Forms of phosphorus Waxy white Light red Dark red and violet Black | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phosphorus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈfɒsfərəs/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allotropes | white, red, violet, black and others (see Allotropes of phosphorus) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | white, red and violet are waxy, black is metallic-looking | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(P) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abundance | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| in the Earth's crust | 5.2 (silicon = 100) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phosphorus in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 15 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 15 (pnictogens) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ne] 3s2 3p3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | white: 317.3 K (44.15 °C, 111.5 °F) red: ∼860 K (∼590 °C, ∼1090 °F)[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | white: 553.7 K (280.5 °C, 536.9 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sublimation point | red: ≈689.2–863 K (≈416–590 °C, ≈780.8–1094 °F) violet: 893 K (620 °C, 1148 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | white: 1.823 g/cm3 red: ≈2.2–2.34 g/cm3 violet: 2.36 g/cm3 black: 2.69 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | white: 0.66 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporisation | white: 51.9 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | white: 23.824 J/(mol·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapour pressure (white)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapour pressure (red)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −3, −2, −1, 0,[3] +1,[4] +2, +3, +4, +5 (a mildly acidic oxide) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.19 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionisation energies |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 107±3 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 180 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

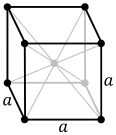

| Crystal structure | body-centred cubic (bcc) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | white: 0.236 W/(m⋅K) black: 12.1 W/(m⋅K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | white, red, violet, black: diamagnetic[5] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | −20.8×10−6 cm3/mol (293 K)[6] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | white: 5 GPa red: 11 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7723-14-0 (red) 12185-10-3 (white) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Hennig Brand (1669) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recognised as an element by | Antoine Lavoisier[7] (1777) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of phosphorus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Phosphorus is a chemical element; it has symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Earth. It has a concentration in the Earth's crust of about one gram per kilogram (compare copper at about 0.06 grams). In minerals, phosphorus generally occurs as phosphate.

Elemental phosphorus was first isolated as white phosphorus in 1669. In white phosphorus, phosphorus atoms are arranged in groups of 4, written as P4. White phosphorus emits a faint glow when exposed to oxygen – hence the name, taken from Greek mythology, Φωσφόρος meaning 'light-bearer' (Latin Lucifer), referring to the "Morning Star", the planet Venus. The term phosphorescence, meaning glow after illumination, derives from this property of phosphorus, although the word has since been used for a different physical process that produces a glow. The glow of phosphorus is caused by oxidation of the white (but not red) phosphorus — a process now called chemiluminescence. Phosphorus is classified as a pnictogen, together with nitrogen, arsenic, antimony, bismuth, and moscovium.

Phosphorus is an element essential to sustaining life largely through phosphates, compounds containing the phosphate ion, PO43−. Phosphates are a component of DNA, RNA, ATP, and phospholipids, complex compounds fundamental to cells. Elemental phosphorus was first isolated from human urine, and bone ash was an important early phosphate source. Phosphate mines contain fossils because phosphate is present in the fossilized deposits of animal remains and excreta. Low phosphate levels are an important limit to growth in a number of plant ecosystems. The vast majority of phosphorus compounds mined are consumed as fertilisers. Phosphate is needed to replace the phosphorus that plants remove from the soil, and its annual demand is rising nearly twice as fast as the growth of the human population. Other applications include organophosphorus compounds in detergents, pesticides, and nerve agents.

Characteristics

Allotropes

Phosphorus has several allotropes that exhibit strikingly diverse properties.[8] The two most common allotropes are white phosphorus and red phosphorus.[9]

From the perspective of applications and chemical literature, the most important form of elemental phosphorus is white phosphorus, often abbreviated as WP. It is a soft, waxy solid which consists of tetrahedral P

4 molecules, in which each atom is bound to the other three atoms by a formal single bond. This P

4 tetrahedron is also present in liquid and gaseous phosphorus up to the temperature of 800 °C (1,470 °F) when it starts decomposing to P

2 molecules.[10] The P

4 molecule in the gas phase has a P-P bond length of rg = 2.1994(3) Å as was determined by gas electron diffraction.[11] The nature of bonding in this P

4 tetrahedron can be described by spherical aromaticity or cluster bonding, that is the electrons are highly delocalized. This has been illustrated by calculations of the magnetically induced currents, which sum up to 29 nA/T, much more than in the archetypical aromatic molecule benzene (11 nA/T).[11]

White phosphorus exists in two crystalline forms: α (alpha) and β (beta). At room temperature, the α-form is stable. It is more common, has cubic crystal structure and at 195.2 K (−78.0 °C), it transforms into β-form, which has hexagonal crystal structure. These forms differ in terms of the relative orientations of the constituent P4 tetrahedra.[12][13] The β form of white phosphorus contains three slightly different P

4 molecules, i.e. 18 different P-P bond lengths between 2.1768(5) and 2.1920(5) Å. The average P-P bond length is 2.183(5) Å.[14]

White phosphorus is the least stable, the most reactive, the most volatile, the least dense and the most toxic of the allotropes. White phosphorus gradually changes to red phosphorus. This transformation is accelerated by light and heat, and samples of white phosphorus almost always contain some red phosphorus and accordingly appear yellow. For this reason, white phosphorus that is aged or otherwise impure (e.g., weapons-grade, not lab-grade WP) is also called yellow phosphorus. When exposed to oxygen, white phosphorus glows in the dark with a very faint tinge of green and blue. It is highly flammable and pyrophoric (self-igniting) upon contact with air. Owing to its pyrophoricity, white phosphorus is used as an additive in napalm. The odour of combustion of this form has a characteristic garlic smell, and samples are commonly coated with white phosphorus pentoxide, which consists of P

4O

10 tetrahedra with oxygen inserted between the phosphorus atoms and at their vertices. White phosphorus is insoluble in water but soluble in carbon disulfide.[15]

Thermal decomposition of P4 at 1100 K gives diphosphorus, P2. This species is not stable as a solid or liquid. The dimeric unit contains a triple bond and is analogous to N2. It can also be generated as a transient intermediate in solution by thermolysis of organophosphorus precursor reagents.[16] At still higher temperatures, P2 dissociates into atomic P.[15]

| Form | white(α) | white(β) | red | violet | black |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry | Body-centred cubic |

Triclinic | Amorphous | Monoclinic | Orthorhombic |

| Pearson symbol | aP24 | mP84 | oS8 | ||

| Space group | I43m | P1 No.2 | P2/c No.13 | Cmce No.64 | |

| Density (g/cm3) | 1.828 | 1.88 | ~2.2 | 2.36 | 2.69 |

| Band gap (eV) | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 0.34 | |

| Refractive index | 1.8244 | 2.6 | 2.4 |

Red phosphorus is polymeric in structure. It can be viewed as a derivative of P4 wherein one P-P bond is broken, and one additional bond is formed with the neighbouring tetrahedron resulting in chains of P21 molecules linked by van der Waals forces.[18] Red phosphorus may be formed by heating white phosphorus to 250 °C (482 °F) or by exposing white phosphorus to sunlight.[19] Phosphorus after this treatment is amorphous. Upon further heating, this material crystallises. In this sense, red phosphorus is not an allotrope, but rather an intermediate phase between the white and violet phosphorus, and most of its properties have a range of values. For example, freshly prepared, bright red phosphorus is highly reactive and ignites at about 300 °C (572 °F),[20] though it is more stable than white phosphorus, which ignites at about 30 °C (86 °F).[21] After prolonged heating or storage, the color darkens (see infobox images); the resulting product is more stable and does not spontaneously ignite in air.[22]

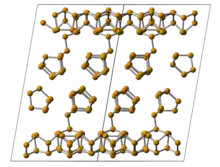

Violet phosphorus is a form of phosphorus that can be produced by day-long annealing of red phosphorus above 550 °C. In 1865, Hittorf discovered that when phosphorus was recrystallised from molten lead, a red/purple form is obtained. Therefore, this form is sometimes known as "Hittorf's phosphorus" (or violet or α-metallic phosphorus).[17]

Black phosphorus is the least reactive allotrope and the thermodynamically stable form below 550 °C (1,022 °F). It is also known as β-metallic phosphorus and has a structure somewhat resembling that of graphite.[23][24] It is obtained by heating white phosphorus under high pressures (about 12,000 standard atmospheres or 1.2 gigapascals). It can also be produced at ambient conditions using metal salts, e.g. mercury, as catalysts.[25] In appearance, properties, and structure, it resembles graphite, being black and flaky, a conductor of electricity, and has puckered sheets of linked atoms.[26]

Another form, scarlet phosphorus, is obtained by allowing a solution of white phosphorus in carbon disulfide to evaporate in sunlight.[17]

Chemiluminescence

When first isolated, it was observed that the green glow emanating from white phosphorus would persist for a time in a stoppered jar, but then cease. Robert Boyle in the 1680s ascribed it to "debilitation" of the air. Actually, it is oxygen being consumed. By the 18th century, it was known that in pure oxygen, phosphorus does not glow at all;[27] there is only a range of partial pressures at which it does. Heat can be applied to drive the reaction at higher pressures.[28]

In 1974, the glow was explained by R. J. van Zee and A. U. Khan.[29][30] A reaction with oxygen takes place at the surface of the solid (or liquid) phosphorus, forming the short-lived molecules HPO and P

2O

2 that both emit visible light. The reaction is slow and only very little of the intermediates are required to produce the luminescence, hence the extended time the glow continues in a stoppered jar.

Since its discovery, phosphors and phosphorescence were used loosely to describe substances that shine in the dark without burning. Although the term phosphorescence is derived from phosphorus, the reaction that gives phosphorus its glow is properly called chemiluminescence (glowing due to a cold chemical reaction), not phosphorescence (re-emitting light that previously fell onto a substance and excited it).[31]

Isotopes

There are 22 known isotopes of phosphorus,[32] ranging from 26

P to 47

P.[33] Only 31

P is stable and is therefore present at 100% abundance. The half-integer nuclear spin and high abundance of 31P make phosphorus-31 NMR spectroscopy a very useful analytical tool in studies of phosphorus-containing samples.

Two radioactive isotopes of phosphorus have half-lives suitable for biological scientific experiments. These are:

- 32

P, a beta-emitter (1.71 MeV) with a half-life of 14.3 days, which is used routinely in life-science laboratories, primarily to produce radiolabeled DNA and RNA probes, e.g. for use in Northern blots or Southern blots. - 33

P, a beta-emitter (0.25 MeV) with a half-life of 25.4 days. It is used in life-science laboratories in applications in which lower energy beta emissions are advantageous such as DNA sequencing.

The high-energy beta particles from 32

P penetrate skin and corneas and any 32

P ingested, inhaled, or absorbed is readily incorporated into bone and nucleic acids. For these reasons, Occupational Safety and Health Administration in the United States, and similar institutions in other developed countries require personnel working with 32

P to wear lab coats, disposable gloves, and safety glasses or goggles to protect the eyes, and avoid working directly over open containers. Monitoring personal, clothing, and surface contamination is also required. Shielding requires special consideration. The high energy of the beta particles gives rise to secondary emission of X-rays via Bremsstrahlung (braking radiation) in dense shielding materials such as lead. Therefore, the radiation must be shielded with low density materials such as acrylic or other plastic, water, or (when transparency is not required), even wood.[34]

Occurrence

Universe

In 2013, astronomers detected phosphorus in Cassiopeia A, which confirmed that this element is produced in supernovae as a byproduct of supernova nucleosynthesis. The phosphorus-to-iron ratio in material from the supernova remnant could be up to 100 times higher than in the Milky Way in general.[35]

In 2020, astronomers analysed ALMA and ROSINA data from the massive star-forming region AFGL 5142, to detect phosphorus-bearing molecules and how they are carried in comets to the early Earth.[36][37]

Crust and organic sources

Phosphorus has a concentration in the Earth's crust of about one gram per kilogram (compare copper at about 0.06 grams). It is not found free in nature, but is widely distributed in many minerals, usually as phosphates.[9] Inorganic phosphate rock, which is partially made of apatite (a group of minerals being, generally, pentacalcium triorthophosphate fluoride (hydroxide)), is today the chief commercial source of this element. According to the US Geological Survey (USGS), about 50 percent of the global phosphorus reserves are in Amazigh nations like Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia.[38] 85% of Earth's known reserves are in Morocco with smaller deposits in China, Russia,[39] Florida, Idaho, Tennessee, Utah, and elsewhere.[40] Albright and Wilson in the UK and their Niagara Falls plant, for instance, were using phosphate rock in the 1890s and 1900s from Tennessee, Florida, and the Îles du Connétable (guano island sources of phosphate); by 1950, they were using phosphate rock mainly from Tennessee and North Africa.[41]

Organic sources, namely urine, bone ash and (in the latter 19th century) guano, were historically of importance but had only limited commercial success.[42] As urine contains phosphorus, it has fertilising qualities which are still harnessed today in some countries, including Sweden, using methods for reuse of excreta. To this end, urine can be used as a fertiliser in its pure form or part of being mixed with water in the form of sewage or sewage sludge.

Compounds

Phosphorus(V)

The most prevalent compounds of phosphorus are derivatives of phosphate (PO43−), a tetrahedral anion.[43] Phosphate is the conjugate base of phosphoric acid, which is produced on a massive scale for use in fertilisers. Being triprotic, phosphoric acid converts stepwise to three conjugate bases:

- H3PO4 + H2O ⇌ H3O+ + H2PO4− Ka1 = 7.25×10−3

- H2PO4− + H2O ⇌ H3O+ + HPO42− Ka2 = 6.31×10−8

- HPO42− + H2O ⇌ H3O+ + PO43− Ka3 = 3.98×10−13

Phosphate exhibits a tendency to form chains and rings containing P-O-P bonds. Many polyphosphates are known, including ATP. Polyphosphates arise by dehydration of hydrogen phosphates such as HPO42− and H2PO4−. For example, the industrially important pentasodium triphosphate (also known as sodium tripolyphosphate, STPP) is produced industrially by the megatonne by this condensation reaction:

- 2 Na2HPO4 + NaH2PO4 → Na5P3O10 + 2 H2O

Phosphorus pentoxide (P4O10) is the acid anhydride of phosphoric acid, but several intermediates between the two are known. This waxy white solid reacts vigorously with water.

With metal cations, phosphate forms a variety of salts. These solids are polymeric, featuring P-O-M linkages. When the metal cation has a charge of 2+ or 3+, the salts are generally insoluble, hence they exist as common minerals. Many phosphate salts are derived from hydrogen phosphate (HPO42−).

PCl5 and PF5 are common compounds. PF5 is a colourless gas and the molecules have trigonal bipyramidal geometry. PCl5 is a colourless solid which has an ionic formulation of PCl4+ PCl6−, but adopts the trigonal bipyramidal geometry when molten or in the vapour phase.[15] PBr5 is an unstable solid formulated as PBr4+Br−and PI5 is not known.[15] The pentachloride and pentafluoride are Lewis acids. With fluoride, PF5 forms PF6−, an anion that is isoelectronic with SF6. The most important oxyhalide is phosphorus oxychloride, (POCl3), which is approximately tetrahedral.

Before extensive computer calculations were feasible, it was thought that bonding in phosphorus(V) compounds involved d orbitals. Computer modeling of molecular orbital theory indicates that this bonding involves only s- and p-orbitals.[44]

Phosphorus(III)

All four symmetrical trihalides are well known: gaseous PF3, the yellowish liquids PCl3 and PBr3, and the solid PI3. These materials are moisture sensitive, hydrolysing to give phosphorous acid. The trichloride, a common reagent, is produced by chlorination of white phosphorus:

- P4 + 6 Cl2 → 4 PCl3

The trifluoride is produced from the trichloride by halide exchange. PF3 is toxic because it binds to haemoglobin.

Phosphorus(III) oxide, P4O6 (also called tetraphosphorus hexoxide) is the anhydride of P(OH)3, the minor tautomer of phosphorous acid. The structure of P4O6 is like that of P4O10 without the terminal oxide groups.

Phosphorus(I) and phosphorus(II)

These compounds generally feature P–P bonds.[15] Examples include catenated derivatives of phosphine and organophosphines. Compounds containing P=P double bonds have also been observed, although they are rare.

Phosphides and phosphines

Phosphides arise by reaction of metals with red phosphorus. The alkali metals (group 1) and alkaline earth metals can form ionic compounds containing the phosphide ion, P3−. These compounds react with water to form phosphine. Other phosphides, for example Na3P7, are known for these reactive metals. With the transition metals as well as the monophosphides there are metal-rich phosphides, which are generally hard refractory compounds with a metallic lustre, and phosphorus-rich phosphides which are less stable and include semiconductors.[15] Schreibersite is a naturally occurring metal-rich phosphide found in meteorites. The structures of the metal-rich and phosphorus-rich phosphides can be complex.

Phosphine (PH3) and its organic derivatives (PR3) are structural analogues of ammonia (NH3), but the bond angles at phosphorus are closer to 90° for phosphine and its organic derivatives. Phosphine is an ill-smelling, toxic gas. Phosphorus has an oxidation number of −3 in phosphine. Phosphine is produced by hydrolysis of calcium phosphide, Ca3P2. Unlike ammonia, phosphine is oxidised by air. Phosphine is also far less basic than ammonia. Other phosphines are known which contain chains of up to nine phosphorus atoms and have the formula PnHn+2.[15] The highly flammable gas diphosphine (P2H4) is an analogue of hydrazine.

Oxoacids

Phosphorus oxoacids are extensive, often commercially important, and sometimes structurally complicated. They all have acidic protons bound to oxygen atoms, some have nonacidic protons that are bonded directly to phosphorus and some contain phosphorus–phosphorus bonds.[15] Although many oxoacids of phosphorus are formed, only nine are commercially important, and three of them, hypophosphorous acid, phosphorous acid, and phosphoric acid, are particularly important.

| Oxidation state | Formula | Name | Acidic protons | Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +1 | HH2PO2 | hypophosphorous acid | 1 | acid, salts |

| +3 | H3PO3 | phosphorous acid (phosphonic acid) | 2 | acid, salts |

| +3 | HPO2 | metaphosphorous acid | 1 | salts |

| +4 | H4P2O6 | hypophosphoric acid | 4 | acid, salts |

| +5 | (HPO3)n | metaphosphoric acids | n | salts (n = 3,4,6) |

| +5 | H(HPO3)nOH | polyphosphoric acids | n+2 | acids, salts (n = 1-6) |

| +5 | H5P3O10 | tripolyphosphoric acid | 3 | salts |

| +5 | H4P2O7 | pyrophosphoric acid | 4 | acid, salts |

| +5 | H3PO4 | (ortho)phosphoric acid | 3 | acid, salts |

Nitrides

The PN molecule is considered unstable, but is a product of crystalline phosphorus nitride decomposition at 1100 K. Similarly, H2PN is considered unstable, and phosphorus nitride halogens like F2PN, Cl2PN, Br2PN, and I2PN oligomerise into cyclic polyphosphazenes. For example, compounds of the formula (PNCl2)n exist mainly as rings such as the trimer hexachlorophosphazene. The phosphazenes arise by treatment of phosphorus pentachloride with ammonium chloride:

PCl5 + NH4Cl → 1/n (NPCl2)n + 4 HCl

When the chloride groups are replaced by alkoxide (RO−), a family of polymers is produced with potentially useful properties.[45]

Sulfides

Phosphorus forms a wide range of sulfides, where the phosphorus can be in P(V), P(III) or other oxidation states. The three-fold symmetric P4S3 is used in strike-anywhere matches. P4S10 and P4O10 have analogous structures.[46] Mixed oxyhalides and oxyhydrides of phosphorus(III) are almost unknown.

Organophosphorus compounds

Compounds with P-C and P-O-C bonds are often classified as organophosphorus compounds. They are widely used commercially. The PCl3 serves as a source of P3+ in routes to organophosphorus(III) compounds. For example, it is the precursor to triphenylphosphine:

- PCl3 + 6 Na + 3 C6H5Cl → P(C6H5)3 + 6 NaCl

Treatment of phosphorus trihalides with alcohols and phenols gives phosphites, e.g. triphenylphosphite:

- PCl3 + 3 C6H5OH → P(OC6H5)3 + 3 HCl

Similar reactions occur for phosphorus oxychloride, affording triphenylphosphate:

- OPCl3 + 3 C6H5OH → OP(OC6H5)3 + 3 HCl

History

Etymology

The name Phosphorus in Ancient Greece was the name for the planet Venus and is derived from the Greek words (φῶς = light, φέρω = carry), which roughly translates as light-bringer or light carrier.[19] (In Greek mythology and tradition, Augerinus (Αυγερινός = morning star, still in use today), Hesperus or Hesperinus (΄Εσπερος or Εσπερινός or Αποσπερίτης = evening star, still in use today) and Eosphorus (Εωσφόρος = dawnbearer, not in use for the planet after Christianity) are close homologues, and also associated with Phosphorus-the-morning-star).

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the correct spelling of the element is phosphorus. The word phosphorous is the adjectival form of the P3+ valence: so, just as sulfur forms sulfurous and sulfuric compounds, phosphorus forms phosphorous compounds (e.g., phosphorous acid) and P5+ valence phosphoric compounds (e.g., phosphoric acids and phosphates).

Discovery

The discovery of phosphorus, the first element to be discovered that was not known since ancient times,[47] is credited to the German alchemist Hennig Brand in 1669, although others might have discovered phosphorus around the same time.[48] Brand experimented with urine, which contains considerable quantities of dissolved phosphates from normal metabolism.[19] Working in Hamburg, Brand attempted to create the fabled philosopher's stone through the distillation of some salts by evaporating urine, and in the process produced a white material that glowed in the dark and burned brilliantly. It was named phosphorus mirabilis ("miraculous bearer of light").[49]

Brand's process originally involved letting urine stand for days until it gave off a terrible smell. Then he boiled it down to a paste, heated this paste to a high temperature, and led the vapours through water, where he hoped they would condense to gold. Instead, he obtained a white, waxy substance that glowed in the dark. Brand had discovered phosphorus. Specifically, Brand produced ammonium sodium hydrogen phosphate, (NH

4)NaHPO

4. While the quantities were essentially correct (it took about 1,100 litres [290 US gal] of urine to make about 60 g of phosphorus), it was unnecessary to allow the urine to rot first. Later scientists discovered that fresh urine yielded the same amount of phosphorus.[31]

Brand at first tried to keep the method secret,[50] but later sold the recipe for 200 thalers to Johann Daniel Kraft (de) from Dresden.[19] Krafft toured much of Europe with it, including England, where he met with Robert Boyle. The secret—that the substance was made from urine—leaked out, and Johann Kunckel (1630–1703) was able to reproduce it in Sweden (1678). Later, Boyle in London (1680) also managed to make phosphorus, possibly with the aid of his assistant, Ambrose Godfrey-Hanckwitz. Godfrey later made a business of the manufacture of phosphorus.

Boyle states that Krafft gave him no information as to the preparation of phosphorus other than that it was derived from "somewhat that belonged to the body of man". This gave Boyle a valuable clue, so that he, too, managed to make phosphorus, and published the method of its manufacture.[19] Later he improved Brand's process by using sand in the reaction (still using urine as base material),

- 4 NaPO

3 + 2 SiO

2 + 10 C → 2 Na

2SiO

3 + 10 CO + P

4

Robert Boyle was the first to use phosphorus to ignite sulfur-tipped wooden splints, forerunners of our modern matches, in 1680.[51]

Phosphorus was the 13th element to be discovered. Because of its tendency to spontaneously combust when left alone in air, it is sometimes referred to as "the Devil's element".[52]

Bone ash and guano

Antoine Lavoisier recognized phosphorus as an element in 1777 after Johan Gottlieb Gahn and Carl Wilhelm Scheele, in 1769, showed that calcium phosphate (Ca

3(PO

4)

2) is found in bones by obtaining elemental phosphorus from bone ash.[53]

Bone ash was the major source of phosphorus until the 1840s. The method started by roasting bones, then employed the use of fire clay retorts encased in a very hot brick furnace to distill out the highly toxic elemental phosphorus product.[54] Alternately, precipitated phosphates could be made from ground-up bones that had been de-greased and treated with strong acids. White phosphorus could then be made by heating the precipitated phosphates, mixed with ground coal or charcoal in an iron pot, and distilling off phosphorus vapour in a retort.[55] Carbon monoxide and other flammable gases produced during the reduction process were burnt off in a flare stack.

In the 1840s, world phosphate production turned to the mining of tropical island deposits formed from bird and bat guano (see also Guano Islands Act). These became an important source of phosphates for fertiliser in the latter half of the 19th century.[56]

Phosphate rock

Phosphate rock, which usually contains calcium phosphate, was first used in 1850 to make phosphorus, and following the introduction of the electric arc furnace by James Burgess Readman in 1888[57] (patented 1889),[58] elemental phosphorus production switched from the bone-ash heating, to electric arc production from phosphate rock. After the depletion of world guano sources about the same time, mineral phosphates became the major source of phosphate fertiliser production. Phosphate rock production greatly increased after World War II, and remains the primary global source of phosphorus and phosphorus chemicals today. See the article on peak phosphorus for more information on the history and present state of phosphate mining. Phosphate rock remains a feedstock in the fertiliser industry, where it is treated with sulfuric acid to produce various "superphosphate" fertiliser products.

Incendiaries

White phosphorus was first made commercially in the 19th century for the match industry. This used bone ash for a phosphate source, as described above. The bone-ash process became obsolete when the submerged-arc furnace for phosphorus production was introduced to reduce phosphate rock.[59][60] The electric furnace method allowed production to increase to the point where phosphorus could be used in weapons of war.[29][61] In World War I, it was used in incendiaries, smoke screens and tracer bullets.[61] A special incendiary bullet was developed to shoot at hydrogen-filled Zeppelins over Britain (hydrogen being highly flammable).[61] During World War II, Molotov cocktails made of phosphorus dissolved in petrol were distributed in Britain to specially selected civilians within the British resistance operation, for defence; and phosphorus incendiary bombs were used in war on a large scale. Burning phosphorus is difficult to extinguish and if it splashes onto human skin it has horrific effects.[15]

Early matches used white phosphorus in their composition, which was dangerous due to its toxicity. Murders, suicides and accidental poisonings resulted from its use. (An apocryphal tale tells of a woman attempting to murder her husband with white phosphorus in his food, which was detected by the stew's giving off luminous steam).[29] In addition, exposure to the vapours gave match workers a severe necrosis of the bones of the jaw, known as "phossy jaw". When a safe process for manufacturing red phosphorus was discovered, with its far lower flammability and toxicity, laws were enacted, under the Berne Convention (1906), requiring its adoption as a safer alternative for match manufacture.[62] The toxicity of white phosphorus led to discontinuation of its use in matches.[63] The Allies used phosphorus incendiary bombs in World War II to destroy Hamburg, the place where the "miraculous bearer of light" was first discovered.[49]

Production

.jpg.webp)

In 2017, the USGS estimated 68 billion tons of world reserves, where reserve figures refer to the amount assumed recoverable at current market prices; 0.261 billion tons were mined in 2016.[64] Critical to contemporary agriculture, its annual demand is rising nearly twice as fast as the growth of the human population.[39] The production of phosphorus may have peaked before 2011 and some scientists predict reserves will be depleted before the end of the 21st century.[65][39][66] Phosphorus comprises about 0.1% by mass of the average rock, and consequently, the Earth's supply is vast, though dilute.[15]

Wet process

Most phosphorus-bearing material is for agriculture fertilisers. In this case where the standards of purity are modest, phosphorus is obtained from phosphate rock by what is called the "wet process." The minerals are treated with sulfuric acid to give phosphoric acid. Phosphoric acid is then neutralized to give various phosphate salts, which comprise fertilizers. In the wet process, phosphorus does not undergo redox.[67] About five tons of phosphogypsum waste are generated per ton of phosphoric acid production. Annually, the estimated generation of phosphogypsum worldwide is 100 to 280 Mt.[68]

Thermal process

For the use of phosphorus in drugs, detergents, and foodstuff, the standards of purity are high, which led to the development of the thermal process. In this process, phosphate minerals are converted to white phosphorus, which can be purified by distillation. The white phosphorus is then oxidised to phosphoric acid and subsequently neutralised with a base to give phosphate salts. The thermal process is conducted in a submerged-arc furnace which is energy intensive.[67] Presently, about 1,000,000 short tons (910,000 t) of elemental phosphorus is produced annually. Calcium phosphate (as phosphate rock), mostly mined in Florida and North Africa, can be heated to 1,200–1,500 °C with sand, which is mostly SiO

2, and coke to produce P

4. The P

4 product, being volatile, is readily isolated:[69]

- 4 Ca5(PO4)3F + 18 SiO2 + 30 C → 3 P4 + 30 CO + 18 CaSiO3 + 2 CaF2

- 2 Ca3(PO4)2 + 6 SiO2 + 10 C → 6 CaSiO3 + 10 CO + P4

Side products from the thermal process include ferrophosphorus, a crude form of Fe2P, resulting from iron impurities in the mineral precursors. The silicate slag is a useful construction material. The fluoride is sometimes recovered for use in water fluoridation. More problematic is a "mud" containing significant amounts of white phosphorus. Production of white phosphorus is conducted in large facilities in part because it is energy intensive. The white phosphorus is transported in molten form. Some major accidents have occurred during transportation.[70]

Historical routes

Historically, before the development of mineral-based extractions, white phosphorus was isolated on an industrial scale from bone ash.[71] In this process, the tricalcium phosphate in bone ash is converted to monocalcium phosphate with sulfuric acid:

- Ca3(PO4)2 + 2 H2SO4 → Ca(H2PO4)2 + 2 CaSO4

Monocalcium phosphate is then dehydrated to the corresponding metaphosphate:

- Ca(H2PO4)2 → Ca(PO3)2 + 2 H2O

When ignited to a white heat (~1300 °C) with charcoal, calcium metaphosphate yields two-thirds of its weight of white phosphorus while one-third of the phosphorus remains in the residue as calcium orthophosphate:

- 3 Ca(PO3)2 + 10 C → Ca3(PO4)2 + 10 CO + P4

Applications

Flame retardant

Phosphorus compounds are used as flame retardants. Flame-retardant materials and coatings are being developed that are both phosphorus- and bio-based.[72]

Food additive

Phosphorus is an essential mineral for humans listed in the Dietary Reference Intake (DRI).

Food-grade phosphoric acid (additive E338[73]) is used to acidify foods and beverages such as various colas and jams, providing a tangy or sour taste. The phosphoric acid also serves as a preservative.[74] Soft drinks containing phosphoric acid, which would include Coca-Cola, are sometimes called phosphate sodas or phosphates. Phosphoric acid in soft drinks has the potential to cause dental erosion.[75] Phosphoric acid also has the potential to contribute to the formation of kidney stones, especially in those who have had kidney stones previously.[76]

Fertiliser

Phosphorus is an essential plant nutrient (the most often limiting nutrient, after nitrogen),[77] and the bulk of all phosphorus production is in concentrated phosphoric acids for agriculture fertilisers, containing as much as 70% to 75% P2O5. That led to large increase in phosphate (PO43−) production in the second half of the 20th century.[39] Artificial phosphate fertilisation is necessary because phosphorus is essential to all living organisms; it is involved in energy transfers, strength of root and stems, photosynthesis, the expansion of plant roots, formation of seeds and flowers, and other important factors effecting overall plant health and genetics.[77] Heavy use of phosphorus fertilizers and their runoff have resulted in eutrophication (overenrichment) of aquatic ecosystems.[78][79]

Natural phosphorus-bearing compounds are mostly inaccessible to plants because of the low solubility and mobility in soil.[80] Most phosphorus is very stable in the soil minerals or organic matter of the soil. Even when phosphorus is added in manure or fertilizer it can become fixed in the soil. Therefore, the natural phosphorus cycle is very slow. Some of the fixed phosphorus is released again over time, sustaining wild plant growth, however, more is needed to sustain intensive cultivation of crops.[81] Fertiliser is often in the form of superphosphate of lime, a mixture of calcium dihydrogen phosphate (Ca(H2PO4)2), and calcium sulfate dihydrate (CaSO4·2H2O) produced reacting sulfuric acid and water with calcium phosphate.

Processing phosphate minerals with sulfuric acid for obtaining fertiliser is so important to the global economy that this is the primary industrial market for sulfuric acid and the greatest industrial use of elemental sulfur.[82]

| Widely used compounds | Use |

|---|---|

| Ca(H2PO4)2·H2O | Baking powder and fertilisers |

| CaHPO4·2H2O | Animal food additive, toothpowder |

| H3PO4 | Manufacture of phosphate fertilisers |

| PCl3 | Manufacture of POCl3 and pesticides |

| POCl3 | Manufacture of plasticiser |

| P4S10 | Manufacturing of additives and pesticides |

| Na5P3O10 | Detergents |

Organophosphorus

White phosphorus is widely used to make organophosphorus compounds through intermediate phosphorus chlorides and two phosphorus sulfides, phosphorus pentasulfide and phosphorus sesquisulfide.[83] Organophosphorus compounds have many applications, including in plasticisers, flame retardants, pesticides, extraction agents, nerve agents and water treatment.[15][84]

Metallurgical aspects

Phosphorus is also an important component in steel production, in the making of phosphor bronze, and in many other related products.[85][86] Phosphorus is added to metallic copper during its smelting process to react with oxygen present as an impurity in copper and to produce phosphorus-containing copper (CuOFP) alloys with a higher hydrogen embrittlement resistance than normal copper.[87] Phosphate conversion coating is a chemical treatment applied to steel parts to improve their corrosion resistance.

Matches

The first striking match with a phosphorus head was invented by Charles Sauria in 1830. These matches (and subsequent modifications) were made with heads of white phosphorus, an oxygen-releasing compound (potassium chlorate, lead dioxide, or sometimes nitrate), and a binder. They were poisonous to the workers in manufacture,[88] sensitive to storage conditions, toxic if ingested, and hazardous when accidentally ignited on a rough surface.[89][90] Production in several countries was banned between 1872 and 1925.[91] The international Berne Convention, ratified in 1906, prohibited the use of white phosphorus in matches.

In consequence, phosphorous matches were gradually replaced by safer alternatives. Around 1900 French chemists Henri Sévène and Emile David Cahen invented the modern strike-anywhere match, wherein the white phosphorus was replaced by phosphorus sesquisulfide (P4S3), a non-toxic and non-pyrophoric compound that ignites under friction. For a time these safer strike-anywhere matches were quite popular but in the long run they were superseded by the modern safety match.

Safety matches are very difficult to ignite on any surface other than a special striker strip. The strip contains non-toxic red phosphorus and the match head potassium chlorate, an oxygen-releasing compound. When struck, small amounts of abrasion from match head and striker strip are mixed intimately to make a small quantity of Armstrong's mixture, a very touch sensitive composition. The fine powder ignites immediately and provides the initial spark to set off the match head. Safety matches separate the two components of the ignition mixture until the match is struck. This is the key safety advantage as it prevents accidental ignition. Nonetheless, safety matches, invented in 1844 by Gustaf Erik Pasch and market ready by the 1860s, did not gain consumer acceptance until the prohibition of white phosphorus. Using a dedicated striker strip was considered clumsy.[20][83][92]

Water softening

Sodium tripolyphosphate made from phosphoric acid is used in laundry detergents in some countries, but banned for this use in others.[22] This compound softens the water to enhance the performance of the detergents and to prevent pipe/boiler tube corrosion.[93]

Miscellaneous

- Phosphates are used to make special glasses for sodium lamps.[22]

- Bone-ash (mostly calcium phosphate) is used in the production of fine china.[22]

- Phosphoric acid made from elemental phosphorus is used in food applications such as soft drinks, and as a starting point for food grade phosphates.[83] These include monocalcium phosphate for baking powder and sodium tripolyphosphate.[83] Phosphates are used to improve the characteristics of processed meat and cheese, and in toothpaste.[83]

- White phosphorus, called "WP" (slang term "Willie Peter") is used in military applications as incendiary bombs, for smoke-screening as smoke pots and smoke bombs, and in tracer ammunition. It is also a part of an obsolete M34 White Phosphorus US hand grenade. This multipurpose grenade was mostly used for signaling, smoke screens, and inflammation; it could also cause severe burns and had a psychological impact on the enemy.[94] Military uses of white phosphorus are constrained by international law.

- 32P and 33P are used as radioactive tracers in biochemical laboratories.[95]

Biological role

Inorganic phosphorus in the form of the phosphate PO3−

4 is required for all known forms of life.[96] Phosphorus plays a major role in the structural framework of DNA and RNA. Living cells use phosphate to transport cellular energy with adenosine triphosphate (ATP), necessary for every cellular process that uses energy. ATP is also important for phosphorylation, a key regulatory event in cells. Phospholipids are the main structural components of all cellular membranes. Calcium phosphate salts assist in stiffening bones.[15] Biochemists commonly use the abbreviation "Pi" to refer to inorganic phosphate.[97]

Every living cell is encased in a membrane that separates it from its surroundings. Cellular membranes are composed of a phospholipid matrix and proteins, typically in the form of a bilayer. Phospholipids are derived from glycerol with two of the glycerol hydroxyl (OH) protons replaced by fatty acids as an ester, and the third hydroxyl proton has been replaced with phosphate bonded to another alcohol.[98]

An average adult human contains about 0.7 kg of phosphorus, about 85–90% in bones and teeth in the form of apatite, and the remainder in soft tissues and extracellular fluids. The phosphorus content increases from about 0.5% by mass in infancy to 0.65–1.1% by mass in adults. Average phosphorus concentration in the blood is about 0.4 g/L; about 70% of that is organic and 30% inorganic phosphates.[99] An adult with healthy diet consumes and excretes about 1–3 grams of phosphorus per day, with consumption in the form of inorganic phosphate and phosphorus-containing biomolecules such as nucleic acids and phospholipids; and excretion almost exclusively in the form of phosphate ions such as H

2PO−

4 and HPO2−

4. Only about 0.1% of body phosphate circulates in the blood, paralleling the amount of phosphate available to soft tissue cells.

Bone and teeth enamel

The main component of bone is hydroxyapatite as well as amorphous forms of calcium phosphate, possibly including carbonate. Hydroxyapatite is the main component of tooth enamel. Water fluoridation enhances the resistance of teeth to decay by the partial conversion of this mineral to the still harder material fluorapatite:[15]

- Ca

5(PO

4)

3OH + F−

→ Ca

5(PO

4)

3F + OH−

Phosphorus deficiency

In medicine, phosphate deficiency syndrome may be caused by malnutrition, by failure to absorb phosphate, and by metabolic syndromes that draw phosphate from the blood (such as in refeeding syndrome after malnutrition[100]) or passing too much of it into the urine. All are characterised by hypophosphatemia, which is a condition of low levels of soluble phosphate levels in the blood serum and inside the cells. Symptoms of hypophosphatemia include neurological dysfunction and disruption of muscle and blood cells due to lack of ATP. Too much phosphate can lead to diarrhoea and calcification (hardening) of organs and soft tissue, and can interfere with the body's ability to use iron, calcium, magnesium, and zinc.[101]

Phosphorus is an essential macromineral for plants, which is studied extensively in edaphology to understand plant uptake from soil systems. Phosphorus is a limiting factor in many ecosystems; that is, the scarcity of phosphorus limits the rate of organism growth. An excess of phosphorus can also be problematic, especially in aquatic systems where eutrophication sometimes leads to algal blooms.[39]

Nutrition

Dietary recommendations

The U.S. Institute of Medicine (IOM) updated Estimated Average Requirements (EARs) and Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for phosphorus in 1997. If there is not sufficient information to establish EARs and RDAs, an estimate designated Adequate Intake (AI) is used instead. The current EAR for phosphorus for people ages 19 and up is 580 mg/day. The RDA is 700 mg/day. RDAs are higher than EARs so as to identify amounts that will cover people with higher than average requirements. RDA for pregnancy and lactation are also 700 mg/day. For people ages 1–18 years the RDA increases with age from 460 to 1250 mg/day. As for safety, the IOM sets Tolerable upper intake levels (ULs) for vitamins and minerals when evidence is sufficient. In the case of phosphorus the UL is 4000 mg/day. Collectively the EARs, RDAs, AIs and ULs are referred to as Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs).[102]

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) refers to the collective set of information as Dietary Reference Values, with Population Reference Intake (PRI) instead of RDA, and Average Requirement instead of EAR. AI and UL are defined the same as in the United States. For people ages 15 and older, including pregnancy and lactation, the AI is set at 550 mg/day. For children ages 4–10 the AI is 440 mg/day, and for ages 11–17 it is 640 mg/day. These AIs are lower than the U.S. RDAs. In both systems, teenagers need more than adults.[103] The European Food Safety Authority reviewed the same safety question and decided that there was not sufficient information to set a UL.[104]

For U.S. food and dietary supplement labeling purposes the amount in a serving is expressed as a percent of Daily Value (%DV). For phosphorus labeling purposes 100% of the Daily Value was 1000 mg, but as of May 27, 2016 it was revised to 1250 mg to bring it into agreement with the RDA.[105][106] A table of the old and new adult daily values is provided at Reference Daily Intake.

Food sources

The main food sources for phosphorus are the same as those containing protein, although proteins do not contain phosphorus. For example, milk, meat, and soya typically also have phosphorus. As a rule, if a diet has sufficient protein and calcium, the amount of phosphorus is probably sufficient.[107]

Precautions

Organic compounds of phosphorus form a wide class of materials; many are required for life, but some are extremely toxic. Fluorophosphate esters are among the most potent neurotoxins known. A wide range of organophosphorus compounds are used for their toxicity as pesticides (herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, etc.) and weaponised as nerve agents against enemy humans. Most inorganic phosphates are relatively nontoxic and essential nutrients.[15]

The white phosphorus allotrope presents a significant hazard because it ignites in the air and produces phosphoric acid residue. Chronic white phosphorus poisoning leads to necrosis of the jaw called "phossy jaw". White phosphorus is toxic, causing severe liver damage on ingestion and may cause a condition known as "Smoking Stool Syndrome".[108]

In the past, external exposure to elemental phosphorus was treated by washing the affected area with 2% copper(II) sulfate solution to form harmless compounds that are then washed away. According to the recent US Navy's Treatment of Chemical Agent Casualties and Conventional Military Chemical Injuries: FM8-285: Part 2 Conventional Military Chemical Injuries, "Cupric (copper(II)) sulfate has been used by U.S. personnel in the past and is still being used by some nations. However, copper sulfate is toxic and its use will be discontinued. Copper sulfate may produce kidney and cerebral toxicity as well as intravascular hemolysis."[109]

The manual suggests instead "a bicarbonate solution to neutralise phosphoric acid, which will then allow removal of visible white phosphorus. Particles often can be located by their emission of smoke when air strikes them, or by their phosphorescence in the dark. In dark surroundings, fragments are seen as luminescent spots. Promptly debride the burn if the patient's condition will permit removal of bits of WP (white phosphorus) that might be absorbed later and possibly produce systemic poisoning. DO NOT apply oily-based ointments until it is certain that all WP has been removed. Following complete removal of the particles, treat the lesions as thermal burns."[note 1] As white phosphorus readily mixes with oils, any oily substances or ointments are not recommended until the area is thoroughly cleaned and all white phosphorus removed.

People can be exposed to phosphorus in the workplace by inhalation, ingestion, skin contact, and eye contact. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set the phosphorus exposure limit (Permissible exposure limit) in the workplace at 0.1 mg/m3 over an 8-hour workday. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set a Recommended exposure limit (REL) of 0.1 mg/m3 over an 8-hour workday. At levels of 5 mg/m3, phosphorus is immediately dangerous to life and health.[110]

US DEA List I status

Phosphorus can reduce elemental iodine to hydroiodic acid, which is a reagent effective for reducing ephedrine or pseudoephedrine to methamphetamine.[111] For this reason, red and white phosphorus were designated by the United States Drug Enforcement Administration as List I precursor chemicals under 21 CFR 1310.02 effective on November 17, 2001.[112] In the United States, handlers of red or white phosphorus are subject to stringent regulatory controls.[112][113][114]

Notes

- ↑ WP, (white phosphorus), exhibits chemoluminescence upon exposure to air and if there is any WP in the wound, covered by tissue or fluids such as blood serum, it will not glow until it is exposed to air, which requires a very dark room and dark-adapted eyes to see clearly

References

- ↑ "Standard Atomic Weights: Phosphorus". CIAAW. 2013.

- ↑ "Phosphorus: Chemical Element". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Wang, Yuzhong; Xie, Yaoming; Wei, Pingrong; King, R. Bruce; Schaefer, Iii; Schleyer, Paul v. R.; Robinson, Gregory H. (2008). "Carbene-Stabilized Diphosphorus". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 130 (45): 14970–1. doi:10.1021/ja807828t. PMID 18937460.

- ↑ Ellis, Bobby D.; MacDonald, Charles L. B. (2006). "Phosphorus(I) Iodide: A Versatile Metathesis Reagent for the Synthesis of Low Oxidation State Phosphorus Compounds". Inorganic Chemistry. 45 (17): 6864–74. doi:10.1021/ic060186o. PMID 16903744.

- ↑ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). "Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds". CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (PDF) (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ↑ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ↑ cf. "Memoir on Combustion in General" Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences 1777, 592–600. from Henry Marshall Leicester and Herbert S. Klickstein, A Source Book in Chemistry 1400–1900 (New York: McGraw Hill, 1952)

- 1 2 A. Holleman; N. Wiberg (1985). "XV 2.1.3". Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (33rd ed.). de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-012641-9.

- 1 2 Abundance. ptable.com

- ↑ Simon, Arndt; Borrmann, Horst; Horakh, Jörg (1997). "On the Polymorphism of White Phosphorus". Chemische Berichte. 130 (9): 1235–1240. doi:10.1002/cber.19971300911.

- 1 2 Cossairt, Brandi M.; Cummins, Christopher C.; Head, Ashley R.; Lichtenberger, Dennis L.; Berger, Raphael J. F.; Hayes, Stuart A.; Mitzel, Norbert W.; Wu, Gang (2010-06-01). "On the Molecular and Electronic Structures of AsP3 and P4". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 132 (24): 8459–8465. doi:10.1021/ja102580d. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 20515032.

- ↑ Welford C. Roberts; William R. Hartley (1992-06-16). Drinking Water Health Advisory: Munitions (illustrated ed.). CRC Press, 1992. p. 399. ISBN 0-87371-754-6.

- ↑ Marie-Thérèse Averbuch-Pouchot; A. Durif (1996). Topics in Phosphate Chemistry. World Scientific, 1996. p. 3. ISBN 981-02-2634-9.

- ↑ Simon, Arndt; Borrmann, Horst; Horakh, Jörg (September 1997). "On the Polymorphism of White Phosphorus". Chemische Berichte. 130 (9): 1235–1240. doi:10.1002/cber.19971300911. ISSN 0009-2940.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Greenwood, N. N.; & Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd Edn.), Oxford:Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4.

- ↑ Piro, N. A.; Figueroa, J. S.; McKellar, J. T.; Cummins, C. C. (2006). "Triple-Bond Reactivity of Diphosphorus Molecules". Science. 313 (5791): 1276–9. Bibcode:2006Sci...313.1276P. doi:10.1126/science.1129630. PMID 16946068. S2CID 27740669.

- 1 2 3 Berger, L. I. (1996). Semiconductor materials. CRC Press. p. 84. ISBN 0-8493-8912-7.

- ↑ Shen, Z; Yu, JC (2016). "Nanostructured elemental photocatalysts: Development and challenges". In Yamashita, H; Li, H (eds.). Nanostructured Photocatalysts: Advanced Functional Materials. Switzerland: Springer. pp. 295–312 (301). ISBN 978-3-319-26077-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Parkes & Mellor 1939, p. 717

- 1 2 Egon Wiberg; Nils Wiberg; Arnold Frederick Holleman (2001). Inorganic chemistry. Academic Press. pp. 683–684, 689. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9. Retrieved 2011-11-19.

- ↑ Parkes & Mellor 1939, pp. 721–722

- 1 2 3 4 Hammond, C. R. (2000). The Elements, in Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (81st ed.). CRC press. ISBN 0-8493-0481-4.

- ↑ A. Brown; S. Runquist (1965). "Refinement of the crystal structure of black phosphorus". Acta Crystallogr. 19 (4): 684–685. doi:10.1107/S0365110X65004140.

- ↑ Cartz, L.; Srinivasa, S.R.; Riedner, R.J.; Jorgensen, J.D.; Worlton, T.G. (1979). "Effect of pressure on bonding in black phosphorus". Journal of Chemical Physics. 71 (4): 1718–1721. Bibcode:1979JChPh..71.1718C. doi:10.1063/1.438523.

- ↑ Lange, Stefan; Schmidt, Peer & Nilges, Tom (2007). "Au3SnP7@Black Phosphorus: An Easy Access to Black Phosphorus". Inorg. Chem. 46 (10): 4028–35. doi:10.1021/ic062192q. PMID 17439206.

- ↑ Robert Engel (2003-12-18). Synthesis of Carbon-Phosphorus Bonds (2 ed.). CRC Press, 2003. p. 11. ISBN 0-203-99824-3.

- ↑ "Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1956 – Presentation Speech by Professor A. Ölander (committee member)". Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "Phosphorus Topics page, at Lateral Science". Archived from the original on 2009-02-21. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- 1 2 3 Emsley, John (2000). The Shocking History of Phosphorus. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-330-39005-8.

- ↑ Vanzee, Richard J.; Khan, Ahsan U. (1976). "The phosphorescence of phosphorus". The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 80 (20): 2240–2242. doi:10.1021/j100561a021.

- 1 2 Michael A. Sommers (2007-08-15). Phosphorus. The Rosen Publishing Group, 2007. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-4042-1960-1.

- ↑ Audi, G.; Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S. (2017). "The NUBASE2016 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 41 (3): 030001. Bibcode:2017ChPhC..41c0001A. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/41/3/030001.

- ↑ Neufcourt, L.; Cao, Y.; Nazarewicz, W.; Olsen, E.; Viens, F. (2019). "Neutron drip line in the Ca region from Bayesian model averaging". Physical Review Letters. 122 (6): 062502–1–062502–6. arXiv:1901.07632. Bibcode:2019PhRvL.122f2502N. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.062502. PMID 30822058. S2CID 73508148.

- ↑ "Phosphorus-32" (PDF). University of Michigan Department of Occupational Safety & Environmental Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-05-28. Retrieved 2010-11-18.

- ↑ Koo, B.-C.; Lee, Y.-H.; Moon, D.-S.; Yoon, S.-C.; Raymond, J. C. (2013). "Phosphorus in the Young Supernova Remnant Cassiopeia A". Science. 342 (6164): 1346–8. arXiv:1312.3807. Bibcode:2013Sci...342.1346K. doi:10.1126/science.1243823. PMID 24337291. S2CID 35593706.

- ↑ Rivilla, V. M.; Drozdovskaya, M. N.; Altwegg, K.; Caselli, P.; Beltrán, M. T.; Fontani, F.; van der Tak, F. F. S.; Cesaroni, R.; Vasyunin, A.; Rubin, M.; Lique, F.; Marinakis, S.; Testi, L. (2019). "ALMA and ROSINA detections of phosphorus-bearing molecules: the interstellar thread between star-forming regions and comets". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 492: 1180–1198. arXiv:1911.11647. doi:10.1093/mnras/stz3336. S2CID 208290964.

- ↑ ESO (15 January 2020). "Astronomers reveal interstellar thread of one of life's building blocks". Phys.org. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ↑ "Phosphate Rock: Statistics and Information". USGS. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Philpott, Tom (March–April 2013). "You Need Phosphorus to Live—and We're Running Out". Mother Jones.

- ↑ Klein, Cornelis and Cornelius S. Hurlbut, Jr., Manual of Mineralogy, Wiley, 1985, 20th ed., p. 360, ISBN 0-471-80580-7

- ↑ Threlfall 1951, p. 51

- ↑ Arthur D. F. Toy (2013-10-22). The Chemistry of Phosphorus. Elsevier, 2013. p. 389. ISBN 978-1-4831-4741-3.

- ↑ D. E. C. Corbridge "Phosphorus: An Outline of its Chemistry, Biochemistry, and Technology" 5th Edition Elsevier: Amsterdam 1995. ISBN 0-444-89307-5.

- ↑ Kutzelnigg, W. (1984). "Chemical Bonding in Higher Main Group Elements" (PDF). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 23 (4): 272–295. doi:10.1002/anie.198402721. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-04-16. Retrieved 2009-05-24.

- ↑ Mark, J. E.; Allcock, H. R.; West, R. "Inorganic Polymers" Prentice Hall, Englewood, NJ: 1992. ISBN 0-13-465881-7.

- ↑ Heal, H. G. "The Inorganic Heterocyclic Chemistry of Sulfur, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus" Academic Press: London; 1980. ISBN 0-12-335680-6.

- ↑ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). "The discovery of the elements. II. Elements known to the alchemists". Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (1): 11. Bibcode:1932JChEd...9...11W. doi:10.1021/ed009p11.

- ↑ Beatty, Richard (2000). Phosphorus. Marshall Cavendish. p. 7. ISBN 0-7614-0946-7.

- 1 2 Schmundt, Hilmar (21 April 2010), "Experts Warn of Impending Phosphorus Crisis", Der Spiegel.

- ↑ Stillman, J. M. (1960). The Story of Alchemy and Early Chemistry. New York: Dover. pp. 418–419. ISBN 0-7661-3230-7.

- ↑ Baccini, Peter; Paul H. Brunner (2012-02-10). Metabolism of the Anthroposphere. MIT Press, 2012. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-262-30054-4.

- ↑ Emsley, John (7 January 2002). The 13th Element: The Sordid Tale of Murder, Fire, and Phosphorus. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-44149-6. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ↑ cf. "Memoir on Combustion in General" Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences 1777, 592–600. from Henry Marshall Leicester and Herbert S. Klickstein, A Source Book in Chemistry 1400–1900 (New York: McGraw Hill, 1952)

- ↑ Thomson, Robert Dundas (1870). Dictionary of chemistry with its applications to mineralogy, physiology and the arts. Rich. Griffin and Company. p. 416.

- ↑ Threlfall 1951, pp. 49–66

- ↑ Robert B. Heimann; Hans D. Lehmann (2015-03-10). Bioceramic Coatings for Medical Implants. John Wiley & Sons, 2015. p. 4. ISBN 978-3-527-68400-7.

- ↑ The Chemistry of Phosphorus, by Arthur Toy

- ↑ US patent 417943

- ↑ Threlfall 1951, pp. 81–101

- ↑ Parkes & Mellor 1939, p. 718–720.

- 1 2 3 Threlfall 1951, pp. 167–185

- ↑ Lewis R. Goldfrank; Neal Flomenbaum; Mary Ann Howland; Robert S. Hoffman; Neal A. Lewin; Lewis S. Nelson (2006). Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 1486–1489. ISBN 0-07-143763-0.

- ↑ The White Phosphorus Matches Prohibition Act, 1908.

- ↑ "Phosphate Rock" (PDF). USGS. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- ↑ Lewis, Leo (2008-06-23). "Scientists warn of lack of vital phosphorus as biofuels raise demand". The Times.

- ↑ Grantham, Jeremy (Nov 12, 2012). "Be persuasive. Be brave. Be arrested (if necessary)". Nature. 491 (7424): 303. Bibcode:2012Natur.491..303G. doi:10.1038/491303a. PMID 23151541.

- 1 2 Geeson, Michael B.; Cummins, Christopher C. (2020). "Let's Make White Phosphorus Obsolete". ACS Central Science. 6 (6): 848–860. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.0c00332. PMC 7318074. PMID 32607432.

- ↑ Tayibi, Hanan; Choura, Mohamed; López, Félix A.; Alguacil, Francisco J.; López-Delgado, Aurora (2009). "Environmental Impact and Management of Phosphogypsum". Journal of Environmental Management. 90 (8): 2377–2386. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.03.007. hdl:10261/45241. PMID 19406560.

- ↑ Shriver, Atkins. Inorganic Chemistry, Fifth Edition. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York; 2010; p. 379.

- ↑ "ERCO and Long Harbour". Memorial University of Newfoundland and the C.R.B. Foundation. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ↑ Von Wagner, Rudolf (1897). Manual of chemical technology. New York: D. Appleton & Co. p. 411.

- ↑ Naiker, Vidhukrishnan E.; Mestry, Siddhesh; Nirgude, Tejal; Gadgeel, Arjit; Mhaske, S. T. (2023-01-01). "Recent developments in phosphorous-containing bio-based flame-retardant (FR) materials for coatings: an attentive review". Journal of Coatings Technology and Research. 20 (1): 113–139. doi:10.1007/s11998-022-00685-z. ISSN 1935-3804. S2CID 253349703.

- ↑ "Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers". Foods Standards Agency. 14 March 2012. Archived from the original on 21 August 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ↑ "Why is phosphoric acid used in some Coca‑Cola drinks?| Frequently Asked Questions | Coca-Cola GB". www.coca-cola.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 2021-08-31.

- ↑ Moynihan, P. J. (23 November 2002). "Dietary advice in dental practice". British Dental Journal. 193 (10): 563–568. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4801628. PMID 12481178.

- ↑ Qaseem, A; Dallas, P; Forciea, MA; Starkey, M; et al. (4 November 2014). "Dietary and pharmacologic management to prevent recurrent nephrolithiasis in adults: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 161 (9): 659–67. doi:10.7326/M13-2908. PMID 25364887.

- 1 2 Etesami, H. (2019). Nutrient Dynamics for Sustainable Crop Production. Springer. p. 217. ISBN 978-981-13-8660-2.

- ↑ Carpenter, Stephen R. (2005). "Eutrophication of aquatic ecosystems: Bistability and soil phosphorus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (29): 10002–10005. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503959102. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1177388. PMID 15972805.

- ↑ Conley, Daniel J.; Paerl, Hans W.; Howarth, Robert W.; et al. (2009). "Controlling Eutrophication: Nitrogen and Phosphorus". Science. 323 (5917): 1014–1015. doi:10.1126/science.1167755. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ↑ "Soil Phosphorous" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-10-28. Retrieved 2020-08-17.

- ↑ "Managing Phosphorus for Crop Production". Penn State Extension. Archived from the original on 2020-10-20. Retrieved 2020-08-17.

- ↑ Jessica Elzea Kogel, ed. (2006). Industrial Minerals & Rocks: Commodities, Markets, and Uses. SME, 2006. p. 964. ISBN 0-87335-233-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Threlfall, R.E. (1951). 100 years of Phosphorus Making: 1851–1951. Oldbury: Albright and Wilson Ltd.

- ↑ Diskowski, Herbert and Hofmann, Thomas (2005) "Phosphorus" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_505

- ↑ Roland W. Scholz; Amit H. Roy; Fridolin S. Brand; Deborah Hellums; Andrea E. Ulrich, eds. (2014-03-12). Sustainable Phosphorus Management: A Global Transdisciplinary Roadmap. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 175. ISBN 978-94-007-7250-2.

- ↑ Mel Schwartz (2016-07-06). Encyclopedia and Handbook of Materials, Parts and Finishes. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-138-03206-4.

- ↑ Joseph R. Davisz, ed. (January 2001). Copper and Copper Alloys. ASM International. p. 181. ISBN 0-87170-726-8.

- ↑ Hughes, J. P. W; Baron, R.; Buckland, D. H.; et al. (1962). "Phosphorus Necrosis of the Jaw: A Present-day Study: With Clinical and Biochemical Studies". Br. J. Ind. Med. 19 (2): 83–99. doi:10.1136/oem.19.2.83. PMC 1038164. PMID 14449812.

- ↑ Crass, M. F. Jr. (1941). "A history of the match industry. Part 9" (PDF). Journal of Chemical Education. 18 (9): 428–431. Bibcode:1941JChEd..18..428C. doi:10.1021/ed018p428.

- ↑ Oliver, Thomas (1906). "Industrial disease due to certain poisonous fumes or gases". Archives of the Public Health Laboratory. Manchester University Press. 1: 1–21.

- ↑ Charnovitz, Steve (1987). "The Influence of International Labour Standards on the World Trading Regime. A Historical Overview". International Labour Review. 126 (5): 565, 571.

- ↑ Alexander P. Hardt (2001). "Matches". Pyrotechnics. Post Falls Idaho USA: Pyrotechnica Publications. pp. 74–84. ISBN 0-929388-06-2.

- ↑ Klaus Schrödter, Gerhard Bettermann, Thomas Staffel, Friedrich Wahl, Thomas Klein, Thomas Hofmann "Phosphoric Acid and Phosphates" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2008, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_465.pub3

- ↑ Dockery, Kevin (1997). Special Warfare Special Weapons. Chicago: Emperor's Press. ISBN 1-883476-00-3.

- ↑ David A. Atwood, ed. (2013-02-19). Radionuclides in the Environment. John Wiley & Sons, 2013. ISBN 978-1-118-63269-7.

- ↑ Ruttenberg, K. C. Phosphorus Cycle – Terrestrial Phosphorus Cycle, Transport of Phosphorus, from Continents to the Ocean, The Marine Phosphorus Cycle. (archived link).

- ↑ Lipmann, D. (1944). "Enzymatic Synthesis of Acetyl Phosphate". J Biol Chem. 155: 55–70. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)43172-9.

- ↑ Nelson, D. L.; Cox, M. M. "Lehninger, Principles of Biochemistry" 3rd Ed. Worth Publishing: New York, 2000. ISBN 1-57259-153-6.

- ↑ Bernhardt, Nancy E.; Kasko, Artur M. (2008). Nutrition for the Middle Aged and Elderly. Nova Publishers. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-60456-146-3.

- ↑ Mehanna H. M.; Moledina J.; Travis J. (June 2008). "Refeeding syndrome: what it is, and how to prevent and treat it". BMJ. 336 (7659): 1495–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.a301. PMC 2440847. PMID 18583681.

- ↑ Anderson, John J. B. (1996). "Calcium, Phosphorus and Human Bone Development". Journal of Nutrition. 126 (4 Suppl): 1153S–1158S. doi:10.1093/jn/126.suppl_4.1153S. PMID 8642449.

- ↑ Institute of Medicine (1997). "Phosphorus". Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Vitamin D, and Fluoride. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. pp. 146–189. doi:10.17226/5776. ISBN 978-0-309-06403-3. PMID 23115811. S2CID 8768378.

- ↑ "Overview on Dietary Reference Values for the EU population as derived by the EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies" (PDF). 2017.

- ↑ Tolerable Upper Intake Levels For Vitamins And Minerals (PDF), European Food Safety Authority, 2006

- ↑ "Federal Register May 27, 2016 Food Labeling: Revision of the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels. FR page 33982" (PDF).

- ↑ "Daily Value Reference of the Dietary Supplement Label Database (DSLD)". Dietary Supplement Label Database (DSLD). Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ↑ Phosphorus in diet: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Nlm.nih.gov (2011-11-07). Retrieved on 2011-11-19.

- ↑ "CBRNE – Incendiary Agents, White Phosphorus (Smoking Stool Syndrome)". Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "US Navy's Treatment of Chemical Agent Casualties and Conventional Military Chemical Injuries: FM8-285: Part 2 Conventional Military Chemical Injuries". Archived from the original on November 22, 2005. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards - Phosphorus (yellow)". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-21.

- ↑ Skinner, H.F. (1990). "Methamphetamine synthesis via hydriodic acid/red phosphorus reduction of ephedrine". Forensic Science International. 48 (2): 123–134. doi:10.1016/0379-0738(90)90104-7.

- 1 2 "66 FR 52670—52675". 17 October 2001. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "21 cfr 1309". Archived from the original on 2009-05-03. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "21 USC, Chapter 13 (Controlled Substances Act)". Retrieved 2009-05-05.

Bibliography

- Emsley, John (2000). The Shocking history of Phosphorus. A biography of the Devil's Element. London: MacMillan. ISBN 0-333-76638-5.

- Parkes, G. D.; Mellor, J. W. (1939). Mellor's Modern Inorganic Chemistry. Longman's Green and Co.

- Podger, Hugh (2002). Albright & Wilson. The Last 50 years. Studley: Brewin Books. ISBN 1-85858-223-7.

- Threlfall, Richard E. (1951). The Story of 100 years of Phosphorus Making: 1851–1951. Oldbury: Albright & Wilson Ltd.

Further reading

- Kolbert, Elizabeth, "Elemental Need: Phosphorus helped save our way of life – and now threatens to end it", The New Yorker, 6 March 2023, pp. 24–27. "[T]he world's phosphorus problem [arising from the element's exorbitant use in agriculture] resembles its carbon-dioxide problem, its plastics problem, its groundwater-use problem, its soil-erosion problem, and its nitrogen problem. The path humanity is on may lead to ruin, but, as of yet, no one has found a workable way back." (p. 27.)