Philosophical theism is the belief that the Supreme Being exists (or must exist) independent of the teaching or revelation of any particular religion.[1] It represents belief in God entirely without doctrine, except for that which can be discerned by reason and the contemplation of natural laws. Some philosophical theists are persuaded of God's existence by philosophical arguments, while others consider themselves to have a religious faith that need not be, or could not be, supported by rational argument.

Philosophical theism has parallels with the 18th century philosophical view called Deism.

Relationship to organized religion

Philosophical theism conceives of nature as the result of purposive activity and so as an intelligible system open to human understanding, although possibly never completely understandable. It implies the belief that nature is ordered according to some sort of consistent plan and manifests a single purpose or intention, however incomprehensible or inexplicable. However, philosophical theists do not endorse or adhere to the theology or doctrines of any organized religion or church. They may accept arguments or observations about the existence of a god advanced by theologians working in some religious tradition, but reject the tradition itself. (For example, a philosophical theist might believe certain Christian arguments about God while nevertheless rejecting Christianity.)

Notable philosophical theists

- Thales of Miletus (624–546 B.C.) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher and mathematician from Miletus in Asia Minor. Many, most notably Aristotle, regard him as the first philosopher in the Greek tradition. According to Henry Fielding, Diogenes Laërtius affirmed that Thales posed "the independent pre-existence of God from all eternity, stating "that God was the oldest of all beings, for he existed without a previous cause even in the way of generation; that the world was the most beautiful of all things; for it was created by God."[2]

- Socrates (469–399 B.C.) was a classical Greek Athenian philosopher; he is the earliest known proponent of the teleological argument,[3] though it is questionable if he abandoned polytheism.

- Aristotle (384–322 B.C.) founded what are currently known as the "cosmological arguments" for a God (or "first cause").[4]

- Chrysippus of Soli (279–206 B.C.) was a Greek Stoic philosopher. Chrysippus sought to prove the existence of God, making use of a teleological argument: "If there is anything that humanity cannot produce, the being who produces it is better than humanity. But humanity cannot produce the things that are in the universe – the heavenly bodies, etc. The being, therefore, who produces them is superior to humanity. But who is there that is superior to humanity, except God? Therefore, God exists."[5]

- Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 B.C.) was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist.

- Plotinus (204–270 A.D.) was a major philosopher of the ancient world. In his philosophy there are three principles: the One, the Intellect, and the Soul.

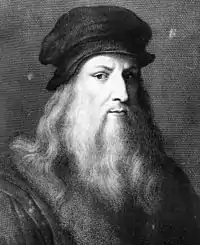

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) was an Italian polymath and is widely considered one of the greatest painters of all time. According to biographer Diane Apostolos-Cappadona, "He found proof for the existence and omnipotence of God in nature—light, color, botany, the human body—and in creativity."[6] Marco Rosci, author of "Hidden Leonardo Da Vinci" (1977) notes that for Leonardo "[m]an is the handiwork of a God who retains few links with traditional orthodoxy. But man is emphatically no mere 'instrument' of his Creator. He is himself a 'machine' of extraordinary quality and proficiency and thus proof of nature's rationality."

- Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695) was a prominent Dutch mathematician and scientist. Huygens was first to formulate what is now known as the second of Newton's laws of motion in a quadratic form. He regarded science as a form of "Worship", that is, one can serve God by studying and admiring his works: "And we shall worship and reverence that God the Maker of all these things; we shall admire and adore his Providence and wonderful Wisdom which is displayed and manifested all over the Universe, to the confusion of those who would have the Earth and all things formed by the shuffling Concourse of Atoms, or to be without beginning."[7]

- Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1726) was an eminent English mathematician, often regarded as one of the three greatest mathematicians who ever lived. Newton was known for his interest in biblical theology and said the following about the scriptures: "We account the Scriptures of God to be the most sublime philosophy. I find more sure marks of authenticity in the Bible than in any profane history whatever." Newton rejected the doctrine of the Trinity and denied recognising the deity of Jesus in his works, which were only found out later by Keynes.[8]

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) was an important German polymath, regarded as the father of digital computing. As a philosopher he argued for the existence of God on purely philosophical grounds. Leibniz wrote: "Even by supposing the world to be eternal, the recourse to an ultimate cause of the universe beyond this world, that is, to God, cannot be avoided."[9]

- Émilie du Châtelet (1706–1749) was a French mathematician, physicist, her most celebrated achievement is considered to be her translation and commentary on Isaac Newton's work Principia Mathematica. In Du Châtelet's words, "[t]he study of nature elevates us to the knowledge of the supreme being; this great truth is even more necessary, if possible, to good physics than to morality, and it ought to be the foundation and conclusion of all the research we make in this science."[10]

- Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) was an American Founding Father who was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence. He argued for God's existence on teleological grounds without appeal to revelation.[11]

- Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) A crucial figure in the transition between the Classical and Romantic eras in Western art music, he remains one of the most famous and influential of all composers. Beethoven never affirmed that he was a Christian later in life, nevertheless he did affirm that "if order and beauty are reflected in the constitution of the universe, then there is a God."[12]

- Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot (1796–1832) was a French military engineer and physicist, often described as the "father of thermodynamics". As a deist, he believed in divine causality, stating that "what to an ignorant man is chance, cannot be chance to one better instructed," but he did not believe in divine punishment. He criticized established religion, though at the same time spoke in favor of "the belief in an all-powerful Being, who loves us and watches over us."[13]

- Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) Sometimes referred to as the "Princeps mathematicorum" (Latin, "the foremost of mathematicians") and "greatest mathematician since antiquity". According to biographer Dunnington, Gauss's religion was based upon the search for truth. He believed in "the immortality of the spiritual individuality, in a personal permanence after death, in a last order of things, in an eternal, righteous, omniscient and omnipotent God".[14]

- Sir Richard Owen (1804–1892) was an English comparative anatomist and paleontologist. He produced a vast array of scientific work, but is probably best remembered today for coining the word Dinosauria (meaning "Terrible Reptile" or "Fearfully Great Reptile"). Owen is also remembered for his outspoken opposition to Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection. He wrote "The satisfaction felt by the rightly constituted mind must ever be great in recognizing the fitness of parts for their appropriate function..the prescient operations of the One Cause of all organization becomes strikingly manifested to our limited intelligence."[15]

- Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865) was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. According to James W. Keyes, "A reason he gave for his belief [in a "Creator of all things"] was, that in view of the Order and harmony of all nature which all beheld, it would have been More miraculous to have Come about by chance, than to have been created and arranged by some great thinking power."[16]

- Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913) was a British naturalist, biologist and co-discoverer of natural selection. Wallace later began to doubt his own theory of natural selection and advocated a teleological form of evolution, in a letter to James Marchant he wrote, "The completely materialistic mind of my youth and early manhood has been slowly molded into the socialistic, spiritualistic, and theistic mind I now exhibit."[17]

- Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914) was an American philosopher, logician, mathematician, and scientist who sketches, for God's reality, an argument to a hypothesis of God as the Necessary Being.[18]

- Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947) was an English mathematician and philosopher who found that following through on the development of an innovative philosophy led to the inclusion of God in the system.

- Henry Truro Bray (1846–1922) was an English-American priest, philosopher and physician who promoted a type of philosophical theism in his book The Living Universe.[19][20]

- John Evan Turner (1875–1947) was a Welsh idealist philosopher known for defending an idealistic theism in his books Personality and Reality (1926) and The Nature of Deity (1927).[21][22]

- A. C. Ewing (1899–1973) was an English philosopher who authored Value and Reality: The Philosophical Case for Theism in 1973.[23][24]

- Kurt Gödel (1906–1978) was the preeminent mathematical logician of the twentieth century who described his theistic belief as independent of theology.[25] He also composed a formal argument for God's existence known as Gödel's ontological proof.

- Martin Gardner (1914–2010) was a mathematics and science writer who defended philosophical theism while denying revelation and the miraculous. Gardner believed that many liberal Protestant preachers, such as Harry Emerson Fosdick and Norman Vincent Peale, were really philosophical theists without admitting (or realizing) the fact.[26]

References

- ↑ Swinburne, Richard (2001). "Philosophical Theism". In D. Z. Phillips; Timothy Tessin (eds.). Philosophy of religion in the 21st century. Claremont studies in the philosophy of religion. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire ; New York: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-333-80175-8.

- ↑ Fielding, Henry. 1775. An essay on conversation. John Bell. p. 346

- ↑ Xenophon, Memorabilia I.4.6; Franklin, James (2001). The Science of Conjecture: Evidence and Probability Before Pascal. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-8018-6569-5.

- ↑ Aristotle's Physics (VIII, 4–6) and Metaphysics (XII, 1–6)

- ↑ Cicero, De Natura Deorum, iii. 10. Cf. ii. 6 for the fuller version of this argument.

- ↑ Apostolos-Cappadona, Diane. "Leonardo: His Faith, His Art." Before 2 Nov. 2009. 26 Jan. 2010.

- ↑ Huygens, Christiaan, Cosmotheoros (1698)

- ↑ Keynes, J.M., 'Newton, The Man'; Proceedings of the Royal Society Newton Tercentenary Celebrations, 15–19 July 1946; Cambridge University Press (1947)

- ↑ Leibniz, G. W. (1697) On the ultimate origination of the universe.

- ↑ Lascano, Marcy P., 2011, “Émilie du Châtelet on the Existence and Nature of God: An Examination of Her Arguments in Light of Their Sources”, British Journal for the History of Philosophy, 19(4): 741–58.

- ↑ To JOHN ADAMS vii 281 1823 Jefferson Cyclopedia, Foley 1900

- ↑ Patrick Kavanaugh, Spiritual Lives of the Great Composers (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, rev. ed. 1996)

- ↑ R. H. Thurston, 1890., Appendix A. pp. 215-217

- ↑ Dunnington, G. Waldo; Gray, Jeremy; Dohse, Fritz-Egbert (2004). Carl Friedrich Gauss: titan of science. Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-547-8. p. 305.

- ↑ Owen, On the Nature of Limbs, 38.

- ↑ 352. James W. Keyes (statement for Willam H. Herndon).[1865 — 66]

- ↑ When I was alive by Alfred Russel Wallace, THE LINNEAN 1995 VOLUME 11(2), pp. 9

- ↑ Peirce (1908), "A Neglected Argument for the Reality of God", published in large part, Hibbert Journal v. 7, 90–112. Reprinted with an unpublished part, CP 6.452–85, Selected Writings pp. 358–79, EP 2:434–50, Peirce on Signs 260–78.

- ↑ The Living Universe. The New York Times Saturday Review of Books and Art (July, 1910). p. 386

- ↑ "The Living Universe". The Twentieth Century Magazine (October, 1910). Volume 3. p. 186

- ↑ Mackenzie, J. S. (1926). "Personality and Reality: A Proof of the Reality of a Supreme Self in the Universe By J. E. Turner". Philosophy. 1 (4): 516–517.

- ↑ Burgh, W. G. de. (1927). "Reviewed Work: The Nature of Deity: A Sequel to "Personality and Reality" by J. E. Turner". Journal of Philosophical Studies. 2 (7): 392–395.

- ↑ McPherson, Thomas (1975). "Reviewed Work: Value and Reality, The Philosophical Case for Theism. by A. C. Ewing". Mind. 84 (336): 625–628.

- ↑ Tooley, Michael (1976). "Reviewed Work: Value and Reality: The Philosophical Case for Theism by A. C. Ewing". The Philosophical Review. 85 (1): 115–121.

- ↑ Wang 1996, pp. 104–105.

- ↑ According to Gardner: "I am a philosophical theist. I believe in a personal god, and I believe in an afterlife, and I believe in prayer, but I don’t believe in any established religion. This is called philosophical theism.... Philosophical theism is entirely emotional. As Kant said, he destroyed pure reason to make room for faith." Carpenter, Alexander (2008), "Martin Gardner on Philosophical Theism, Adventists and Price" Interview, 17 October 2008, Spectrum.