Pierre César Charles de Sercey | |

|---|---|

_-_Antoine_Maurin.png.webp) Pierre César Charles, Marquis de Sercey, lithograph, by Antoine Maurin, 1836. | |

| Born | 26 April 1753 La Comelle, Burgundy, France |

| Died | 10 August 1836 Paris, Île-de-France, France |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | French Navy |

| Years of service | 1766-1804 |

| Rank | Vice Admiral |

| Commands held | Indian Ocean Division |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War Haitian Revolution French Revolutionary Wars |

| Awards | Peer of France Grand-croix of the Legion of Honour Grand-croix of the Order of Saint Louis Society of the Cincinnati |

| Children | Édouard, comte de Sercey |

| Relations | Félicité, comtesse de Genlis |

| Signature | |

Vice Admiral Pierre César Charles Guillaume, Marquis de Sercey, born at the Château du Jeu, La Comelle on 26 April 1753 and died in Paris, 1st arrondissement on 10 August 1836, was a French naval officer and politician. He is best known for his service in the American Revolutionary War, his role in Saint-Domingue and the Mascarene Islands, and for commanding the French naval forces in the Indian Ocean from 1796 to 1800.

Early life

Coming from old Burgundian nobility,[1] he lost his father Jean-Jacques, Marquis de Sercey, captain of the Lorraine Dragoon Regiment, at the age of five. His family moved to Paris, and at thirteen he obtained permission from his mother Marie-Madeleine du Crest, shortly before her death, to join the Royal Navy, inspired by the exploits of a brother who had distinguished himself during the boarding of an English ship.[2] Now an orphan, he embarked in 1766 as a volunteer on the frigate Légère,[3] leaving Brest for a nine-month campaign in the Windward Islands. Back in France, he embarked in Lorient on the corvette Heure-du-Berger[3] for a twenty-seven month campaign in the Indian Ocean, at the end of which in 1770 he obtained the rank of garde-marine, sealing his engagement in the French Navy.[2]

Disembarking at the Isle de France, he immediately went on to serve on the frigate Ambulante for a new two-year campaign in the Indian Ocean.[3] In 1772, he joined the explorer Yves Joseph de Kerguelen, then in Port-Louis, in his first campaign of discovery of the southern Indian Ocean. He served on the fluyt Gros Ventre,[3] as Louis Aleno de Saint-Aloüarn's second-in-command, and thus took part in the discovery of the Kerguelen Islands.[4] Separated from the expedition's lead ship, the frigate Fortune, by a storm, Gros Ventre was considered lost and Kerguelen returned to France, claiming to King Louis XV to have discovered a new southern continent and obtaining the means for a new expedition. Gros Ventre instead continued its initial mission, heading towards Australia, the contours of which were still poorly understood. After a difficult voyage, Shark Bay in Western Australia was reached and Saint-Aloüarn took possession of it in the name of the King of France on 30 March 1772. A few months later, Sercey joined the second Kerguelen expedition on the Isle de France and served on board the frigate Oiseau,[3] this time participating in the more detailed reconnaissance of the Kerguelen, until 1774.

After this thirty-two month voyage, he returned to France and received a gratuity from King Louis XVI.[4] In 1775, he served on the Amphitrite[3] in the West Indies, more particularly around Saint-Domingue, under the command of the Comte de Grasse, then served on the famous Boudeuse,[3] attached to the station of the Leeward Islands, until 1778.[4]

American Revolutionary War

Sercey returned to France in June 1778, as tensions with Great Britain ran high because of French support for American revolutionaries in the American War of Independence. On 17 June, hostilities officially began after the French frigate Belle Poule clashed with the British frigate HMS Arethusa in the Channel. Sent to rescue the Belle Poule damaged in this victorious battle, with a hundred sailors, it was the Marquis de Sercey who led the ship from Plouescat Bay to Brest, in sight of the enemy, as its commander the Seigneur de la Clocheterie had been wounded during the confrontation.[5] He remained on this ship, becoming its second-in-command and then its temporary commander. Assigned to a naval division under the orders of Comte de Tréville, he served for seven months in the Atlantic Ocean, capturing three ships.[5] He reached the rank of ensign in May 1779 and served successively on the Triton, the Couronne, the Ville de Paris, and then on the frigate Concorde,[3] before being given command of the cutter Sans-Pareil, a British privateer ship, the Non Such, captured by Concorde and renamed. Placed under the command of the Comte de Guichen, he was sent to scout the Windward Islands with a small squadron, but was ambushed by eight privateers, an encounter from which he escaped with difficulty.[6] He rejoined the Comte de Guichen for the battle of Martinique in April 1780, then, in charge of carrying missives to Saint-Domingue, he found himself upon a British naval division at night and was taken prisoner by HMS Phoenix on 26 June 1780.[6]

He was exchanged in October of the same year, and obtained the command of the cutter Serpent,[3] then quickly that of Levrette.[3] It was while commanding the Levrette, assigned to a naval division under the command of François-Aymar de Monteil, that he participated in the siege of Pensacola and obtained a commission as a lieutenant when the city was taken in May 1781, as a reward for his accomplishments during the battle.[6] Upon his return to Hispaniola, he was assigned to escort with his cutter and a small frigate under his command, Fée, a convoy of thirty ships bound for New England.[6] Caught in pursuit by two English frigates, he armed a large ship, Tigre, and chose to go on the offensive: the enemy, superior but surprised by this daring maneuver, withdrew, and the convoy arrived intact at its destination.[6] Now loaded with messages for France, he lost Levrette in a storm off the Azores, but managed to save his cargo and arrived in port in time to warn the authorities of the arrival of an important convoy, escorted by Actionnaire.[7] As a reward, he was made chevalier of the Royal and Military Order of Saint Louis in May 1782.[3]

Embarked as a lieutenant on the frigate Nymphe and becoming second-in-command of the Vicomte de Mortemart, he participated with the Concorde in January 1783 in the recapture of HMS Raven, an English sloop captured in 1778, renamed Cérès, and then recaptured in April 1782 by the Viscount Hood.[7] A month later, he was with Amphitrite in the capture of HMS Argo, with on board the Governor of the British Leeward Islands, Thomas Shirley. It was Sercey, who, after bitter fighting and in the midst of a storm, embarked to take possession of the ship and its illustrious passenger.[7] Mortemart died of a sudden illness on their return to Saint-Domingue in March 1783, and the Marquis took command of Nymphe until the end of hostilities,[3] his last mission being to escort a convoy headed to Brest. He obtained from the king a pension and a letter of satisfaction.[8]

At the age of thirty, the Marquis de Sercey was far from retirement and was one of a limited number of officers who were allowed to remain in service. In 1784, he spent only a few months on land before embarking on the ship Séduisant,[3] which carried the French ambassador to the Sublime Porte Choiseul-Gouffier to Constantinople,[8] and then commanded Ariel,[3] a frigate stationed in the Windward Islands, from 1785 on.

Revolution, Saint-Domingue and the Mascarenes

Still stationed in the West Indies at the dawn of the French Revolution, Sercey did not take part in the events transpiring in France but was favourable to a certain extent to the ideas of the revolution.[9] In July 1790, he took command of the frigate Surveillante[3] in a division led by Counter Admiral Charles Louis du Chilleau de La Roche: he quickly faced mutiny among the men under his command, but with the experience of more than twenty years of service, he succeeded in bringing back calm and discipline.[8] He also succeeded in reasoning with the men of Jupiter who had taken their commander, Counter Admiral Joseph de Cambis, prisoner and returning them to their duties.[8] Promoted to the rank of captain on 1 January 1792,[3] he was assigned to a squadron under the command of Vice Admiral de Girardin, tasked with quelling the royalist rebellion then wrecking Martinique. In April 1792, he married Amélie de Sercey, his niece, daughter of his elder brother who had settled in Saint-Domingue. He witnessed the frantic developments of the first days of the Haitian revolution and Surveillante became the refuge of many colonists fleeing the slave revolt: he took in, for example, about a hundred inhabitants of Cayes and took care of them at his own expense for several months.[10]

Promoted to the rank of Counter Admiral on 1 January 1793,[3] he was appointed to head a naval division in charge of gathering all the commercial vessels still in the various ports of Saint-Domingue, and then to bring them back to the French mainland.[10] In April 1793 he left Brest on Éole[3] and upon his arrival in Cap-Français in June 1793, he discovered the capital of the French colony ravaged by political divisions between the supporters of the governor-general of the island Galbaud du Fort and those of the revolutionary commissioners Léger-Félicité Sonthonax and Étienne Polverel, all the while revolting slaves were getting dangerously close to the city. Taking command of the ships in port,[10] he helplessly witnessed the terrible confusion of the battle of Cap-Français: Galbaud, attempting a coup de force against the commissioners, proclaimed his authority over the Sercey division, consigned him to his quarters, turned his men against him and used his ships to fire the first shots of his attempted insurrection.[11] After two days of bloody street fighting and short-lived success, the governor was forced to take refuge on Jupiter: the embattled commissioners had called on the insurgent slaves, and some ten thousand of them had invested the city, pushing the governor's forces back to shore.[12] Cap-Francais then fell prey to ravaging fires and massacre, with colonists rushing by the thousands towards the port. Sercey succeeded in regaining control of his men, ordered and organized the evacuation,[10] against the orders of the commissioners, and a large convoy of several hundred ships with thousands of colonists on board set sail in the following hours.[13] The admiral then led this makeshift fleet to the mouth of Chesapeake Bay, his wife organising the care of the survivors, receiving for her action among them the nickname of "tutelary angel".[14]

Passing under the authority of Edmond-Charles Genêt, French ambassador to the United States, he was ordered to escort a convoy of American goods bound for the French mainland, but also to carry out an expedition to recapture the Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon archipelago.[13] Setting sail on 9 October, bad weather conditions and the spectre of mutiny forced the ships under Sercey's authority to abandon this latter particularly ambitious objective.[13] He arrived in Brest on 4 November 1793, in the midst of the Reign of Terror, and was arrested on 30 November as a former aristocrat suspected of royalism and a desire to emigrate, then was imprisoned in Luxembourg prison for over a year. Saved from execution by the events of Thermidor 9th, he was reinstated in his rank by the minister Laurent Truguet in January 1795, under the Directory.[3]

In March 1796, a light naval division was formed under his command, composed of the frigates Forte, which flew his flag,[15] Régénérée, Seine, Vertu, and the corvettes Bonne-Citoyenne and Mutine. Its destination was the Isle de France, with 800 men on board under the command of General François-Louis Magallon, an old friend,[16] as well as two commissioners of the Directory, René Gaston Baco de La Chapelle and Étienne Laurent Pierre Burnel, who had been sent to take command of the colony and officially proclaim the Law of 4 February 1794 abolishing slavery.[15] Leaving Rochefort, the division arrived at Port-Nord-Ouest on 18 June 1796. The colonists of the Mascarene Islands immediately welcomed them it with a frigid reception: fearing a situation similar to that of Saint-Domingue, the colonial assembly simply refused to submit to the authority of the commissioners.[17] Wild rumours circulated: it was asserted that Magallon's troops were not there to reinforce the island, but to subdue it. On 21 June, a violent demonstration likely directed by the colonial assembly, with the probable support of Governor Malartic and Admiral Sercey, expelled the Commissioners. They were placed manu militari on a corvette, Moineau, bound for the Spanish Philippines. This lack of support for the men of the Directory, and perhaps this complicity in this seditious turn of events,[18] was reproached to Sercey by minister Truguet, as the rebellion of the Mascarenes was making headlines in Paris. On his return to France, commissioner Baco de La Chapelle published a pamphlet accusing the admiral in vehement terms of having taken part from beginning to end in this expulsion, including of having threatened to sink Moineau should they try to return to land.[19] In her memoirs, Sercey's cousin Félicité de Genlis asserts that the demonstration and expulsion were a "bold manoeuvre" by the Marquis to prevent the commissioners from "revolutionising the colony," which, according to her, "saved it a lot of bloodshed".[20] In any case, he faced no immediate repercussions for his involvement, as he was fiercely and successfully defended in front of the Council of Five Hundred by François-Antoine de Boissy d'Anglas and Joseph Jérôme Siméon,[9] the latter even comparing him to Admiral Pierre André de Suffren and asking for a reward for his actions.[21]

Commerce raiding in the Indian Ocean

However, the Port-Nord-Ouest assembly and Governor Malartic did not behave more warmly once the commissioners were physically removed. With no real resources or capacity to meet the needs of the Sercey division, the colonists urged the admiral to return to sea as soon as possible. On 22 July 1796, after summary repairs and reinforced by the frigate Cybèle,[3] he did so, embarking on a campaign of commerce raiding in the Indian Ocean, with the goal of causing as much harm to enemy trade as possible. He compensated for his limited means by keeping his ships constantly at sea and by operating in the manner of a privateer, financing his supplies through the sale of his numerous catches, notably several East Indiamen taken off the coasts of Ceylon and Sumatra.[22] Planning to attack the Penang trading post, on 8 September 1796 he saw two heavily armed British ships of the line, HMS Arrogant and HMS Victorious, at the entrance of the Strait of Malacca. The next day, he ordered his frigates to attack this superior force, thinking that a confrontation was inevitable.[23] It was a success, and after four hours of fierce fighting, the enemy forces withdrew, leaving the strait and the South China Sea open to Sercey.[24] After many captures, the division docked in Batavia, where it remained for a little more than a month, the counter admiral taking advantage of this rest to negotiate a treaty for the supply of food to the Isle de France.[25]

It was while he was heading back to Port-Nord-Ouest to have this document ratified that the Marquis de Sercey made his greatest tactical error. On 28 January 1797, in the Bali Strait, the Cybèle, which had gone ahead to scout, signalled the presence of a numerically superior enemy. Unable to repair his forces, which were already in bad shape, the admiral erred on the side of caution: when these forces formed a line of battle, he chose to avoid combat and withdrew.[25] He only learned upon arrival at his destination that this enemy force was in fact an annual "China convoy" of the East India Company, including Alfred and Ocean, which, without an escort, had chosen to behave like warships, even going so far as to paint false ports: this display of ingenious tactics by Commodore James Farquharson brought him fame and was greeted with rejoicing by the British press, making frontpages as the Bali Strait Incident.[25] An error of appreciation that was later repeated by another French force in the region, at the battle of Pulo Aura in 1804. For the Sercey division, this terrible missed opportunity marked the beginning of an inexorable decline.[25]

Arriving at the Isle de France in February 1797, though reinforced by the corvette Brûle-Gueule and the frigate Preneuse, issues quickly accumulated: the governor and the colonial assembly were still in no way cooperative, stating that it would no longer be possible to feed the crews of Sercey's ships.[26] The admiral therefore had to base himself temporarily in the Seychelles, not wanting to leave the Mascarenes undefended.[27] Requests for support against British forces abounded, particularly from the Dutch East Indies and from Tipu Sultan, Sultan of Mysore, in addition to the orders of Malartic, who requisitioned the ships for additional missions decided in the absence of Sercey.[28] Without having ever lost a ship in combat, the squadron was reduced to an almost nothing scattered from Mozambique to Java. He set up his command in Surabaya to be closer to the Spanish base in Manila, and a last campaign in the China seas succeeded in taking about forty enemy ships.[29] Desperately awaiting the return of his scattered forces, not knowing that some of them had already been destroyed or captured, he negotiated with the Spanish forces with the aim of continuing his mission, without concrete success: joint offensive attempts were not satisfactory, as in Macao in January 1799. He therefore accepted the evidence and left Java. Returning to Isle de France in May 1799, he succeeded in getting his last ships through an enemy blockade, before repelling British attacks on Port-Nord-Ouest for three weeks.[30] But this was to be the last hurrah of the Sercey division: its last frigate, the last large French ship in the region, Preneuse, was destroyed in Tombeau Bay by HMS Tremendous and HMS Adamant on its return from a raiding campaign off Mozambique on December 11, 1799.[30]

Retirement and role during the Restoration

Admiral Sercey did not return to France until 1802, under the auspices of the Treaty of Amiens. There he found a government entirely different from the one that had given him his orders. He wrote a report explaining his conduct during his years of campaigning, but was met with the hostility of minister Denis Decrès who held him responsible for the fatal outcome of the division of the Indian Ocean. Sercey obtained his retirement on 5 August 1804, was among the first awarded the Legion of Honour by newly-crowned Emperor Napoleon I on 9 December 1804,[31] and then returned to Isle of France, where he settled in Port-Nord-Ouest as a planter.[3] He played an important role in the defence against the invasion of the island by British forces in 1810, being put in command of the forces in the south of the island by General Charles Decaen.[32]

He then sold his properties and returned to France, refusing to live under British rule. Following the first abdication of Napoleon in April 1814, following the Emperor’s defeat in the War of the Sixth Coalition, Sercey was part of the delegation tasked with meeting with King Louis XVIII, then living in exile at Hartwell House, in England. Recalled to service at the Bourbon Restoration, he was made president in May 1814 of a commission mandated by Baron Pierre-Victor Malouët to go to London to organise the release of at least 57,000 prisoners, many of them imprisoned in difficult conditions.[33] Accompanied by the Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Georgette du Buisson de La Boulaye, he was given a sum of 420,000 francs to cover the expenses of transporting and caring for the prisoners[33] and was welcomed at the Court of St James's. He received the oaths of allegiance of French officers to the Bourbon government, and proceeded towards the liberation of the prisoners according to a gradual selection on criteria of personal qualities and loyalty to the monarchy.[34] As a reward, he was promoted to the rank of vice admiral on 28 May 1814[3] and made grand officier of the Legion of Honour in August 1814, then grand-croix of the Order of Saint Louis in May 1816.[3] He enjoyed a good reputation in the circles of power of the Restoration: the Count of Villèle, Prime Minister of Kings Louis XVIII and Charles X from 1822 to 1828, described him in his memoirs as "one of the most distinguished officers of our old Navy".[35] King Charles X later raised him to the rank of grand-croix of the Legion of Honour in October 1828.[3]

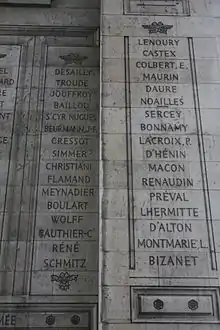

On 7 November 1832, King Louis-Philippe I, with whom he was linked through his cousin the Comtesse de Genlis, the King's tutor who had long remained at his side,[36] finally made him Peer of France. He sat in the Chamber of Peers until his death, voting according to the wishes of the government.[9] His name is inscribed on the west pillar of the Arc de Triomphe.[37]

He died on 10 August 1836 in Paris and was buried in Père-Lachaise Cemetery.[38]

Titles and decorations

Grand-croix of the Legion of Honour (1828[31])

Grand-croix of the Legion of Honour (1828[31]) Grand-croix of the Order of Saint Louis (1816[31])

Grand-croix of the Order of Saint Louis (1816[31])- Peer of France (1832[9])

- Society of the Cincinnati[39]

- Marquess

Bibliography

In English

- Jenkins, Ernest Harol : A History of the French Navy, MacDonald and Jane's, London, 1973.

- Taylor, Stephen (2008). Storm and Conquest: The Battle for the Indian Ocean, 1809. Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-22467-8.

- James, William, The Naval History of Great Britain during the French Revolutionary and Napoleon's wars, volumes 1 and 2, London, 1837, reissue by Conway Maritime Press, London, 2003.

- Popkin, Jeremy D., Facing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian Insurrection, Chicago, Chicago University Press, 2007.

- Humble, Richard, Napoleon's Admirals: Flag Officers of the Arc de Triomphe, 1789–1815, Oxford, Casemate Publishers, 2019.

In French

- Hennequin, Joseph-François-Gabriel, Biographie maritime, ou, Notices historiques sur la vie et les campagnes des marins célèbres français et étrangers, Regnault, Paris, 1836 (read online).

- Guérin, Léon, Histoire Maritime de France, Dufour, Mulat et Boulanger, Paris, 1858 (read online).

- Troude, Onésime, Les Batailles navales de la France, Challamel Ainé, Paris, 1867.

- Robert, Adolphe; Cougny, Gaston, Dictionnaire des parlementaires français depuis le 1er mai 1789 jusqu'au 1er mai 1889, Bourloton, Paris, 1889-1891 (read online).

- Georges Six, Dictionnaire biographique des généraux et amiraux de la Révolution et de l'Empire, Librairie historique et nobiliaire, Paris, 1934 (read online).

- Garneray, Louis, Aventures et Combat, volume 1: Corsaire de la République, Éditions Phébus, Paris, 1985.

- Wanquet, Claude, La France et la première abolition de l'esclavage, 1794-1802, Paris, Éditions Karthala, 1998.

External links

- Digital file in the Léonore database of the French National Archives (in French).

- Biography on the website of the French Senate (in French).

- Biography on the Père-Lachaise Cemetery website (in French).

- Portrait kept at the Paris National Navy Museum (in French).

Citations

- ↑ Drigon de Magny, Claude (1846). Livre d'or de la noblesse de France (in French). Paris: Collège héraldique de France. p. 410.

- 1 2 Hennequin, Joseph-François-Gabriel (1836). Biographie maritime, ou, Notices historiques sur la vie et les campagnes des marins célèbres français et étrangers (in French). Paris: Regnault. p. 191.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Six, Georges (1936). Dictionnaire biographique des généraux et amiraux français de la Révolution et de l'Empire : 1792-1814 (in French). Paris: Librairie historique et nobiliaire. pp. 448–449.

- 1 2 3 Hennequin, p. 192.

- 1 2 Hennequin, p. 193.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hennequin, p. 194.

- 1 2 3 Hennequin, p. 195.

- 1 2 3 4 Hennequin, p. 196.

- 1 2 3 4 Robert and Cougny, p. 303.

- 1 2 3 4 Hennequin, p. 197.

- ↑ Guérin, Léon (1858). Histoire maritime de France (in French). Paris: Dufour. p. 5.

- ↑ Guérin, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 Jacquinet, Charles (1928–1929). Le trafic de la France avec ses colonies pendant les guerres de la Révolution (in French). Paris: École supérieure de guerre navale. p. 62.

- ↑ Guérin, p. 9.

- 1 2 Hennequin, p. 198.

- ↑ Wanquet, Claude (1998). La France et la première abolition de l'esclavage (in French). Paris: Éditions Karthala. p. 344.

- ↑ Gainot, Bernard (2015). L'empire colonial français de Richelieu à Napoléon. (1630-1810) (in French). Paris: Armand Colin. p. 172.

- ↑ Gainot, p. 151.

- ↑ Baco de La Chapelle, René-Gaston (1797–1799). Colonies (in French). Paris: Imprimerie de Baudouin, imprimeur du Corps législatif. pp. 8–9.

- ↑ de Genlis, Stéphanie-Félicité (1868). Mémoires de Madame de Genlis sur la cour, la ville et les salons de Paris (in French). Paris: Typographie Henri Plon. p. 124.

- ↑ Wanquet, p. 446.

- ↑ Guérin, p. 496.

- ↑ Hennequin, p. 204.

- ↑ Guérin, p. 493.

- 1 2 3 4 Humble, Richard (2019). Napoleon's Admirals: Flag Officers of the Arc de Triomphe, 1789–1815. Oxford: Casemate Publishers. p. 43.

- ↑ Guérin, p. 494.

- ↑ Hennequin, p. 206.

- ↑ Hennequin, p. 209

- ↑ Hennequin, p. 209.

- 1 2 Humble, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 "Sercey de, Pierre César Charles Guillaume". Léonore Database. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ↑ d'Epinay, Adrien (1890). Renseignements pour servir à l'histoire de l'Île de France jusqu'à l'année 1810 (in French). Mauritius. p. 396.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 Lutun, Bernard (1992). "1814-1817 ou L'épuration dans la Marine". Revue historique (in French) (July 1992): 63.

- ↑ Le Carvèse, Patrick (2010). "Les prisonniers français en Grande-Bretagne de 1803 à 1814. Étude statistique à partir des archives centrales de la Marine". Napoleonica. La Revue. 8 (2): 8–9.

- ↑ de Villèle, Joseph (1888–1890). Mémoires et correspondance du comte de Villèle (in French). Paris: Librairie académique Didier. p. 143.

- ↑ Castelot, André (1994). Louis-Philippe. Le méconnu (in French). Paris: Perrin. p. 18.

- ↑ Humble, pp. 213-124.

- ↑ Moiroux, Jules (1908). Le cimetière du Père Lachaise (in French). Paris: S. Mercadier. p. 314.

- ↑ Gardiner, Asa Bird (1905). The order of the Cincinnati in France. Newport: The Rhode Island State Society of Cincinnati. p. 191.