Pharmacy automation involves the mechanical processes of handling and distributing medications. Any pharmacy task may be involved, including counting small objects (e.g., tablets, capsules); measuring and mixing powders and liquids for compounding; tracking and updating customer information in databases (e.g., personally identifiable information (PII), medical history, drug interaction risk detection); and inventory management. This article focuses on the changes that have taken place in the local, or community pharmacy since the 1960s.

History

Dispensing medications in a community pharmacy before the 1970s was a time-consuming operation. The pharmacist dispensed prescriptions in tablet or capsule form with a simple tray and spatula. Many new medications were developed by pharmaceutical manufacturers at an ever-increasing pace, and medications prices were rising steeply. A typical community pharmacist was working longer hours and often forced to hire staff to handle increased workloads which resulted in less time to focus on safety issues. These additional factors led to use of a machine to count medications.[1]

The original electronic portable digital tablet counting technology was invented in Manchester, England between 1967 and 1970 by the brothers John and Frank Kirby.

I had the original idea of how the machine would work and it was my patent, but it was a joint effort getting it to work in a saleable form. It was 3 years of very hard work. I had originally studied heavy electrical engineering before changing over to Medical School and qualifying as a Medical Doctor in 1968. In fact I was Senior House (Casualty) Officer (A&E or ER) in 1970 at North Manchester General Hospital when I filed the patent. I must have been the only hospital doctor in Britain with an oscilloscope, a soldering iron and a drawing board in his room in the Doctors' Residence. The housekeepers were bemused by all the wires. Frank originally trained as a Banker but quit to take a job with a local electronics firm during the development. He died in 1987, a terrible loss. [Extract from personal communication received in March 2010 from John Kirby.]

Frank and John Kirby and their associate Rodney Lester were pioneers in pharmacy automation and small-object counting technology. In 1967, the Kirbys invented a portable digital tablet counter to count tablets and capsules. With Lester they formed a limited company. In 1970, their invention was patented and put into production in Oldham, England. The tablet counter aided the pharmacy industry with time-consuming manual counting of drug prescriptions.

A counting machine consistently counted medications accurately and quickly. This aspect of pharmacy automation was quickly adopted, and innovations emerged every decade to aid the pharmacy industry to deliver medications quickly, safely, and economically. Modern pharmacies have many new options to improve their workflow by using the new technology, and can choose intelligently from the many options available.[2]

Chronology

On 1 January 1971 commercial production of the first portable digital tablet counters in the World began. John Kirby had filed U.K. Patent number GB1358378(A) on 8 September 1970[3] and U.S. patent number 3789194 on 9 August 1971.[4] These early electronic counters were designed to help pharmacies replace the common (but often inaccurate) practice of counting medications by hand.

In 1975, the digital technology was exported to America. In early 1980 a dedicated research, development and production facility was built in Oldham, England at a cost of £500,000. Between 1982 and 1983, two separate development facilities had been created. In America, overseen by Rodney Lester; and in England, overseen by the Kirby brothers. In 1987, Frank Kirby died. In 1989, John Kirby moved his UK facility to Devon, England.[5]

A simple to operate machine had been developed to accurately and quickly count prescription medications. Technology improvements soon resulted in a more compact model. The price of such equipment in 1980 was around £1,300. This substantial investment in new technology was a major financial consideration, but the pharmacy community considered the use of a counting machine as a superior method compared to hand-counting medications. These early devices became known as tablet counter, capsule counter, pill counter, or drug counter.

The new counting technology replaced manual methods in many industries such as, vitamin and diet supplement manufacturing. Technicians needed a small, affordable device to count and bottle medications. In England and America, the 1980s and 1990s saw new the development of high-speed machines for counting and bottle filling, Like their pharmacy-based counterparts, these industrial units were designed to be fast and simple to operate, yet remain small and cost effective.[6]

In America, in the late 1990s/early 2000s a new type of tablet counter appeared. It was simple to use, compact, inexpensive, and had good counting accuracy. At the turn of the millennium technical advances allowed the design of counters with a software verification system. With an onboard computer, displaying photo images of medications to assist the pharmacist or pharmacy technician to verify that the correct medication was being dispensed. In addition, a database for storing all prescriptions that were counted on the device.[7]

Between September 2005 and May 2007, an American company undertook major financial investment,[8] and relocated. This move added extra space for product research and development facility (R&D). It allowed the opportunity to develop new advanced technology products that met the pharmacy's needs for simple, accurate, and cost-effective ways to dispense prescriptions safely.[9]

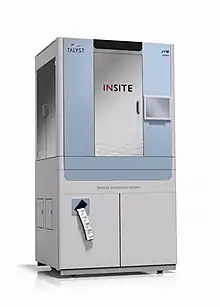

Pictured here is an early American type of integrated counter and packaging device. This machine was a third generation step in the evolution of pharmacy automated devices. Later models held pre-counted containers of commonly-prescribed medications.

Global variations

In the EU member states legislation was introduced in 1998 which had a major effect on UK Pharmacy operations. It effectively prohibited the use of tablet counters for counting and dispensing bulk packaged tablets. Both usage and sales of the machines in the UK declined rapidly as a result of the introduction of blister packaging for medicines.[10]

Current state of the industry

A tablet counter has become a standard in more than 30,000 sites in 35 countries (as of 2010) (including many non-pharmacy sites, such as manufacturing facilities that use a counting machine as a check for small items).[11]

During the 1990s through 2012, numerous new pharmacy automation products came to market. During this timeframe, counting technologies, robotics, workflow management software, and interactive voice recognition (IVR) systems for retail (both chain and independent), outpatient, government, and closed-door pharmacies (mail order and central fill) were all introduced. Additionally, the concept of scalability - of migrating from an entry-level product to the next level of automation (e.g., counting technology to robotics) - was introduced and subsequently launched a new product line in 1997.

Pharmacists everywhere are making the switch to automation for its increased speed, greater accuracy, and better security.[12] As the industry evolves and customer expectations grow, automation is becoming less of a luxury and more of a necessity. Especially for independent pharmacies, automation is now a means of keeping up with the competition of large chain pharmacies.

Technological changes and design improvements

Constant developments in technology make the dispensing of prescription medications safer, more accurate and more efficient.

In America, in 2008, "next-generation" counting and verification systems were introduced. Based on the counting technology employed in preceding models, later machines included the ability to help the pharmacy operate more effectively. Equipped with a new computer interface to a pharmacy management system, with workflow and inventory software. It also included "checks and balances" to ensure the technician and pharmacist were dispensing the correct medication for each patient. This was a step forward to verify all 100% of prescriptions that were dispensed by pharmacy staff.

In America, in 2009, further advanced counters were designed that included the ability to dispense hands-free – a feature that many operators had desired. This allowed pharmacies to automate their most commonly dispensed medications via calibrated cassettes. Thirty of a pharmacy's common medications would now be dispensed automatically. Another new model doubled that throughput via an enclosed robotic mechanism. Robotics had been employed in pharmacies since the mid-1990s, but later machines dispense and label filled patient vials in a comparatively tiny space (about nine square feet of floor space). These newer technologies allowed pharmacy staff to confidently dispense hundreds of prescriptions per day and still be able to manage the many functions of a busy community pharmacy.

Other pharmacy-dispensing concerns besides counting

The primary purpose of a tablet counter (also known as a pill counter or drug counter) is to accurately count prescription medications in tablet or capsule form to aid the requirement for patient medication safety, to increase efficiency and reduce costs for the typical pharmacy. Newer versions of this counting device include advanced software to continue to improve safety for the patient who is receiving the prescription, ensuring that the pharmacy staff dispense the right medication at correct dosage strength for the right patient. (see also medication safety). Today's pharmacy industry recognizes the need for heightened vigilance against medication errors across the entire spectrum. A wealth of research has been conducted regarding the prevalence of medication errors and the ability of technology to decrease or eliminate such errors. (See the March 2003 landmark study by Auburn University's Center for Pharmacy Operations and Designs).[13] Prescription dispensing safety and accuracy in the pharmacy are an essential part of ensuring the right patient gets the right medication at the right dosage. A trend in pharmacy is to place a greater reliance on technology and pharmacy automation to minimize the chance of human error and speed up the process of dispensing. Pharmacy management generally sees technology as a solution to industry challenges like staffing shortages, prescription volume increases, long and hectic work hours and complicated insurance reimbursement procedures. Pharmacies employ advanced technologies that help to handle an ever-escalating number of prescriptions, while making dispensing safer and more precise.

Cross-contamination

Perhaps the most controversial debate surrounding the use of pharmacy automated tablet counters is the impact of cross-contamination. Automated tablet-counting machines (sometimes better known as "pill counters") are designed to sort, count, and dispense drugs at high speeds for quick counting transactions. When more than one drug is exposed to the same surface, leaving seemingly unnoticeable traces of residues, the issue of cross-contamination arises. While one tablet is unlikely to leave enough residues to cause harm to a future patient, the risk of contamination increases sevenfold as the machine processes thousands of varying pills throughout the course of a day. A typical pharmacy may on average process under 100 scripts per day, while other larger dispensaries can accommodate a few hundred scripts in that amount of time.

Thoroughly cleaning pharmacy automated tablet counters is recommended to prevent the chance of cross-contamination. This method is widely preached by manufacturers of these machines, but is not always easily followed. Performing an efficient cleaning of an automated tablet counter significantly increases the amount of time spent on counts by users. Many critics argue that these problems can easily be prevented by taking the proper precautions and following all cleaning procedures, but the increase in time spent makes it hard to justify such an investment. USP<800> Compliance concerning pharmacy automation is an evolving topic.https://www.usp.org/compounding/general-chapter-hazardous-drugs-handling-healthcare The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) considers a drug to be hazardous if it exhibits one or more of the following characteristics in humans or animals: carcinogenicity, teratogenicity or developmental toxicity, reproductive toxicity, organ toxicity at low doses, genotoxicity, or structure and toxicity profiles of new drugs that mimic existing hazardous drugs. Specialty pharmacies that stock and dispense medications on the NIOSH list of Hazardous Drugs must follow strict standards. Community pharmacies typically handle a small number of Hazardous Drugs; therefore, using pharmacy automation for Hazardous Drugs generally follows this guideline: pharmacy staff use an exception tray and spatula to count any Hazardous Drug, and decontaminate the tray and spatula immediately following. Pharmacy robots should not store any Hazardous Drugs for chance of pill-grinding and dust-generation. All other medications dispensed in the pharmacy that are not Hazardous Drugs can be counted with pharmacy automation safely if the manufacturer's cleaning directions are followed.

Future development

Various companies are currently developing a range of remote tablet counters, verification systems and pharmacy automation components to improve the accuracy, safety, speed and efficiency of medication dispensing. Products that are used in retail, mail order, hospital outpatient and specialty pharmacies as well as industrial settings such as manufacturing and component factories. These advanced systems will continue to provide accurate counting without the need for adjustment or calibration when counting in different production environments.

Pictured here is a modern (2010) remote controlled tablet hopper mechanism for use with bulk packaged individual tablets or capsules. In the UK these items are more suited to Hospital Pharmacies, where the issue of E.U. blister packaging regulations relating to medicine packaging does not apply. Also pictured is another version of an automated machine that does not allow unauthorised interference to the internal store of drugs. (A useful security feature in a large pharmacy with public access.)

Repackaging process and stability data

The transient or definitive displacement of the solid oral form from the original atmosphere to enter a repackaging process, sometimes automated, is likely to play a primary role in the pharmaceutical controversy in some countries. However, the solid oral dose is to be repackaged in materials with defined quality. Considering these data, a review of the literature for determination of conditions for repackaged drug stability according to different international guidelines is presented by F Lagrange.[14]

See also

References

- ↑ Melissa Elder (January 2008). "Pharmacy Automation: Technologies and Global Markets BCC00098". Report. Business Communications Company Research. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ↑ Christopher J Thomsen (9 November 2004). "Pharmacy Automation-Practical Technology Solutions for the Pharmacy" (PDF). Business briefing : US Pharmacy review 2004. The Thompson Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ↑ John Kirby Filed 8 September 1970 (3 July 1974). "Patent 1358378". COUNTING MACHINES - Patent GB1358378(A). DTI Data Networks LLC. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ United States Patent Office (29 January 1974). "Patent 3789194". RELATING TO COUNTING MACHINES. Freepatentsonline.com. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ↑ Jordans Business Information Services (2008). "Basic company details for KIRBY DEVON LIMITED". Jordans Ltd. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ Liz Parks (November–December 2003). "Market Survey of Pharmacy Technology and Automation in Retail and Outpatient Pharmacy" (PDF). Retail Pharmacy Management. The Thomsen group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ↑ "An Efficiency Analysis of the Kirby Lester KL16df Automatic Tablet and Capsule Counting System" (PDF). Pharmacy Automation. The ThomsenGroup Inc. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ↑ "American Capital exited its investment in Kirby Lester, LLC in the third quarter of 2007". American Capital Limited. 19 September 2005. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ↑ Kevin Welch (November–December 2009). "Looking Ahead: What's Coming in 2010". Pharmacy Delivery Technology – A Primer. Computer Talk for the Pharmacist. Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ↑ "Labels, patient information leaflets and packaging for medicines". The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 2010. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ↑ Melissa Elder (March 2008). "Pharmacy Automation: Technologies and Global Markets IAS026A". BCC Research. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ↑ Chilcott, Meghann. "The Growing Trend of Pharmacy Automation". Forbes. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ↑ Flynn EA, Barker KN, Carnahan BJ (2003). "National observational study of prescription dispensing accuracy and safety in 50 pharmacies". Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association. 43 (2): 191–200. doi:10.1331/108658003321480731. PMID 12688437.

- ↑ Lagrange F (November 2010). "[Current perspectives on the repackaging and stability of solid oral doses]". Ann Pharm Fr. 68 (6): 332–58. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2010.08.003. PMID 21073993.