Philis de La Charce | |

|---|---|

Statue of Philis de La Charce made in 1900 by Daniel Campagne, now in the Jardin des Dauphins in Grenoble, France. | |

| Born | Philippe de la Tour du Pin de La Charce 5 January 1645 Montmortin, France |

| Died | 4 June 1703 Nyons, France |

| Burial place | Nyons, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Other names | Philis de La Tour |

| Known for | Heroism in battle |

| Parents |

|

Philis de La Charce, also called Philis de La Tour, (5 January 1645 in Montmortin – 4 June 1703 in Nyons) was a French war hero in the Dauphiné region of France during the Nine Years' War, which was waged 1688–1697.

Biography

Her birthname was Philippe de la Tour du Pin de La Charce and she was born in Montmortin as the fifth child of the Protestant noble family La Tour du Pin. The family was particularly influential in the Dauphiné and they lived in the Château de La Charce. Her parents were Catherine Françoise de La Tour du Pin-Mirabel, and Pierre III de la Tour du Pin-Gouvernet, the Margrave of Charce and Lieutenant General or Field Marshal of the King's army of the Dauphiné.[1][2][3][4]

Between 1672 and 1674, Philippe stayed in Nyons, where she met the scholar and poet Antoinette Deshoulières and subsequently, Philippe changed her name to Philis after one of the characters in the novel L'Astrée by Honoré d'Urfé.[1]

When King Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685, which caused an exodus of Protestants from the country, Philis converted to Catholicism and remained in the area.[1]

In 1692, Viktor Amadeus II, Duke of Savoy and King of Sardinia, invaded the Dauphiné to take the French Alpine town of Grenoble. Marshal Nicolas Catinat is credited with thwarting the effort as commander of the French army.[1]

According to legend, Philis de La Charce helped in this action by arming herself with a sword and leading a quickly raised peasant army against the invaders.[5] Other legends attribute several great victories to her, but historians say that she fought only a few local skirmishes.[1][3] Still, it is popularly imagined that she was on horseback with sword in hand when she headed her peasant army to liberate the towns of Gap, the Diois and the Baronnies (which includes Nyon).[6]

Afterward, Philis was called to Paris to "receive the favor of King Louis XIV" for her loyal services.[2]

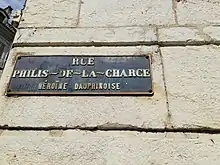

During her stay in Paris, she was awarded a pension by King Louis XIV of 2,000 pounds, a portrait by Pierre Mignard and a dedication by Charles Perrault. A quote by Voltaire, three other portraits, three novels, a statue, a street name in three cities, not to mention the Homeric historical dispute since the end of the 19th century and her systematic presence in local and regional publications at the end of the 20th – beginning 21st centuries show the perpetuation of the legendary gesture of Philis.[2]

Her sword and portrait are kept in the Bourbon crown treasure, and she is sometimes referred to as "the Joan of Arc of Dauphiné."[6]

Philis died in Nyons, where her remains were originally buried in the parish church. In 1857, they were transferred to a mausoleum built for her by the city.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mailhet, André (1909). "LES PROTESTANTS DU DIOIS ET DES BARONNIES EN 1692 PENDANT L'INVASION DU DAUPHINÉ: La Légende de Philis de La Tour La Charce. Sauvetàge d'une statue en détresse". Bulletin de la Société de l'Histoire du Protestantisme Français (1903-). 58 (1): 7–43. ISSN 0037-9050. JSTOR 24287379.

- 1 2 3 "La Motte Chalancon - Philis de la Charce". www.lamottechalancon.com. Retrieved 2021-04-14.

- 1 2 AUED, par (2020-07-08). "Philis de la Charce". Études drômoises (in French). Retrieved 2021-04-14.

- ↑ "Château de La Charce". cartepatrimoine.ladrome.fr (in French). Retrieved 2021-04-14.

- ↑ Du Boys, Albert. Philis de la Charce, ou une héroïne du Dauphiné au XVIIe siècle. France, éditeur non identifié, 1865.

- 1 2 "Statue équestre de Philis de la Charce, 1900, de Daniel CAMPAGNE". www.grenoble-patrimoine.fr (in French). Retrieved 2021-04-14.

External links

- Film in French: MADEMOISELLE DE LA CHARCE (2016)