Phanes of Halicarnassus (Greek: Φάνης) was a wise council man, a tactician, and a mercenary from Halicarnassus, serving the Egyptian pharaoh Amasis II (570–526 BC). Most of what history recounts of Phanes is from the account of Herodotus in his grand historical text, the Histories. According to Herodotus, Phanes of Halicarnassus was "a resourceful man and a brave fighter" serving Amasis II on matters of state, and was well connected within the Egyptian pharaoh's troops. Phanes of Halicarnassus was also very well respected within the military and royal community of Egypt.[2][3]

According to Herodotus, a series of events (which he omits to explain, or does not know for sure) led to Phanes of Halicarnassus falling out of favor with Amasis II. Phanes, disgruntled with the pharaoh deserted Egypt and travelled by ship with the intention of speaking with the Persian emperor Cambyses II. When news reached Amasis II, it caused him great anxiety, leading to him sending his most trustworthy eunuch after Phanes, with the intent of capture or assassination. Phanes originally escaped the assassin, but was eventually captured by him in Lycia. Phanes being of wise mind, however managed to escape by getting the eunuch guards drunk and escaping to Persia. Upon his arrival, he met with a resolute Cambyses II who was about to set out to conquer Egypt but was not sure of the best path possible.

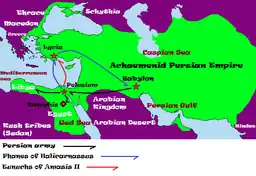

Knowing of the Egyptian way, Phanes of Halicarnassus wisely advised the Persian king to send a messenger to the Arabian Kings and ask for safe passage to Egypt. Arabs gladly complied blessing Cambyses II on his journey and allowed him a safe passage. Phanes would eventually play a critical role in the strategic advancement of the Persian king who eventually defeated Amasis's son Psamtik III, in the battle of Pelusium in 525 BC.

Background

In order to understand the importance of Phanes of Halicarnassus, one has to understand the circumstances surrounding and leading to the battle of Pelusium, and the importance of his council in allowing Cambyses II the easiest path to Egypt.

After the defeat of the Lydian, Median, and Neo-Babylonian empire by Cyrus the Great the Persian empire was a powerful empire stretching from the Indus in the east, to the Northern Arabian deserts and Red Sea in the west, right at the door steps of Egypt. Cyrus the Great would die in battle before he could incorporate Egypt into the empire, but it would be his son, Cambyses II's task to conquer the pharaohs. The background against which Herodotus describes the events leading to the Battle of Pelusium require one to understand the political tensions of the time.[2][3]

Herodotus recounts of one possible motive for Cambyses II desire to conquer Egypt: According to Herodotus, Amasis II came to power by bloody means by defeating, and murdering his predecessor pharaoh Apries. While in power, Amasis, was requested by either Cyrus the Great, or Cambyses II for the best Egyptian eye doctor. Amasis II complied, but did so at the expense of forcing the physician to leave his family and children behind and forcibly sent him to Persia. In an attempt to exact revenge for this unjust exile, the Egyptian ophthalmologist, persuaded king Cambyses II to strengthen his bonds with Egypt through marriage with the daughter of Amasis II. Cambyses II complied and asked Amasis II for his daughters's hand in marriage.

Unable to let go of his favourite daughter, and unwilling to make an enemy of the mighty Persians, Amasis conducted a trickery during which he sent the daughter of the ex-Pharaoh Apries, whom his death he had facilitated by means of bloody revolt, to Persia as his own daughter. This daughter, Nitetis, who was described by Herodotus as being "tall and beautiful", was dressed in fine Egyptian clothing and sent to Persia under pretence of the princess of Egypt. Upon arrival, Cambyses II greeted the princess as daughter of Amasis, at which point she exposed Amasis's ill plan and how he had sent the only surviving daughter of the man he had helped murder to wed the king of Persia, under pretence of royal blood. This infuriated Cambyses II, who immediately set out to move toward Egypt to punish Amasis for this insult. It was at this politically tense, moment that Phanes of Halicarnassus arrived at Persia, and gave Cambyses the confidence to invade Egypt for full conquest.[3][5]

Folk story

Unrelated to Phanes, Herodotus also describes a few untrue stories that he has heard about the reasons for invasion of Egypt. Herodotus in particular describes a story that he explains is at best an "unbelievable" concoction about the reason why Cambyses II attacked Egypt. According this version, after the arrival of the Nitetis, Cassandane wife of Cyrus the Great and mother of Cambyses II, must have felt uncomfortable about the tall Egyptian woman. At one point, one of the Persian women who visited Cassandane comments on how beautiful and tall her children including Cambyses II looked at which point Cassandane replies in disdain of the arrival of Nitetis: "Although I have borne him children like this, Cyrus treats me with no respect and prefers the new arrival from Egypt" at which point Cambyses II, then only ten, who was an audience in the conversation, in defense of Cassandane's honor, says, "that is exactly why when I grow up I am going to turn Egypt upside down."[2]

Family and fate

According to Herodotus, Phanes led Cambyses II to Egypt to face Amasis. Amasis, having died six month before the arrival of the Persian army, was instead represented by his heir and son, Psamtik III (Psammenitus) who had now waged an army of Egyptians anticipating the approaching Persian army. Callous in both strategy, and diplomacy, Psamtik III would lead the Egyptian army to their demise and their eventual siege at Memphis followed by his own capture. Phanes successfully helps lead the Persian armies as an advisor and a mercenary and sees Amasis die of natural causes, and his son chained. This was not to be without tragedy for Phanes however.[2][3]

Herodotus describes that in desperation, and in a violent act to avenge the betrayal, Psamtik III would trick Phanes's sons to see him. He would then kill them all, draining their blood, mixing it with wine, drinking of it and feeding it to all the council members as a sign of what is to come for all those who betray him. Herodotus describes how Psamtik III's lack of diplomacy and violent temper would eventually cost him his life in Persian captivity as he tries to yet again arrange a revolt against Cambyses II, at which point, Cambyses orders his execution. Phanes for most part would stay loyal to Cambyses II after the invasion of Egypt assisting him to come to a diplomatic truce with Libyans.[3]

Parties involved with Phanes

Cambyses II: King of Persia (Lydia, Babylonia, Persis, Anshan, and Media). Captor and executor of Psamtik III.

Amasis II: Pharaoh of Egypt, successor and murderer of Apries.

Psamtik III: Successor and son of Amasis II; murderer of Phanes's sons.

Nitetis: Apries's daughter presented as the false Egyptian princess.

Cassandane: Mother of Cambyses II, and queen consort of emperor Cyrus the Great.

Sources

- ↑ CNG: IONIA, Ephesos. Phanes. Circa 625-600 BC. EL Trite (14mm, 4.67 g).

- 1 2 3 4 Herodotus (Trans.) Robin Waterfield, Carolyn Dewald (1998). The Histories. Oxford University Press, US. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-19-158955-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Herodotus (1737). The History of Herodotus Volume I,Book II. D. Midwinter. pp. 246–250.

Herodotus Amasis.

- ↑ Colbert C. Held (2000). Middle East patterns: places, peoples, and politics. Westview Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 9780813334882.

achaemenid empire map.

- ↑ Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (1837). Manners and customs of the ancient Egyptians: including their private life, government, laws, art, manufactures, religions, and early history; derived from a comparison of the paintings, sculptures, and monuments still existing, with the accounts of ancient authors. Illustrated by drawings of those subjects, Volume 1. J. Murray. pp. 195.

death of Amasis Herodotus.