| Pillar Point Bluff | |

|---|---|

Pillar Point Bluff facing southwest | |

| |

| Type | Park |

| Location | 840 Airport St. Moss Beach, California, 94038. United States |

| Coordinates | 37°30′26″N 122°30′10″W / 37.50722°N 122.50278°W |

| Area | 220 acres (0.89 km2) |

| Owned by | San Mateo County |

| Operated by | San Mateo County Parks Department |

| Open | All year; sunrise to sunset |

| Public transit access | samTrans 117,294 |

| Website | www |

Pillar Point Bluff is a 220-acre park in San Mateo County, California. It is part of the Fitzgerald Marine Reserve, owned by the U.S. state of California, and managed by San Mateo County as a county park and nature preserve. The park is located between Princeton-by-the-Sea and Moss Beach, just north of the Pillar Point peninsula, Pillar Point Harbor, and Half Moon Bay. The area was inhabited by coastal indigenous peoples for thousands of years, and in recent centuries, was used for livestock grazing by Spanish Missions and Mexican ranchos. Pillar Point Bluff was once part of the Rancho Corral de Tierra Mexican land grant before California became a state.

Peninsula Open Space Trust first purchased the land in large parcels from 2004 to 2008 to protect it from development, selling it to the county for use as a park in 2011. Additional parcels were added in 2015. The land is now part of the 1,200-mile (1,900 km) California Coastal Trail, a network of public trails along the entire coast of California. The park offers trails for hiking, jogging, horseback riding, cycling and on-leash dog walking. The trails wind through a coastal scrub and coastal terrace prairie habitat, with scenic views of wetlands, farmlands, the Montara Mountain, Half Moon Bay, the Pacific Ocean, Mavericks surf break, and native wildlife, including seasonal views of wildflowers and gray and humpback whales. The area is also home to the threatened California red-legged frog and the endangered San Francisco garter snake. The Jean Lauer Trail, a dirt-packed hiking trail, is ADA accessible.

Geography

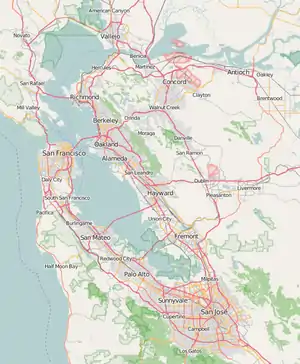

Pillar Point Bluff is a San Mateo County park located between Moss Beach and Princeton-by-the-Sea, approximately 20 miles (32 km) south of San Francisco and 50 miles (80 km) north of Santa Cruz. The 220-acre (0.89 km2) park[1] is located in the westernmost area of Moss Beach, extending along the bluff top with 170-foot (52 m) cliffs that drop down to the Pacific Ocean in the west.[2] Its boundaries lie from Bernal Avenue in the north to the community of Princeton-by-the-Sea in the south, bounded by the Pillar Ridge private community and Airport Street in the east.[3]

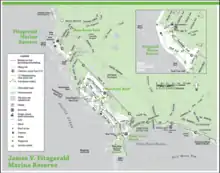

The park is part of the greater Fitzgerald Marine Reserve, which in turn is part of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. The reserve is jointly managed by San Mateo County Parks and Recreation and the California Department of Fish and Game. It contains both the intertidal marine habitats below Pillar Point Bluff and the coastal bluffs themselves. The reserve is approximately 402 acres in total size, encompassing three miles in distance from Point Montara to Pillar Point, while also stretching 1,000 feet into the Pacific Ocean.[4] Ross' Cove, the beach directly below Pillar Point Bluff, is a part of the Montara State Marine Reserve,[1] while the Pillar Point State Marine Conservation Area overlaps and encompasses the area towards the end of the peninsula.[5]

The large, white radome of the Pillar Point Air Force Station can be seen in the southernmost part of the peninsula overlooking the promontory, with views of Half Moon Bay and Pillar Point Harbor to the south.[6] Towards the east, views of the Half Moon Bay Airport,[7] farmlands, Rancho Corral de Tierra (a part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area), and Montara Mountain can be seen from the bluff trails.[3] To the west, one can see the Pacific Ocean and Mavericks surf break.[6]

Geology

The San Gregorio Fault, an active, 209 km (130 mi) long coastal fault, is located mostly offshore of Northern California. In that area, it comes onshore in only two points, between Año Nuevo Point and San Gregorio, and between Pillar Point and Moss Beach.[8] The northern, on-land portion of the fault at Pillar Point forms a 30 m high, east-facing escarpment to the east of Pillar Point Bluff. The fault cuts across land along the southern side of Pillar Point Bluff towards the northern end, and to the west of the San Andreas Fault. This portion of the San Gregorio Fault is classified as an active, late Holocene, strike-slip fault, and was believed to be active sometime after 1270 CE but before 1775 CE. Before the park was created, Pillar Point Bluff was referred to as Seal Cove Bluffs, and the onshore portion of the San Gregorio Fault in this area was sometimes referred to as the Seal Cove Fault in the geological literature.[8] The sedimentary rocks in the bluff are classified as part of the Purisima Formation, from the late Miocene or early Pliocene.[9] Malacologists identified marine invertebrate fossils from the Seal Cove and Pillar Point Bluff area consisting predominantly of species of butter clam (Saxidomus gigantea) and the Pacific littleneck clam (Leukoma staminea).[10]

History

Evidence suggests that the three-mile long area from Moss Beach to Pillar Point was likely inhabited sometime around 6,000–7,000 years ago, with coastal indigenous peoples gathering seafood from the offshore reefs, while also hunting rabbits, deer, and hauled-out harbor seals from the surrounding land.[11] In the pre-Columbian era, the Chiguan Ohlones inhabited the area,[lower-greek 1] living in two major villages near the coast, Ssatumnumo, which is now present-day Princeton-by-the-Sea, and Chagunte, which is thought to have been near or around Pillar Point.[12]

On October 30, 1769, the Portolá expedition famously described Pillar Point as it camped near Martini Creek at the bottom of Montara Mountain. Franciscan padre Juan Crespí, the official diarist, wrote: "The coast and mainland at about a league from this stream form a very long point of land reaching far out to sea, and a great deal of flats running along its tip, with many large rocks seeming from afar to be island rocks."[13] Crespí named the point "punta del Ángel Custodio", or "Guardian Angel Point".[14] The expedition continued north, making the first recorded European sighting of San Francisco Bay just a few days later, on November 1.[15]

Spain eventually colonized the area, establishing Mission San Francisco de Asís in 1776, just five days before the signing of the Declaration of Independence. By the early 1790s, the Mission was using the area near Pillar Point for horse and cattle grazing, where it was described as El Pilar or Los Pilares, based on the rocky formation near the promontory.[16] These types of natural enclosures for livestock at Pillar Point were referred to as "El Corral de Tierra" (the Earth Corral).[17] The land became part of Mexico after they achieved their independence in 1821. The Mexican secularization act of 1833 granted the land, then known as Rancho Corral de Tierra, in two parcels. The Mexican–American War took place from 1846 to 1848, leading to Mexico ceding the area to the United States, making it part of the thirty-first state of California in 1850.[18]

By the mid-19th century, Portuguese immigrants from the Azores ran a shore whaling station at Pillar Point, using the bluff to spot whales and then launch boats to capture them. On average, a single shore whaling station in California would harvest 180 whales per year. The station hauled the whale carcasses onto the reefs at Pillar Point, where they would strip the blubber to extract the oil. This continued for approximately 40 years, declining as petroleum oil slowly replaced it.[19] By the 1890s, commercial agriculture began to take off, with artichokes being grown south of the bluffs in El Grenada. In the early 20th century, shore whaling had died out, but a dairy farm was now in operation at the base of the bluffs.[20] In the 1920s and 1930s, the beach and cliff area just north of the bluffs was used by rum-runners to ship and distribute illegal whiskey during the Prohibition era.[21] Ranching continued up until World War II, when the southernmost part of the peninsula was converted into the Pillar Point Military Reservation to protect the coast from the potential threat of attack from Japan.[22] To the south of the bluffs, the basic infrastructure of Pillar Point Harbor was completed in the 1960s.[23]

Background

The coastal area to the north, around Seal Cove, faced major threats and environmental destruction from human encroachment until it was protected in November 1969 as the Fitzgerald Marine Reserve.[24] In 1972, Congress passed the Coastal Zone Management Act to encourage coastal states to develop and implement coastal zone management plans. The California Coastal Act of 1976 (Ca. Pub. Res. Code § 30000) permanently created the California Coastal Commission, an independent state agency tasked with coastal zone management.[25] The Coastal Act requires that local coastal programs for each county implement its requirements, particularly the policies in Chapter 3 stipulating public access and recreation.[26] San Mateo County Parks began to develop a long-term plan for connecting trails along the coast.[3]

The California State Legislature passed Senate Bill 908 in 2001, authorizing the Coastal Conservancy to complete a report on a proposal to build a network of state-wide, public trails along the entire coast of California, to both increase public access to the coastline and educate visitors about the environmental resources of the state. Concurrently, the Fitzgerald Marine Master Plan was completed in 2002. The reserve, which is part of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, includes 32 acres (0.13 km2) of upland coastal bluffs in their master plan.[27]

Soon after, the Coastal Conservancy published Completing the California Coastal Trail in 2003. The report makes the case for restoring and protecting the coastal lands of California and creating a network of public trails open to everyone, "a continuous public right-of-way along the California coastline designed to foster appreciation and stewardship of the scenic and natural resources of the coast through hiking and other complementary modes of non-motorized transportation."[27] The report specified certain conditions, highlighting the need for a new trail in an area of the Fitzgerald Marine Reserve facing the land, leading the Coastal Conservancy to eventually grant funds to Peninsula Open Space Trust (POST), a private nonprofit with a mandate to protect and preserve natural areas of the state from development, to begin planning new trails and infrastructure for a proposed park at Pillar Point Bluff.[28]

Establishment

Before becoming a park, Pillar Point Bluff faced pressure by commercial developers for decades, beginning in the later part of the 20th century.[29] Although multiple sections of the bluff remained in private hands during this time and were owned by different parties, the land was still used by the public for recreation, with people creating trails over the years through repeated wear and tear on the grassy bluff.[30] Investors and absentee landowners proposed building golf courses, new houses, bed-and-breakfasts, hotels, and even a business park, but none were approved.[31]

With no guarantee that any part of the land would remain an open space, and with an interest in using the bluff as a future node for the California Coastal Trail, POST acquired the land from private property owners in stages over about a decade. From 2004 to 2015, POST negotiated and purchased approximately 161 acres (0.65 km2) in four separate parcels for a proposed county park. Funding was provided by donors such as the Coastal Conservancy and the Living Landscape Initiative of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.[32]

As POST started acquiring the private property, inspections discovered it was threatened by erosion and covered in non-native, invasive Cape ivy (Delairea odorata)[33] from South Africa and pampas grass (Cortaderia jubata) from South America, limiting the potential biodiversity of the area.[34] It is believed that pampas grass got a foothold on the bluff due to its previous widespread use in California landscaping.[35] POST began habitat restoration efforts in 2005,[2] spending that summer clearing out pampas grass by the roots, allowing native plants and animals to return, and removing obstacles to the ocean views.[34] To help prevent erosion, POST improved drainage,[36] moved old hiking paths from slopes that were eroding to new trails, and planted native plants on denuded areas of the bluff.[37] POST also removed the remains of the old dairy structure, restored irrigation ponds for wildlife use,[38] and built a ten-car parking lot and restrooms.[30]

San Mateo County purchased the land from POST in August 2011 with a $3 million grant from the Wildlife Conservation Board, adding it to the James V. Fitzgerald Marine Reserve.[39] Pillar Point Bluff is now part of the California Coastal Trail, a network of trails along the 1,200-mile (1,900 km) California coastline. It connects with the Dardenelle Trail in the north and the Half Moon Bay Coastal Trail in the south.[lower-greek 2]

Ecology

Ecoregions

Pillar Point Bluff is a local biological hotspot, home to a rare coastal scrub and coastal terrace prairie habitats. The area is surrounded at its base by Pillar Point Marsh in the southeast, a system of vegetated wetlands and intertidal flats. The salt marsh is composed of decomposing plants in a hypoxic environment, providing habitats for invertebrates, fish, and birds. The marsh also helps to mitigate coastal erosion by absorbing wave energy.[41]

Wildlife

A 2000 survey of species in the general area counted five types of amphibians, 14 types of reptiles, 94 types of birds, and 32 types of mammals. The habitat features rare wildlife species like the California red-legged frog and the San Francisco garter snake.[42] The Western pond turtle may be found in the area around the ocean. Cottontail rabbits are frequently seen on the bluff trails.[43] Birds in the habitat range from songbirds like the salt marsh common yellowthroat, to cormorants, red-tailed hawks,[43] pelicans, egrets, and pigeon guillemots.[43] Hikers may view harbor seals below the bluff on the beaches and in the ocean.[43] In the spring, gray whales are visible, while in the summer and fall, humpback whales can be spotted in the ocean from the bluffs. Native plants[lower-greek 3] include sticky monkey-flower, rushes, coyote brush,[34] coffeeberry, toyon, and buckwheat. Other plants found growing in the Pillar Point coastal habitat include knotweed, California saltbush, chocolate lily, and coastal gumplant.[44]

Since 2014, citizen scientists have attempted to record all of the living species within the Pillar Point Bluff area using the iNaturalist platform.[45] To date, 296 species have been confirmed, of which 285 species have been directly observed from the bluff and trails, including 124 different plants, 85 types of birds, 30, insects, 11 molluscs, 5 mammals, 9 fungi and lichens, 4 reptiles, and 2 amphibians, among many others.[46]

Threats

Threats to Pillar Point Bluff include invasive species, erosion, and off-leash dogs.[47] Invasive plants like pampas grass (Cortaderia jubata) and oxalis (Oxalis pes-caprae) threaten the Pillar Point Bluff ecosystem and are routinely monitored for eradication. Efforts to control the pampas grass population have been largely successful since the park was established, but maintenance and control of invasive oaxlis is ongoing.[48] Brush removal efforts target trees like Monterey pines (Pinus radiata), which can contribute to wildfires and prevent native plants from growing in the coastal habitat.[49]

Erosion is a continuing threat to the bluff and the trails. Hazard assessments report that protective coastal sand and beaches have declined during the last four decades. The bluffs are persistently threatened with cracks, fissures, rockfalls, and landslides due to increasing rates of coastal retreat, with Pillar Point Bluff retreating at an estimated 1.5 feet (0.46 m) per year.[50] Just outside the park, along the southernmost side of Pillar Point, the West Trail Shoreline Protection project relies on a living shoreline instead of a seawall solution, complete with elevated sand dunes as a dynamic revetment and underwater rocks to distribute sand.[51]

Off-leash dogs have also been a topic of concern, due to their potential for wildlife and habitat destruction. Dogs can pose a threat to small animals who live in burrows on the bluffs as well as harbor seal pups on the beaches below.[52]

Recreation

The park offers self-guided nature trails for hikers, joggers, equestrians, cyclists and on-leash dog walkers. Trail views include summer wildflowers, the Pacific Ocean, and Mavericks surf break (binoculars are recommended).[43] The main entrance to the park is located at 840 Airport Street.[43] Restrooms are available at both the main entrance on Airport Street and at the Fitzgerald Marine Reserve trailhead entrance on California Avenue. The major trails are dirt, but the Jean Lauer Trail is wheelchair accessible.[53]

There are four main trails within the park with multiple variations possible depending on the route. Pillar Point Bluff Trail begins at Airport Street (marker 7) and connects to the Jean Lauer Trail and Frenchman's Reefs Trail.[54] Jean Lauer Trail is an ADA accessible dirt path along the top of the bluff that is accessed from the Airport Street parking lot and connects to the 1 Alvarado Avenue intersection with Bernal Avenue (marker 1).[55] The trail is named after a former employee of Peninsula Open Space Trust (POST).[56] Ross' Cove Trail connects to the Jean Lauer Trail on the bluff and also leads down to the beach.[57] Frenchman's Reefs Trail connects to the Jean Lauer Trail and Pillar Point Bluff Trail,[58] as well as to the end of Bernal Avenue (trail marker 4), which has very limited parking.[6]

For longer hikes, visitors can start at the main entrance (marker 7), in the south from the West Shoreline access trailhead (marker 15), or well outside the park in the north from the Fitzgerald Marine Reserve trailhead.[54] From the West Shoreline trailhead, start at trail marker 15. The southwest entrance is found near the Pillar Point Marsh, at 22 West Point Avenue, near the Pillar Point Harbor, in the West Shoreline access parking lot. From this direction, the trailhead is accessed by a paved service road which begins behind a yellow gate across the street from the parking lot. Looping back around from marker 15 through 13, 12, 9, and 2, depending on the chosen route back to 15, the trail is approximately 2.5 miles (4.0 km) long round-trip.[6] For a longer hike that starts at the main entrance and goes all the way to the Fitzgerald Marine Reserve trailhead and loops back, begin at the main entrance to Pillar Point Bluff park, connect to the Bernal Avenue trailhead (trail markers 1 and 4 above), leave the park altogether and head towards Ocean Boulevard in the direction of Seal Cove, follow Beach Way and then Cypress Avenue, until the trailhead entrance is reached at the Fitzgerald Marine Reserve at North Lake Street and California Avenue (see Fitzgerald Marine Reserve map for trail details). The trail is approximately 4.5 miles (7.2 km) round-trip.[59]

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ Hylkema 1991, p. 54: According to Mission register data the Chiguan were one of six tribelet groups in the general area. This includes the Cotegen of Purisima Creek, the Oljon of San Gregorio Creek, the Quiroste of Ano Nuevo, the Cotoni of Scott Creek, and the Uypin of Santa Cruz. A smaller group known as the Guemelento or Wemelente lived in the upper Pescadero Creek area.

- ↑ See the Fitzgerald Marine Reserve map and brochure for details of connecting routes.

- ↑ Botanists collected specimens in the area of the Santa Cruz Mountains for centuries, but these were held in mostly private collections until the mid-20th century. Stanford botanist John Hunter Thomas surveyed the vascular plants in the Pillar Point area in the late 1950s and published his work in 1961.

References

- 1 2 Davidson 2023.

- 1 2 Duwe & Nowak 2008, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 Weigel 2016.

- ↑ Postel et al. 2010b, pp. 185-186.

- ↑ Ochavillo 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Mullally & Mullally 2017, pp. 122–125.

- ↑ Murtagh 2011.

- 1 2 Simpson et al. 1997.

- ↑ Pampeyan 1994, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Kennedy 1981, p. 11-12.

- ↑ Svanevik & Burgett 2001, p. 47.

- ↑ Department of Parks and Recreation 2018, p. 8; Gerber et al. 2009, p. 5.9.

- ↑ Neely 2019, p. 379.

- ↑ Department of Parks and Recreation 2018, p. 4.

- ↑ Alexander & Hamm 1916, p. 15.

- ↑ Hoover et al 2002. p. 394.

- ↑ Gudde 1998, p. 92.

- ↑ TetraTech 2012, p. 3-8.

- ↑ Postel et al. 2010b, pp. 145–155.

- ↑ Davidson & Duwe 2011, p. 5.

- ↑ Postel et al. 2010b, pp.139–140, 168.

- ↑ Gerber et al. 2009, p. 2.3, 5.10, 6.1–2.

- ↑ Postel et al. 2010a, p. 5

- ↑ Svanevik & Burgett 2001, pp. 47–51.

- ↑ National Park Service 2011, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ County of San Mateo 2022.

- 1 2 National Park Service 2011, p. 118, 120–121.

- ↑ California Coastal Commission 2015, p. 8.

- ↑ Weigel 2015.

- 1 2 Noack 2008.

- ↑ Half Moon Bay Review 2011; Weigel 2015.

- ↑ Weigel 2015.

- ↑ Muscarella & Cavalli 2004, pp. 3-5.

- 1 2 3 Sharman & Nowak 2005, p. 6.

- ↑ Duwe & Nowak 2008, p. 7.

- ↑ Nowak 2009, p. 7.

- ↑ Davidson & Duwe 2011, p. 4.

- ↑ San Mateo Daily Journal 2017.

- ↑ Davidson & Duwe 2011, pp. 4–5; Associated Press 2011.

- ↑ Nowak 2006, p. 5.

- ↑ San Mateo County Parks 2023.

- ↑ Potter 2013, pp. 711–712.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Scott 2011.

- ↑ Thomas 1961, p. 147, 150, pp. 118–119, 347.

- ↑ Mellon et al. 2014, p. 5.

- ↑ iNaturalist 2023.

- ↑ Lopez 2022.

- ↑ Faul 2023.

- ↑ Tokofsky 2023.

- ↑ Reis 2016.

- ↑ Howell 2021.

- ↑ Roberts 2021.

- ↑ California Coastal Commission 2014, pp. 146–147.

- 1 2 Salcedo 2016, pp. 208–213.

- ↑ California Coastal Conservancy 2007, pp. 3, 14, 22, 82.

- ↑ Fox 2020.

- ↑ Davidson 2023; San Mateo County Parks Department 2021, pp. 4, 5, 7, 9.

- ↑ Pillar Point Bluff Self-Guided Tour 2023, p. 1.

- ↑ Hamilton 2018, p. 133; Salcedo 2016, pp. 208–213.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Philip W.; Hamm, Charles P. (1916). History of San Mateo County. Press of Burlingame Publishing Co. OCLC 20578055.

- Associated Press. (August 17, 2011). "San Mateo County purchases scenic bluff". In AP Regional State Report – California.

- Ballard, Hannah; Hylkema, Mark (August 2013). "Appendix E: Natural, Cultural, and Scenic Resources Planning and Analysis Reports". In Cultural Resources: Existing Conditions Report for the Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District Vision Plan. Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District.

- Calderon, Nicholas; Baas, John (October 28, 2021). "The Off-Leash Dog Recreation Pilot Program at Pillar Point Bluff and Quarry Park". Final Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration. San Mateo County Parks Department. WRA, Inc.

- California Coastal Conservancy (2007). "Staff recommendation, May 24, 2007: Pillar Point Bluff Coastal Trail Project". UC Riverside, Library, Water Resources Collections and Archives. Coastal Conservancy and related aquatic resources documentation. Calisphere. California Digital Library (CDL).

- California Coastal Commission (2014). California Coastal Access Guide. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520278172. OCLC 900006907

- California Coastal Conservancy (2015). "Staff recommendation, January 29, 2015: Pillar Point Bluff (Thompson) Acquisition. Project No. 14-049-01. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- "County folds Pillar Point bluff into Fitzgerald Marine Reserve". Half Moon Bay Review. Aug 18, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- County of San Mateo. (March 27, 2020). "San Mateo County Parks Closes All Parks to Slow the Spread of COVID-19". County of San Mateo Joint Information Center. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- County of San Mateo. (October 12, 2022). "Consideration of a Coastal Development Permit to construct public access improvements at Tunitas Creek Beach County Park in the unincorporated San Gregorio area of San Mateo County." Planning and Building Department. San Mateo County Parks Department.

- Davidson, Kate Cheney; Duwe, Ann (Fall 2011). "POST Transfers Pillar Point Bluff". Landscapes. Peninsula Open Space Trust. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- Davidson, Ben (July 9, 2023). "Discovering the Bay Area's hidden beaches from Half Moon Bay to Point Reyes". The Mercury News. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- Department of Parks and Recreation. (September 2013). "Montara Mountain CHL DRAFT". Portolá Expedition Camp, CHL No. 25. State of California. Natural Resources Agency.

- Duwe, Ann; Nowak, Nina (Winter 2008). Trailblazing at Pillar Point Bluff". Landscapes. Peninsula Open Space Trust. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- Faul, Samantha (2023). "Invasive Plant Management at Pillar Point Bluff". San Mateo County Parks. County of San Mateo. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- Fox, Zionne (December 24, 2020). "Our Favorite Wheelchair Accessible & Easy Access Trails". Field Notes Blog. Peninsula Open Space Trust. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- Gerber, Joyce L.; Price, Barry A.; Lebow, Clayton G.; Galoian, Mary Clark (April 2009). "Cultural Resources Management Plan for Pillar Point Air Force Station San Mateo County, California". Applied EarthWorks, Inc. Report submitted to the U.S. Air Force.

- Gudde, Erwin Gustav (1998). California Place Names: The Origin and Etymology of Current Geographical Names. (4th ed. Rev. by William Bright). University of California Press. ISBN 0520213165. OCLC 37854320.

- Hamilton, Linda. (2018). Hiking the San Francisco Bay Area: A Guide to the Bay Area's Greatest Hiking Adventures. Falcon Guides. ISBN 9781493029839. OCLC 1002831184.

- Hoover, Mildred Brooke; Rensch, Hero Eugene; Rensch, Ethel Grace; Abeloe, William N. (2002). Historic Spots in California. (5th ed. Rev. by Douglas E. Kyle). Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804744829. OCLC 50735628.

- Howell, August (September 8, 2021). "Harbor District approves 'living shoreline' bid". Half Moon Bay Review. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- Hylkema, Mark Gerald (1991). "Prehistoric native American adaptations along the central California coast of San Mateo and Santa Cruz counties". Master's Theses. San Jose State University. 131. doi:10.31979/etd.qke6-ss3e.

- Kennedy, G.L., Lajoie, K.R., Blunt, D.J.; Mathieson, S.A. (June 1981). "The Half Moon Bay terrace, San Mateo County, California, and the age of its Pleistocene invertebrate faunas". Annual Report of the Western Society of Malacologists. v. 14. ISSN 0361-1175. OCLC 499477494.

- Koehler, R. D., R. C. Witter, G. D. Simpson, E. Hemphill-Haley, and W. R. Lettis (2005). "Paleoseismic investigation of the northern San Gregorio fault, Half Moon Bay, California". Final Technical Report, U.S. Geological Survey National Earthquake Hazards Reduction Program, Award No. 04HQGR0045.

- Lopez, Sierra (February 10, 2022). "San Mateo County keeps dogs leashed". San Mateo Daily Journal. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- Mellon, Michelle; Scott, Julia; von Kaene, Manon (Fall 2014). "Honoring our Local Wilderness". Landscapes. Peninsula Open Space Trust. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- Moffitt, Mike (April 29, 2020). "San Mateo County to reopen 13 parks". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Mullally, Linda; Mullally, David (2017). Coastal Trails of Northern California: Including Best Dog Friendly Beaches. Falcon Guides. ISBN 9781493026043. OCLC 985447176.

- Murtagh, Heather (September 3, 2011). "End summer with a hike". San Mateo Daily Journal. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- Muscarella, Kendra; Cavalli, Gary (Winter 2004). "Annual Report 2004". Landscapes. Peninsula Open Space Trust. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- Neely, Nick (2019). Alta California: From San Diego to San Francisco, A Journey on Foot to Rediscover the Golden State. Counterpoint. ISBN 9781640091665. OCLC 1113895977.

- Noack, Mark (August 20, 2008). "Coastal Trail gets four-mile expansion". Half Moon Bay Review. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- Noack, Mark (January 22, 2015). "Land trust looks to lock in bluffs". Half Moon Bay Review. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- National Park Service (2011). "Golden Gate National Recreation Area, Muir Woods National Monument: Draft General Management Plan, Environmental Impact Statement". Vol. III. U.S. Department of the Interior.

- Nowak, Nina (Winter 2006). "Annual Report 2006". Landscapes. Peninsula Open Space Trust. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- Nowak, Nina (Winter 2009). "Annual Report 2009". Landscapes. Peninsula Open Space Trust. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- Ochavillo, Vanessa (January 6, 2021). "Locals say sea life at risk over Pillar Point harvesting". Half Moon Bay Review. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- Pampeyan, Earl H. (1994). "Geologic map of the Montara Mountain and San Mateo 7-1/2' quadrangles, San Mateo County, California". IMAP 2390. U.S. Geological Survey. U.S. Department of the Interior. doi:10.3133/i2390.

- "Pillar Point Bluff". iNaturalist. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- "Pillar Point Bluff Self-Guided Tour". San Mateo County Parks. February 2023. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- Pillar Point State Marine Conservation Area. Map. Facts, Map & Regulations. California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- "POST transfers 140-acre Pillar Point Bluff to county". San Mateo Daily Journal. August 16, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- Postel, Mitch; Haller, Stephen; Davis, Lee (2010a). "Introduction". Historic Resource Study for Golden Gate National Recreation Area in San Mateo County. National Park Service. San Francisco State University. San Mateo County Historical Association.

- Postel, Mitch; Haller, Stephen; Davis, Lee (2010b). "Rancho Coral de Tierra (and the Montara Lighthouse Station)". Historic Resource Study for Golden Gate National Recreation Area in San Mateo County. National Park Service. San Francisco State University. San Mateo County Historical Association.

- Potter, Christopher (2013). "Ten years of land cover change on the California coast detected using Landsat satellite image analysis: Part 2—San Mateo and Santa Cruz counties". Journal of Coastal Conservation. ISSN 1400-0350. doi:10.1007/s11852-013-0270-3.

- Reis, Julia (July 20, 2016). "Report: 'Especially damaging' erosion at Pillar Point". Half Moon Bay Review. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- Roberts, Lennie (October 25, 2021). "Speaking Up for Wildlife at Pillar Point Bluff". Green Foothills Foundation. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- Salcedo, Tracy (2016). Hiking through History: San Francisco. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781493017973.

- Scott, Julia (August 16, 2011). "San Mateo County buys Pillar Point Bluff from open space group". San Mateo County Times. Retrieved October 28, 2023.

- Sharman, Anne; Nowak, Nina (Winter 2005). "Annual Report 2005". Landscapes. Peninsula Open Space Trust. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- Simpson, Gary D.; Thompson, Stephen C.; Noller, J. Stratton; Lettis, William R. (October 1997). "The Northern San Gregorio Fault Zone: Evidence for the Timing of Late Holocene Earthquakes near Seal Cove, California". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 87 (5): 1158–1170. doi:10.1785/BSSA0870051158. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- Svanevik, Michael; Burgett, Shirley. (2001). San Mateo County Parks: A Remarkable Story of Extraordinary Places and the People who Built Them. San Mateo County Parks and Recreation Foundation. ISBN 1881529673. OCLC 45394273.

- Tokofsky, Peter (August 2, 2023). "Tree removal begins at Pillar Point Bluff". Half Moon Bay Review. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- Tetra Tech, Inc. (January 9, 2012.). "Environmental Assessment and Finding of No Significant Impact For the Low Impact Development Retrofit At Pillar Point Air Force Station, California". Santa Maria, California. Unclassified. Defense Technical Information Center. Accession Number: ADA618729.

- Thomas, John Hunter (1961). Flora of the Santa Cruz Mountains of California: A Manual of the Vascular Plants. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804718622. OCLC 1357629653.

- Weigel, Samantha (March 21, 2015). "POST to connect Coastal Trail: Nonprofit buys 21 acres at Pillar Point bluffs, will donate to count". San Mateo Daily Journal. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- Weigel, Samantha (October 8, 2016). "Pillar Point bluffs preserved in perpetuity: County parks, nonprofit Peninsula Open Space District partner to link coastal trail". San Mateo Daily Journal. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- Washburn, H. A.; Blisniuk, K.; Andersen, D. W. (December 10, 2019). "Tectonic Investigation of the Northern San Gregorio Fault, San Mateo County, California". American Geophysical Union. Fall Meeting 2019. 2019AGUFM.T23F0441W.