The Phillips Machine, also known as the MONIAC (Monetary National Income Analogue Computer), Phillips Hydraulic Computer and the Financephalograph, is an analogue computer which uses fluidic logic to model the workings of an economy. The name "MONIAC" is suggested by associating money and ENIAC, an early electronic digital computer.

It was created in 1949 by the New Zealand economist Bill Phillips to model the national economic processes of the United Kingdom, while Phillips was a student at the London School of Economics (LSE). While designed as a teaching tool, it was discovered to be quite accurate, and thus an effective economic simulator.

At least twelve machines were built, donated to or purchased by various organisations around the world. As of 2023, several are in working order.

History

Phillips scrounged materials to create his prototype computer, including bits and pieces of war surplus parts from old Lancaster bombers. The first MONIAC was created in his landlady's garage in Croydon at a cost of £400 (equivalent to £15,000 in 2021).

Phillips first demonstrated the machine to leading economists at the London School of Economics (LSE), of which Phillips was a student, in 1949. It was very well received and Phillips was soon offered a teaching position at the LSE.

The machine had been designed as a teaching aid but was also discovered to be an effective economic simulator.[1] When the machine was created, electronic digital computers that could run complex economic simulations were unavailable. In 1949, the few computers in existence were restricted to government and military use and their lack of adequate visual displays made them unable to illustrate the operation of complex models. Observing the machine in operation made it much easier for students to understand the interrelated processes of a national economy. The range of organisations that acquired a machine showed that it was used in both capacities.

Design

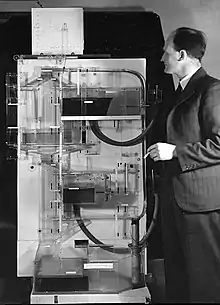

The machine is approximately 2 m (6 ft 7 in) high, 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) wide and almost 1 m (3 ft 3 in) deep, and consisted of a series of transparent plastic tanks and pipes which were fastened to a wooden board. Each tank represented some aspect of the UK national economy and the flow of money around the economy was illustrated by coloured water. At the top of the board was a large tank called the treasury. Water (representing money) flowed from the treasury to other tanks representing the various ways in which a country could spend its money. For example, there were tanks for health and education. To increase spending on health care a tap could be opened to drain water from the treasury to the tank which represented health spending. Water then ran further down the model to other tanks, representing other interactions in the economy. Water could be pumped back to the treasury from some of the tanks to represent taxation. Changes in tax rates were modeled by increasing or decreasing pumping speeds.

Savings reduce the funds available to consumers and investment income increases those funds. The machine showed it by draining water (savings) from the expenditure stream and by injecting water (investment income) into that stream. When the savings flow exceeds the investment flow, the level of water in the savings and investment tank (the surplus-balances tank) would rise to reflect the accumulated balance. When the investment flow exceeds the savings flow for any length of time, the surplus-balances tank would run dry. Import and export were represented by water draining from the model and by additional water being poured into the model.

The flow of the water was automatically controlled through a series of floats, counterweights, electrodes, and cords. When the level of water reached a certain level in a tank, pumps and drains would be activated. To their surprise, Phillips and his associate Walter Newlyn found that machine could be calibrated to an accuracy of 2%.

The flow of water between the tanks was determined by economic principles and the settings for various parameters. Different economic parameters, such as tax rates and investment rates, could be entered by setting the valves which controlled the flow of water about the computer. Users could experiment with different settings and note their effects. The machine's ability to model the subtle interaction of a number of variables made it a powerful tool for its time. When a set of parameters resulted in a viable economy the model would stabilise and the results could be read from scales. The output from the computer could also be sent to a rudimentary plotter.

Locations

It is thought that twelve to fourteen machines were built:

- The prototype was given to the Economics Department at the University of Leeds, where it is on exhibition in the reception of the university's Business School. Copies went to three other British universities.

- Other computers went to the Harvard Business School[2] and Roosevelt College in the United States and Melbourne University in Australia. The Ford Motor Company and the Central Bank of Guatemala are believed to have bought machines.

- A machine owned by Istanbul University is located in the Faculty Of Economics and is available for inspection.

- A machine from the LSE was given to the Science Museum in London and, after conservation, was placed on public display in the museum's mathematics galleries.[3]

- A machine owned by the LSE was donated to the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research in Wellington, New Zealand. This machine formed part of the New Zealand Exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 2003. The machine was set to model the New Zealand economy. In 2007 this machine was restored and placed on permanent display in the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Museum.[4]

- A working machine is at the Faculty of Economics at Cambridge University in the United Kingdom. This machine was restored by Allan McRobie of the Cambridge University Engineering Department, who holds an annual demonstration to students.

- A replica of the machine at the central bank of Guatemala was created for a 2005-6 exhibition entitled "Tropical Economies" at the Wattis Institute of the California College of the Arts in San Francisco.[5]

- The machine at The University of Melbourne, Australia, is on permanent display in the lobby of the Giblin Eunson Library (Ground Floor, Business and Economics Building, 111 Barry st, Carlton, Melbourne). The faculty has sought those interested in restoring the machine.

- Erasmus University Rotterdam (EUR) has owned a machine since 1953. It was a gift from the City of Rotterdam for EUR's 40th anniversary. It is located in the THEIL building.

- Clausthal University of Technology in the faculty of economic sciences.

- Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam had a machine built in 1951 by their instrument makers, modeled after the original. It was called the ECOCIRC (Economic Flow Circulator Demonstrator). It is located on the 8th floor of the Main Building.[6]

Popular culture

The Terry Pratchett novel Making Money contains a similar device as a major plot point. However, after the device is fully perfected, it magically becomes directly coupled to the economy it was intended to simulate, with the result that the machine cannot then be adjusted without causing a change in the actual economy (in parodic resemblance to Goodhart's law).

See also

References

- ↑ Bissell, C. (February 2007). "Historical perspectives — The Moniac A Hydromechanical Analog Computer of the 1950s" (PDF). IEEE Control Systems Magazine. 27 (1): 69–74. doi:10.1109/MCS.2007.284511. S2CID 37510407.

- ↑ "Moniac Machine". New Zealand Institute of Economic Research. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ↑ Phillips, Bill; White Ellerton Limited (1949). "Phillip's Economic Computer". Science Museum Group Collection.

- ↑ "A. W. H.(Bill) Phillips, MBE and the MONIAC" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ↑ "Michael Stevenson: Tropical Economies". Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ↑ "MThe Economic Flow Circulator Demonstrator". Retrieved 22 January 2023.

Further reading

- "The League of Gentlemen". Third Episode of Pandora's Box, a documentary produced by Adam Curtis

- Hally, Mike (2005), Electronic Brains: Stories from the Dawn of the Computer Age, Joseph Henry Press, pp. 187–205, ISBN 0-309-09630-8.

External links

- BBC Radio Four programme 'Water on the brain'.

- NZIER's Moniac Machine

- When Money Flowed Like Water

- Money Flows: Bill Phillips' Financephalograph

- enginuity article

- Swade, Doron (Summer 1995). "The Phillips Economic Computer". Resurrection: The Bulletin of the Computer Conservation Society (12).

- "The Moniac: Economics in thirty fascinating minutes". Fortune. March 1952. pp. 100–1.

- A great disappearing act: the electronic analogue computer

- Catalogue of the AWH Phillips papers at the Archives Division of the London School of Economics.

- Ng, Tim; Wright, Matthew (December 2007). "Introducing the MONIAC: an early and innovative economic model". Reserve Bank of New Zealand Bulletin. 70 (4). Archived from the original on 20 February 2008.

- Video of the Phillips Machine in operation Allan McRobie demonstrates the Phillips Machine at Cambridge University and performs calculations. (A lecture given in 2010).

- McRobie, Allan (2011). "Business Cycles in the Phillips Machine". ASSRU Discussion Papers. Contains detailed diagrams of the Machine workings

- The Phillips Machine Article includes links to videos of the machine in operation.

- Strogatz, Steven (2 June 2009). "Like Water for Money". New York Times.

- LSE Photo of Phillips with the machine

- Bill Phillips Lecture by Alan Bollard, 16 July 2008

- Philips Machine Simulator

- Phillips Economic Model on display in the Science Museum, London

- Istanbul University Moniac Meeting