Pierre Desceliers (fl. 1537–1553) was a French cartographer of the Renaissance and an eminent member of the Dieppe School of Cartography. He is considered the father of French hydrography.

Little is known of his life. He was probably born at Arques-la-Bataille.[1] The earliest known documentary source for his life places him there as a priest in 1537.[2] Desceliers' father was an archer at the Chateau d’Arques and his family possibly originated from the d’Auge area, where the family name survives between Honfleur and Pont-l’Évêque.[3]

Desceliers was also an examiner of Maritime Pilots and was authorised to award patents on behalf of the French king, as evidenced by the seal found bearing his initials. He probably also taught hydrography. He made a hydrographic chart of the coast of France for Francis, Duke of Guise. Nothing is known of his life after the creation of the 1553 map; the Dictionnaire de biographie française suggests that he died after 1574, but none of its sources support this statement.[4]

Cartographic work

He was close to Jean Ango and Dieppois, explorers Giovanni da Verrazzano and the brothers Jean and Raoul Parmentier. Although it seems unlikely that he took part in any voyages, he was able collect information including portolans, and he incorporated this information into his own maps. A school of cartography formed around him in Dieppe and included Nicolas Desliens among its members.

Desceliers made several large world maps in the style of nautical charts:

- The 1543 world map mentioned in 1872 in the inventory of the collection of Cardinal Louis d'Este under the title The descriptione carta del Mondo in pecorina scritta a mano, miniata tutta per P. Descheliers. The fate of this map is unknown.

- The 1546 world map (2560 × 1260 mm), made to order for Francis I. It later belonged to a certain Jomard, then to the Earl of Crawford and is now stored in England at the John Rylands Library, Manchester (French MS. 1*)

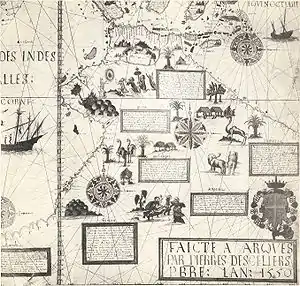

- The 1550 world map (2150 × 1350 mm), made for Henry II, showing his arms as well as those of Anne de Montmorency (Marshal of France) and Admiral Claude d'Annebaut. This chart is preserved in London, at the British Library (Add MS 24065), having been purchased from Cristoforo Negri by the British Museum in 1861.[5][6][7]

- The 1553 world map. This was lost in a fire in Dresden in 1915. A copy is on display in Dieppe Castle. It was displayed at the Exposition internationale de géographie of 1875 in Paris: this has been reported to be another map from 1558,[8] but the catalogue confirms that it was the 1553 map.[9][10]

The Dieppe maps show a precise knowledge of coastlines, and also included representations of imaginary places, fantastic people and bizarre animals. The representation of eastern Canada was well detailed, along with most of the America north and south, just fifty years after the voyage of Columbus. In the southern hemisphere section, a landmass entitled Jave la Grande was shown in the approximate position of Australia. This has led to speculation that the Dieppe maps are evidence of European (possibly Portuguese) exploration of Australia in the 16th century; one hundred years before its well documented exploration by the Dutch.

The image of Java Major on Desceliers' 1550 map was based on the accounts of Marco Polo and Ludovico di Varthema in the Novus Orbis Regionum ac Insularum Veteribus Incognitarum of Simon Grynaeus and Johann Huttich, published in Paris by Antoine Augurelle in 1532. This is made clear by the inscription on the map describing Java. Desceliers' representation of the Southern Continent, titled LA TERRE AVSTRALLE NON DV TOVT DESCOVVERTE (“Terra Australis, recently discovered but not yet fully known”), is derived from Oronce Fine’s 1531 world map, which was also published in 1532 in the Novus Orbis: it bears the same title as given it by Fine in Latin: Terra Australis recenter inventa sed nondum plene cognita (“Terra Australis, recently discovered but not yet fully known”). Desceliers seems to have identified the promontory of Regio Patalis on Fine's Terra Australis with Marco Polo and Ludovico di Varthema's Java Major; hence, his Jave la Grande is an amalgamation of the known north coast of Java with Fine's Regio Patalis.[11]

Despite their great value, both artistic and cartographic, the charts quickly fell into disuse after the end of the 16th century, when the market came to be dominated by Flemish and Dutch mapmakers.

References

- ↑ Anthiaume, Albert (1926). Pierre Desceliers: Père de l'Hydrographie et de la Cartographie Françaises. Rouen: Société «Les Amys du Vieux Dieppe». p. 10.

- ↑ de Robillard de Beaurepaire, Charles (1871). "Recherches sur les établissements d'instruction publique et la population dans l'ancien diocèse de Rouen". Mémoires de la Société des antiquaires de Normandie (in French). 28: 330.

- ↑ Anthiaume, Albert (1916). Cartes marines, constructions navales, voyages de découverte chez les Normands, 1500–1650 (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: Dumont. pp. 78–91.

- ↑ Marouis, F. (1964). Desceliers, Pierre (in French). Vol. 10. Paris: Letouzey et Ané. p. 1247.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ↑ Van Duzer, Chet (2015). The world for a king: Pierre Desceliers' map of 1550. London: The British Library. ISBN 978-0-7123-5618-3.

- ↑ Coote, C. H. (1898). Autotype facsimiles of three mappemondes. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press.

- ↑ Massing, Jean Michel (2003). "La mappemonde de Pierre Desceliers de 1550". In Hervé Oursel; Julia Fritsch (eds.). Henri II et les arts: actes du colloque international, Ecole du Louvre et Musée national de la Renaissance-Ecouen, 25, 26 et 27 septembre 1997. Rencontres de l'Ecole du Louvre (in French). Vol. 15. Paris: Ecole du Louvre. pp. 231–248. ISBN 978-2-904187-08-7.

- ↑ Delisle, Léopold (1902). "Le cartographie dieppois Pierre Desceliers". Journal des sçavans (in French): 674.

- ↑ Fournier, Félix (1875). Congrès international des sciences géographiques, 2eme session, Paris, 1875. Exposition. Catalogue général des produits exposés (in French). Paris: Lahure. p. 157 (section d'Autriche-Hongrie, no. 147).

- ↑ Gaffarel, Paul (1877). "La Découverte du Brésil par les Français". Congrès international des Américanistes (in French). 2 (1): 403.

- ↑ King, Robert J. (3 December 2013). "Havre de Sylla on Jave La Grande". Terrae Incognitae. 45 (1): 30–61. doi:10.1179/0082288413Z.00000000016.