In urban design, permeability and connectivity are terms that describe the extent to which urban forms permit (or restrict) movement of people or vehicles in different directions. The terms are often used interchangeably, although differentiated definitions also exist. Permeability is generally considered a positive attribute of an urban design, as it permits ease of movement and avoids severing neighbourhoods. Urban forms which lack permeability, e.g. those severed by arterial roads, or with many long culs-de-sac, are considered to discourage movement on foot and encourage longer journeys by car. There is some empirical research evidence to support this view.[2]

Permeability is a central principle of New Urbanism, which favours urban designs based upon the ‘traditional’ (particularly in a North American context) street grid. New Urbanist thinking has also influenced Government policy in the United Kingdom, where the Department for Transport Guidance Manual for Streets says:[3]

Street networks should in general be connected. Connected or ‘permeable’ networks encourage walking and cycling and make places easier to navigate through.

Reservations

There are two principal reservations concerning permeability. The first relates to property crime. Although the issue is contested, there is some research evidence to suggest that permeability may be positively correlated with crimes such as burglary.[4] New research has expanded the discussion on this disputed issue. A recent study[5] did extensive spatial analysis and correlated several building, site plan and social factors with crime frequencies and identified nuances to the contrasting positions. The study looked at, among others, a) dwelling types, b) unit density (site density) c) movement on the street, d) culs–de-sac or grids and e) the permeability of a residential area. Among its conclusions are, respectively, that:

- flats are always safer than houses and the wealth of inhabitants matters;

- density is generally beneficial but more so at ground level;

- local movement is beneficial, larger scale movement not so;

- relative affluence and the number of neighbours has a greater effect than either being on a cul-de-sac or being on a through street; also simple, linear culs-de-sac with good numbers of dwellings that are joined to through streets tend to be safe;

- residential areas should be permeable enough to allow movement in all directions but no more; the over-provision of poorly used permeability is a crime hazard

The second reservation concerns the effects of permeability for private motor vehicles. Melia (2012)[6] proposed the terms "unfiltered permeability" and "filtered permeability" to distinguish between the two approaches.

Unfiltered permeability is the view supported by the New Urbanists that urban designs should follow "traditional" or mixed use streets, where pedestrians, cyclists and motor vehicles follow the same routes. The principal advantage claimed for this approach is that it "leads to a more even spread of motor traffic throughout the area and so avoids the need for distributor roads".[3]

There are also a range of arguments advanced by the proponents of Shared space that where speeds are low, road users should be mixed rather than segregated.

Filtered permeability

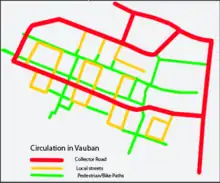

Filtered permeability is the concept, supported by organisations such as Sustrans, that networks for walking and cycling should be more permeable than the road network for motor vehicles. This, it is argued will encourage walking and cycling by giving them a more attractive environment free from traffic and a time and convenience advantage over car driving. Evidence for this view comes from European cities such as Freiburg, and its rail suburb Vauban, and Groningen which have achieved high levels of walking and cycling by following similar principles, sometimes described as: "a coarse grain for cars and a fine grain for cyclists and pedestrians".[6] Filtered permeability requires cyclists, pedestrians (and sometimes public transport) to be separated from private motor vehicles in some places, although it can be combined with shared space, elsewhere in the same town or city. This is the case in Dutch towns such as Drachten.

The principle of filtered permeability was endorsed for the first time in British Government guidance for the eco-towns programme in 2008[7] and later that year by an alliance of 70 organisations concerned with public health, planning and transport in their policy declaration: Take Action on Active Travel.[8]

A parallel debate has been occurring in North America, where researchers have proposed and applied the Fused Grid, an urban street network pattern which follows the principles of filtered permeability, to address perceived shortcomings of both the 'traditional' grid and more recent suburban street layouts. A study conducted in Washington State[9] found that the fused grid was associated with significantly higher levels of walking than the other two alternatives. A recent comparison of seven neighbourhood layouts found a 43 and 32 percent increase in walking with respect to a conventional suburban and the traditional grid in a Fused Grid layout, which has greater permeability for pedestrians than for cars due to its inclusion of pedestrian-only paths (filtering). It also showed a 7 to 10 percent range of reduction in driving with respect to the remainder six neighbourhood layouts in the set.[10]

Permeability and connectivity

Stephen Marshall[1] has sought to differentiate the concepts of "connectivity" and "permeability". As defined by Marshall, "connectivity" refers solely to the number of connections to and from a particular place, whereas "permeability" refers to the capacity of those connections to carry people or vehicles.

Traffic studies on the influence of street patterns on travel generally overlook this distinction and two metrics are instead used to characterize a street pattern for trip purposes: connectivity and intersection density, both of which refer to regular city streets. This omission is often the result of unavailability of data for connectors that do not appear on maps and cannot be geo-coded. Consequently, the potential effect of connectors that are accessible only to pedestrians and bicycles on mode choice and extent of travel is missed. The aforementioned study shows that differentiating between normal paved streets and non-vehicular paths yields clear and positive results about the influence of the latter.[5]

The distinction between permeability and connectivity becomes clearer in practice. Widening roads within a network that lead to destinations would increase the network's permeability, but leave its connectivity unchanged. Conversely, transforming existing streets that are part of a grid plan into permeable, linked culs-de-sac, as was done in Berkeley, CA and Vancouver, BC, retains their connectivity intact but limits their permeability to pedestrians and bicycles only, while it "filters" out motorized transport.

See also

- Bicycle-friendly – Urban planning prioritising cycling

- Cyclability – Degree of the ease of cycling

- Dead end (street) – Street with only one way in and out

- Fifteen minute city – Urban accessibility concept

- Fused grid – Type of urban planning design

- Low Traffic Neighbourhood – Urban planning concept

- Neighborhood effect averaging problem – Source of statistical bias

- Street hierarchy – Urban planning restricting through traffic of automobiles

- Urban vitality – Use intensity of a city space

- Walkability – How accessible a space is to walking

- Walking audit – Assessment of pedestrian accessibility

References

- 1 2 MARSHALL, S., 2005. Streets and Patterns. Spon Press.

- ↑ HANDY, S., CAO, X. and MOKHTARIAN, P.L., 2005. Correlation or causality between the built environment and travel behavior? Evidence from Northern California. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 10(6), pp. 427-444.

- 1 2 DFT, 2007. Manual for Streets. London: Thomas Telford Publishing. Paragraph 4.2.3

- ↑ WHITE, GARLAND F. (1990). "Neighborhood Permeability and Burglary Rates". Justice Quarterly 7(1).

- 1 2 An evidence based approach to crime and urban design Or, can we have vitality, sustainability and security all at once? Bill Hillier, Ozlem Sahbaz March 2008 Bartlett School of Graduate Studies University College London

- 1 2 Melia, S. (2012) Filtered and unfiltered permeability: The European and Anglo-Saxon approaches. Project, 4. pp. 6-9.

- ↑ Eco-towns Transport Worksheet Archived 2011-07-27 at the Wayback Machine, 2008. Town & Country Planning Association and Department of Communities and Local Government.

- ↑ Take Action on Active Travel, published for the working group by Sustrans, Bristol, 2008

- ↑ Frank, L and Hawkins C, 2008, Giving Pedestrians an Edge—Using Street Layout to influence transportation choice, Ottawa, Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation

- ↑ Xiongbing Jin, 2010 Modeling the Influence of Neighbourhood Design on Daily Trip Patterns in Urban Neighbourhoods, Memorial University of Newfoundland

Further reading

- Pafka, E and Dovey, K (2017) "Permeability and interface catchment: measuring and mapping walkable access", Journal of Urbanism 10(2): 150-162

External links

- TDM Encyclopedia, an Australian View on 'roadway connectivity' - contains many further links. Tends towards the conventional view of connectivity with little reference to the reservations outlined here