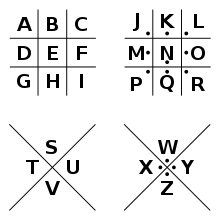

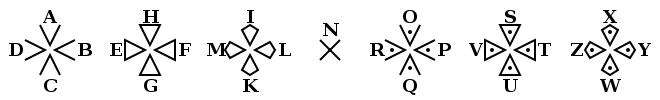

The pigpen cipher (alternatively referred to as the masonic cipher, Freemason's cipher, Rosicrucian cipher, Napoleon cipher, and tic-tac-toe cipher)[2][3] is a geometric simple substitution cipher, which exchanges letters for symbols which are fragments of a grid. The example key shows one way the letters can be assigned to the grid.

Insecurity

The Pigpen cipher offers little cryptographic security. It differentiates itself from other simple monoalphabetic substitution ciphers solely by its use of symbols rather than letters, the use of which fails to assist in curbing cryptanalysis. Additionally, the prominence and recognizability of the Pigpen leads to it being arguably worthless from a security standpoint. Knowledge of Pigpen is so ubiquitous that an interceptor might not need to actually break this cipher at all, but merely decipher it, in the same way that the intended recipient would.

Due to Pigpen's simplicity, it is very often included in children's books on ciphers and secret writing.[4]

History

The cipher is believed to be an ancient cipher[5][6] and is said to have originated with the Hebrew rabbis.[7][8] Thompson writes that, “there is evidence that suggests that the Knights Templar utilized a pig-pen cipher” during the Christian Crusades.[9][10]

Parrangan & Parrangan write that it was used by an individual, who may have been a Mason, “in the 16th century to save his personal notes.”[11]

In 1531 Cornelius Agrippa described an early form of the Rosicrucian cipher, which he attributes to an existing Jewish Kabbalistic tradition.[12] This system, called "The Kabbalah of the Nine Chambers" by later authors, used the Hebrew alphabet rather than the Latin alphabet, and was used for religious symbolism rather than for any apparent cryptological purpose.[13]

On the 7th July 1730, a French Pirate named Olivier Levasseur threw out a scrap of paper written in the pigpen cipher, allegedly containing the whereabouts of his treasure which was never found but is speculated to be located in Seychelles. The exact configuration of the cipher has also not been determined, an example of using different letters in different sections to further complicate the cipher from its standard configuration.

Variations of this cipher were used by both the Rosicrucian brotherhood[14] and the Freemasons, though the latter used the pigpen cipher so often that the system is frequently called the Freemason's cipher. Hysin claims it was invented by Freemasons.[15] They began using it in the early 18th century to keep their records of history and rites private, and for correspondence between lodge leaders.[3][16][17] Tombstones of Freemasons can also be found which use the system as part of the engravings. One of the earliest stones in Trinity Church Cemetery in New York City, which opened in 1697, contains a cipher of this type which deciphers to "Remember death" (cf. "memento mori").

George Washington's army had documentation about the system, with a much more randomized form of the alphabet. During the American Civil War, the system was used by Union prisoners in Confederate prisons.[14]

Example

Using the Pigpen cipher key shown in the example above, the message "X marks the spot

" is rendered in ciphertext as

Variants

The core elements of this system are the grid and dots. Some systems use the X's, but even these can be rearranged. One commonly used method orders the symbols as shown in the above image: grid, grid, X, X. Another commonly used system orders the symbols as grid, X, grid, X. Another is grid, grid, grid, with each cell having a letter of the alphabet, and the last one having an "&" character. Letters from the first grid have no dot, letters from the second each have one dot, and letters from the third each have two dots. Another variation of this last one is called the Newark Cipher, which instead of dots uses one to three short lines which may be projecting in any length or orientation. This gives the illusion of a larger number of different characters than actually exist.[18]

Another system, used by the Rosicrucians in the 17th century, used a single grid of nine cells, and 1 to 3 dots in each cell or "pen". So ABC would be in the top left pen, followed by DEF and GHI on the first line, then groups of JKL MNO PQR on the second, and STU VWX YZ on the third.[2][14] When enciphered, the location of the dot in each symbol (left, center, or right), would indicate which letter in that pen was represented.[1][14] More difficult systems use a non-standard form of the alphabet, such as writing it backwards in the grid, up and down in the columns,[4] or a completely randomized set of letters.

The Templar cipher is a method claimed to have been used by the Knights Templar and uses a variant of a Maltese Cross.[19] This is likely a cipher used by the Neo-Templars (Freemasons) of the 18th century, and not that of the religious order of the Knights Templar from the 12th-14th centuries during the Crusades.[20]

Notes

- 1 2 Wrixon, pp. 182–183

- 1 2 Barker, p. 40

- 1 2 Wrixon, p. 27

- 1 2 Gardner

- ↑ Bauer, Friedrich L. "Encryption Steps: Simple Substitution." Decrypted Secrets: Methods and Maxims of Cryptology (2007): 43.

- ↑ Newby, Peter. "Maggie Had A Little Pigpen." Word Ways 24.2 (1991): 13.

- ↑ Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna. The Theosophical Glossary. Theosophical Publishing Society, 1892, p. 230

- ↑ Mathers, SL MacGregor. The Kabbalah Unveiled. Routledge, 2017, p. 10

- ↑ Thompson, Dave. "Elliptic Curve Cryptography." (2016)

- ↑ MacNulty, W. K. (2006). Freemasonry: symbols, secrets, significance. London: Thames & Hudson, p. 269

- ↑ Parrangan, Dwijayanto G., and Theofilus Parrangan. "New Simple Algorithm for Detecting the Meaning of Pigpen Chiper Boy Scout (“Pramuka”)." International Journal of Signal Processing, Image Processing and Pattern Recognition 6.5 (2013): 305–314.

- ↑ Agrippa, Henry Cornelius. "Three Books of Occult Philosophy, or of." JF (London, Gregory Moule, 1650) (1997): 14–15.

- ↑ Agrippa, Cornelius. "Three Books of Occult Philosophy", http://www.esotericarchives.com/agrippa/agripp3c.htm#chap30

- 1 2 3 4 Pratt, pp. 142–143

- ↑ Hynson, Colin. "Codes and ciphers." 5 to 7 Educator 2006.14 (2006): v–vi.

- ↑ Kahn, 1967, p.~772

- ↑ Newton, 1998, p. 113

- ↑ Glossary of Cryptography

- ↑ McKeown, Trevor W. "Purported Templars cipher". freemasonry.bcy.ca. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ Guénon, René (2004). Studies in Freemasonry and the Compagnonnage. Translated by Fohr, Henry D.; Bethell, Cecil; Allen, Michael. Sophia Perennis. p. 237. ISBN 978-0900588518.

References

- Barker, Wayne G., ed. (1978). The History of Codes and Ciphers in the United States Prior to World War I. Aegean Park Press. ISBN 0-89412-026-3.

- Gardner, Martin (1972). Codes, ciphers and secret writing. Courier Corporation. ISBN 0-486-24761-9.

- Kahn, David (1967). The Codebreakers. The Story of Secret Writing. Macmillan.

- Kahn, David (1996). The Codebreakers. The Story of Secret Writing. Scribner. ISBN 0-684-83130-9.

- Newton, David E. (1998). "Freemason's Cipher". Encyclopedia of Cryptology. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 0-87436-772-7.

- Pratt, Fletcher (1939). Secret and Urgent: The story of codes and ciphers. Aegean Park Press. ISBN 0-89412-261-4.

- Shulman, David; Weintraub, Joseph (1961). A glossary of cryptography. Crypto Press. p. 44.

- Wrixon, Fred B. (1998). Codes, Ciphers, and other Cryptic & Clandestine Communication. Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, Inc. ISBN 1-57912-040-7.

External links

- Online Pigpen cipher tool for enciphering small messages.

- Online Pigpen cipher tool for deciphering small messages.

- Cipher Code True Type Font

- Deciphering An Ominous Cryptogram on a Manhattan Tomb presents a Pigpen cipher variant

- Elian script-often considered a variant of Pigpen.