| Pioneer Building | |

|---|---|

| |

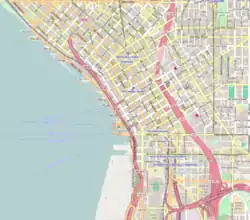

Location within downtown Seattle | |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in Seattle and Washington state from 1892 to 1904[I] | |

| Surpassed by | Alaska Building |

| General information | |

| Type | Commercial offices |

| Location | 600 1st Avenue Pioneer Square, Seattle, Washington 98104 |

| Coordinates | 47°36′08″N 122°20′01″W / 47.60222°N 122.33361°W |

| Construction started | 1889 |

| Completed | 1892 |

| Cost | US$250,000 |

| Owner | Novel Coworking |

| Management | Novel Coworking |

| Height | |

| Roof | 28.04 m (92.0 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 6 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Elmer H. Fisher James Wehn |

Pioneer Building, Pergola, and Totem Pole | |

| Architectural style | Romanesque Revival: Richardsonian Romanesque |

| Part of | Pioneer Square–Skid Road District (ID70000086) |

| NRHP reference No. | 77001340 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 5, 1977 |

| Designated NHL | May 5, 1977 |

| Designated CP | June 22, 1970 |

| References | |

| [1][2][3][4] | |

The Pioneer Building is a Richardsonian Romanesque stone, red brick, terra cotta, and cast iron building located on the northeast corner of First Avenue and James Street, in Seattle's Pioneer Square District. Completed in 1892, the Pioneer Building was designed by architect Elmer Fisher, who designed several of the historic district's new buildings following the Great Seattle Fire of 1889.

Location

From Seattle's earliest days until the early 1880s, the corner of First and James was the site of Henry and Sarah Yesler's home and orchard, with his steam-powered sawmill located across the way. His home served as the center of social life and hospitality in early Seattle. As the city's business district began to grow rapidly in the early 1880s, Yesler moved to his new mansion, designed by architect William E. Boone, three blocks away at 4th and James in 1884. Rather than demolishing his old house and fully redeveloping his property, he moved the house to the back of the lot and filled his First Avenue frontage with displaced buildings purchased and relocated from across the street.

He began planning an office block at First and James in late 1888 with the completed elevation drawings by architects Fisher & Clark put on public display that December. Local media proclaimed it would be one of the finest buildings in the country, and the largest north of San Francisco.[5]

While the lumber was being cut and contracts for the steel work and terra cotta were still being secured, excavation for the southern half of the building began in mid-February, 1889 with the temporary relocation of several existing structures on the site, followed by their demolition, including the original Yesler home, the following month.[6] Yesler's plan was to construct the southern half of the building first, then finish the northern portion the following building season after payments for recently sold property would be secured.[7] Grading was completed and construction began in May but was soon halted due to a shortage of rough stone that was plaguing the city; only 144 tons of the 800 tons of stone that were ordered for the building could be delivered.[8] Several months after the Great Seattle Fire leveled 32 blocks of downtown and new grades and street widths had been firmly established, Yesler proceeded with the construction of the Pioneer Building.

Design

The Pioneer Building is a 94-foot-tall (29 m) symmetrical block, measuring 115 by 111 ft (35 by 34 m).[9] The exterior walls are constructed of Bellingham Bay gray sandstone at the basement and first floor, with red brick on the upper five floors (with the exception of two stone pilasters which extended to the full height of the tower over the main entrance). Spandrel panels and other ornamental elements are terra cotta from Gladding, McBean in California. There are three projecting bays of cast iron, the curved bays at the corner and on the James Street façade, and the angled bay above the main entrance.

The building reflects a mix of Victorian and Romanesque Revival[10] influences. The facades, with vertical pilasters and horizontal belt courses creating a grid, reflect Victorian compositional strategies. Details such as the round arches over groups of windows and the arched main entrance and corner entrance are Romanesque Revival elements.

The exterior walls are load-bearing, as is the firewall that extends through the building from the street to the alley. The interior structure is cast iron columns and steel beams supporting timber joists. As was typical practice in the period, the office floors were designed and built with permanent partitions forming 185 office rooms—a tenant would simply rent one or more office rooms. Light is provided to the interior through two atria—one in the center of the south portion of the building, the other in the north portion of the building.

Constructed at a cost of $270,000,[9] the Pioneer Building was considered one of Seattle's finest post-fire business blocks. It has always been highly visible, forming a portion of one side of Seattle's Pioneer Place Park.

The Pioneer Building originally had a seventh floor tower room (with a pyramidal roof) located directly above the front entrance making the building 110 ft (34 m). It was removed as a result of damage caused by the 1949 earthquake.

History

The newly constructed building quickly became an important business location for downtown Seattle. During the Klondike Gold Rush in 1897, there were 48 different mining companies that had offices in it. During Prohibition, the Pioneer Building was the clandestine location of "Seattle's First Speakeasy."

The downtown area began to grow northward, prompting businesses to move in the same direction. By the 1950s and '60s, the entire Pioneer Square district had fallen upon hard times. Many of the buildings, which were barely 60 years old, sat empty and decaying, and were slated to be torn down and replaced with parking garages. The Seattle Hotel was the first to be razed, which prompted the citizens to initiate a campaign to preserve the district. The rest of the buildings were spared the wrecking ball, and Pioneer Square–Skid Road Historic District were listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[3]

In 1971, the National Park Service proposed a purchase of the Pioneer Building to house the Seattle unit of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. The deal fell through as it was instead purchased by private entrepreneurs and eventually underwent renovations.[11] In 1977, the Pioneer Building was listed as a National Historic Landmark alongside two other elements of the city's post-fire rebuilding: a pergola that was built as a cable car waiting area in 1909 (Pioneer Square pergola), and the 1940 replica of a stolen Tlingit totem pole gifted to the city in 1899 (Pioneer Square totem pole).[4][12]

Today, the Pioneer Building houses, among other things, Doc Maynard's Nightclub and Lounge, where one can buy tickets for the popular Seattle Underground Tour. At the end of the tour, there is a gift shop, located fittingly in the building's ground-floor level.

Several businesses and offices are also located inside, including The Olmsted Law Group PLLC, DePonce Immigration and Citizenship Law, Cost of Wisconsin miniature golf-course designers' Western Regional Office, and Henry's Bail Bonds.

Current use

In December 2015, the Pioneer Building was purchased by workspace provider Novel Coworking, which has renovated the building's interior to create private offices and co-working space for small businesses.[13]

The Pioneer Building is seen here beyond the totem pole that shares its listing in the NRHP.

The Pioneer Building is seen here beyond the totem pole that shares its listing in the NRHP. First Avenue looking north from James Street in 1916 with the Pioneer Square pergola and totem pole bordered by the Pioneer Building (far right) and Mutual Life Building (far left).

First Avenue looking north from James Street in 1916 with the Pioneer Square pergola and totem pole bordered by the Pioneer Building (far right) and Mutual Life Building (far left). Pioneer Building, 2007. Also shown are the Lowman Building, Lowman and Hanford Building, and Smith Tower

Pioneer Building, 2007. Also shown are the Lowman Building, Lowman and Hanford Building, and Smith Tower Although the original tower is gone, the rest of the building's elaborate ornamentation remains intact.

Although the original tower is gone, the rest of the building's elaborate ornamentation remains intact. On the south (Yesler Way) side of the building

On the south (Yesler Way) side of the building

References

- ↑ "Emporis building ID 219384". Emporis. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Pioneer Building". SkyscraperPage.

- 1 2 "Pioneer Building, Pergola, and Totem Pole". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- 1 2 "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ↑ "Yesler's Six-Story Block". The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Library of Congress. December 4, 1888. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- ↑ "Building Season Begins - Preparation for the New Yesler Block-Large Building on Front Street". The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Library of Congress. January 11, 1889. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- ↑ "The Largest for the Year - Hon. H.L. Yesler Sells Two Business Lots for $85,000". The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Library of Congress. February 17, 1889. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- ↑ "A Local Granite Deposit". The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Library of Congress. May 14, 1889. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- 1 2 "Two Years After: What has been accomplished since the great fire". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. No. June 6, 1891. Seattle-Post Intelligencer. Seattle-Post Intelligencer. June 6, 1891. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ↑ "Romanesque Revival". Architectural Styles of America and Europe. October 17, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ↑ Norris, Frank B. (1996). "Chapter 11: Establishing the Seattle Unit". Legacy of the Gold Rush: An Administrative History of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. National Park Service. OCLC 35984297. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- ↑ "NHL nomination for Pioneer Building, Pergola, and Totem Pole". National Park Service. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- ↑ Lerman, Rachel (December 23, 2015), "Seattle’s latest co-working space will be historic Pioneer Building," The Seattle Times

Further reading

- Andrews, Mildred Tanner, editor, Pioneer Square: Seattle's Oldest Neighborhood, University of Washington Press, Seattle and London 2005.

- Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl, and Andersen, Dennis Alan, "After the Fire: The Influence of H. H. Richardson on the Rebuilding of Seattle, 1889-1894," Columbia 17 (Spring 2003), pages 7–15.

- Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl, and Andersen, Dennis Alan, Distant Corner: Seattle Architects and the Legacy of H.H.Richardson, University of Washington Press, Seattle and London 2003.

- Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl, and Andersen, Dennis Alan, "Meeting the Danger of Fire: Design and Construction in Seattle after 1889." Pacific Northwest Quarterly 93 (Summer 2002), pages 115-126.

- Speidel, William C. (1967). Sons of the Profits (There's no business like grow business: the Seattle story, 1851-1901). Seattle: Nettle Creek Publishing Company. pp. 78. ISBN 0-914890-00-X. (hardcover; ISBN 0-914890-06-9 paperback)

Speidel provides a substantial bibliography with extensive primary sources.