continued to the SW to 47°S where we saw an unknown and uninhabited island which I named Pepys. It is a good place for fresh water and tinder. Its harbour is excellent with safe anchorage for a thousand ships. We saw an enormous number of birds on this island and we believe that there will be abundant fishing around its coasts, for they are surrounded by a bottom of sand and shingle.

There is a later manuscript elaborating the log entry:

- Jan 1683OS. In this month we arrived at latitude 47°40′S and noticed an island to our west with the wind ENE. We headed towards it but as it was very late to approach the coast spent the night off the cape. The island had a pleasant aspect: there were woods, one might even say it was totally wooded. To the east of the island was a rock on which there were a large number of birds the size of small ducks. Our crew hunted them as our ship passed by and killed as many as we needed for food: they were quite tasty but spoiled by the fishy flavour.

- I put the bow to the south and sailed round the island. On the SW coast I found a comfortable harbour to anchor. I wanted to put out a pinnace to reconnoitre but the wind was blowing so fiercely that it would have been dangerous. Continuing on the same course while sounding we measured depths of 26 and 27 fathoms except where we found much seawood adrift, and here we sounded only seven fathoms.

- We feared stopping for long in shallows with a seabed of shingle, but the harbour was vast, able to accommodate at least 500 ships. Its entrance was narrow and we found no great depth in the northern part, but without doubt ships can enter without danger at the southern end because the bottom is deeper there: however it would be necessary to find a channel with sufficient water at all states of the tide for ships to enter.

- I should have liked to have spent the night in the lee of the island but the purpose of my voyage was not to make discoveries. That same afternoon we saw another island which made me think that perhaps these were the Sebaldes. We then sailed WSW, a corrected course for the SW because the needle was off by 22° to the east.

Later attempts to locate the island

The original official historian of record,[2]: 35 Pedro de Angelis, wrote in 1839 that this was so far north of the Falklands it was "absurd" to think that an experienced navigator could have made such an error as to put himself four degrees of latitude more northerly, and in high summer. Many expeditions attempted unsuccessfully to locate the island during the eighteenth century. These included: Lord Anson (1740–1744 voyage), Commodore Byron (1764), Captain Cook (both voyages), Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander (1769), Antoine-Joseph Pernety (1763–1764), Louis de Bougainville (1763-1769 voyages), Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse (1785, searching for "The Great Island") and George Vancouver (1790-1795 voyages, also searching for "The Great Island"). In the reports of Byron, Cook and Bougainville[2]: 39 all found themselves in thick sargasso with large flocks of birds overhead. They were searching 80 to 85 leagues both east of the Patagonian coast and north of the Falklands (from 1630–1840 a Spanish league measured three nautical miles) and these may be considered sure signs of the proximity of land. La Pérouse mentioned the seaweed and identified the flocks of birds as albatross and petrels which never approach land except to lay their eggs.

In conclusion to his 1839 introduction to the work of reference, Pedro de Angelis noted that the report of a mercantile master returning to Montevideo from the Falklands came to the attention of the Spanish Minister, who consulted with Don Jorge Juan, head of the Department of the Navy. They identified Pepys Island as being synonymous with Puig, a phantom island sought by the French and known as "the Great Island". This was based on three documents: Cowle's sketch, Puig Island as sketched by the mercantile captain and a plan "of unimpeachable provenance" which he does not name. De Angelis concluded: "In view of the explicit statements made by those who have actually visited the island, those who deny its existence lack authenticity."

The modern editor of the work of reference, Professor Pesatti, dissents[2]: 42 from Pedro de Angelis, particularly on the basis of Cowle's sketch, a document which unfortunately he fails to produce in evidence: "The description of the island coincides in almost all details to the Falklands, and a sketch map by Cowle represents exactly the alignment of these islands with the central strait which divides them."

See also

Notes

- ^ Old Style date (written as January 1684 in New Style)

References

- ↑ James Burney, A Chronological History of the Discoveries in the South Sea Or Pacific Ocean; accessed 25 July 2010

- 1 2 3 4 Antonio de Viedma, Diarios de navegación – expediciones por las costas y ríos patagónicos (1780–1783), Ediciones Continente reprint, Buenos Aires 2006, ISBN 950-754-204-3, with an introduction by Professor Pedro Pesatti, Universidad Nacional de Conahue, Argentina: and two prefaces of importance – Discurso preliminar al diario de Viedma, pp. 19–28, and Apuntes históricos de la Isla Pepys, pp. 33–36 with facsimile map, both authored by Pedro de Angelis, on 20 June 1839. De Angelis (b. Naples 1784, d. Buenos Aires 1859) was the historian who created the State Printing Service. He edited the collection of works and documents relative to the ancient and modern history of the provinces of the River Plate in six volumes (1835–1838).