Pierre Boaistuau, also known as Pierre Launay or Sieur de Launay (c. 1517, Nantes – 1566, Paris), was a French Renaissance humanist writer, author of a number of popularizing compilations and discourses on various subjects.[1]

Beside his many popular titles as a writer, Boaistuau was also an editor, translator and compiler. He holds a very special place in literary developments in the middle and second half of the sixteenth century as the importer of two influential genres in France, the 'histoire tragique' and the 'histoire prodigieuse'. He was also the first editor of Marguerite of Navarre's collection of nouvelles that is known today as Heptameron.

Life

Boaistuau was born in Nantes and later studied civil and canon law in the universities of Poitiers, Valence (where he was a student of the eminent jurist Jean de Coras), and Avignon (where he studied under the guidance of Emilio Ferretti). During his student years, he worked as the secretary of the French ambassador to the East Jean-Jacques of Cambrai around 1550, and traveled to Italy and Germany. Ernst Courbet put forth the hypothesis that Boaistuau had also been for some time a 'valet de chambre' of Marguerite of Navarre, an assertion which however can not be substantiated.[2] Later, the writer also visited England and Scotland on his own, and met with Elizabeth I.

Works

His most successful titles in terms of publications were Le Théâtre du monde (which became one of early modern Europe's best-sellers), Histoires prodigieuses, and Histoires tragiques. As the contents of his works indicate, his varied interests included, among other, political theory, history, philosophy, literary fiction, theology, ecclesiastical history, and natural philosophy. Enjoying a certain degree of fame due to the success of his books, Boaistuau's network of friends and contacts included many well-known French literati of his time, such as François de Belleforest, Joseph Scaliger, Bernard de Girard, Nicolas Denisot, Jean-Antoine de Baïf, Claude Roillet, and Jacques Grévin. He was also in friendly terms with James Beaton II, ex-Archbishop of Glasgow and Scottish ambassador in Paris, to whom he dedicated his Le Théâtre du monde.

Works

- L'Histoire de Chelidonius Tigurinus (Paris, 1556) - A political discourse focusing mainly on the education of the ideal Christian prince and his qualities, proclaiming monarchy as the most profitable political system.

- Histoires des amans fortunez (Paris, 1558) - A collection of nouvelles of love and betrayal, written in the style of Boccaccio’s Decameron. Originally attributed to Marguerite of Navarre, this work was renamed to Heptameron in 1559.

- Le Théâtre du monde (Paris, 1558) - Divided into three main sections, this philosophical treatise deals with the miseries of Man, and the various kinds of adversities (e.g. wars, diseases, famines, etc.) he has to endure during his lifetime.

- Bref discours de l’excellence et dignité de l’homme (Paris, 1559) - A discourse on Man's virtues and abilities, praising both his body and mind. Soon after its first publication as a separate work, it also appeared as a supplement of Le Théâtre du monde.

- Histoires tragiques (Paris, 1559) - A collection of six cautionary tales taken from Matteo Bandello's Novelle and translated into French. The third story entitled 'Histoire troisieme de deux Amants, don't l'un mourut de venin, l'autre de tristesse' influenced William Shakespeare to write his Romeo and Juliet.

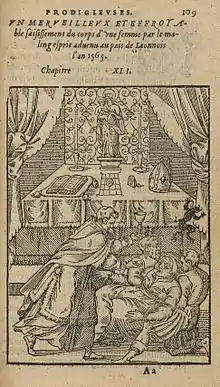

- Histoires prodigieuses (Paris, 1560) - A collection of extraordinary stories of monstrous births, demons, sea-monsters, serpents, creatures half-man and half-animal, precious stones, floods, comets, earthquakes and other natural phenomena.

- Histoire des persecutions de l’Eglise chrestienne et catholique (Paris, 1572) - A narration of the afflictions of the early Christian Church during the time of the Roman Empire. This work was published posthumously and is most probably a French translation of an earlier work.

References

- ↑ 'Boaistuau' seems to be the best authenticated spelling and is used by the majority of secondary works. However, alternate spellings of the writer's surname appear in the multitude of editions of his works. Some examples include Boistuau, Boiastuau, Boaisteau, Boisteau, Boaystuau, Boysteau, Bouaistuau, Bouesteau, Bouaystuau, Bosteau, Baistuau, and Boiestuau.

- ↑ Courbet, E., ‘Jean d’ Albret et l’Heptaméron’, Bulletin du Bibliophile et Bibliothécaire (1904), pp. 277-290.

External links

- Olin H. Moore, The Legend of Romeo and Juliet (The Ohio State University Press, 1950), chapter X: Pierre Boaistuau

- Nancy E. Virtue, 'Translation as Violation: A Reading of Pierre Boaistuau's Histoires Tragiques', Renaissance and Reformation, vol. 22, No 3 (1998), pp. 35-58.

- Pierre Boaistuau's Histoires Prodigieuses at the site of the Wellcome Collection

- Pierre Boaistuau at the WorldCat