| Pilot whales Temporal range: Pliocene to recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

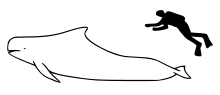

| Size of short-finned pilot whale compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Delphinidae |

| Subfamily: | Globicephalinae |

| Genus: | Globicephala Lesson, 1828 |

| Type species | |

| Delphinus globiceps[1] Cuvier, 1812 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Globicephalus | |

Pilot whales are cetaceans belonging to the genus Globicephala. The two extant species are the long-finned pilot whale (G. melas) and the short-finned pilot whale (G. macrorhynchus). The two are not readily distinguishable at sea, and analysis of the skulls is the best way to distinguish between the species. Between the two species, they range nearly worldwide, with long-finned pilot whales living in colder waters and short-finned pilot whales living in tropical and subtropical waters. Pilot whales are among the largest of the oceanic dolphins, exceeded in size only by the orca. They and other large members of the dolphin family are also known as blackfish.

Pilot whales feed primarily on squid, but will also hunt large demersal fish such as cod and turbot. They are highly social and may remain with their birth pod throughout their lifetime. Short-finned pilot whales are one of the few mammal species in which females go through menopause, and postreproductive females continue to contribute to their pod. Pilot whales are notorious for stranding themselves on beaches, but the reason behind this is not fully understood, although marine biologists have shed light on the discovery it is due to the mammals inner ear (their principal navigational sonar) being damaged from noise-pollution in the ocean, such as from cargo ships or military exercises.[2] The conservation status of short-finned and long-finned pilot whales has been determined to be least concern.

Naming

The animals were named "pilot whales" because pods were believed to be "piloted" by a leader.[3][4] They are also called "pothead whales" and "blackfish". The genus name is a combination of the Latin word globus ("round ball" or "globe") and the Greek word Kephale ("head").[3][4]

Taxonomy and evolution

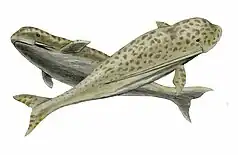

Pilot whales are classified into two species; the long-finned pilot whale (Globicephala melas) and the short-finned pilot whale (G. macrorhynchus). The short-finned pilot whale was described, from skeletal materials only, by John Edward Gray in 1846. He presumed from the skeleton that the whale had a large beak. The long-finned pilot whale was first classified by Thomas Stewart Traill in 1809 as Delphinus melas.[5] Its scientific name was eventually changed to Globicephala melaena. Since 1986, the specific name of the long-finned pilot whale was changed to its original form melas.[6] Other species classifications have been proposed but only two have been accepted.[7] There exist geographic forms of short-finned pilot whales off the east coast of Japan,[8] which comprise genetically isolated stocks.[9]

Fossils of an extinct relative, Globicephala baereckeii, have been found in Pleistocene deposits in Florida.[3] Another Globicephala dolphin was discovered in Pliocene strata in Tuscany, Italy, and was named G. etruriae.[3] Evolution of Tappanaga, the endemic, larger form of short-finned pilots found in northern Japan, with similar characteristics to the whales found along Vancouver Island and northern USA coasts,[10] has indicated that the geniture of this form could be caused by the extinction of long-finned pilots in north Pacific in the 12th century, where Magondou, the smaller, southern type possibly filled the former niches of long-finned pilots, adapting and colonizing into colder waters.[11]

Description

Pilot whales are mostly dark grey, brown, or black, but have some light areas such as a grey saddle patch behind the dorsal fin.[4] Other light areas are an anchor-shaped patch under the chin, a faint blaze marking behind the eye, a large marking on the belly, and a genital patch.[4] The dorsal fin is set forward on the back and sweeps backwards. A pilot whale is more robust than most dolphins and has a distinctive large, bulbous melon.[4] Pilot whales' long, sickle-shaped flippers and tail stocks are flattened from side to side.[4] Male long-finned pilot whales develop more circular melons than females,[4] although this does not seem to be the case for short-finned pilot whales off the Pacific coast of Japan.[12]

Long-finned and short-finned pilot whales are so similar, it is difficult to tell the two species apart.[3] They were traditionally differentiated by the length of the pectoral flippers relative to total body length and the number of teeth.[7] The long-finned pilot whale was thought to have 9–12 teeth in each row and flippers one-fifth of total body length, compared to the short-finned pilot whale with its 7–9 teeth in each row and flippers one-sixth of total body length.[4] Studies of whales in the Atlantic showed much overlap in these characteristics between the species, making them clines instead of distinctive features.[4] Thus, biologists have since used skull differences to distinguish the two species.[3][4]

The size and weight depend on the species, as long-finned pilot whales are generally larger than short-finned pilot whales.[12][13] Their lifespans are about 45 years in males and 60 years in females for both species. Both species exhibit sexual dimorphism. Adult long-finned pilot whales reach a body length of approximately 6.5 m, with males being 1 m longer than females.[14] Their body mass reaches up to 1,300 kg in females and up to 2,300 kg in males.[15] For short-finned pilot whales, adult females reach a body length of about 5.5 m, while males reach 7.2 m and may weigh up to 3,200 kg.[15]

Distribution and habitat

Pilot whales can be found in oceans nearly worldwide, but data about current population sizes is deficient. The long-finned pilot whale prefers slightly cooler waters than the short-finned and is divided into two populations. The smaller group is found in a circumpolar band in the Southern Ocean from about 20 to 65°S. It may be sighted off the coasts of Chile, Argentina, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.[16] An estimated more than 200,000 individuals were in this population in 2006. The second, much larger, population inhabits the North Atlantic Ocean, in a band from South Carolina in the United States across to the Azores and Morocco at its southern edge and from Newfoundland to Greenland, Iceland, and northern Norway at its northern limit. This population was estimated at 778,000 individuals in 1989. It is also present in the western half of the Mediterranean Sea.[16]

The short-finned pilot whale is less populous. It is found in temperate and tropical waters of the Indian, Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.[17] Its population overlaps slightly with the long-finned pilot whale in the temperate waters of the North Atlantic and Southern Oceans.[3] About 150,000 individuals are found in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. More than 30,000 animals are estimated in the western Pacific, off the coast of Japan. Pilot whales are generally nomadic, but some populations stay year-round in places such as Hawaii and parts of California.[3] They prefer the waters of the shelf break and slope.[3] Once commonly seen off of Southern California, short-finned pilot whales disappeared from the area after a strong El Niño year in the early 1980s, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.[18] In October 2014, crew and passengers on several boats spotted a pod of 50–200 off Dana Point, California.[18]

Behavior and life history

Foraging and parasites

Although pilot whales are not known to have many predators, possible threats come from humans and killer whales. Both species eat primarily squid.[19] The whales make seasonal inshore and offshore movements in response to the dispersal of their prey.[3] Fish that are consumed include Atlantic cod, Greenland turbot, Atlantic mackerel, Atlantic herring, hake, and spiny dogfish in the northwest Atlantic.[3] In the Faroe Islands, whales mostly eat squid, but will also eat fish species such as greater argentine and blue whiting. However, Faroe whales do not seem to feed on cod, herring, or mackerel, even when they are abundant.[20]

Pilot whales generally take several breaths before diving for a few minutes. Feeding dives may last over ten minutes. They are capable of diving to depths of 600 meters, but most dives are to a depth of 30–60 m. Shallow dives tend to take place during the day, while deeper ones take place at night. When making deep dives, pilot whales often make fast sprints to catch fast-moving prey such as squid.[21] Compared to sperm whales and beaked whales, foraging short-finned pilot whales are more energetic at the same depth. When they reach the end of their dives, pilot whales will sprint, possibly to catch prey, and then make a few buzzes.[21] This is unusual, considering that deep-diving, breath-holding animals would be expected to swim slowly to conserve oxygen. The animal's high metabolism possibly allows it to sprint at deep depths, which would also give it shorter diving periods than some other marine mammals.[21] This may also be the case for long-finned pilot whales.[22]

Pilot whales are often infested with whale lice, cestodes, and nematodes.[4] They also can be hosts to various pathogenic bacteria and viruses, such as Streptococcus, Pseudomonas, Escherichia, Staphylococcus, and influenza.[4] One sample of Newfoundland pilot whales found that the most common illness was an upper respiratory tract infection.[23]

Social structure

Both species live in groups of 10–30, but some groups may number 100 or more. Data suggest the social structures of pilot whale pods are similar to those of "resident" killer whales. The pods are highly stable and the members have close matrilineal relationships.[3] Pod members are of various age and sex classes, although adult females tend to outnumber adult males. They have been observed making various kin-directed behaviors, such as providing food.[24] Numerous pods will temporarily gather, perhaps to allow individuals from different pods to interact and mate,[4] as well as provide protection.[13]

Both species are loosely polygynous.[13] Data suggest both males and females remain in their mother's pod for life; despite this, inbreeding within a pod does not seem to occur.[4] During aggregations, males will temporarily leave their pods to mate with females from other pods.[25] Male reproductive dominance or competition for mates does not seem to exist.[26] After mating, a male pilot whale usually spends only a few months with a female, and an individual may sire several offspring in the same pod.[27] Males return to their own pods when the aggregations disband, and their presence may contribute to the survival of the other pod members.[25] No evidence of "bachelor" groups has been found.[13][25]

Pilot whale pods off southern California have been observed in three different groups: traveling/hunting groups, feeding groups and loafing groups.[28] In traveling/hunting groups, individuals position themselves in chorus lines stretching two miles long, with only a few whales underneath.[29] Sexual and age-class segregation apparently occurs in these groups.[28] In feeding groups, individuals are very loosely associated, but may move in the same direction.[28] In loafing groups, whales number between 12 and 30 individuals resting. Mating and other behaviors may take place.[28]

Reproduction and lifecycle

Pilot whales have one of the longest birth intervals of the cetaceans,[3] calving once every three to five years. Most matings and calvings occur during the summer for long-finned pilot whales.[30] For short-finned pilot whales of the Southern Hemisphere, births are at their highest in spring and autumn, while in Northern Hemisphere, the time in which calving peaks can vary by population.[30] For long-finned pilot whales, gestation lasts 12–16 months, and short-finned pilot whales have a 15-month gestation period.[3]

The calf nurses for 36–42 months, allowing for extensive mother-calf bonds.[3] Young pilot whales will take milk until as old as 13–15 years of age. Short-finned pilot whale females will go through menopause,[31] but this is not as common in females of long-finned pilot whales.[32] Postreproductive females possibly play important roles in the survival of the young.[24][33] Postreproductive females will continue to lactate and nurse young. Since they can no longer bear young of their own, these females invest in the current young, allowing them to feed even though they are not their own.[3] Short-finned pilot whales grow more slowly than long-finned pilot whales. For the short-finned pilot whale, females become sexually mature at 9 years old and males at about 13–16 years.[3] For the long-finned pilot whale, females reach maturity at around eight years and males at around 12 years.[3]

Vocalizations

Pilot whales emit echolocation clicks for foraging and whistles and burst pulses as social signals (e.g. to keep contact with members of their pod). With active behavior, vocalizations are more complex, while less-active behavior is accompanied by simple vocalizations. Differences have been found in the calls of the two species.[34] Compared with short-finned pilot whales, long-finned pilot whales have relatively low-frequency calls with narrow frequency ranges.[34] In one study of North Atlantic long-finned pilot whales, certain vocalizations were heard to accompany certain behaviors.[35] When resting or "milling", simple whistles are emitted.[35] Surfacing behavior is accompanied by more complex whistles and pulsed sounds.[35] The number of whistles made increases with the number of subgroups and the distance in which the whales are spread apart.[35]

A study of short-finned pilot whales off the southwest coast of Tenerife in the Canary Islands has found the members of a pod maintained contact with each other through call repertoires unique to their pod.[36] A later study found, when foraging at around 800 m deep, short-finned pilot whales make tonal calls.[37] The number and length of the calls seem to decrease with depth despite being farther away from conspecifics at the surface. As such, the surrounding water pressure affects the energy of the calls, but it does not appear to affect the frequency levels.[37]

When in stressful situations, pilot whales produce "shrills" or "plaintive cries", which are variations of their whistles.[38] To elude predators, long-finned pilot whales off the southern coast of Australia have been observed to mimic the calls of orcas while scavenging for food. This behaviour is thought to deter orca pods from approaching the pilot whales.[39]

Antagonistic interactions with other species

Pilot whales have been occasionally observed mobbing or chasing other species of cetaceans. In several parts of the world, including off Iceland, long-finned pilot whales have been frequently documented chasing killer whales.[40] The reasons for these chases are unknown, but it has been proposed that they might be due to either competition for prey or an anti-predation strategy. In 2021 an adult female killer whale with a newborn pilot whale travelling alongside her was observed off Western Iceland, leading scientists to question whether the relationship between these species might be far more complex than previously suggested.[41] It is not known whether the newborn was adopted or abducted, but this same female killer whale was seen a year later interacting with a larger group of pilot whales.

Stranding

Of the cetaceans, pilot whales are among the most common stranders.[42] Because of their strong social bonds, whole groups of pilot whales will strand. Single stranders have been recorded and these are usually diseased.[3] Group stranding tends to be of mostly healthy individuals. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain group strandings.[3] When using magnetic fields for navigation, the whales have been suggested to get perplexed by geomagnetic anomalies or they may be following a sick member of their group that got stranded.[3] The pod also may be following a member of high importance that got stranded and a secondary social response makes them keep returning.[4] Researchers from New Zealand have successfully used secondary social responses to keep a stranding pod of long-finned pilot whales from returning to the beach.[43] In addition, the young members of the pod were taken offshore to buoys, and their distress calls lured the older whales back out to sea.[43]

In September 2022, nearly 200 pilot whales died after becoming stranded on Ocean Beach, part of Tasmania's west coast. Authorities said only about 35 survived of the 230 that were stranded.[44]

Human interaction

The IUCN lists long-finned pilot whales as "least concern" in the Red List of Threatened Species. Long-finned pilot whales in the North and Baltic Seas are listed in Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). Those from northwest and northeast Atlantic may also need to be included to Appendix II of CMS.[16] The short-finned pilot whale is listed on Appendix II of CITES.[17]

Hunting

The long-finned pilot whale has traditionally been hunted by "driving", which involves many hunters and boats gathering in a semicircle behind a pod of whales close to shore, and slowly driving them towards a bay, where they become stranded and are then slaughtered. This practice was common in both the 19th and 20th centuries. The whales were hunted for bone, meat, oil, and fertilizer. In the Faroe Islands, pilot whale hunting started at least in the 16th century,[4] and continued into modern times, with thousands being killed during the 1970s and 1980s.[45][46] In other parts of the North Atlantic, such as Norway, West Greenland, Ireland and Cape Cod, pilot whales have also been hunted, but to a lesser extent.[47][48] One fishery at Cape Cod harvested 2,000–3,000 whales per year during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[49] Newfoundland's long-finned pilot whale fishery was at its highest in 1956, but declined shortly after[45] and is now defunct. In the Southern Hemisphere, exploitation of long-finned pilot whales has been sporadic and low.[45] Currently, long-finned pilot whales are only hunted at the Faroe Islands and Greenland.[16]

According to the IUCN the harvesting of this species for food in the Faroe Islands and Greenland has not resulted in any detectable declines in abundance.[50]

The short-finned pilot whale has also been hunted for many centuries, particularly by Japanese whalers. Between 1948 and 1980, hundreds of whales were exploited at Hokkaido and Sanriku in the north and Taiji, Izu, and Okinawa in the south.[13] These fisheries were at their highest in the late 1940s and early 1950s;[13] 2,326 short-finned pilot whales were harvested in the mid- to late 1980s.[17] This had decreased to about 400 per year by the 1990s.

Pilot whales have also fallen victim to bycatches. In one year, around 30 short-finned pilot whales were caught by the squid round-haul fishery in southern California.[51] Likewise, California's drift gill net fishery took around 20 whales a year in the mid-1990s.[4] In 1988, 141 whales caught on the east coast of the U.S. were taken by the foreign Atlantic mackerel fishery, which forced it to be shut down.[4]

Pollution

As with other marine mammals, pilot whales are susceptible to certain pollutants. Off the Faroes, France, the UK, and the eastern US, pilot whales were found to have been contaminated with high amounts of DDT and PCB.[4] Pollutants such as DDT and mercury can be passed from mothers to their babies during gestation and lactation.[52] The Faroes whales have also been contaminated with cadmium and mercury.[53] However, pilot whales from Newfoundland and Tasmania were found to have had very low levels of DDT.[4] Short-finned pilot whales off the west coast of the US have had high amounts of DDT and PCB in contrast to the low amounts found in whales from Japan and the Antilles.[4]

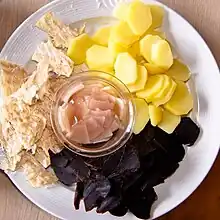

Cuisine

Pilot whale meat is available for consumption in very few areas of Japan, mainly along the central Pacific coast, and also in other areas of the world, such as the Faroe Islands. The meat is high in protein (higher than beef) and low in fat.[54] Because a whale's fat is contained in the layer of blubber beneath the skin, and the muscle is high in myoglobin, the meat is a dark shade of red.[54][55] In Japan, where pilot whale meat can be found in certain restaurants and izakayas, the meat is sometimes served raw, as sashimi, but just as often pilot whale steaks are marinated, cut into small chunks, and grilled.[55] When grilled, the meat is slightly flaky and quite flavorful, somewhat gamey, though similar to a quality cut of beef, with distinct yet subtle undertones recalling its marine origin.[54][55][56]

In both Japan and the Faroe Islands, the meat is contaminated with mercury and cadmium, causing a health risk for those who frequently eat it, especially children and pregnant women.[57] In November 2008, an article in New Scientist reported that research done on the Faroe Islands resulted in two chief medical officers recommending against the consumption of pilot whale meat, considering it to be too toxic.[58] In 2008, the local authorities recommended that pilot whale meat should no longer be eaten due to the contamination. This has resulted in reduced consumption, according to a senior Faroese health official.[59]

Captivity

.jpg.webp)

Pilot whales, mostly short-finned pilot whales, have been kept in captivity in various marine parks, arguably starting in the late 1940s.[60] Since 1973, some long-finned pilot whales from New England waters were taken and temporarily kept in captivity.[61] Short-finned pilot whales off southern California, Hawaii and Japan have been kept in aquariums and oceanariums. Several pilot whales from southern California and Hawaii were taken into captivity during the 1960s and early 1970s,[61][62] two of which were placed at SeaWorld San Diego. During the 1970s and early 1980s, six pilot whales were captured alive by drive hunts and taken for public display.[4]

Pilot whales have historically had low survival rates in captivity, with the average annual survival being 0.51 years during the mid-1960s to early 1970s.[62] There have been a few exceptions to the rule. Bubbles, a female short-finned pilot whale, who was displayed in Marineland of the Pacific and eventually at Sea World California, lived to be somewhere in her 50s when she eventually died on 12 June 2016.[63] In 1968, a pilot whale was captured, given the name Morgan, and trained by the U.S. Navy's Deep Ops to retrieve deeper-attached objects from the ocean floor. He dove a record depth of 1654 feet and was used for training until 1971.[64]

Films

There are two documentaries entirely dedicated to the pilot whales.

- Full-length Cheetahs of the deep (49’, 2014, directed by Rafa Herrero Massieu[65]) — tells about the way of life, features of social interaction, the subtleties of hunting, games and breeding on the example of a group of non-migrating short-finned pilot whales living between the Islands of Tenerife and La Gomera of the Canary archipelago. A curious feature of the film is that: “all marine mammals filmed in freediving”.

- Short film My Pilot, Whale (28’, 2014, directed by Alexander and Nicole Gratovsky[66]) demonstrates the possibility of interaction between humans and free-living pilot whales, offering the viewer a number of philosophical questions related to cetaceans: about their attitude to the world, what we have in common, what we — humans — can learn from them, and so on. The film has received a number awards of international film festivals.[67][68]

See also

References

- ↑ Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ "Sonic Sea". Brown Media Archives and Peabody Awards Collection, University of Georgia.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Olson, P.A. (2008) "Pilot whale Globicephala melas and G. muerorhynchus" pp. 847–52 in Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, Perrin, W. F., Wursig, B., and Thewissen, J. G. M. (eds.), Academic Press; 2nd edition, ISBN 0-12-551340-2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Ridgway, S. H. (1998). Handbook of Marine Mammals: The second book of dolphins and the porpoises, Volume 6, Elsevier. pp. 245–69. ISBN 0-12-588506-7

- ↑ Traill T. S. (1809). "Description of a new species of whale, Delphinus melas". In a letter from Thomas Stewart Traill, M.D. to Mr. Nicholson". Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry, and the Arts. 1809: 81–83.

- ↑ Starting, Jones Jr; Carter, D.C.; Genoways, H.H.; Hoffman, R.S.; Rice, D.W.; Jones (1986). "Revised checklist of North American mammals north of Mexico". Occ Papers Mus Texas Tech Univ. 107: 5.

- 1 2 van Bree, P.J.H. (1971). "On Globicephala seiboldi, Gray 1846, and other species of pilot whales. (Notes on cetacean, Delphinoidea III)". Beaufortia. 19: 79–87.

- ↑ Kasuya, T., Sergeant, D. E., Tanaka, K. (1986). "Segregation of two forms of short-finned pilot whales off the Pacific coast of Japan" (PDF). Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute. 39: 77–90.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Wada, S. (1988). "Genetic differentiation between two forms of short-finned pilot whales off the Pacific coast of Japan" (PDF). Sci Rep Whales Res Inst. 39: 91–101.

- ↑ Hidaka T. Kasuya T. Izawa K. Kawamichi T. 1996. The encyclopaedia of animals in Japan (2) - Mammals 2. ISBN 9784582545524 (9784582545517) (4582545521). Heibonsha

- ↑ Amano M. (2012). "みちのくの海のイルカたち(特集 みちのくの海と水族館の海棲哺乳類)" (PDF). Isana 56. Faculty of Fisheries of University of Nagasaki, Isanakai: 60–65. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- 1 2 Yonekura, M., Matsui, S. & Kasuya, T. (1980). "On the external characters of Globicephala macrorhynchus off Taiji, Pacific coast of Japan". Sci. Rep. Inst. 32: 67–95. ISSN 0083-9086.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kasuya, T., Marsh, H. (1984). "Life history and reproductive biology of the short-finned pilot whale, Globicephala macrorhynchus, off the Pacific Coast Japan" (PDF). Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 6: 259–310. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Bloch D, Lockyer C, Zachariassen M (1993). "Age and growth parameters of the long-finned pilot whale off the Faroe Islands". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 14: 163–208.

- 1 2 Jefferson, T. A, Webber, M. A., Pitman, R. L., (2008) Marine mammals of the world. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- 1 2 3 4 Minton, G.; Reeves, R.; Braulik, G. (2018). "Globicephala melas". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T9250A50356171. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T9250A50356171.en. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- 1 2 3 Minton, G.; Braulik, G.; Reeves, R. (2018). "Globicephala macrorhynchus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T9249A50355227. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T9249A50355227.en. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- 1 2 "Whale Watchers Unexpectedly Sight Rare Pilot Whales".

- ↑ Randall R. Reeves; Brent S. Stewart; Phillip J. Clapham; James A. Powell (2002). National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 0-375-41141-0.

- ↑ Desportes, G., Mouritsen, R. (1993) "Preliminary results on the diet of long-finned pilot whales off the Faroe Islands". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. (special issue 14): 305–24.

- 1 2 3 Aguilar de Soto, N.; Johnson, M. P.; Madsen, P. T.; Díaz, F.; Domínguez, I.; Brito, A.; Tyack, P. (2008). "Cheetahs of the deep sea: deep foraging sprints in short-finned pilot whales off Tenerife (Canary Islands)" (PDF). Journal of Animal Ecology. 77 (5): 936–47. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01393.x. PMID 18444999.

- ↑ Heide-Jørgensen M.P., Bloch, D., Stefansson, E., Mikkelsen, B., Ofstad, L. H., Dietz, R. (2002). "Diving behaviour of long-finned pilot whales Globicephala melas around the Faroe Islands". Wildlife Biology. 8 (4): 307–13. doi:10.2981/wlb.2002.020. S2CID 131994947.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Cowan, Daniel F. (1966). "Observations on the pilot whale Globicephala melaena: Organweight and growth". The Anatomical Record. 155 (4): 623–628. doi:10.1002/ar.1091550413. S2CID 82948550.

- 1 2 Pryor, K., Norris K. S, Marsh, H., Kasuya, T. (1991) "Changes in the role of a female pilot whale with age", pp. 281–86 in Dolphin societies, Pryor, K., Norris K. S. (eds), Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- 1 2 3 Amos, B; Schlötterer, C; Tautz, D (1993). "Social structure of pilot whales revealed by analytical DNA profiling". Science. 260 (5108): 670–2. Bibcode:1993Sci...260..670A. doi:10.1126/science.8480176. PMID 8480176.

- ↑ Donovan, G. P., Lockyer, C. H., Martin, A. R., (1993) "Biology of Northern Hemisphere Pilot Whales", International Whaling Commission Special Issue 14. ISBN 9780906975275

- ↑ Amos, B; Barrett, J; Dover, GA (1991). "Breeding behaviour of pilot whales revealed by DNA fingerprinting". Heredity. 67 (1): 49–55. doi:10.1038/hdy.1991.64. PMID 1917551.

- 1 2 3 4 Norris, K. S., Prescott, J. H. (1961). "Observations on Pacific cetaceans of Californian and Mexican waters". University of California Publications in Zoology. 63: 291–402. OL 5870789M.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Leatherwood, S., Lingle, G. E., Evans, W. E., (1973) "The Pacific pilot whale, Globicephala spp". Naval Undersea Center Technical Note 933.

- 1 2 Jefferson T. A., Leatherwood, S., Webber, M. A. (1993) "FAO Species identification guide. Marine mammals of the world". UNEP/FAO, Rome. Preview Archived 2 March 2013 at Archive-It

- ↑ Marsh, H., Kasuya T. (1984). "Ovarian changes in the short-finned pilot whale, Globicephala macrorhynchus Archived 17 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine" Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 6: 311–35. Special Issue.

- ↑ Martin A.R, Rothery P. (1993). "Reproductive parameters of female long-finned pilot whales (Globicephala melas) around the Faroe Islands" Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 14 263–304. Special Issue.

- ↑ Foote, A. D. (2008). "Mortality rate acceleration and post-reproductive lifespan in matrilineal whale species". Biol. Lett. 4 (2): 189–91. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0006. PMC 2429943. PMID 18252662.

- 1 2 Rendell, L. E.; Matthews, J. N.; Gill, A.; Gordon, J. C. D.; MacDonald, D. W. (1999). "Quantitative analysis of tonal calls from five odontocete species, examining interspecific and intraspecific variation". Journal of Zoology. 249 (4): 403–410. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1999.tb01209.x.

- 1 2 3 4 Weilgart, Lindas.; Whitehead, Hal (1990). "Vocalizations of the North Atlantic pilot whale (Globicephala melas) as related to behavioral contexts". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 26 (6). doi:10.1007/BF00170896. S2CID 34187605.

- ↑ Scheer, M., Hofmann, B., Behr, I.P. (1998) "Discrete pod-specific call repertoires among short-finned pilot whales (Globicephala macrorhynchus) off the SW coast of Tenerife, Canary Islands". Abstract World Marine Mammal Science Conference, 20–24. January, Monaco by European Cetacean Society and Society for Marine Mammalogy.

- 1 2 Jensen, F. H.; Perez, J. M.; Johnson, M.; Soto, N. A.; Madsen, P. T. (2011). "Calling under pressure: short-finned pilot whales make social calls during deep foraging dives". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1721): 3017–3025. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.2604. PMC 3158928. PMID 21345867.

- ↑ Alagarswami, K., Bensam, P., Rajapandian, M. E., Fernando, A. B. (1973). "Mass stranding of Pilot whales in the Gulf of Mannar". Indian J. Fish. 20 (2): 269–279.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Leckie, Evelyn (14 December 2020). "Pilot whales recorded along Great Australian Bight found to be mimicking predators' calls". ABC News. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ↑ Selbmann A.; Basran C.J.; Bertulli C.G.; Hudson T.; Mrusczok M.; Rasmussen M.H.; Rempel J.N.; Scott J.; Svavarsson J.; Weensveen, P.J; Whittaker M. (2022). "Occurrence of long-finned pilot whales (Globicephala melas) and killer whales (Orcinus orca) in Icelandic coastal waters and their interspecific interactions". Acta Ethologica. 25 (3): 141–154. doi:10.1139/z03-127. S2CID 56260446.

- ↑ Mrusczok M.; Zwamborn E.; von Schmalensee M.; Rodriguez Ramallo S.; Stefansson R. A. (2023). "First account of apparent alloparental care of a long-finned pilot whale calf (Globicephala melas) by a female killer whale (Orcinus orca)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. doi:10.1139/cjz-2022-0161. S2CID 257010608.

- ↑ "Pilot whale". iwc.int. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- 1 2 Dawson, S. M., S. Whitehouse, M. Williscroft (1985). "A mass stranding of pilot whales in Tryphena Harbour, Great Barrier Island". Invest. Cetacea. 17: 165–73.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Nearly 200 stranded pilot whales die on Tasmanian beach but dozens saved and returned to sea". the Guardian. 22 September 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- 1 2 3 Mitchell, E. D. (1975). "Porpoise, dolphin, and small whale fisheries of the world: status and problems". International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. 3: 1–129.

- ↑ Hoydal, K. (1987). "Data on the long-finned pilot whale (Globicephala melaena Traill), in Faroe waters and an attempt to use the 274 years time series of catches to assess the state of the stock". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 37: 1–27.

- ↑ Kapel, F.O. (1975). "Preliminary notes on the occurrence and exploitation of smaller Cetacea in Greenland". J. Fish. Res. Board Can. 32 (7): 1079–82. doi:10.1139/f75-128.

- ↑ O'Riordan, C. E. (1975). "Long-finned pilot whales, Globicephala, driven ashore in Ireland, 1800–1973". J. Fish. Res. Board Can. 32 (7): 1101–03. doi:10.1139/f75-131.

- ↑ Mitchell, E. D. (1975). "Report of the meeting on smaller cetaceans, Montreal, 1–11 April 1974". J. Fish. Res. Board Can. 32 (7): 889–983. doi:10.1139/f75-117.

- ↑ "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ↑ Miller, D. J., Herder, M. J., Scholl, J. P. (1983) "California marine mammal- fishery interaction study. 1979–81", NMFS Southwest Fish. Cent., Admin. Rep. No. LJ-83-13C

- ↑ Dam, Maria; Bloch, Dorete (December 2000). "Screening of Mercury and Persistent Organochlorine Pollutants in Long-Finned Pilot Whale (Globicephala melas) in the Faroe Islands". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 40 (12): 1090–1099. doi:10.1016/S0025-326X(00)00060-6.

- ↑ Simmonds, MP; Johnston, PA; French, MC; Reeve, R; Hutchinson, JD (1994). "Organochlorines and mercury in pilot whale blubber consumed by Faroe islanders". The Science of the Total Environment. 149 (1–2): 97–111. Bibcode:1994ScTEn.149...97S. doi:10.1016/0048-9697(94)90008-6. PMID 8029711.

- 1 2 3 Browne, Anthony (9 September 2001). "Stop Blubbering: Whales are supposed to be protected but that doesn't stop the Japanese killing and eating hundreds of them every year. But does the West's moral outrage over the pursuit of our gentle leviathans amount to anything more than hypocrisy and cultural bullying?". The Observer. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 "No matter how you slice it, whale tastes unique". Planet Ark. Reuters. 2002. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ↑ Buncombe, Andrew (2005). "The Whaling Debate: Arctic Lament". Ezilon. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ↑ Haslam, Nick (14 September 2003) Faroes' controversial whale hunt, BBC.

- ↑ MacKenzie, Debora (28 November 2008) Faroe Islanders told to stop eating 'toxic' whales, New Scientist.

- ↑ Pilot Whale Meat On The Way Out Of Faroese Food Culture, wdcs.org (9 July 2009).

- ↑ Kritzler, H. (1952). "Observations on the pilot whale in captivity". Journal of Mammalogy. 33 (3): 321–334. doi:10.2307/1375770. JSTOR 1375770.

- 1 2 Reeves, R., Leatherwood, S. (1984). "Live-Capture Fisheries for Cetaceans in U. S. and Canadian Waters, 1973–1982". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 34: 497–507.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Walker, W. A. (1975). "Review of the live-capture fishery for smaller cetaceans taken in southern California waters for public display, 1966–73". J. Fish. Res. Board Can. 32 (7): 1197–1211. doi:10.1139/f75-139.

- ↑ McKirdy, Euan; Marco, Tony (12 June 2016). "Bubbles, SeaWorld's oldest pilot whale, dies". CNN. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ Bowers, Clark A.; Henderson, Richard S. (1972). Project Deep Ops: Deep Object Recovery with Pilot and Killer Whales.

- ↑ "Rafa Herrero Massieu profile at IMDb". IMDb. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ↑ ""My Pilot, Whale" film's profile on IMDb". IMDb. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ↑ "Platinum Remi award in the "Oceanography" category of the 49th International Houston Film Festival" (PDF). 1 May 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ↑ Awareness Film Festival, Los Angeles. "Winner in the nomination "Merit Award of Awareness"". Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

External links

- Pilot Whales.org

- Voices in the Sea Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine