Like other pressure relief valves (PRV), pilot-operated relief valves (PORV) are used for emergency relief during overpressure events (e.g., a tank gets too hot and the expanding fluid increases the pressure to dangerous levels). PORV are also called pilot-operated safety valve (POSV), pilot-operated pressure relief valve (POPRV), or pilot-operated safety relief valve (POSRV), depending on the manufacturer and the application. Technically POPRV is the most generic term, but PORV is often used generically (as in this article) even though it should refer to valves in liquid service.

In conventional PRVs, the valve is normally held closed by a spring or similar mechanism that presses a disk or piston on a seat, which is forced open if the pressure is greater than the mechanical value of the spring. In the PORV, the valve is held shut by piping a small amount of the fluid to the rear of the sealing disk, with the pressure balanced on either side. A separate actuator on the piping releases pressure in the line if it crosses a threshold. This releases the pressure on the back of the seal, causing the valve to open.

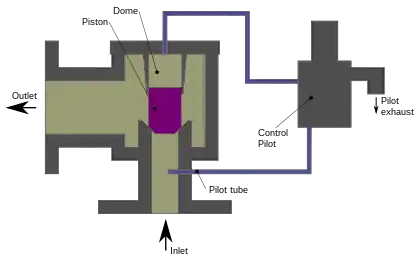

The essential parts of a PORV are a pilot valve (or control pilot), a main valve, a pilot tube, the dome, a disc or piston, and a seat. The volume above the piston is called the dome.[1]

Mode of functioning

The pressure is supplied from the upstream side (the system being protected) to the dome often by a small pilot tube. The downstream side is the pipe or open air where the PORV directs its exhaust. The outlet pipe is typically larger than the inlet. 2 in × 3 in (51 mm × 76 mm), 3 in × 4 in (76 mm × 102 mm), 4 in × 6 in (100 mm × 150 mm), 6 in × 8 in (150 mm × 200 mm), 8 in × 10 in (200 mm × 250 mm) are some common sizes.

The upstream pressure tries to push the piston open but it is opposed by that same pressure because the pressure is routed around to the dome above the piston. The area of the piston on which fluid force is acting is larger in the dome than it is on the upstream side; the result is a larger force on the dome side than the upstream side. This produces a net sealing force.

The pressure from the pilot tube to the dome is routed through the actual control pilot valve. There are many designs but the control pilot is essentially a conventional PRV with the special job of controlling pressure to the main valve dome. The pressure at which the control pilot relieves is the functional set pressure of the PORV. When the pilot valve reaches set pressure it opens and releases the pressure from the dome. The piston is then free to open and the main valve exhausts the system fluid. The control pilot opens either to the main valve exhaust pipe or to atmosphere.

- Snap acting

- At set pressure the valve snaps to full lift. This can be quite violent on large pipes with significant pressure. The pressure has to drop below the set pressure in order for the piston to reseat (see blowdown in relief valve article).

- Modulating

- The pilot is designed to open gradually, so that less of the system fluid is lost during each relief event. The piston lifts in proportion to the overpressure. Blowdown is typically short.

Comparison to conventional pressure relief valves

Advantages

- Smaller package on the larger pipe sizes.

- More options for control.

- Seals more tightly as the system pressure approaches but does not reach set pressure.

- Control pilot can be mounted remotely.

- Some designs allow for changes in orifice size within the main valve.

- Can be used in engines.

- Higher Operating-to-Set Pressure ratio.

Disadvantages

- More complex, resulting in various fail-open failure modes.

- More expensive at smaller sizes (starts to even out as pipe size increases).

- Small parts in pilot valve are sensitive to contaminant particles.

- Soft goods typically installed in pilot valves cannot withstand higher temperature fluids.

See also

References

- ↑ "Pilot-operated relief valve". Retrieved 2012-10-05.